The article below was sent to the ICC by a comrade in Japan: it describes the emergence and decline of the squatters' and day-workers' movements which have marked the life of several Japanese cities - more particularly Osaka in this case - since the collapse of the Japanese economic "bubble" at the beginning of the 1990s, to the present day.

The article below was sent to us recently by a comrade in Japan: it describes the emergence and decline of the squatters' and day-workers' movements which have marked the life of several Japanese cities - more particularly Osaka in this case - since the collapse of the Japanese economic "bubble" at the beginning of the 1990s, to the present day.

Our regular readers may be surprised by the somewhat "literary" style that the comrade adopts. This does not in our view detract from the significance of the events that he describes, and indeed it rather enhances some interesting reflections on the way in which the capitalist productive process organises geography and time.

Historically, there has always been a deep divide between the workers' movement in the industrialised West and the East - in Japan and China in particular. This was largely inevitable given the late arrival of the Japanese and Chinese working class on the historical stage (see our articles in the International Review) and the barriers of language.

The bourgeois media in the West have always worked to emphasise this divide (though usually with more subtlety than Edith Cresson (French Prime Minister 1991-92) who described the Japanese as "yellow ants"!). Japanese workers have been shown as going on "strike" by putting "unhappy flags" on their machines while continuing to work. There was even a short-lived vogue amongst management theorists for Japanese-style "quality committees" where the workers themselves could suggest improvements in the production process. The Japanese workers were presented to their class comrades in the West as hardworking and patriotic contributors to the Japanese "economic miracle", from which it has usually been implied that they profit at Western workers' expense.

Not only that: the workers in Japan supposedly enjoyed the supreme happiness of being guaranteed "jobs for life" thanks to the paternalistic attention of the Japanese mega-companies - something which supposedly set them completely apart from workers in the West.

The article below has the merit of blowing a hole in this completely fraudulent picture of Japan. Here we see the masses of impoverished day workers in struggle against the barbaric exploitation inflicted on them by the almost indistinguishable forces of the state, the bosses, and the mafia (yakuza). But we also - and the author is absolutely right to point this out - see that this is not limited to the most downtrodden sectors of the working class: the whole Japanese "economic miracle" has been founded on the increasingly ferocious exploitation of the entire workforce: factory workers and office workers, but also technicians and scientists as skilled jobs are proletarianised.

In our view, the events described in this article are more than just riots. They are clearly a workers' struggle, fought on the terrain of the working class: initially sparked off by an expression of solidarity with a victim of police aggression, drawing in workers and their families from the entire Kamagasaki area, and directed not only against the police but against employers trying to swindle workers out of their wages.

Western readers may recognise some similarity between the events described below, and the situation in certain European countries during the 1970s. The internal immigration towards cities less touched by the crisis, leading to a housing shortage, property speculation, rack-renting, and the squatting of empty property, was a large-scale phenomenon in London and some Dutch cities during the 1970s for example, although not on the same explicitly working class basis: the social composition of the squatters' movements in Britain and Holland was much more mixed.

Western readers will also recognise the manner in which the Japanese state has dealt with the movement in Kamagasaki: "NGOs replaced the direct discipline of police batons as their mediating roles were appreciated by the city in halting unrest (…) newly radicalized unions, who quickly transformed into facilitators of ritual action: such as protest marches completely surrounded by police". This is precisely the role that has been played historically by the trades unions, ever since they betrayed the working class by giving their support to the imperialist slaughter in 1914. Especially under bourgeois democracy, where they benefit from the appearance of separation from the state, the unions are able to achieve results that the police cannot, by sabotaging the struggle and preventing its self-organisation and extension rather than by open repression. A classic example is the role played by the newly formed Solidarnosc union in sabotaging the workers' struggles in Poland in December 1980, delivering the proletariat, bound hand and foot, to the state repression that followed a year later. In Osaka, once the NGOs and the unions have done their work, the squatters' tents which had once symbolised workers' resistance have become nothing but an empty shell, easily emptied by the police.

