Does the failure to reach an agreement to keep global temperature rises below 2 degrees celsius prove that capitalism has no answer to man-made climate change?

The COP-17 climate change talks in Durban earlier this month agreed to a binding greenhouse gas emissions agreement to be prepared by 2015 and entering into force in 2020.1 At least, that was the headline. In practice, the world's states agreed to enter discussions towards an agreement, and that could be sabotaged by any of the major players pulling out at any time.

There is widespread scientific consensus that to avoid dangerous, run away climate change, temperature rises will have to be kept to 2oC above pre-industrial levels. This was acknowledged in the Copenhagen Accord at the COP-15 summit in 2009 (which was issued after parties failed to reach a formal agreement). The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change SRREN report states that this "implies that global emissions of CO2 will need to decrease by 50 to 85% below 2000 levels by 2050 and begin to decrease (instead of continuing their current increase) no later than 2015." Clearly, as the deal agreed at Durban, even in the best case scenario, will not even be drafted until 2015, this is not going to happen.

The world is currently on course for temperature rises of 4oC or more on pre-industrial levels by the end of the century. And as the BBC points out, "that's an average; some places could see twice that." This is a problem. It not only means the localised effects of climate change on crops and ecosystems will be severe, it means positive feedback effects are likely to kick in, accelerating the rise of global temperatures. This is already happening. The Independent reports that:

Dramatic and unprecedented plumes of methane – a greenhouse gas 20 times more potent than carbon dioxide – have been seen bubbling to the surface of the Arctic Ocean by scientists undertaking an extensive survey of the region. The scale and volume of the methane release has astonished the head of the Russian research team who has been surveying the seabed of the East Siberian Arctic Shelf off northern Russia for nearly 20 years.

Blogger Adam Ramsey has suggested this could be 'the world's scariest news', since similar releases are suspected in the Permian-Triassic mass extinction, the "mother of all mass extinctions." So to put it mildly, the worst case scenario is pretty bad.

The obvious libertarian communist answer here is to point out that the endless economic growth required by capitalism is incompatible with finite ecological limits. This is certainly a powerful argument. One of the most detailed elaborations of this is the theory of the ecological rift, which holds that the problem is inherent to the very process of capital accumulation, and thus no solutions to climate change can be found without getting rid of capitalism.

Due to capitalism's inherent expansionary tendencies, technological development serves to escalate commodity production, which necessitates the burning of fossil fuels to power the machinery of production. (...) The theory of the metabolic rift reveals how capital contributes to the systematic degradation of the biosphere.

I am sympathetic to this argument. But I also worry that this under-estimates the flexibility of the capitalist system. In many ways, this relates to the argument about the possibility of reform (1, 2). So I'm going to play devil's advocate and explore the possibility of a capitalist solution. So, to start with, while it's true that "historically, economic development has been strongly correlated with increasing energy use and growth of greenhouse gas emissions", the IPCC argue that "renewable energy can help decouple that correlation". In other words, while the theorists of the ecological rift argue expanded commodity production requires burning fossil fuels, this isn't strictly true. It merely requires energy. Could this come from renewables?

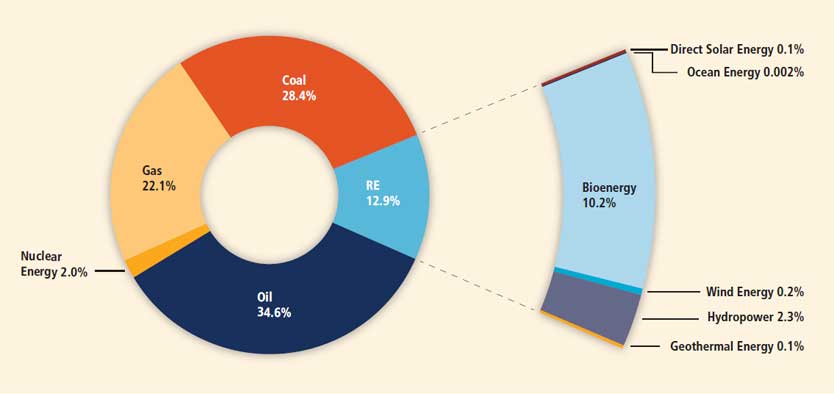

The headlines certainly suggest so. "Renewable energy can power the world, says landmark IPCC study". The report itself is somewhat more modest. As of 2008, just 12.9% of the world's energy mix came from renewables. Of that, 10.2% was bioenergy (i.e. mostly burning wood, which may or may not be sustainably grown). Of the rest, 2.3% is hydropower, with the remaining 0.4% being made up of wind (0.2%), direct solar (0.1%), geothermal (0.1%) and ocean energy (0.002%). See chart below (from the IPCC SRREN report - click to see full size).

