An article on the history of rent strikes, written by Isaac Rose and Siobhan Donnachie for Greater Manchester Housing Action.

Last Friday, over fifty Dorchester Court residents staged a protest outside their millionaire landlord’s offices in Waterloo, demanding: no evictions, essential repairs and rent reductions. Their action, which has been accompanied by collective rent strikes during the pandemic, is part of a wave of mobilisations globally that have been marked by a resurgence of the rent strike tactic. In Britain, this follows a revival of rent strikes in recent years, most notably in student housing. This upsurge is significant because over the previous 40 years the tactic of the rent strike had all but disappeared in the fight for decent housing.

This piece will situate the recent growth of interest in rent strikes within a broader history, both in Britain and elsewhere. We will consider in detail the London Renters’ Union ‘Can’t Pay Won’t Pay’ campaign, by critically comparing it to other rent strikes. Above all, we will ask — what are the potentials and limitations of the rent strike, particularly in the context of increased atomisation of the private rented sector and the narrowing of security of tenure since the 1988 Housing Act. Can the rent strike be a collective bargaining tool for renters as we move forward into what is likely to be a prolonged economic recession induced by the pandemic? And if not, what should our strategy as a housing movement be?

*

To date the largest rent strike in British history is the Glasgow Rent Strike of 1915. The recent centenary has led to a greater appreciation and awareness of the significance of this moment, and it is worth retouching upon a few details here.

Led by the Glasgow Women's Housing Association, the 1915 Rent Strike saw 20,000 tenants withhold their rent from their private landlords, in response to a rent hike. At that time 88 percent of total housing provision in Britain was met by the private rented sector, putting working people at the mercy of unscrupulous landlords. The central pillar of the rent strike lay in Govan, the shipbuilding district on the banks of the Clyde. There, the woman’s housing committee led by the previously unknown Mary Barbour, organised constant propaganda meetings (including factory gate meetings), rent strikes and physical resistance to evictions.

Defending our Homes Against Landlord Tyranny — The Glasgow Rent Strike (1915)

The strike was not a spontaneous uprising, but rather the outcome of years of organising both by tenants and the wider trade union movement. It came at a time of rising industrial militancy and widespread class consciousness. Renters and workers knew themselves to be in a clear antagonism with their landlords and bosses. The rent strike forms only part of a much broader story of working class radicalism in the early decades of the 20th century, which would reach a dramatic peak in January 1919 when the British Government would bring tanks onto the streets of Glasgow to suppress revolt.

Nor was militant tenant action confined to the Clyde alone — similar actions broke out in Northampton, Birmingham, areas of London and in Birkenhead; where two thousand women marched on the town hall, carrying aloft banners proclaiming: “Father is fighting in Flanders, We are fighting the landlords here.” Indeed, the actions that sprang up in Britain were part of a global wave of rent strikes, which by this period had, as Mike Davis has argued, ‘become a familiar weapon in the class arsenal.’ Wherever you look you find rent strikes led by militants — socialists in New York and Vienna, syndicalists in Paris and Glasgow, and anarchists in Barcelona and Buenos Aires.

The strikes spooked the British government, heavily conscious of their damaging effect on the war effort. It acquiesced to the tenants’ demands. Legislation was swiftly passed in 1915 with the Increase of Rent and Mortgage Interest (War Restrictions) Act 1915, which brought into effect rent controls. While the government had hoped for this legislation to be temporary — a response to wartime emergency — the militancy from the tenants of Glasgow and elsewhere that continued into the 1920s, signified by a number of further rent strikes, made it impossible for this legislation to be repealed. Rent controls would remain a part of the British housing settlement until the 1988 Housing Act. Of similar significance to the creation of rent controls were the reforms passed by the Housing and Town Planning Act 1919 (the ‘Addison Act’) which made state provision of housing a right for the first time in history.

A Still from 'Tenants In Revolt', a short film that depicts the Stepney Tenants Defence League out on rent strike (1939)

Throughout the ‘20s and ‘30s, rent strikes continued to be deployed as a means of working class mobilisation over housing — perhaps most notably by the militant Stepney Tenant Defence League in the 1930s, one of whose leaders, Phil Piratin, would go on to become the Communist MP for Mile End in the 1945 election. The simmering class conflict and renter organisation was a significant factor in pushing the government to begin constructing council housing — which would set a blueprint for the mass housebuilding programmes of the reformist governments after the second world war. It is no exaggeration to say that it was out of the prolonged social struggle over rents, instigated by the dramatic strike of 1915 in Glasgow and continued in the decades hence, that the social democratic housing settlement that would predominate throughout most of the second half of the 20th century was won.

