This series of articles considers the construction of gender roles and the consequences this has upon our society, including the existence of rape culture. The relationship of gender to the state is then considered, as are the implications for struggle. From Polite Ire.

Gender, power, and struggle

Gender inequality and gender differences

Polite Ire critiques gender essentialism and fashionable brain imaging studies.

The supposed ‘fundamental’ differences between sexes have historically been used as an argument against equal rights, notably in the opposition to women's suffrage. In the early 20th century this opposition was supported by the science of phrenology, later discredited and its conclusions found to be spurious and based upon prejudice. More recently Neuro-scientific researchers have claimed that essential differences between the male and female brain have been uncovered, ‘evidenced’ by neuro-imaging that suggests differing brain structures. However this research is not as clear cut as it may first appear; no participant of a study can be isolated from the affects of socialisation, and as such each supposed ‘essential’ difference may in fact be a result of socialisation (Fine 3-26). There has also been no conclusive evidence found; the methodology is often flawed, the samples small, and the imaging yet to be properly understood. The widely held belief that male and female brains function in different ways is based upon the conclusions of a small minority of studies, conclusions that are damningly dismissed by meta-analyses. The neuro-imaging “evidence” of differently gendered brains may then, in the future, be shown to be similarly laden with prejudice, skewed by societal expectations, as was the case with phrenology. (Fine 131-154)

Where socio-biologists have relied upon the notion of a universal, innate, human nature, a nature that includes gender divisions, they have faced criticism for the inability for this “universal” to be universally applied; for example, while all human societies include a division of labour by sex, these divisions are varied, the social structures changing the form, rigidity and cultural meaning of such divisions (Fausto-Sterling 198-99). This section will consider how gender is socially constructed, and what effect this has upon how the experiences of men and women.

Our society is patriarchal. Our institutions, our traditions, our everyday lives, are filled with examples of men in positions of authority over women. You are born and take your father’s surname. You marry, and tradition holds that a father gives away his daughter to become the wife of a man whose name she shall adopt. Until very recently (and as is often still the case) it is the man in a relationship who holds financial control, and the woman who takes the (unpaid) responsibility for the home and the children. When a woman goes out to work she earns, on average, substantially less than her equivalent male colleagues (despite legislation banning this), is less likely to receive a promotion, and is likely to receive a smaller pension. If a woman is a wife and/or mother, she will also, on average, continue to take responsibility for the home and the family in addition to her paid employment (the infamous ‘second shift’). The decisions made on our behalf by representatives in unions, councils, and governments are made predominantly by men. Despite the now higher proportion of female law graduates to their male counterparts, our legal system remains dominated by men. Equality legislation has not resulted in equality. Why should this be the case?

Cordelia Fine, in her book Delusions of Gender, argues that associational learning is key to our socialisation, a process that includes the internalisation of gender roles and can account for the apparent differences between men and women. Beginning at infancy, our young malleable brains are subjected to pressures to conform to gender norms deemed appropriate for our sex. Thus, to take the obvious examples, girls are surrounded by pink and boys with blue; girls are given toys that will allow them to imitate the life of a traditional wife and mother (e.g. dolls and play-kitchens), and boys that of a traditional working man (tools, building blocks, etc). While in recent years many parents will attempt to reject these for more “gender-neutral” parenting, society as a whole will ensure that a child will soon become aware of what is “normal” for a girl and how that differs from what is “normal” for a boy. Violation of these norms has violent consequences in bullying, harassment, depression and suicide, as demonstrated by this speech given by Texan politician, Joel Burns:

[youtube]ax96cghOnY4[/youtube]

Our associations also affect how we interact with children of different genders, and thus how they are socialised into conforming to gender roles. Crucially, this process is ‘pre-cognitive’, i.e. independent of our opinions or rational judgement. Male babies are talked to, held, and comforted less than female babies. An adult who believes a child to be a boy will judge it to more independent and active than if the adult believes the same child to be a girl. This raises the issue of gender binaries. If I were to describe two people, one as “ambitious, sporting, and competitive” and another as “empathetic, communicative and caring” it is obvious which gender you would automatically assign to each description. And yet we are all aware that people are far more complicated and contradictory than such binaries would allow. These implicit associations of behaviours and personality traits, divided along gendered lines, give us an underlying social reason for our unequal society, as will now be explored. However as will also be seen, change is not as simple as rejecting these associations.