The value of this article lies - amongst other things - in its clear demonstration that the workers in Japan face the same problems, and the same enemies, as workers in other parts of the world: one more demonstration that the class struggle is international, that the working class is a world class.

All this being said, the article also contains a certain number of ambiguities, or perhaps we should say internal contradictions, which in our view detract from the force of the argument. There are three which seem to us particularly important.

1 - The first, is the role of the unions and of the left generally. While the article in effect denounces the union sabotage of the struggle (see the quote above), elsewhere it seems to suggest that there is a fundamental opposition between the unions, the left, and the "neo-liberal project", and that the collapse of the former in Japan made possible the success of the latter.

But the attacks on the working class from the late 1970s onwards were by no means a Japanese, they were a global phenomenon. The onset of the first post-war crisis in the late 1960s led to an enormous world wide wave of workers' struggles - of which May '68 in France was only the most impressive moment. The end of this wave of struggle was inevitably followed by a capitalist counter-attack, whose aim was to make the workers pay the price of the crisis that had opened up from the late 1960s onwards. The role played by "the left" in the resulting defensive struggles of the working class - when left governments were not directly imposing austerity themselves, as the "Socialist" and "Communist" government did under Mitterrand in France - was to sabotage the workers' efforts to react by making sure they never escaped the narrow boundaries of corporatism and nationalism (the "coal not dole" slogan and the campaigns against imports of Polish coal during the British miners' strike in 1985 are a clear example). The idea that the workers' struggle "re-composes" into unions and that the result, "far from being exterior to the ‘being' of the class which must affirm itself against them, [is] nothing but this being in movement", obscures the profound opposition between the permanent union structure and the needs of the working class in struggle: this is easily verified in practice by anybody who has tried to oppose workers' initiative to the union line during a mass meeting. More profoundly, this opposition arises from the impossibility today (contrary to the period prior to 1914) of the working class creating permanent mass organisations.

2 - The article's second ambiguity lies in the suggestion that it might be possible to create an "autonomous" space outside the institutionalisation imposed by the capitalist state (notably in its "welfare" version). This, it seems to us, contradicts the article's otherwise striking descriptions of capitalism's totalitarian domination of social life, from housing, to transport, to work, and right down to the helping hand and the friendly smile transformed into waged activity. It is this second emphasis in the article which seems to us correct: the idea that it is possible to create "islands of communism" or even "islands of autonomy" within capitalism, is simply an illusion. The experiment was tried repeatedly at the very beginning of the workers' movement, in the days of the Utopian socialists Fourrier, Cabet, and Owen: it was tried, and failed - 200 years on, the illusion belongs firmly in the past, not in the present. This is true even for more limited experiments: as Marx pointed out, in any society the dominant ideology is the ideology of the ruling class, and it is impossible to achieve "autonomy" from this. It will take whole generations after the revolution for humanity to "rebuild" itself, to rid itself of all the ideological muck accumulated in millennia of class society.

We can be inspired and touched by the spontaneous humanity of the homeless in Tennoji Park (see note 8 of the article), but this does not provide an organisational lesson for the struggle of the proletariat as a whole.

3 - The contradiction we have just described is at its most ambiguous in the final paragraph, where on the one hand the author advocates a struggle with "no commitments, no demands as such, no gathering points and thus no encirclement", yet at the same time posing the question of "how an autonomous space can develop against the crushing weight of capitalism". But what is a "social space" with "no gathering points"? What could it be? Surely nothing other than a contradiction in terms.

In Russia in 1917, the Russian workers did not confront the Cossacks (the riot police of their day) on their own terms, they dissolved the Cossacks' power. They were able to do this because the proletariat represented a massive and organised force able to take decisions as a class and to present a vision of the future that stood firmly and radically against the barbarity of capitalism. The road to revolution leads not through riots born of and ending in despair, but through massive, open, conscious struggle, able to assert its own perspective against capitalism's "no future", to the point where even the riot police begin to doubt themselves.