*

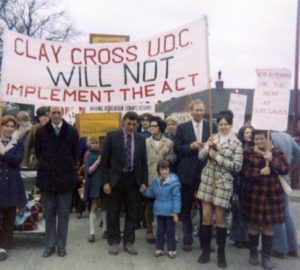

In the immediate postwar era, the rent strike went into abeyance. Good quality council housing, built to the exacting specifications of Nye Bevan’s vision, resolved the housing question, at least temporarily. Yet by the 1960s, the rent strike had returned within the context of a broader wave of working class militancy, in response to increasing attacks on the social democratic settlement by the right. The period from the ‘60s onwards saw a number of significant rent strikes by council tenants, including in St. Pancras, London (1959–1961); East London (1968–1970); Kirkby, Merseyside (1972–1973); and Clay Cross, Derbyshire (1972-3). These strikes were all in response to the hiking of rents by Tory administrations, whether in local government in the case of the two London strikes, or by the Heath government’s Housing Finance Act in the case of the latter two. It is worth noting that the rent strikes of the middle decades of the 20th century were unlike the strikes of Glasgow in that they were by council tenants, not against private landlords but against local authorities and the government.

Clay Cross, Derbyshire, resisted the Heath Government’s Housing Finance Act, which sought to hike rents across council housing (1973)

The political contestation of the 1970s ended with the decisive victory of the right and organised capital. This had an enduring impact on the housing settlement, the consequences of which we live with today. Thatcher’s victory in ‘79 paved the way for the Right to Buy legislation of 1980, perhaps the most significant privatisation in British history. After winning a second election in ‘83 and defeating her staunchest opposition, the NUM, in ‘84; Thatcher further reshaped housing with the 1988 Housing Act.

The 1988 Housing Act is the most significant piece of legislation governing today’s housing settlement. Above all else, this Act lies at the heart of the current precarity of renters. It created the legal form of the ‘assured shorthold tenancy’, today the default category of tenancy in England and Wales. These tenancies have limited security of tenure — a mandatory minimum tenure of 6 months which is the shortest in Europe. It also introduced various grounds for eviction, including Section 8, which makes rent arrears a mandatory ground for eviction (i.e. no discretion for mitigating circumstance, e.g. loss of income); and perhaps most significantly Section 21, the ‘no fault’ eviction, which allows a landlord to evict a tenant without any reason. The 1988 Act, and the precarity that it threw renters into, was a crucial condition for the rapid expansion of buy-to-let mortgages. Finally, the Act also stands as a bookend to the period ushered in by the 1915 Glasgow Rent Strike, as it was this legislation that repealed rent controls, the strike’s most significant victory.

In this new context, the conditions which were the bedrock of the strikes of the ‘60s and ‘70s no longer held. The selling off of council housing destroyed the communal basis for organised rent strikes against a single landlord, as well as dramatically expanding homeownership. Tenants in the private rented sector in contract largely held an individual, atomised relationship with a mosaic of small-time landlords. Similarly, the conditions that were essential for the tenants movements of the early 20th century — a organised and militant working class movement — no longer held either, having just been dealt a historic defeat. Above all, Thatcher’s forging of a new housing settlement set the grounds for a private rented sector that would be characterised above all by a profound precarity on the part of tenants — who live under the shadow of an entire legal edifice designed to work in the interests of landlords. The extremely unequal legal dynamic that developed led to a significant weakening of the ability of tenants to organise, defend and collectively support one another.

*

In the neoliberal era, there has been an almost total disappearance of rent strikes in Britain, until recent times. Successive governments continued to propel forward Thatcher's vision of a ‘property owning democracy’. Policy reflected the dominant belief — that homeownership represents the only feasible way to obtain decent housing. The focus on homeownership was designed to erase the potential for opposition by holding out for the possibility of a ‘stake in the system’. And if the carrot didn’t work, the stick would — debt, in the form of mortgages, hung over homeowners and acted a powerful disincentive to strike action in the workplace. This was a conscious move to minimise labour disruption and working class organisation.