Research has shown that without the awareness, intention or control of an individual, the perception of a connection between subjects and behaviours are reinforced by their repetition. This is not simply a matter of affecting opinion but of having a real effect upon behaviours and ability. For example, research has shown that when gender is made salient, people perform according to the stereotypical ability of their gender (e.g. women less capable at maths, men less capable at empathy) – however when gender is not mentioned there is no such correlation in performance. The subconscious nature of this compliance to a norm demonstrates that while individuals may consciously reject gender roles, their subconscious continues to unknowingly make gendered associations and behave in gender ‘appropriate’ ways. (Fine 3-26)

These associations, implicit in our society, have deep implications when it comes to gender equality. Though discrimination according to gender is not permitted legally, in reality it is much harder to avoid. Research has demonstrated that when equally qualified men and women apply for identical jobs, the gender associations of the vacancy is a key factor in determining who will be successful: women therefore are at a disadvantage in many areas of employment from the outset, as the attributes of a successful worker are typically seen as masculine (ambitious, competitive, independent, dominant etc) – while a woman may be perfectly suited to the role in question, her talents are far less likely to be recognised than they would be in a man. (Fine 27-66) Such discrimination does not seem to affect men when the situation is reversed; men who work in traditionally female jobs (nursing, teaching etc) are more likely to be favoured for promotion, the societal association of men in positions of authority clearing the path for them to progress in their field. The pervasive nature of these associations is apparent from a young age:

Where eleven- to twelve-year-old children are shown pictures of men and women performing unfamiliar jobs, they rate as more difficult, better paid and more important those occupations that happen to be performed by men. (p 66)

Therefore the expectation implicit in liberal feminist theory – that equal access to education and employment based upon merit will lead to gender equality – is inherently flawed, as it does not account for the failure of legislation that has, in theory, permitted women to achieve the same status as men. Socialisation trumps legislation. (Sometimes the facade of equality falls away even in this, as David Cameron’s suggestion that there should be more women on boards of directors because they ‘cost less’ serves to demonstrate).

It is important to recognise that the affects of a patriarchal society are not limited to women, but to people as a whole, distorting the complex and malleable nature of individuals and presenting them as binary and definitive. While it may be difficult for a woman to gain acceptance in a high-status professional role it is equally true that a man who wishes to look after his children full time may meet equivalent challenges.

The reliance upon theories of ‘essential differences’, and thus the failure to accept the social construction of gender, also has consequences in failing to address the endemic phenomenon of rape. It is to this issue that we now turn our attention.

Sources

Cordelia Fine, Delusions of Gender

Anne Fausto-Sterling, Myths of Gender

S. Rose, R.C. Lewontin & L.J. Kamin, Not in our Genes

Angela Y. Davis, Women, Race & Class

Diane Herman, The Rape Culture

Comments

This is good, I like Fine's stuff. Apparently Rebecca Jordan Young's 'Brain Storms' is a good compliment to Delusions of Gender. Her and Fine were interviewed together on Radio National's All In The Mind last year.

That stuff on 'stereotype threat' is really important too, and the effect holds for other factors such as race and class from what I'd read.

There is a really good article on cracked.com today about five key gender stereotypes which used to be exactly the opposite way round!

http://www.cracked.com/article_19780_5-gender-stereotypes-that-used-to-be-exact-opposite.html

Good article, I've had debates on this issue with one of my sociology professors who is follower of "difference feminism". He contends that biological differences between men and women make it so that the gender gap for wages, careers, and family orientation is based on biology, not social structure, and thus sexism in society is not as prevalent as people think. He always points students towards Susan Pinker's The Sexual Paradox when talking about difference feminism. But it seems like difference feminism is doing exactly what these socio-biologists referred to in the article are doing: taking abstract and not completely understood biological concepts and applying them to social norms.

i read delusions of gender last year, and while i think fine's argument is correct, i found the book hard to take b/c of a needlessly snarky tone and sometimes partial argumentation. but i'd still recommend it.

Rape culture

Polite Ire critiques rape culture, where the use of women as objects is normalised.

Rape culture is more than a society in which the physical act of rape is evident. Rape culture is a culture in which it is a societal norm for women to be objectified, for the fear of rape to be ever present, and where it is accepted that it is not possible to conceive of a society in which rape does not exist. For a more thorough descriptive list of what a rape culture entails, this blog serves as a good guide.