International Communist Current

You must help yourself: neo-liberal geographies and worker insurgency in Osaka

"I realize as the train pulls in that the station is on fire. The platform is aflame and below the streets are empty with people running past occasionally. Something is happening. I pick up some rocks and start throwing them at a police line"

– anonymous rioter at Kamagasaki

.

"You must help yourself"– Ilsa, She-Wolf of the SS

Confronting the riot police

October 2nd, 1990. The day started as any other does in Osaka's Nishi-Nari ward, men lined up around the yoseba employment center, in the thousands, waiting for work. If it came, they would load into the cars of construction contractors in groups, with parachute pants and wrapped heads. For eight hours they might wave light wands ‘guiding pedestrians', dig concrete roads, re-pave highways or variously break their backs in the sun. This proletarian fate was ceded by the city's bourgeoisie over a period of thirty years of continuous unemployed unrest; all the union officials touted it as labor ‘won' from an inhuman system. After all, without work, one does not eat, and once conditions have worsened to the point that this phrase becomes dictatorial, one works in a fervor; for work leads to ‘independence'. Work might one day lead out of the slum.

If work didn't come, the men wait out lunch and line up for the daily workfare handout, set aside for ‘unsuccessful job-seekers'. This yoseba is in Kamagasaki, a neighborhood of poverty and celebration, a breathing lung, where the yakuza patrol day-workers with icy looks and stashed weapons; at occupied ‘triangle' park, men, dogs and blue canvas spill out into the street sides. Udon and soba are served at improvised stool stands roofed with canvas. Women and men prepare boxed lunches, noodles and Okinawan fare at shops lining the crowded avenues. Just to the east the brothel neighborhood of Tobita sits in expectant dormancy, for the night will soon fall. The slum is quiet.

For the city hall and the construction capitalists, it was just another Tuesday.

There were multiple flashpoints, like any riot, origins that became history for the individuals and groups that experienced them. For most, the riots began with friends running past, heaving paving stones at the police. But most will point to an account of an old homeless man in the Namba theater district, north of Kamagasaki. Police on patrol had stopped at his improvised blue canvas house, berating him to leave the sidewalk. The man (known by most as 'a bit bizarre') unleashed his dog, which quickly sunk its teeth into a senior patrolman. After a struggle, he was surrounded by police and beaten as a crowd gathered, consisting of other homeless people and some day-workers. Hauled away and arrested, the angry crowd followed the car to the Nishinari police station.[1]

News spread on sprinting legs to the enormous yoseba hiring hall in the south, circulating among groups of day laborers. Without any particular confrontation, a few ‘troublesome' workers were pulled aside by the yoseba police patrol and in front of thousands, beaten. The neighborhood exploded. Yoseba day-workers, witnesses in their thousands, took their comrades back and drove the police from the hiring hall, swarming outward like blood through Kamagasaki's lungs. Crowds formed here and there, with a general movement towards the police station, from which the police re-emerged. A rain of stones fell. After the volleys reached a temporary abatement, barricades were quickly erected, bicycles ignited with cheap lighter fluid, stacked and burned, dumpsters dragged into the street. Capital's tendency to crisis, the proletarian form, was erupting.

