Does digital propaganda produced by Western LGBT communities in solidarity with Russian queers expose an exploitative relationship?

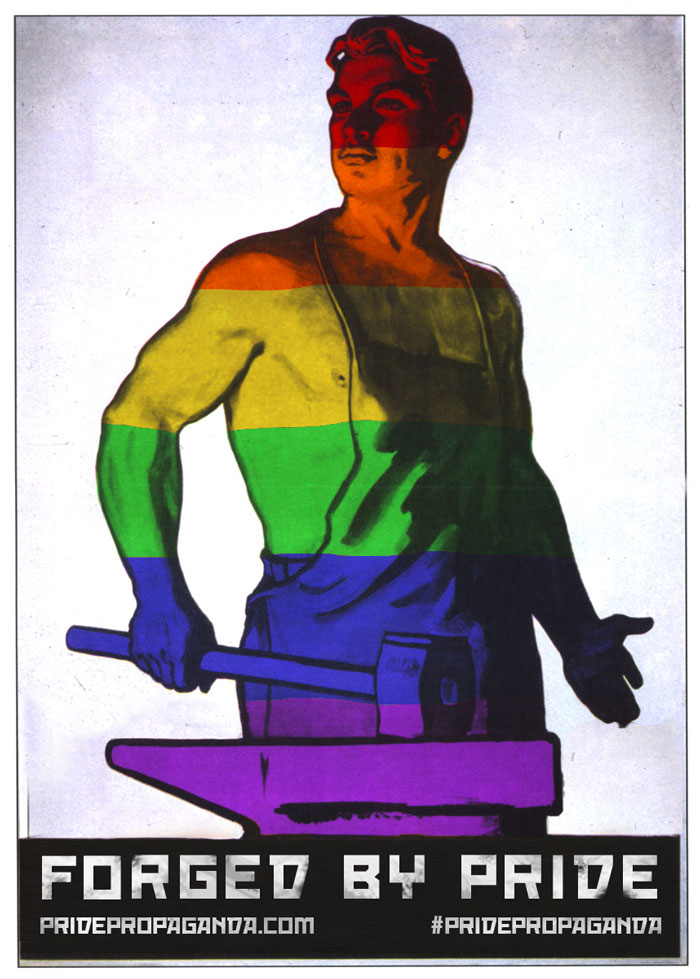

“FORGED BY PRIDE” reads the slogan, embazoned in a mock-Cyrillic typeface across the foot of the poster, produced by Western activists to raise awareness of anti-gay laws in Russia . A URL directs the viewer to a website, pridepropaganda.com, and a readymade hashtag for social network use, #pridepropaganda. The image itself, which forms the main body of the poster, is a stark, early-socialist-realist depiction of a metal worker topless but for his apron, lit up in chiaroscuro by the light of his forge. Across this classic figure of the male manual labourer, a key trope of socialist-realist art, is superimposed the colour of the rainbow flag.

The visual joke is a cheap one; the Russian’s are banning “gay propaganda” aimed at children, a clearly farcical euphemism for material that helps support young LGBT people in the country and sustains a politically-motivated LGBT movement and culture. So why don’t we hit back with our own propaganda, but this time, real propaganda, the sort of stuff we all know is propaganda. Crude falsehoods, utopian nonsenses. You know, Russian stuff. Take some Soviet posters and detourne them as new, ironic gay pride posters. The references of this poster, and the many similar posters released over the past few weeks – a clearly Soviet image, a parodic Cyrillic font, a pro-LGBT slogan and a rainbow flag – are clear and simple; unpacking the image, however, exposes the complex and sometimes exploitative relationship between Russian queers and their Western “allies”, as well as the new dynamics of political image-making online.

What we see in these images is an attempt at detournement, of subverting the image or form in order to expose the power structure behind it and expose it as empty and impotent. But what is the power dynamic at work? Who are the actors behind the image?

The images seem to claim a simple dynamic behind them, a conflict between LGBT people, and the Russian state. You, they declaim, accuse gays of being propagandists; well you asked for it, here it is, steamy hot gay propaganda served up to you on a plate. Look how ridiculous your accusation is. But what’s really operating here is a four-war mexican stand-off between the Russian state, Western LGBT people, Russian LGBT and queers, and the historical memory of the Soviet state. Within that 1000 histories are exposed and obscured, and a number of voices amplified or silenced.