The expectation and acceptance of objectification, harassment, and thus also the potential for rape, is highlighted by a study in which a high percentage of women, working in male-dominated professions, reported experiencing sexual harassment. However, rather than blame the perpetrators, the victims questioned their own sensitivity, and attributed the behaviour to just ‘men being men’ (Fine 73-75). Binary expectations of gender thus contribute to a culture of victim blaming, where it is not the responsibility of men to behave with respect but of women to overcome a perceived weakness in how they respond. For women working in a male dominated workplace failure to accept such a culture could mean losing their own position, thus the choice is either to be a perpetually harassed victim, or an unemployed victim.

The everyday acceptance of such a culture would suggest that ‘the rapist’ is not an exotic and unusual individual, but someone whose behaviour mirrors the expectation of male domination within society. Indeed empirical research has failed to find the “typical” rapist, instead evidence suggests that an environment in which men are expected to prove their manliness, that is to prove their dominance over women, results in a society in which rape is more prevalent.

In our society, men demonstrate their competence as people by being “masculine”. (p.49)

The social requirement for males to perform masculine qualities is thus indicative of a socially constructed gender binary. Where human attributes are divided in two, where men suppress the “feminine” and women suppress the “masculine”, rape becomes “the logical outcome” (Herman 52). Therefore in order for rape culture to be overcome, it is necessary for our society to be transformed into one where both sexes are equally able to access the multifaceted and contradictory human qualities that have thus far been halved.

Much socio-biological research into rape has however concluded that rape is a biological rather than social behaviour. Yet this research has been criticised for basing its conclusions upon extrapolations made from studies upon animals. A study carried out by Thornhill et al concluded that rape had an evolutionary function, serving as a way in which men could reproduce should attempts of “co-operative bonding” or “manipulative courtship” fail. While the study recognised that there are more proximate causes of rape, e.g. the desire to dominate etc, the evolutionary instinct for reproduction is claimed to be the ultimate cause. As a consequence, the conclusion, such as it is, is shown to be utterly facile when met with any degree of contrary evidence, stubbornly repeating “evolution did it”, as examples of other causes, unrelated to reproduction, continue to present themselves (Fausto-Sterling 193).

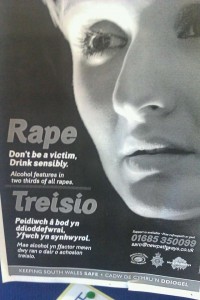

By accepting a biological cause of rape these studies accept rape as an unchangeable part of our society, and has potentially dangerous consequences when considering how rape should be dealt with, both in terms of the potential punishment of the rapist and in regard to rape-prevention – the onus is upon potential victims to avoid rape, rather than upon the perpetrators to not commit it. The responsibility thus falls upon the victim, and examples of this will not be unfamiliar. Women are told how to avoid rape by changing their own behaviour, whether that means not going out alone or not drinking as much; they are told to avoid strangers, and to avoid strange places; they are told to leave extra lights on when home alone, to drive with the doors and windows locked. To avoid being raped a woman must live as if every man she meets is a potential rapist. The message is such that the behaviour of the rapist is effectively ignored. This culture of victim blaming is evident in the 2008-9 anti-rape campaign by South Wales Police, a campaign which included a poster aimed at women that stated “Don’t be a Victim”.

Not only does this poster, and indeed all of the advice described, place responsibility of rape onto the victim, it also ignores the crucial statistics that show clearly that the vast majority of rape is perpetrated by men known to the victim (often partners or husbands) and thus the “advice” is both irrelevant and in fact actively harmful, as it creates belief that rape could be avoided if only women were more careful.

The theory of a biological cause of rape is a convenient conclusion for those who do not wish to see social change. It is a theory that allows men to continue their domination over women and for patriarchal norms to remain unchallenged, as rape is considered an innate evolutionary behaviour. The evidence however is weak, and the counter-argument, that the socialisation of gender roles create norms of masculine dominance that are learned, is far more convincing. Thus rape culture can be challenged, but it must be done on the systemic level; if we truly want to see the end of rape patriarchy cannot be allowed to survive. Rape culture thrives in our society because of the entrenchment of binary gender roles. And it creates a paradoxical situation where men who are kind, considerate, and loving can state with the best of intentions that men should protect the women in their lives, an intention derived from the gender norms that allow men to be a threat. In the words of Mary Edwards Walker:

‘You are not our protectors… If you were who would there be to protect us from?”