The IPCC's scenario-based report found that "more than half of the scenarios show a contribution from renewable energy in excess of a 17% share of primary energy supply in 2030 rising to more than 27% in 2050. The scenarios with the highest renewable energy shares reach approximately 43% in 2030 and 77% in 2050." So not quite the headline 'renewables can power the world', but certainly lots of scope for expansion. And there's nothing anti-capitalist about this. Renewables are potentially big business. While BP recently sold its solar division, which perhaps strengthens fears of greenwash, there's potentially lots of money to be made in renewables. An interesting project is the Trans-Mediterranean Renewable Energy Cooperation (TREC), which is lobbying for solar fields in the Sahara desert to power Europe via High Voltage DC (HVDC) cables, a relatively new invention which allow electricity to be transmitted long distances for acceptable wastage.2

The problem they have is it's not quite competitive with fossil fuels. Which brings us back to the absence of a binding global agreement to reduce emissions. As the IPCC say:

Climate policies (carbon taxes, emissions trading or regulatory policies) decrease the relative costs of low-carbon technologies compared to carbon-intensive technologies. It is questionable, however, whether climate policies (e.g., carbon pricing) alone are capable of promoting renewable energy at sufficient levels to meet the broader environmental, economic and social objectives related to renewable energy.

They also say that direct state investment is needed. Both of these things are unlikely in the absence of a binding global agreement, and go against the flow of 30 years of neoliberal re-regulation. And while this is currently a distant prospect, there are significant capitalist interests pushing for it. The EU have taken this line at recent COP negotiations (having outsourced emissions-intensive production to China, India, Brazil etc, of course). As have numerous corporate lobby groups like We can lead or the Corporate Leaders Group on Climate Change. While China has been pursuing a very dirty industrialisation, it has also started to legislate on emissions and has become the leading producer of several key renewable technologies (solar panels and wind turbines, iirc). A binding global agreement would create a massive export market. So perhaps a deal by 2015 isn't as remote as it looks at first glance. As the 'We can lead' group put it:

We Can Lead is a nationwide coalition of more than 1,000 business leaders - innovators, entrepreneurs, investors, manufacturers and energy providers - who support comprehensive, forward-looking energy and climate policies in the United States which will catalyze and grow a portfolio of new and existing energy sources, create new American jobs and end our boom/bust energy cycles. The network includes small and medium sized companies to large-scale energy providers, Fortune 500 companies and leading consumer-facing brands. Sound energy policies are our best hope towards reclaiming America's competitive mantle as a leader in this next wave of economic growth - while working on climate stability and energy security. Now is the time for action.

Currently these voices are out in the cold. But so was Keynes before the depression, and the Chicago School before the breakdown of the Keynesian regime in the early 1970s. FT editor Martin Wolf has already pointed out we're in Britain's longest depression since WWI, "likely to generate a bigger cumulative loss of output than the “great depression”". And that's before the now likely double-dip recession kicks in. If economic stagnation prevails, those voices in the wilderness could be brought in from the cold like those before them. But we shouldn't get too excited. For one thing, a rise in energy costs (e.g. through carbon pricing), all other things being equal, will drive inflation, and especially food inflation. That means falling living standards. The price of a capitalist solution to climate change could be mass famine in large parts of the world.3 So we should certainly err on the side of communism, but I think it underestimates the flexibility of capitalism to think there can be no moves towards addressing climate change, even if they're too little, too late.

- 1'COP' = 'Conference Of the Parties' to the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC). The Kyoto Protocol was a protocol under the UNFCCC, and the annual COP talks are appended with the number to signify how many there have been. So the COP-17 in Durban was the 17th conference of the parties to the UNFCCC.