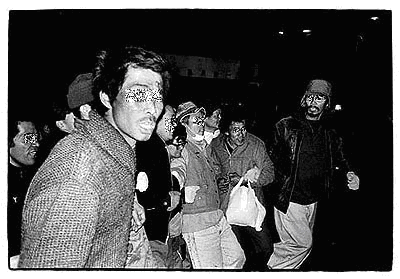

Workers in the streets

The police retreated in order to barricade the neighborhoods, to shut off the arteries that connect Kamagasaki to the north, south, east and west. A classic siege strategy was put into action punctuated by sudden, violent streams of steel-shield armed police into the neighborhoods. Mobile riot squads surrounded the area with armored buses and paddy wagons, and soon lined the boulevards in columns with five foot steel shields. All the forces of government and private capital arrived to contain thousands of revolting workers and rapidly arriving allies, to circumscribe a space that was impassable for the surging rage of the rioters.[2] Media vans pulled up and were stoned if they attempted to penetrate the riot line and ‘get the real story'. In several cases cameras were sought after and smashed.[3] All footage of the events comes from behind police lines. Advances by the cops were met with volleys of objects flung from the parapets of apartment buildings by the unemployed, workers and housewives. At times, the riot constituted itself as a castle pocked with archers. When the first barricaded day slipped into night, the cars of the construction barons were smashed and degraded. Parks that had been evicted of squatters had their locks broken and were re-taken.

The insurrection faced its own limit, against the borders of space drawn by the state and its own projectuality. Discussions arose everywhere on where to go next. Many feared that the riotous action would blacklist the neighborhood from construction contracts, that the yoseba would close like the one in Tokyo had just a year earlier, that poverty would worsen. Most gazed over the surrounding steel buses of the riot police and saw the impossibility of expansion, of the riot spreading to other sectors. NGO workers and city hall mediators arrived urging people to ‘calm down', that police violence could be ‘addressed'. But these particular beatings were only moments on a continuum of violent surveillance and control. There was no doubt that the situation was in fact rapidly worsening as police ran wild in the streets, smashing skulls and faces with steel pipes and shields. The Kamagasaki population was at open revolt with the organs of repression, most saw no way back to ‘normality'. Buses and sound-cars of the unions and organizations of the unemployed mobilized from their garages and circled the neighborhood, providing a temporary barrier; they eventually moving through police lines, broadcasting messages to a wider portion of the city. Night fell again.

"I edged back to the crowd. From behind me, someone yelled ‘Aim for the lights!'. Stones were thrown aiming towards the lights of TV cameras stationed behind the riot squad.

I entered the crowd. No one took any notice of the camera that I held in my hand. After a while, a man spoke to me. ‘Are you from the news papers?' When I answered no, he said, ‘If you are, you are going to get killed.'" (-anonymous observer at Kamagasaki )

As the riot entered into its third, fourth day the city's strategy was in continual escalation. The rioting, unarmed workers were meat for the mobile riot squads. Largely defensive formations changed into charges, five-foot steel shields were leveled against the flesh of the disgusted. Barricades collapsed or were extinguished, and the police made real progress into the neighborhoods. If the streets could be cleared, then the tear-gas buses and paddy wagons could move in. Hundreds of the most militant were chased south into a union building where the insurrection made its last, unarmed stand. Concurrently and further south, partly in inspiration from the Kamagasaki rebellion, a youth revolt had exploded, spearheaded by ‘speed tribe' gangs on motorcycles who fought the police in skirmishes. This rebellion was contained even quicker, and most of the young rioters found themselves chased into the same building with the older workers.[4] There would be no cavalry for Kamagasaki.

The building was taken with tremendous violence. The 22nd riot in the neighborhood's 30 year history had ended.

Despite the arrest and imprisonment of many, over the next four years there would be more small riots, sporadically, where the police or contractors were targeted. When unrest broke out, other workers would come running; construction contractors dodging back-wages found themselves at the mercy of mobs. People took inspiration from the riots that raged through the neighborhoods throughout the 1960s, contestation, above all was the agenda!

The strategy against the riot by the city and the bourgeoisie was drawn from every lesson learned in the past forty years of class struggle in post-fordist Japan. Initial direct force, followed by the deployment of mediators, the deployment of advanced technological means of repression, filtering of news about the riots, news blackouts, concluding in total geographical isolation of the proletarian ferment. Riots can not be permitted to spread to other sectors, and therefore Japanese capital's only strategy against the eruption of its own contradictions is containment.