Sources

Sources

Cordelia Fine, Delusions of Gender

Anne Fausto-Sterling, Myths of Gender

S. Rose, R.C. Lewontin & L.J. Kamin, Not in our Genes

Angela Y. Davis, Women, Race & Class

Diane Herman, The Rape Culture

Comments

60 minutes - poem from a victim of drug-assisted sexual assault

60 minutes

Please come back

Why are you so afraid to show your face?

Cold floor - Twisted neck

The lifting of a floral petal dress

Was it 60 minutes?

Minutes needed to penetrate my core

Rip out my soul?

60 minutes

Did I tell you no?

Did I cry for help?

Fight you off?

No physical scares to tell the story

Time gone with no trace

Time now my horror

Time now your victory

Your hands and minutes

from a dreaded clock I cannot stop

Can I turn you back, time not mine?

Can't take back - 60 minutes not mine

60 minutes - the sun rises

My night stolen my morning broken

60 minutes - to drive home

Blood, aching, confusion, shame

60 minutes - to decide

This secret horror will be mine

60 minutes at my desk

Countless questions

Anxiety rising with each breath

Collapse, ambulance, more questions

60 minutes with a social worker

60 minutes with a detective

60 minutes awake in the ward

The lonely early hours

Heart monitored, wires, beeps

No sign of life

Can they not hear it does not beat?

60 minutes at forensics.

Naked in a robe. Identity lost.

Rape victim. Rape survivor.

Robe is chains.

Swabs and plastic bags.

Legs apart. My pain exposed.

Scrape out that demon inside.

Hairs, saliva, semen, body fluid

60 minutes of scouring the corpse

Vultures hovering above remains

60 minutes to tell him

Blame me. Blame other. Blame you.

Anger.

60 minutes of tears. 60 each day thereafter.

60 minutes with police.

60 with victim support.

60 minutes with crisis line.

60 minutes sharing with a colleague.

Time ticking as I am judged.

Seconds evaporating as rumours spread.

Not believed. Mad.

60 mins on the clock with a lawyer.

60 for free with the doctor.

The predators game.

Predator poised ready to spring.

60 of despair in a doctors room

Held close, safe at last

60 on the phone

Ravished, taken.

Prescribing his poison

Pills to mask whose pain?

To hide whose shame?

60 a day

With crushing structures

Social, political, legal

David and Goliath

Where are the people?

Where is the voice?

Who hears the muffled screams?

Raped of all power.

60 minutes in a job interview

Not ready but no money

Structures and systems

Capitalism forces my hand

60 minutes to lose my job

Room with no window or witness

Lies and betrayal

Told I won't recover, ever

Tears fall

To dissolution , oblivion

60 minutes to learn to hate

60 minutes it felt like

7 hours of mediation

Suicide watch - watching

Drugged again by my illness

Patchy memory, poor recollection

Prostituting my soul to settlements and gagging orders

Now twice to that which controls me

Raped of my ability

Society nonchalant to my needs

The pillaging of what has been conquered

60 minutes with the truth

60 of trust in a truth teller

Voice heard, story told

Memory stolen

So much taken

Voice remains but fading

Will they hear?

Are these the dying words?

Epilogue of trauma and social struggle

60 with a therapist

Not more, not less

Caring so fluid

Eyes that remain

Words so guarded

Engaged in mind

Tentative heart

Subtle powerful communication

Attuned but repressed

60 minutes - stealing hours

60 minutes

Seconds putting distance

Between forgotten minutes

and the future ahead

Time heals

Will it?

But does it ever remember?

And then will it forget?

Will 60 minutes change anything except for me?

Gender and the state

Polite Ire looks at the links between gender and the state, arguing that masculinity is constructed in the image of the state.

Politics is dominated by men. Indeed when David Cameron was accused of being sexist, he responded at the next PMQs by ensuring there were a number of female MPs sat behind him, presumably in an attempt to show that women were represented in his government. However, women hold only 16% of government seats, and only 22% of parliamentary seats as a whole. Despite equality legislation, despite the ability of individual women to work within the parliamentary system, as a whole the structure remains dominated by men – a state of affairs that is entirely predictable given the socialised gender norms discussed in part 1.