- 2This adds an interesting twist to the strategic significance of north Africa, in light of recent events.

- 3A focus on climate change also ignores numerous other ecological boundaries.

Comments

That 'ecological rift' stuff

That 'ecological rift' stuff I wanna read more on. I like Clark, York & Foster's little marxist take on science and ecology niche at the moment. I read their books on Stephen Jay Gould and Intelligent Design and have wanted to check our Ecological Rift for a while. Anyone read it?

As far as the argument, I think you're right that they may underestimate capitalism's dynamism. I recall a thread about this very subject 3-4yrs ago where the competing voices were similar but the voice recognising and not writing off a capitalist solution was drowned out by the hysteria of ARE YOU SAYING CAPITALISM CAN SAVE THE ENVIRONMENT?

When in fact what was said, as you've repeated, was that capitalism may find some mechanism to reduce global temperatures but it will be on the terms of capitalists and likely be with massive social costs - we know who will bear the brunt of that. No free lunch eh?

I've read chapters from 'the

I've read chapters from 'the ecological rift' but not the whole thing. i'm basically sympathetic to the argument, but I do think they overstate it a little. I think they claim environmental destruction is the second 'absolute general law of capitalism' alongside accumulation. while there's certainly strong tendencies to ecocide, it doesn't seem inconceivable that you can get environmental protection and still have accumulation. whether that will happen or not is another question, and i'm pessimistic. it happens on a local scale all the time though, e.g. environmental protests in China forcing tightening of pollution etc.

Bellamy Foster et al build on James O'Connor's 'second contradiction', a classic Marxist ecology text which argues that alongside the first contradiction (between the relations and forces of production, i.e. the class struggle), there's a second contradiction between the forces and relations of production together, and the 'conditions of production' i.e the natural (and i think social) environment. Iirc O'Connor saw the workers movement as the agent fighting the first contradiction, and 'new social movements' as the agent fighting the second.

sorry was just editing my

sorry was just editing my post as you replied!

Joseph Kay wrote: there's a

Joseph Kay

That second seems similar to Harvey's 'relation to nature' as one of his 'seven activity spheres' in Enigma of Capital. I think Harvey seems the new social movements playing a similar role too.

Yeah, I agree with Joseph's

Yeah, I agree with Joseph's comments here.

While the issue of climate change is something which is much more urgent than the way it is being dealt with (or not as the case may be) I agree that theoretically it is something which could be solved in a capitalist society.

As can be seen from the types saying "reform is impossible", many radicals and revolutionaries have a millenarian sort of apocalyptic approach, where they think everything is going to come crashing down at some point - but of course this has been prophesied for hundreds of years and has yet to materialise…

This didn't really fit in

This didn't really fit in anywhere in the blog, but Corporate Watch have done an excellent critical guide to climate change technologies (if you ignore the odd bit of somewhat liberal editorialising). Even if you're in the 'we need a revolution' camp, we still need to think about this stuff since if we overthrew capitalism tomorrow one of the first tasks for the workers councils would be a massive shift from fossil fuels to renewables, district heating schemes, public mass transit and so on, or we'd still end up with dangerous climate change.

will have a wee jook at that

will have a wee jook at that

Climate Capitalism by Peter

Climate Capitalism by Peter Newell and Matthew Paterson is also an interesting read, makes a pragmatic case for capitalist solutions to climate change. Argues specifically for going with the flow of existing power in neoliberal capitalism, making sure finance capital has lots of profits to make, bringing them along. I suspect it's a bit too optimistic, but definitely worth the read if you're interested in this stuff.

Quote: In other words, while

I'm not certain this is true - at least in theory, expanding commodity production is compatible with even reducing energy use. For starters, when it comes to industry more energy intensive doesn't necessarily mean more productive. But more fundamentally, there's a difference between expanding commodity production in general, in terms of expanding value, and expanding the production of particular commodities quantitatively in terms of making more toasters, cars, iPhones or whatever.