First things first: for whom are these images produced? It’s noticeable that in all the examples I’ve found, the text is in English. It’s fair to assume here that the images are produced for a Western gay audience and their allies. That should directly set alarm bells ringing: as political images, are these posters part of a political struggle, or comments upon a political struggle?

If these images are produced with a non-Russian, anglophone audience in mind, what do they tell us about the audience’s perception of the situation they’re passing comment upon? What do they say about the Western gaze on the Russian subject? The images cast Russia within an historical perspective — a perspective that’s ill-informed, as all these posters are the visual remnants of something that isn’t actually Russia. The Russian Federation is the political entity passing repressive legislation, whilst these posters parody a historically specific entity embodying a quite different ideological position: the Soviet Union. The conflation of Putin’s Russia and the USSR is part of a simplistic exoticisation of the political situation, and of Russian people and their cultures.

This conflation reinserts the current struggle of Russian queers within the context of an historical conflict — the Cold War — that is profoundly linked with ideas of a threat to Western European “civilization” — a racialised concept — from a totalitarian threat from the East. These threats, which form part of the “Russian imaginary” in Europe are a combination of a totalitarian threat to “personal liberties” and a sexual threat. Perhaps it’s this threat to personal liberty, embodied in a conflated Russian/Soviet identity, that these posters seek to defend against by undermining in tongue-in-cheek fashion.

In doing so, however, they ignore the actual historical facts of attitudes to homosexuality in the USSR, Europe and the US in order to achieve, at best, a cheap rhetorical strike, and, at worst, a counter-productive racist backlash against ordinary Russian people. In fact, by better understanding Russian attitudes to homosexuality we can shed light on exactly why Putin has pushed through anti-gay laws, and perhaps conduct more intelligent and sympathetic solidarity campaigns to support queer comrades in Russia.

As a quick rejoinder to the idea that Russians are somehow naturally backwards in their attitudes to gay rights, it’s worth pointing out that the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic first decriminalised same-sex activity in 1917, a full 50 years before England and Wales. Of course, this isn’t to say that life for gays in the early USSR was easy for gay people, and prohibitions stayed in place in many Soviet republics. Prohibitions on male homosexual activity were reintroduced as part of criminal code in 1933. But it certainly complicates the ironic tone of the parody posters to note that, when some of them were produced, there were no legal prohibitions in place in Russia, and Moscow was engaging with the sexual research conducted by Magnus Hirschfeld in Berlin. Meanwhile, for much of the Cold War, homosexuality was also intrinsically and intentionally tied to the Red Menace in the West in order to discredit both — from the Lavender scare and Bayard Rustin to the Cambridge Five and ongoing concerns about the susceptibility of homosexual intelligence agents to blackmail.

More importantly, by removing these images from their ahistorical role of exoticising Russian culture, we can perhaps understand why Putin is enacting repressive anti-gay policies now, when he had little active focus on them earlier in his rule. Indeed, Putin’s reasons bear comparison to the reasons Stalin reintroduced prohibitions in the 1930s. Faced with a need to bolster the support from traditional organisations and communities, both Putin and Stalin mobilised the spectre of rootless, liberal, weak cosmopolitanism being imported from Western Europe, threatening to undermine the social cohesion of Russian society and fatally weakening the Russian state. In order to shore up their support they appealed to both nationalist narratives and religious sentiments, and both used homosexuality as a tool of this retrenchment.

Homosexuality, and homosexuals, have been recast as a fire in need of extinguishing. Knowing this should perhaps have an effect on the nature of solidarity campaigns with Russian queers coming from Western allies. Even well-meaning gestures can be seized upon as proof by Putin of the seditious nature of homosexuality. This isn’t to say we should do nothing to support our queer comrades, simply that the starting point of any solidarity work must be to listen to the explicit requests and material demands of those with whom we are claiming to act in solidarity. The attempts at pursuing a Russian vodka boycott, for example, were explicitly condemned by Russian queers as dangerously counter-productive, yet those calls continue to resonate in Western LGBT circles.