Yet two key trends have served to disrupt this terrain and have re-ignited the housing struggle. First, is that since the mid ‘00s, the growth of homeownership stalled and went into reverse, most notably among the working population. In the absence of public housing, the private rented sector has returned, and millions now are trapped within an unequal and oppressive system. Although private renting was envisaged by neoliberal ideologues as merely a stop-gap before people ‘got on the housing ladder’, the reality is that without council housing, the private rented sector would never solely perform this function, and the sector would grow. And over the last two decades it has grown, dramatically, now representing around 20% of housing by tenure type across the country — though in some regions, e.g. London and the other major cities, this proportion is far higher.

The result is that there is now a sharp class antagonism experienced by millions, between renter and landlord. In the worst cases, landlords are abusive, negligent and vindictive; and even in the best case, with a so-called ‘good landlord’, the reality is that this system remains exploitative. The depredations and humiliations meted out by landlords to their tenants has been the primary drive behind the growth in tenant unions in recent years, such as ACORN, the London Renters Union and Living Rent.

The second key trend is the financialisation of housing and urban space. This process has seen housing shift from being primarily about its use value (as homes for people) to its exchange value (as an asset for landlords, developers and finance). Raquel Ronik has shown how the seizure of rental markets by global finance has become a mechanism for rent extraction and wealth accumulation. In the UK this dynamic has been most extreme in London, where international financial flows have reshaped access to housing, driving gentrification and displacement; yet it is by no means confined to the capital. Manchester too is being reshaped by this process, as GMHA has documented over the past three years. Financialisation has had an upward pressure on rents and growth in build-to-rent models.

The Barcelona PAH take their protest to the global headquarters of Blackstone in New York (2018)

In other countries, for example Spain, the role of financial actors in housing is more developed, and we witness the rise of ‘global corporate landlords’. Large wealth funds, such as Blackstone, a private equity firm, have entered the housing market directly. They have bought up rental property and let it out to tenants, often buying when house prices collapsed. This was in direct response to the collapse in the mortgage market after the crash. In Spain, this concentration of ownership led to a vigorous kickback from organised tenants. In contrast, in the UK the mortgage market has remained profitable, in large part due to the favourable conditions for buy-to-let landlords. A result is that the presence of global corporate landlords has not been as advanced here over the last decade as in Spain, Ireland or the USA. The economic crisis following COVID-19 may however accelerate the rise of the global corporate landlord as a major player in the UK context and this needs to be followed closely. However, one notable exception from this general picture, is student accommodation.

Student accommodation is one of the most lucrative sections of the UK property market. Universities began selling off student halls in the 1990’s and allowed developers to circumvent housing regulations that are not applicable for student accommodation. A high proportion of student accommodation is inadequate and very expensive. Militancy in student housing has developed in recent years in response, leading to the first wave of contemporary rent strikes in the UK. Most notably the ‘Cut The Rent’ group formed by UCL students, who organised a five month rent strike in 2017, winning concessions on rent and financial support totalling a £1.5 million. The success of the UCL action resulted in copycat rent strikes taking place on other uni campuses, notably at Sussex Uni where the local branch of ACORN provided key organisational capacity.

http://www.gmhousingaction.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/07/cut-the-rent-300x225.jpg

UCL Cut The Rent went on rent strike and won £1.5m in concessions from the university (2017)

In areas where financialisation of the rental market is most advanced, where capital invests in housing directly and not through the mediator of the banks and mortgage holders, we see something of a return to the key condition that enabled rent strikes in the ‘60s and ‘70s — a single landlord. Largely though, the UK rental market remains a mosaic of relatively small landlords, with renters holding an individual relationship to their landlord. Yet this sector has grown dramatically, with a lack of council housing and easy mortgage options for buy-to-let landlords. It is the growing social weight of renters that has provided the basis for the growth of tenant unions. The result of this transformation is that asset ownership has become a key faultline in the UK today. The economy has become increasingly a rentier economy. The country is organised in the interests of those who gain from this economy, and dominated politically by what Will Davies has termed a 'rentier alliance'.

*

When the COVID-19 crisis hit in March, tenants unions globally were part of a wave of organised response. In Barcelona, 16,000 households have signed up to rent strike, the details of which were covered in Benjamin Irvine’s piece Spring in Huelga. Similarly, in the USA tenant unions have transformed the inability to pay rent into a collectivised struggle demanding rent freezes, reductions and changes in housing policy. An alliance of national organisations and community leaders in the USA have been coordinating and mapping the rent strikes. As of May 1st, around 200,000 people had taken the pledge to rent strike, out of whom 31 percent said they didn’t pay rent in April. Many tenant unions and other campaigns across the USA have planned localised rent strikes — in New York alone there were an estimated 12,000 pledges to not pay rent recorded before plans for strike action on May 1st. These strike actions have led to change at a state and city level.