It seems to me the basic problem with theories like the theory of the ecological rift, which see capitalist accumulation as fundamentally incompatible with ecology, is they make the classic error of confusing social relations for things. Capitalism must expand endlessly, but what it must expand is profits, which are a social phenomenon rather than real things; value not use values. In some cases it can actually be in capitalists' interests to produce less in order to make more money. And capitalists can switch from investing in things which cost a lot of energy e.g. manufacturing cars to things which have lower energy costs but are still profitable e.g. selling adverts on social networking sites.

Of course in practice the development of capitalist industry *has* meant increasing energy demands, but I don't think this is necessarily a universal principle.

~J.

jolasmo wrote: I'm not

jolasmo

yes this is true, and commodities can be immaterial (services, software) which require much less energy to mass produce than tangible ones. that said, up until now there has been a very strong correlation between economic growth and energy consumption. and yes, I think this is where the 'ecological rift' thesis overstates its case: it describes actually existing capitalism, but that doesn't mean it applies to all possible capitalisms. still, time is running out for that to materialise!

Steven. wrote: While the

Steven.

I wonder if this is one of these cases where capitalism needs a 'push' to act in its own long term interests. Question is, what would that push be? I can't see a global ecological movement emerging to sufficient strength in the incredibly short timescale available. The class struggle might do it, but there's no reason that should push things in a green direction, and the cost of a transition away from fossil fuels may well mean 'green austerity' measures. I guess what I'm hinting at in the blog is it might emerge from within the capitalist/state system itself, as oil prices rise and interests shift, massive investment in a transition away from fossil fuels might start looking like the solution to economic depression, and a 'green arms race' might provide a channel for emerging US-China rivalry to follow a non-military course... All speculation of course. And unjustifiably optimistic tbh.

I broadly agree with Joseph

I broadly agree with Joseph on the possibility of an ecological movement emerging to 'push' capitalism in the right direction. As someone who's come out of the people and planet/green party/activist circle we went nowhere. The combined attempts at summit hopping protests, lobbying and parliamentary politics haven't come close to shifting capitalism and there doesn't seem to be much vision of what to do next other than more of the same.

There's been very little link up between activists and working class struggle, with one or two exceptions (Vestas perhaps). Trade unions have made token moves in terms of environment reps etc. but again this isn't anything like a concerted class struggle to impose a real engagement with the necessity of climate change.

I think it's possible, though I'd certainly not suggest we should rely on it, that we'll see some form of mass movement from the global South in response to climate change. There have been some signs of that so far, and it is where we should expect to see the worst effects of whatever climate change does occur, so that may concentrate minds in a way that doesn't happen here.

I think the shift from within capitalism, frankly, is the best we can hope for though (barring a sudden collapse in capitalism for some other reason in the meantime/revolution predicated on some other struggle). There are growing numbers of people talking about how capitalism could be reformed to deal with the problem, and with numbers that seem to make some sense both economically and environmentally: Jonathon Porritt, Amory Lovins, Philippe Legrain,... Desertec, for example, as mentioned, has huge potential and some pretty serious backers now: Munich Re, PWC, etc.

I suspect any global capitalist solution will involve quite a lot of nuclear power, will see costs in energy and food passed on and resulting shortages in parts of the world and some form of expanded carbon trading (with associated derivatives and therefore potential for accumulation) possibly at both international and domestic levels.

I have to say I don't really buy the idea that capitalism is inherently incapable of dealing with the problem at all, though it does make a nice argument against capitalist realism I've found. You just have to be careful it doesn't descend into some kind of deep green/de-growth/primitivist/anti-civilisation thought instead.

great blog post btw

great blog post btw

This is a great blog post,

This is a great blog post, informative, unnerving, and thought provoking. I agree with the skepticism Joseph has over the stuff about how capitalism is inherently ecocidal. I think that kind of thing is partly about people wanting theoretical predictive answers when it seems to me that what actually happens is historical and very much up in the air (it's under-determined, so to speak). I think it's possible that the collective institutional stupidity within the current arrangement of capitalism has too much power and momentum that change won't happen in time to avert ecological catastrophe and I find Joseph convincing when he says that the worst case scenario is a really bad one. Joseph, could you say a bit more on that worst case scenario in terms of the potential for disrupting human societies massively? It seems to me that if things get bad enough in terms of the consequences of ecological damage it could help enough capitalists to change their minds and move in a different direction toward a greener capitalism. And really eco-catastrophe could provide a growth market for the industries of catastrophe and aftermath management as well as for the various things needed in rebuilding. That may not happen, and it may not happen fast enough to avert really awful and irreversible climate change, but the outcomes here aren't predetermined within capitalism. Different capitalisms are possible within the framework of capitalist social relations.