MUZZLED CONTRADICTIONS, STRANGLED PROLETARIANS

Tent city in Osaka

The riots of the 1990s took place amid the massive restructuring of the 1980s and the economic crisis of 1989 as the investment ‘bubble' burst and the promise of a Japanese 'prosperity' proved hollow. Already migrant workers from Okinawa and Tokyo had taken up park occupations all over Osaka, not to mention Nishi-nari ward and the Kamagasaki neighborhood. Improvised huts, roofed with blue tarp, decorated with paint, junk, sometimes city free jazz schedules and at the very least posters of famous female crooners holding beer mugs, sprung up all over the city. The huts were statements of autonomy, arising from the immediate inability of newly-arrived workers to afford housing; as a strategy the ‘tent villages' blanketed the city, in order to stake out an existence independent of the welfare state's institutionalization. Out of the riots, the workers' movement in Kamagasaki re-composed into union coalitions. NGOs replaced the direct discipline of police batons as their mediating roles were appreciated by the city in halting unrest.[5] 16 surveillance cameras at major intersections and shopping streets were installed in Kamagasaki alone. Over 1990-1995, the men at city hall dumped all the previous strategies, and Kamagasaki moved from a zone of discipline to one of control, from containment of outburst to total regulation; the unemployed were channeled, mediated and surveilled like never before; what could once communicate itself as a struggle of autonomy against the control apparatus was now more and more forced to speak the language of social peace. Park occupations were slowly apologized for as a response to the poverty of the city's institutional shelters as well as the lack of viable jobs, instead of their obvious essence, areas autonomous from capitalist time, characterized by relaxation, karaoke songs and games like go and shogi. The occupations were attempts to attain a moderately bourgeois standard of living, actualizing in motion, against an ocean of industrial poverty.[6] Continual violence and harassment by yakuza and police managed to dull the direct-action strategy of spiteful day-workers as well as the heaviest strategies by newly radicalized unions, who quickly transformed into facilitators of ritual action: such as protest marches completely surrounded by police, food handouts and supplication to city officials at any level of struggle.

"As real subsumption advanced it appeared that the mediations of the existence of the class in the capitalist mode of production, far from being exterior to the ‘being' of the class which must affirm itself against them, were nothing but this being in movement, in its necessary implication with the other pole of society, capital."

NEO-LIBERALISM: TRANSFORMED EXPLOITATION, TRANSFORMED GEOGRAPHIES

Outside of Kamagasaki and Osaka, across the social terrain of Japan, the neo-liberal project had been advancing at least since the collapse of the new left in the late 1970s. A near collapse of the social safety net ensued: previous welfare guarantees were transformed increasingly into workfare, an entire landlord class was born atop workfare-registered workers struggling to pay ‘discounted' rents on yoseba wages. The retirement age was officially moved from 60 to 65 for most businesses in 2005, completing an already unofficial shift planned long-term by the LDP; a whole generation of parents suddenly found themselves working longer and harder and by desperation turning their children's' schools into factories for the production of workers who could support them post-retirement, as pension guarantees seemed bound for an irreversible crisis. Elderly workers who laid-off in the crisis often found themselves on the street with no employment prospects. Among the bourgeoisie, support for privatization and the gradual wearing away of the ‘welfare state' gained steam.

Nothing characterized the period more than speed-up. With the unification in the late 60s of train lines around the country under the JR Company and the rapid acceleration of bullet train technology, capital smoothed space towards a white plane, one with no resistance to the circulation of raw materials, labor power and surplus value. Highways brought the same changes, and inside the workplace a collapse of the labor movement ensured human beings snared in 60-70 hour weeks became the norm for full-time employees.[7] The individual experience of labor became more and more an endless conveyor belt between home, transit and the workplace. A metropolitan factory modeled on assembly lines, bound by its very constitution, to disaster.