In the UK the housing movement also moved in response to the crisis. Tenant unions such as ACORN have been at the forefront of the response — coordinating mutual aid, campaigning for rent freezes and an eviction moratorium, and in some cases such as at Lancaster University’s student halls, organising rent strikes. The movement nationwide was able to force the suspension of section 21, and fight for the extension of this ban till mid August. In London, the London Renters Union (LRU) has seen their membership double from 2000 to 4000 members during the crisis. They have responded with a ‘Can’t Pay, Won’t Pay’ campaign (CPWP), pushing five key demands to collectively support renters in the immediate situation and fight for radical change in the long term. The demands are: suspension of rent, cancelling rent debt, permanent eviction ban, introduce rent controls and eradicate the hostile environment within housing. Since the campaign began almost 4,000 renters have pledged to join and support those resisting evictions, access support and advice and withhold rent.

LRU’s Cant Pay Won’t Pay campaign has called for rent cancellations and an evictions moratorium (2020)

The option of a general rent strike was debated within LRU. After a lengthy internal discussion, organisers reached the conclusion that striking while Section 21 stands would place their members in extremely precarious situations. CPWP, while initially conceived as a rent strike, has remained more like an online pledge and campaigning tool. Because of the fragmentation of the private rented sector, there is no mass renter subject that could mount an effective strike against a single target. In lieu of this, CPWP was positioned as a collective campaign to encourage members to prioritise essential living costs during the crisis, with LRU on hand to organise member defence to members on a case-by-case basis.

However, LRU has actively been supporting small scale rent strikes. Most notably is Dorchester Court Tenants Union (DCTU), now a branch of LRU. DCTU organised a strike of 96 tenants who are demanding essential repair work, rent reductions and no evictions for rent arrears. The tenants of Dorchester Court formed a union in November 2019 in response to inaction regarding poor conditions from their millionaire landlord. The fact that the tenants had collectivised prior to the COVID-19 crisis ensured that they were able to stage a rent strike. The tenants at Dorchester Court for the majority share the same landlord, enabling them to mitigate risk to individuals and by withholding rent collectively. Having a single landlord is a prerequisite for deploying the rent strike, and the Dorchester Court experience bears similarities to the student rent strikes in this way.

Dorchester Court Tenants Union, a branch of LRU (2020)

Amy, an organiser from LRU, believes that the crisis has strengthened the collective consciousness of renters. She hopes that this shared collectiveness has changed the perception regarding class antagonisms and racial inequalities in housing. This growing collective consciousness has led to tenant union membership growth, as people look to mutually support one another in the face of a government that prioritises the economy over human life. As well, it has not only enabled local networks of solidarity, but has begun to mount national pressure on the government. We could point to the recent organised pushback by renter groups against Labour’s policy shift under Starmer as another example of the growth of this consciousness today.

It is this rising consciousness that offers hope for the future. Looking back to the early rent strikes at the start of the 20th century, organised by tenants in the private rented sector, one thing is immediately clear — that these strikes and movements were highly conscious, led by militants who understood the world in terms of class antagonisms. This consciousness was the product of decades of working class organisation. In order for the clarifying moment of our times to have legacy beyond the immediate crisis, the patient and steady work of organisation will be key. We must avoid the situation when the lockdown ends and a form of ‘normality’ resumes, that the upsurge in militancy dissolves. We must see the corona crisis for what it is: not a decisive shift in the balance of forces but one, significant, step upon a far longer road to building power from below.

*

The history of tenants’ struggles in Britain provides many examples of rent strikes. Rent strikes have been at their most powerful when they have emerged from high levels of organisation and a confident militancy by tenants. Through withholding rent and challenging landlords, housing struggles have been a crucial component of broader working class struggle. In the last decade, housing has returned as a major political question. The growth of the private rented sector and the financialisation of urban space has created a sharp class antagonism between those who need housing as homes, and those who utilise it as assets. It is out of this context that the contemporary housing movement has grown — resisting estate demolition, and collectivising renter struggles through tenant unions.

However, thus far rent strikes have only had a limited role within the revived housing movement. The notable exceptions have been in student housing, and in those places with a single landlord — Dorchester Court being an example. These strikes recall those of the ‘60s and ‘70s, where tenants were united in opposition to a single landlord. However, in many ways, the wider picture of today’s private rented sector recalls that of the early 20th century, with little security and limited rights for tenants. Yet what is missing now is a level of organisation, militancy and class consciousness that characterised the great rent strikes of 1915 and after.