I don't know how to put this clearly but I do think there's like a magnified risk because of the massive technological forces that exist. It's like with nukes - I think that people in charge are dumb/evil enough to actually use then, that's a real threat, and there systemic tendencies that predictably produce that kind of evil and stupidity. Likewise with ecological crisis, it's a real possibility and some of the correctives that are tied to biotechnology (I'm thinking of efforts to create micro-organisms that eat pollutants etc - I recently listend to this radio program http://www.radiolab.org/2008/apr/07/ where they talked about bio-engineering and it was kind of unnerving to hear people talk about this kind of work as just a matter of tools). I think aspects of capitalism encourage a reduction of moral and political problems to administrative and technical problems, which encourages large scale mistakes and negative consequences. But it's possible that capitalism can solve the problems it generates, solve them on its own terms in a way that maintains the core problems of exploitation and hierarchy and so on and which makes further future problems likely. We don't know if those problems will necessarily end capitalism or if they will get solved or not, because those outcomes are historical and contingent.

Nate wrote: Joseph, could you

Nate

Well, as far as I can tell above 2 degrees it quickly becomes a bit of an unknown, with all sorts of positive feedback effects. Worst case is a mass extinction on a par with the Permian-Triassic one (as indicated in the blog). Homo sapiens are a pretty resilient and adaptable species, so i'd guess it wouldn't be the end of human life, but a pretty dramatic collapse of civilisation, agriculture etc... Apocalyptic stuff. In terms of what state planners are thinking about, the UK government commissioned Stern report says the following for developing countries:

Stern

And for developed countries:

Stern

So, generally pretty grim.

Thanks Joseph. Yeah, very

Thanks Joseph. Yeah, very grim. But not "end of human society" or "total social breakdown" grim, meaning that capitalism could persist through all of this and the very wealthy could probly count on being insulated from most of it. So maybe they'll further fuck the rest of us and our descendents. Ugh.

Yeah, more likely than

Yeah, more likely than 'collapse of civilisation' type scenarios is a big increase in droughts, famines and displacement/refugees, a subsequent increase in inter-state conflict over scarce resources (particularly water, but also remaining fossil fuels and new sources e.g. desert solar farms). That would probably mean a general militarisation of society, greater control of borders etc. More 'Children of Men' than 'Lord of the Flies'. But still capitalism, yeah, and plenty of scope for the wealthy to move inland, build gated communities, cope with rampant food inflation etc.

Joseph Kay wrote: This didn't

Joseph Kay

I agree, but how would you respond to someone who pointed out that communism might actually put more strain on the environment by lifting billions out of poverty and allowing them to consume many more goods? Seems to me (as I argued in this thread) that we might also have to voluntarily reduce our own population to reduce strain on the earth's resources. I recognize this is a controversial position, but it seems to me the cessation of poverty might balance out or even be a greater strain on resources than that eliminated by the expropriation of the rich and the reduction in production of luxury items. As I understand it alternative energy sources could not immediately replace fossil fuels, it would take a long time to replace the current infrastructure with cleaner technologies, so I think a purely "technological solution" to this problem is not feasible...

tastybrain wrote: I agree,

tastybrain

Don't ask me, ask all the sweatshop workers in the workshops of the world who spend 18 hour shifts making consumer goods. I don't suspect they'll be overthrowing capitalism then resolving to ramp up output! I think in any hypothetical communist movement superseding capitalism, economic output is likely to collapse, not least with strike waves, factory burnings, armed conflicts etc. And economic collapse is good for the climate (note, economic collapse i.e. value isn't the same as a collapse in wealth i.e. use-values, so despite economic collapse i'd imagine there'd be an immediate bump in living standards for the majority - less work and more stuff).

I'd imagine the 'communisation' of society will be a very immediate necessity of securing food supplies and enough bullets to squash counter-revolutions. I doubt plasma TVs for everyone will be very high up the agenda.