When Cynthia Enloe theorises women in politics she points to the evidence of socially created gender norms, however she does so in a manner that continues to accept the division of masculinity and femininity between the sexes – i.e. women need to be involved in politics in order to bring feminine views to this otherwise masculine sphere. This analysis would suggest that political structures continue to be male dominated because men have traditionally held power and wish to keep women subservient, and thus it follows that gender inequality can be solved by more female representation within political institutions. She writes:

the conduct of international politics has depended on men’s control of women (Enloe p.4)

While on the surface this seems a plausible explanation for a patriarchal structure, i.e. that men create structures to further their own interests, it also implies that men have constructed gender roles for women, and thus fails to appreciate that the gender role of men is also a product of social construction. In other words her argument suggests that men have agency because of… the agency of men! By recognising that the creation of gender norms is far more complex than attributable to the agency of men, we must also question why masculine traits are regarded as political attributes.

The binary nature of gender stereotyping is paralleled in Machiavelli’s The Prince. In this he writes of dichotomous qualities that bring either success or failure to a Prince, these most notably (for our purpose here) include effeminate and weak versus fierce and bold. But stereotypical gender qualities can be read into others, including: generosity/greed; cruelty/mercy; and lasciviousness/chastity. For Machiavelli’s Prince, success is determined by the qualities he possesses, and it is notable that the statesman who embodies the qualities we more regularly attribute to men is the statesman who enjoys success. Could it therefore be claimed that the functioning of the state system requires the gendered division of human attributes? When theorists of international politics suggest that the ‘masculine’ state is a reflection of human society, are they correct in their labelling of the cause and effect, or could in fact our gendered societies reflect the requirements of a state system?

When Enloe writes of self-determination in post-colonial countries, she talks of the difficulty in ensuring nationalism works for women as well as men. The complexity, she claims, stems from nationalistic men who view women as the property of the community, those who will give birth to future generations of nationalists and ensure the continuation of shared values and traditions. However this role of the nationalist woman also leaves her vulnerable; if she is assimilated into another culture, the future of the nationalist cause will be lost. For Enloe ‘awareness, questioning, and organising by women’ (p.13) is needed to ensure that the patriarchal norms of the former colonial ruler are not perpetuated by a nationalism built upon the repression of women (and/or for indigenous patriarchal norms to be challenged through the struggle for self determination). Her criticism of nationalism is again one of representation; it is problematic only because women do not hold decision-making roles – i.e. nationalism reflects society. If instead we theorise that nationalist movements reflect their ambition of state power, we can then suggest that in order for a nation to succeed as a state it must adapt its society to function within the state structure. The subjugation of women is, therefore, not the free choice of powerful men, but one that is dictated by a structural necessity to divide the ‘masculine’ and ‘feminine’, and subordinate the latter to the former.

If evidence for innate gender differences cannot be found, then gender inequality cannot be explained by essentialist arguments. If Michael Kimmel is correct when he suggests that ‘gender difference is the product of gender inequality, and not the other way around’ (p.4), then the only answer to inequality, the only way to break from patriarchy, is to radically change our societal structures. Without such change we have only the hope of reform, promising much but in reality changing little. If there is no innate difference in gender, Enloe’s proposed solutions will not change the repressive gender roles of patriarchy; the structure of the system itself relies upon the repression of half of human attributes, i.e. the “feminine” attributes. Using the oft cited example of Margaret Thatcher, this theory would therefore not claim that she acted ‘like a man’, but that she acted like a politician. The individuals who work within and uphold these power structures, whether male or female, must suppress the qualities that are not beneficial to the continuation of the structure, thus also maintaining the socialised differences that create inequality.

Feminist scholars of political theory assert that ‘the personal is political’, i.e. private interpersonal relationships are power relationships. In regard to rape culture, this means that:

‘Rape… is about power more than it is about sex, and not only the rapist but the state is culpable.’ (Enloe p.195).