Why do these continue, despite the requests of those they’re intended to help? And what is the relationship of that dismissive attitude to these images? At this point it’s important to return to the posters. Perhaps we’ve made a category error in describing them as posters at all. Whilst the originals were designed by hand, and then lithographed for mass-distribution on walls across the USSR, these images have been produced in photoshopped, and not printed in runs, if at all. In their file size, emblazoned with URLs and hashtags, these images are designed to be digitally distributed via social medias, through networks. They’re pre-engineered for virality, to spread through English-speaking social networks as fast and widely as possible. Each share or retweet represents a strand in the construction of a shared political subjectivity, which is, after all, the very purpose of propaganda. But that shared subjectivity is within Western LGBT communities. This is the social group these images intend to bond together — not Russian queers, the people actually affected by Putin’s laws. And that Western group is fast building its subjectivity around images that exoticise Russia people, and place them within a Cold War culture of distrust and conflict.

It speaks volumes that the art of these original propagandists serves so well in drawing the attention of the contemporary Western LGBT eye. Decades after they were first produced, Socialist Realist images retain their aesthetic and ideological power, even when repurposed. Triumphalist and based around the political subject as potent, noble, brave: they still speak to our fictive self-image as a community based around cohesive bonds of solidarity and shared struggle. These images aren’t fully subverted; they remain only half ironic. To me, the campaign of “solidarity” with Russian LGBT people conducted in Europe and the US seems to be far more about desperately trying to maintain the crumbling delusion of a united LGBT community with a shared political struggle, than it does about addressing the urgent needs and requests of Russian queers fighting state and political violence. At our political nadir since the AIDS crisis, the LGBT orthodoxy search for vicarious struggle, even if it involves imposing an ahistorical, uncritical liberation narrative onto people facing terrible oppression from state power abroad. Perhaps distraction is welcome from the failings and divisions within LGBT communities in the West, with class and racial divisions and an increasingly dominant, privileged “G” caucus celebrating limited legal civil rights whilst working-class queers and trans* people still face discrimination and punishment under austerity and discriminatory criminal and employment codes. The whole of Europe and the US remains a deeply hostile environment for most LGBT people, even if we achieve slightly more visibility, and a few more bourgeois rights.

If the aim of propaganda is building a cohesive and informed political subjectivity, then I, for one, am all for gay propaganda, and the more of it aimed at children the better. Queer kids spend their whole life fending off the micro- and macro-aggressions of the heterosexual regime, and a bit of solidarity and respect for their social and sexual autonomy is a welcome change from the derision and assaults they face. But images, as Paris-Clavel said, become political as a result of their insertion into struggle. They are produced from the material needs of the struggle, and travel and die alongside it, as provocations, contestations and incitements. Propaganda produced outside a struggle is dessicated, like dust in the wind. When it serves to valorise racist self-indulgences, when it stifles those it claims to speak for, it chokes the throat and it blinds the eyes of those in struggle.

Comments

I thought this was well

I thought this was well smart. Looking forward to more blogs from you.

This is pretty

This is pretty good.

I'm certainly not an expert but my understanding of the reintroduction of article 121 was that it was justified by connecting it with Fascism not liberalism.

Reddebrek wrote: This is

Reddebrek

Yup totally different ideological projects. But with similar economic foundations.

dp

dp

Yeah, great blog and looking

Yeah, great blog and looking forward to more!

(A small sub editing note, there is an asterisk after the word trans, is there a missing footnote? And also I replaced all the links to external images by attaching the image files directly to this article to ensure that they remain here in the future. If you could attach image files directly in future that would be great!)

I see that trans* asterisk

I see that trans* asterisk used a lot. I don't understand fully exactly what it means but I think it denotes that trans is not a binary thing (e.g. it's more complicated than all trans people being either a trans-man or trans-woman). I should probably leave the explanation to someone more clued-up, just wanted to point out it was probably used on purpose.

Yeah, when Facebook

Yeah, when Facebook introduced all those new gender options, I know that trans asterisk was one of them. Although like Wotsit, I'm not actually sure why/how it's used.

My understanding is that the

My understanding is that the * in trans* is like when you put an asterix in a search function. So 'trans*' stands for 'transgender', 'transsexual' 'trans man/woman' & then also for, for example, 'genderqueer' & other non-binary gender identities.

In short, it's intended as a more inclusive term for a spectrum of experiences/identities.

Now I'm going to go read the article!

The Soviet Union did not

The Soviet Union did not legalise homosexuality in 1917 - this is a myth.

They abolished the entire old Tsarist legal code.

So technically murder was also 'legal' for several years.

Apart from that, great piece.