I think there'd likely be widespread abandoning of workplaces (think of the death-trap Chinese coal mines that are driving CO2 emissions growth), and once basic necessities were being met and the threat of counter-revolution receded, there'd be a conversation about levelling living standards, launching massive public works schemes to bring clean energy to everyone, and the gadgets that are powered by it, maybe re-commencing production of consumer goods and the like, if the conditions of production could be sufficiently humanised for people to undertake it voluntarily.

But tbh, I don't really find this a useful line of argument. It's impossible to imagine what a hypothetical communist revolution might look like, and how it will relate to ecological issues. I think what's far more likely, given the balance of global class forces, is some form of woefully inadequate capitalist 'solution' (as outlined in my repsonse to Nate above). As i think that's much more likely than global communism in the next couple of decades, it seems like it's more worth thinking about, especially as in many ways it's already in motion.

James Lovelock of "Gaia" fame

James Lovelock of "Gaia" fame wrote a book a few years ago outlining the worst case global warming scenario: 6 degree temperature rise by 2100 with the last 200 million humans being able to live only along the arctic and antarctic coasts.

I guess I should say here

I guess I should say here that I am thinking of a time when the immediate struggle against the capitalists is more or less over and production is being re-organized. Obviously during the revolution itself we will have more pressing concerns than ecological problems.

Joseph Kay

No, of course not. But all of the labor doesn't have to be done by those people (who may never want to work in production again...). What about the formerly unemployed, those who were in unproductive jobs like advertizing and insurance, expropriated bourgeois, and so forth. Presumably, if they themselves are reaping the full benefit, people may be willing to continue to produce more or less necessary consumer goods, usually with the same old ecologically destructive methods.

Joseph Kay

I am imagining a scenario of a society a few years into the revolutionary process, after the glut of goods in the warehouses from the capitalist years is gone and we are confronted with the necessity of continuing production.

Joseph Kay

I never said the rise in consumption would be primarily comprised of luxury items --- although I imagine some workers in the third world would love to experience the luxuries that we take for granted. There would also be a rise in consumption in such necessary items as water filtration equipment, fertilizer, farm equipment, medical supplies, building materials (to construct sewers, water filtration plants, hospitals, schools, etc). All of this would also have to be transported to the point of consumption. The bottom line is, even disregarding luxury items, the end of poverty will mean a rise in consumption for those at the bottom that may balance out or exceed the drop in consumption among those at the top and therefore also negate any ecological gains we may have made.

Joseph Kay

Well I'm certainly not predicting immanent revolution. I agree the capitalist "solution" to this problem is something that is "worth thinking about". But surely we can also imagine potential communist solutions. Yes, it's impossible to provide a perfect blueprint of a future society, but I don't see why that means we can't think about the problems a future society might face, and in my view the sooner this conversation begins the better, as the stakes are very high. Capitalism will not solve this problem; any capitalist solution, rather than fixing global warming, will likely only delay the effects.

I actually don't think post

I actually don't think post capitalism this would be a huge problem, as Joseph says initially production would almost certainly drop significantly. As time went on that would probably increase again but at that point there are a lot of things we can organise differently so as to use far less energy than now. We of course can't predict exactly what a communist society would look like but I imagine we would all work less, consume less, share more and have far better public transport, for a start.

I also don't think its true to say that renewable technologies are far from being able to replace all our energy needs. Concentrating solar power alone could supply all our energy with current technology if there was the money/will to do it. And there have been a number of reports showing how to provide all our energy from low carbon sources, I remember one particularly from Greenpeace and David McKays work (which is actually a bit pesimistic I think) for example.

If we manage to get communism before we solve our energy problems I think we'll be fine, so I'd agree with Joseph that's its more useful to consider what happens in the far more likely scenario that we don't.

Just want to say, another

Just want to say, another great blog posts. I think the mini blog explosion libcom's experienced has really ratcheted up the level of discussion.

i have always speculated

i have always speculated about this (less eruditely) with some of my mates, like yourselves unsuprisingly never coming to some certain conclusion. but with all of us landless peasants likely to get it in the neck its hard for thoughts not to take a bit of a survivalist direction.. & a practical direction based on what to do if the half assed semi solution that keeps capitalism staggering on and more and more of us suffering is what manifests. plenty of people have died as result of climate change already and it doesn't seem to have brought us closer to any useful form of social change revolutionary or otherwise.

specifically one thing re tastybrains post is that lots of evidence shows that if circumstances improve for women economically and in terms of access to contraception (and general personal independence would help too) then population levels fall. and in my opinion if anything is to be meaningfully called an anarchist or libertarian communist revolution then these things would occur.