The crisis brought about by COVID-19 has unveiled the divide between landlords and tenants, and contributed to growing levels of organisation and militancy among tenants unions. The moment has been an opportunity seized by tenant unions, all who have seen an increase in membership and activity during this period. However, far greater troubles lie ahead of us. Over the course of the pandemic, almost half a million have now fallen into rent arrears, and are now at risk of eviction. Many can’t pay — and shouldn’t pay. The likelihood of a prolonged depression is high, with the spectre of mass unemployment looming on the horizon. When the government lifts the eviction ban at the end of August, we can expect a wave of evictions, potentially up to 230,000 at risk of losing their homes.

Additionally, the longer term dynamics at play could lead to a concentration of asset ownership by the rentier class. Banks are currently pulling back lending to first time buyers and those with limited capital — which will price more out of homeownership, and could drive small landlords out of the market. Some landlords may be forced into sales, as they enter financial distress. This, combined with falling house prices means that for those with access to large amounts of capital, purchasing housing while the market is low, with the intention to rent it out, could be an attractive investment opportunity. An outcome of the crisis may well also be the acceleration of financialisation in the housing market — with investors and global corporate landlords moving to build-to-rent.

ACORN Manchester have been at the forefront of mobilisations in the city to defend renters in the face of the crisis (2020)

The organised renters movement’s next steps are clear. First, we must be emphatic: we will resist evictions by any means necessary. Protecting people at risk of eviction from the fallout of the crisis has to be the highest priority. This priority implies a tenant union organising model that puts the difficult work of member defence at its heart, as well as the organisation of anti-eviction teams to physically block evictions where necessary.

Second, in the medium term, the tenant unions must maintain their growth, working to amass a greater social weight over the coming years. There are no shortcuts to building power — this will require organisation, fighting and winning cases, and continuing to collectivise the struggle against landlords. It will also require that tenant unions become embedded presences in working class communities, defending members against landlords, but also looking to become hubs of community strength and pride. As well, tenant unions must work to build links with other institutions of the organised working class, most importantly the trade unions. Earlier in July ACORN and Unite the Union signed a recognition agreement, which is a hugely positive move. Bonds of solidarity like this must be built not just at the top of the organisations but at every level, right down to the base.

Third, the movement should map ownership. Portfolio landlords and corporate landlords in the build-to-rent sector should be targeted as a priority. The collectivisation of tenants under one landlord provides an opening to rent strikes and other decisive actions which can act as test cases to advance the renters struggle as a whole.

Finally, we must not neglect the government as a target. The government must be forced to stick to their promise to abolish Section 21 and we must extend our demands to include reforms to Section 8, particularly so that rent arrears become a discretionary not mandatory ground for eviction. Winning these two crucial changes to the 1988 Act would, by removing immediate legalised precarity for renters, grant renters more space to organise — a ‘non reformist reform’ that could open up further terrain in the struggle against landlords. Our demands on government must advance, to the crucial calls for rent controls and public housing.

‘Pay No Rent’ — a still from 'Tenants in Revolt'. The renter struggle before the second world war can serve as an inspiration and guide to us today.

The current crisis has been an opportunity seized by the housing movement to organise precarious renters. It has provided stark evidence of whose side the government is on, and it has laid bare the injustices at the heart of our housing system. Yet, rather than this being a decisive moment, comparing current activity against the historical record demonstrates the distance yet to be travelled if today’s renter movement is to reach past heights. Above all the renters movement must — like our forebears in the Glasgow Women's Housing Association or the Stepney Tenant Defence League — raise our horizon from simply defending tenants against individual landlords, to a fundamentally transformed housing settlement and society.

Organisation, agitation and political education will be key, and a justified sense of militancy in the face of landlords and their lobby. The fundamental dynamic underpinning the politics of housing in Britain today is not going away. Renters must organise themselves — and for those seeking transformative social change, renters unions and the fight for housing is certain to be a key battlefield in the years to come.

Acknowledgements: The authors would like to thank Jacob Murkherjee and Joe Billsborough for their helpful comments on earlier drafts of the piece, and Amy Smith for agreeing to be interviewed.

This piece is third in a three part series published by GMHA exploring the impact of the current crisis on housing struggles. You can read part 1 on Spain’s rent strikes here, and part 2 on the financialisation of Berlin’s urban space here.

Isaac Rose and Siobhan Donnachie are co-ordinators of Greater Manchester Housing Action.

Comments