While this indicates recognition that socialised gender norms create rape culture, it does not go far enough. In its failure to account for why politics is masculinised, indeed why the state structure requires this masculinisation, it cannot satisfactorily theorise a society without rape culture. If the state can claim a monopoly upon legitimate power, and the state is inherently masculine, the subordination of the feminine is inherent to state societies. Enloe’s conclusions continue to fall into the same trap of the essentialists, i.e. seeing men and women as fundamentally different. As a result the liberal empowerment of women is actually only surface level change – legislating over the cracks but ignoring the depth of the problem. The subordination of women, and the rape culture that accompanies such gender hierarchy can only be truly challenged on the structural level; this challenge must therefore be against state structures, and therefore also capitalism, as the capitalist system cannot survive without the state. As noted by Angela Y. Davis:

“As the violent face of sexism, the threat of rape will continue to exist as long as the overall oppression of women remains an essential crutch for capitalism.” (p.201)

Sources

Michael Kimmel The Gendered Society

Cynthia Enloe Bananas, Beaches and Bases

Niccolò Machiavelli The Prince

Cordelia Fine Delusions of Gender

V. Spike Peterson (ed) Gendered States

Angela Y. Davis Women, Race and Class

Comments

Gender and protest

Polite Ire argues that patriarchy cannot be challenged without taking on capitalism and the state - and vice versa.

The necessity to challenge state and capitalism in order to challenge patriarchy means gender norms should be consciously recognised and confronted by those protesting against these structures.

Women are often represented within a protest as being passive and peaceful; any violence generally attributed to young men. This misrepresentation is more easily made due to the gender associations previously discussed. The gendered descriptions of protest as reported by the news is also reflected in how protests are later remembered, thus allowing them to be appropriated for political ends. This is evident in the treatment of the suffragette movement, cited by politicians as evidence of the success of peaceful protest, ignoring how the fight was won by campaign tactics that included window breaking, attacking MPs, arson, and suicide. Militancy was openly called for:

“There is something that Governments care for far more than human life, and that is the security of property, and so it is through property that we shall strike the enemy. Be militant each in your own way. I incite this meeting to rebellion.” (Emmeline Pankhurst)

The suffragettes then were far from peaceful. Yet it is easy for Ed Miliband (and many others) to claim that it was, and this is in part due to the expectations of the listeners: women are “more likely” to act peacefully. This is evident in Miliband’s other example, that of the Civil Rights movement in the US. While Martin Luther King’s peaceful methods are extolled, the campaign of Malcolm X, which rejected non-violence, is an obvious omission. While the suffragettes were also split into non-violent (the NUWSS) and violent groups (the WSPU, led by Emmeline and Christabel Pankhurst), the ability of modern politicians to claim them all as peaceful – despite the most famous advocating violence – can in part be attributed to our socialised expectations of how women act. Indeed in the UK ‘suffragette’ was used primarily to describe the militant WSPU, ‘suffragist’ being used for the peaceful NUWSS. When politicians today call for peaceful marches and negotiations, using the suffragettes as an example, they are playing on our socialised gender roles in an attempt to stop us from acting. This is quite contrary to the suffragettes, who called for “Deeds Not Words”.

The misrepresentation of women’s actions is therefore problematic for protest movements, fictionalising events in order to conform to gender binaries. Where actions themselves are not altered, women are often rendered invisible, men assumed to make up the majority of protestors. This is particularly of note in public sector strike action; while 60% of public sector workers are women, the stereotypical picket line, and therefore the stereotypical worker, is predominantly male. When politicians and newspapers argue against industrial action they are assisted by this stereotype, for example in calling on women as mothers to speak out against teachers strikes – a call that ignores the role of women as workers, indeed mothers as workers, and gives greater importance to a day’s education than to parents ability to provide food and shelter for their children. The targeting of women as mothers is also evident in election campaigns, with women often shown with children, or explicitly asked to vote for the benefit of their children’s futures. No such plea is made to men as fathers; it appears that men should act based on rational, political and/or economic grounds, and women for emotional reasons.