Reproductive Rights and Wrongs : The Global Politics of Population Control by Betsy Hartmann

http://www.southendpress.org/search?query=betsy%20hartmann&by=release_date&search_key=all&page=2

is a good one

although if you want to give a more lively bit of text to someone who thinks that maybe some people will need to die of as part of the world rebalancing itself (as emerged from the mouth of one of my younger friends during a slightly drunken night) then this is better :-

CONQUEST :Sexual Violence and American Indian Genocide by Andrea Smith (one of my favourite books)

http://www.southendpress.org/2005/items/Conquest

Alasdair wrote: I actually

Alasdair

I'm not sure I agree...the production process will have to resume pretty much immediately during and after the revolution. I doubt we will have the luxury of planning a totally new infrastructure before things start up again. I anticipate at least a few years of "intertia" where production, by necessity, is carried out via the same technical means. With so much work to be done in the wake of the revolution I guess I would worry that environmental change would be ignored. That's why I think the conversation about a transition to a communist society that is also in harmony with nature should happen as soon as possible (and the transition should happen as soon as possible if a communist revolution did occur).

Alasdair

Workers with comparatively high incomes in "first world" countries may consume less, but under conditions of global communism surely the majority of people would consume more? Also, if production was conducted in a truly democratic way, people would decide how much they work and consume...some communities might opt for low production and consumption, some for high.

Alasdair

I'll take your word for it. But even so, making the transition to clean energy would require a great deal of labor and would be an intense project.

Alasdair

Why? I think a classless stateless society could still be ecologically harmful. Certainly industrialism was an aspect of classical anarchism, ecology is a relatively recent presence in the anarchist/communist milieu. It could be that we manage to overcome capitalism but get fucked over by the ecological backlash (climate change) because its too late to do anything! (or we could miss our decisive opportunity to halt the progress of climate change by not making it enough of a priority).

Alasdair

I mean, yeah, but assuming we don't we don't have much control over what comes next. Also, whatever "fix"capitalism comes up with will surely be stopgap in nature, imagining a society truly in harmony with nature won't be rendered a waste of time by capitalism's successful resolution of the problem (and its failure would surely render such imagining even more important). Anyway, wanting to defer this discussion to when communism gets here (!) almost seems like an excuse for a paucity of libertarian communist ideas on bringing the economic process into harmony with nature. I realize we can't plan the future society, but I think it's good to have some sort of tentative program or body of thought worked out to deal with climate change and ecological disaster, rather than this sort of "it'll work itself out come the revolution" attitude. That way, when we criticize the capitalists for killing the planet and they say "well what would you do differently" we have something to point to.

tastybrain wrote: Alasdair

tastybrain

You're right that we might overcome capitalism, but do it too late, but that's more of a reason to consider how to engage critically with and to think about what will happen prior to overcoming capitalism. There's no point in us thinking we'll solve the environmental problem after we overthrow capitalism and then realising it's no longer possible when/if we do.

We could also miss our opportunity by not making it a priority, and that might be the worst tragedy. Post revolution I'll certainly argue that it must be a priority, but my point wasn't intended so much that we'll definitely be fine - you're correct in saying that we won't - but that there would be no real forces in the way of our succeeding, perhaps other than time. It will require a lot of effort and restructuring, but the technology all already exists - it just isn't all efficient to deploy under a capitalist economy without some push to overcome the divergence between who can afford the up-front capital costs and who benefits longer term.

tastybrain wrote: the

tastybrain

my last job was in financial services. 30% of the economy in my town is financial and business services. pretty much all that economic activity would just stop. not the most energy-intensive sector for sure, but definite economic collapse. i don't think it's just services either. a huge amount of agricultural production is stuff like flowers or grains to feed cattle. i think a lot of this production would just stop. i wouldn't want to be the one trying to persuade insurgent proles to go back to it! in manufacturing, a huge amount is built to fail (the industry metric is 'mean time between failures' which is kept to the minimum the market will bear, propped up by marketing budgets/deliberately holding back features/cultural expectations of a new X every Y months).