ENCLOSURE, SPEED, DISASTER

As an island chain along major fault lines, Japanese civilization is fraught with constant disaster. The 1995 earthquake in Kobe was only the most recent massive demonstration of the power of continental plates (5,273 people were killed, most crushed to death in the collapse of their houses or consumed by the fires that followed the earthquake, 96.3 billion dollars of damage were assessed). Earthquakes are phantoms, haunting all considerations of the future. Last December, a scandal broke in the news media; Hidetsugu Aneha, a 48 year old architect working at a construction firm called Hyuza in Tokyo had, under pressure from his superiors to cut costs on the buildings he was designing, reduced steel reinforcements in building skeletons and falsified data to cover his tracks. As his actions were uncovered and an investigation was launched by the city, it came out that the building for which design statistics had been falsified was not a lone example; the number quickly mushroomed, resulted in the implication of 78 hotels and buildings as being at 30-80% of minimal earthquake preparedness, meaning likely collapse during a strong earthquake. In his defense Aneha protested that when he raised these issues to his superiors they told him the firm would simply lose the contract to other firms if proper costs were covered, and so he must cut expenses any way he could; Aneha's comments therefore implicate not only himself and his corporation, but the construction industry as a whole. These vast, condensed metropolises of the Japanese islands contain millions of bodies on foundations increasingly precarious, and despite the spectacular efforts by city governments at reform and revision, thousands will not survive the next earthquake (as many were killed in recent Niigata prefecture earthquakes). Capitalism has developed all formalized dwellings, all massive dormitories of the exploited that stretch from the city to suburbia, into potential coffins.

In ironic contrast stand the humble hut-dwelling day-workers of Osaka whose low-impact ‘outside dwellings' are in no danger of killing them during a disaster.

In 1987, Japan's nationalized train lines were divided into west and east and privatized. Adding a profit motive to trains, already circulating on the rhythm of breakneck post-Fordist Japanese capitalism, guaranteed the narrowing of bottom lines and an amplified pursuit of speed between stations. In 2005, a rush-hour train derailed between Amagasaki station and Takaradsuka station north of Osaka. The young train driver had been berated repeatedly by supervisors and his supervising senior driver to cut seven minutes off of the recommended transit time for the 25 km between these two stations. The train derailed, traveling at a tremendous speed and collided with a large apartment building, destroying part of its foundation and causing the building to collapse on top of the train car. 105 people died either instantly or before rescue workers could reach them. Unfortunately for the bureaucrats and company officials rolled out to the scene to beg apology (and for all who ride these trains) no uptake of individual responsibility for this massacre can erase the obvious but unspeakable culpability of the economy, cloud of massified instrumental necessity, which by shearing away life-time from the individual worker according to its internal pressure, must constantly flirt with cheap materials and disastrous speed. The reaction of the individual: ‘Where is my train? My son is waiting.' gives form to this pressure. Universal demand for the reduction of transit time, born out of the stubborn intransigence of work time, pushes the trains faster and faster. The social pressure of work time against life time produces derailments, just as the concrete capitalist organization of geography ensures this acceleratory dynamic across space. Crisis is therefore implicit in the accumulated forms of capitalist working class subsumption. To which again, capital can only respond with containment.

"When the ship goes down, so too do the first class passengers… The ruling class, for its part incapable of struggling against the devil of business activity, superproduction and superconstruction for its own skin, thus demonstrates the end of its control over society, and it is foolish to expect that, in the name of a progress with its trail indicated by bloodstains, it can produce safer (trains) than those of the past…"

DISINTEGRATING WORKPLACES; ANTAGONISTIC SPACES

During the neo-liberal wave, an expansion of ‘irregular employment' brought about the birth of a precarious class of workers that would precede Europe's ‘precariat' in conditions if not consciousness. It would also create new forms of social labor that were 'out', roving the cities.