The problems of patriarchy, rape culture, and socialised gender norms have all been evident within the Occupy Movement, the issue made stark after the rape at Occupy Glasgow on 26 October 2011. The initial statement made by the Occupy camp was widely criticised for distancing the protestors from the victim, both by citing the woman’s homelessness and their attempts to provide food and shelter, and by downplaying the seriousness of the attack by labelling it a ‘sexual assault’ as opposed to a gang rape. This statement was later retracted. However, the Occupy camp continued to have problems, their facebook page suspending comments after users continued to marginalise and blame the victim, in comments such as:

‘Anyone who criticised the Occupy Glasgow Movement for last nights [sic] events should try and work with the homeless in the city centre’

In order to address the concerns arising from the rape and the subsequent response, a women’s working group was proposed and set up. However, the lack of recognition of women’s vulnerability and marginalisation created divisions on this issue. A number of protestors, while advocating gender equality, refused to accept the idea of a women’s group, labelling it divisive. Arguments such as ‘too many divisions, we’re all the one species’ and ‘Don’t do it alone – men and women together – no more walls – break the barriers down!’ were numerous, and demonstrate a failure to consciously challenge patriarchal norms. However, there were also more antagonistic comments, accusing those who called for a pro-active approach for women of being

‘… millitant [sic] feminists… like joke characters… hysterical… [and] determined to bring down this protest’

Comments such as this show how stereotypical gender norms are prevalent within the Occupy movement (and within protest movements more generally), and provides an example of how an explicit statement of intent to challenge oppression does not necessarily lead to a conscious challenge against patriarchy. In ‘structureless’ groups, such as the Occupy camps, socialised gender norms ensure that, by cult of personality, men will hold more of the unofficial ‘leadership’ roles. As a result of this, women’s groups are required in order to allow women a safe environment in which to speak of issues that make them vulnerable under patriarchy. The point of such a women’s group is to help create the conditions in which such groups are no longer necessary.

The gender norms prevalent in society at large thus also affect the makeup of political movements and groups. In order to challenge these gender norms groups must do so as part of the struggle, or else any gains made will be done with patriarchal norms and structures still in place. Inequality must be consciously recognised, and consciously challenged; any political group must seek to act in accordance to the principles they wish to see enacted in society at large. However, doing so may require compromises along the way: the creation of true gender equality may require a period in which women’s groups are active; allowing women the confidence to speak without being marginalised until such a time as the norms have been challenged sufficiently for such groups to no longer be required.

Conclusions

In parts one and two we saw how binary gender norms and roles are created by socialisation, having an effect upon how we experience our everyday lives, the chances we have in gaining particular jobs, and the way in which we might expect others to react should we challenge these expected behaviours. These socialised gender norms are a foundation of patriarchy, a structure that also allows the enduring existence of rape culture. This section also questioned the theory that rape is a result of biology, arguing that rape culture is born out of the socialised division of masculine and feminine qualities. It was argued that in order to end rape culture we must challenge the binary gender norms our society produces and supports.

In parts three and four it has been argued that politics is a masculine sphere because the state structure requires the repression of ‘feminine’ attributes; the state system is thus culpable for the socialised gender norms discussed in part one. This is also a reason why women remain underrepresented – and yet their representation will not help challenge patriarchy, as politics itself remains masculine, and feminine qualities in a politician (of either sex) will remain a weakness. Therefore for patriarchy to be challenged, for rape culture to be abolished, requires a radical changing of our societal structures, going as far as that of the international state system. This creates a challenge for protest and political groups who seek to challenge current political systems. It has been argued that patriarchy must be challenged within the everyday functioning of a protest group, consciously recognising the issues of gender and seeking to overcome such power imbalances and attempting to replace divided gender norms into more complete human norms.

Sources

Michael Kimmel The Gendered Society

Cynthia Enloe Bananas, Beaches and Bases

Niccolò Machiavelli The Prince

Cordelia Fine Delusions of Gender

V. Spike Peterson (ed) Gendered States

Angela Y. Davis Women, Race and Class

Comments

These Polite Ire articles are fantastic. Please upload more if there are any.

The way black bloc is often presented in terms of gender I think is especially interesting. Far from being a manifestation of hypermasculinity, as Chris Hedges and others tell us, black block and similar tactics are a manifestation of a transcendence of gender. The anonymity vis a vis personal identity "blocking-up" offers extends to gender identity. Black bloc is an attack on gender, not a reinforcement of it. Those who criticise it as being otherwise reveal their own sexist prejudices. Yes, believe it or not, women do riot. Organised feminism has its roots in rioting and vandalism. Before women were engaged in wider political processes, they rioted and these riots acted to transform woman from abstract universal to conscious actor, a force to be both recognised and reckoned with.

Comments