now sure, i still want a laptop and a decent phone. and if i want it, the 6,999,999,999 other people are entitled to it too. that's a lot of production. but i simply can't see, for example, the Foxconn sweatshops carrying on under self-management. We'll have to radically transform the conditions of production if we all want nice shiny iPhones, because without coercion, people simply won't produce them under those conditions. while we're overhauling the whole productive process to humanise it (probably through automation, more socially designed processes etc) we can also factor in energy efficiency.

meanwhile, if the energy sector have been on strike (we had 3 day weeks in the 70s because of this), we could probably simply not fire back up a number of coal power plants and simply make do with less while we build solar farms in the Sahrara, district heating, or whatever. Even at the moment, there's huge efficiencies that could be made which aren't quite profitable enough under current capitalist conditions. e.g. supermarkets use loads of energy on heating, but also produce loads of excess heat from refrigeration (not to mention the hot water requirements of adjacent housing etc). It's technologically feasible to harness the waste heat, but the payback period is something like 5 years when supermarkets want 3. so apart from a handful of flagship projects to bulk out Corporate Social Responsibility reports, it just isn't adopted (even under capitalism, if this was legislated, levelling the playing field, then it could be profitably rolled out).

I'm sure loads of engineers would be itching to get their teeth into projects like these, precisely the kind of technically satisfying applications of knowledge that are continually frustrated by the logic of capital. fuck it, i'd happily help out retrofitting with my new found free time and limited pipe-fitting skills. there's nothing automatic about any of this, sure, but I think huge numbers of people will simply refuse to return to working without radically transforming conditions and processes, and while we're doing that there's a huge opportunity to factor in ecological sustainability imho.

While it is theoretically

While it is theoretically possible that capitalist industries/countries could convert operations to a minimal fossil fuel based system and maintain profitability, there are several reasons to think that this will probably not happen:

1. Time. The lead time needed to research, design, build, and install the solar thermal/solar electric, wind, wave, geo, and biomass replacement for fossil fuels is probably 40 years. By 2050, global warming will either be beyond our control, or we will have attained a less than 400 ppm concentration of CO2 in the atmosphere. I wouldn't count on the latter. Nuclear power plants don't take 40 years to build, but it might take 40 years to complete the conversion to nuclear from fossil fuels.

2. Sacrifice. In order to achieve a stabilization, then reduction of CO2 in the atmosphere in the next 10 years, economic activity will have to slow down dramatically, because industry will have to cease and desist from manufacturing unnecessary consumer goods, and consumers (whose purchases make up more than 70% of the GDP) will have to get along on a good deal less. This will lead to a downward economic spiral -- even with great capital investments in non-fossil energy. I am not suggesting a mild inconvenience here. Reducing CO2 production in the near future (10 to 15 years, max) means a sharp reduction in the quality of life--as citizens of industrialized nations have so far known it.

3. Vested Interests. It seems highly unlikely, extremely unlikely really, that the owners of fossil fuel production, transportation, and use facilities will relinquish what are extremely profitable businesses. It is equally unlikely that consumers in industrial nations (and industrializing nations) will willingly relinquish their chance at a more comfortable life on behalf of a gamble. We might have no choice, at some point, but as long as we have a vote in the market place, economic retrenchment is unlikely to happen.

4. Nature. With respect to the environmental crisis of global warming, capitalists are not evil monsters from hell. Neither are consumers in capitalist countries. Neither are farmers, ranchers, slash and burn agrarians, meat eaters, car drivers, prolific plastic bag wasters, coal miners, and so on. We human beings are behaving normally, for our species. IF we have blundered into our own self-destruction, it is not because we are wicked. It is because we are gifted primates who do not have 20/20 vision into the future.

Yeah I'd agree with that.

Yeah I'd agree with that. Time is the biggest thing, we just don't have it. That said, imho it's still worth working out if capital can in principle adapt, as that will effect what happens in the face of any powerful social movement. The Out of the Woods blog here on libcom is exploring these issues in a more sustained way btw.