Inside workplaces, an increasing concentration of fixed capital within factories accompanied by off-shoring meant that Japanese government had a mostly idle labor force, steadily being undermined in its real conditions of subsistence by welfare reform, one that could be put to work in entirely new ‘service' industries. Jobs were invented. Escalator girls, elevator girls, kyaku-hiki (customer pullers), street megaphones, flyering, etc. new ‘services' that were above all ‘out and about', social forms that seized forms of inter-human sociality, the tap on the shoulder, the kind holding of the elevator door, the smile, amplifying them, valorizing what had been mostly unwaged action. Population shifts led to the unavoidable importation of foreign labor, causing a gradual cosmopolitanization that has thrown the idea of a ‘Japanese' identity into crisis, while also strengthening reactionary ideologies that take strength from it. The growth of an English education industry brought thousands of temporary workers to Japan, and with them, historical methods of class struggle that clashed strongly with Japanese welfare state compromises of the 70s and 80s. As capitalists continually sought to preclude the ability of foreign labor to organize itself, the workplace form quickly dissolved from private schools to dispatch offices, private lessons in libraries, citizen halls, cafes everywhere. In a unique way, this foreign labor also became ‘out', dislocated, social.

To contain these new socialities arising across old geographies, the police and city planners are continuously at work. In late 2003, the already barricaded and privatized Tennoji Park in Osaka was invaded by 300 riot police who had come to evict what was known as the ‘karaoke village', a large area of the park taken over by karaoke carts, venders and crooners, gathering point for hundreds of day-workers daily who belted out song classics after work. For forty years the plaza was a hot-spot, even tourist attraction known as the ‘soul of Osaka', a musical space occupied by the downtrodden, who sunk into song and drink, dulling the pain, remembering more riotous times. In December 2003 the riot police moved in and barricaded the park for ‘construction purposes'. Vendors and crooners showed up in hundreds to watch the demolition and vent their rage. Barricades were thrown at the police, but the disobedients were quickly arrested. There would be no repeat of October 1990. All that is left of the karaoke village now is a steel fence, wrapping a completely empty lot. The park is silent.

Osaka city now plans a wave of evictions of squatters from parks all over its map. The first of the year is already underway in mid-city, and the park's residents are crouched down, preparing to resist the riot squads. The proletarians of Osaka's wards must learn the lessons of the past: against the brutal technological barricades of the riot police, surveillance and containment, they must adapt an improvised, mobile capability. The riots around Clichy-sous-bois provide a possible source of inspiration, totally mobile, skirmish-based attack, no commitments, no demands as such. No gathering points and thus no encirclement, no containment. Also in question is how social space can be re-worked and decelerated, how an autonomous space can develop against the crushing weight of capitalism, while simultaneously understanding its own limitations, how we might ‘help ourselves' to a future that doubtlessly awaits us if we seek it.[8] The strange new crisis-ridden social geographies of post-fordist capitalism offer gates for the fleeing proletariat, which now finds itself everywhere.

[1] It was revealed earlier that week that the police chief in Nishinari had been taking bribes from Yakuza gangs for a variety of ‘favors'.

[2] Except for the Yakuza gangs who had all run away from the scene.

[3] The information sharing grid between media, yakuza and government is well known in most parts of the islands.

[4] Some of these older workers had cut their teeth on the anti-Yakuza struggles of the 1980s in Tokyo's Sanya district, some who were ex-members of militant groups like the red army, some who had served prison time for throwing bombs at police in the 60s. Incidentally, the Kamagasaki revolt was a big inspiration for Otomo Katsuhiro's Akira.

[5] NGO workers can now be seen every day on the winding employment lines, monitoring workers with friendly armbands that say ‘safety patrol'!

[6] Some hut plots in the autonomous parks have gorgeous gardens growing in them, in one case an occupant had improvised a permaculture system, with over-arching grape vines shading greens below and tomatoes flanking.

[7] Many factory jobs were also shipped to East Asia at this time.

[8] One phenomenon that may offer inspiration on this point: in Tennoji park, the same park that has been fenced and barricaded, robbed of most autonomy, two homeless men living in the lower part of the park have set out before their home five comfortable leather chairs, apparently open to anyone to sit in, chat or play go. The path on which these men live and on which their chairs are situated is a vital walking path for commuters, who everyday gaze curiously or longingly at these lounging non-workers, these jesters of the free community.

Comments