A short history of the mutiny at Taranto in Italy by West Indian soldiers in the British army at the end of World War I, which had a significant impact subsequently on anti-colonial struggles in the Caribbean.

Introduction

With the outbreak of the First World War in 1914, thousands of Caribbeans volunteered to join the British army. They were encouraged to do so by activists like Marcus Garvey, on the basis that if they showed their loyalty to the King they would show they have the right to be treated as equals.

Initially, the Secretary Of State for War Lord Kitchener believed that Black British soldiers should not be allowed to join the forces, but King George V's intervention - combined with the need for men - made it possible.

Thousands of West Indians volunteered. Their initial journey to England was perilous, with hundreds of soldiers suffering from severe frostbite when their ships were diverted via Halifax in Canada. Very many had to return home no longer fit to serve as soldiers, with no compensation or benefits.

In 1915, the British West Indies Regiment was formed by grouping together the Caribbean volunteers. This should not be confused with the West India Regiment, founded in 1795, which was normally stationed in the British colonies in the Caribbean themselves.

BWIR Troops stacking shells. © IWM E(AUS) 2078

The commanding officers were all white, and no black officer could occupy a position higher than sergeant.

Arriving in the war zone, they found that the fighting was to be done by white soldiers, and that West Indians were to be assigned the dirty and dangerous work of loading ammunition, laying telephone wires and digging trenches. Most of them went to war without guns.

Conditions were appalling. George Blackman, a Barbadian member of the fourth division, when recounting conditions to a journalist rolled up his sleeve to show his armpit: "it was cold. And everywhere there were white lice. We had to shave the hair there because the lice grow there. All our socks were full of white lice."

This poem by one of the troops, The Black Soldier's Lament, showed the bitterness with which this was experienced:

Stripped to the waist and sweated chest

Midday's reprieve brings much-needed restFrom trenches deep toward the sky.

Non-fighting troops and yet we die.

During the war, 15,600 men in the regiment's 12 battalions served with the Allied forces, with two thirds of the volunteers coming from Jamaica and the rest from Trinidad and Tobago, Barbados, the Bahamas, British Honduras (now Belize), Grenada, British Guiana (now Guyana), the Leeward Islands, St Lucia and St Vincent.

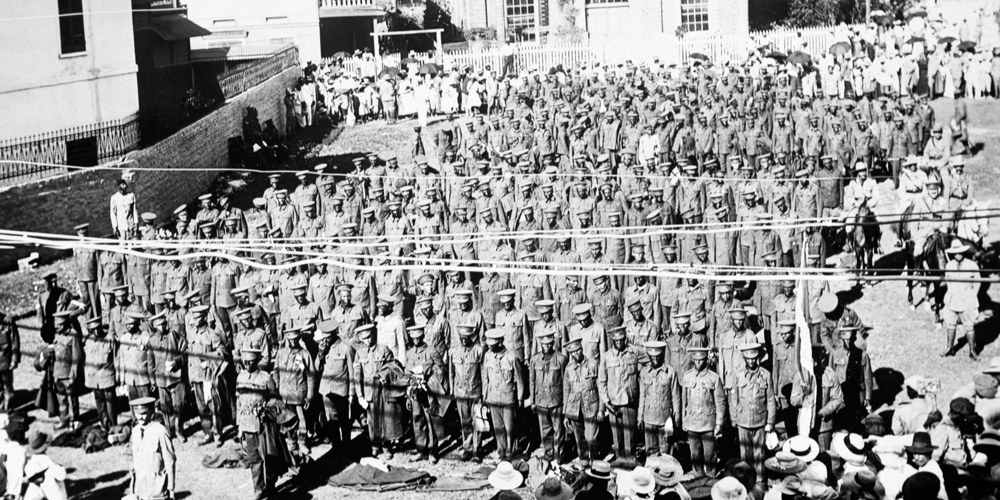

BWIR troops being inspected in Jamaica. © IWM Q 52423

It was active in a number of areas including playing a vital role in active combat against the Turkish army in Palestine, Jordan and Mesopotamia (modern day Iraq) and in France, Italy and Egypt where the men served mainly in auxiliary roles. There is evidence that there were also armed skirmishes with German troops in France.

One Trinidadian soldier in Egypt wrote to a friend saying that: "We are treated neither as Christians nor as British citizens, but as West Indian ‘n***ers" without anybody to be interested in nor look after us”.

Mutiny

After Armistice Day, on 11 November 1918, the eight BWIR battalions in France and Italy were concentrated at Taranto in Italy to prepare for demobilisation1 . They were subsequently joined by the three battalions from Egypt and the men from Mesopotamia. As a result of severe labour shortages at Taranto, the West Indians had to carry out arduous physical tasks. They had to load and unload ships, do labour fatigues2 and perform demeaning tasks like building and cleaning toilets for white soldiers, which all caused much resentment. As did the discovery that white soldiers were being given a pay rise while black soldiers were not.

By 6 December 1918 they had had enough: the men of the 9th Battalion revolted and attacked their Black officers. On the same day, 180 sergeants forwarded a petition to the Secretary of State complaining about the pay issue, the failure to increase their separation allowance, and the fact that they had been discriminated against in the area of promotions.

During the mutiny, which lasted about four days, a Black NCO shot and killed one of the mutineers in self-defence and there was also a bombing. Disaffection spread quickly among the other soldiers and on 9 December the 'increasingly truculent' 10th Battalion refused to work. A senior commander, Lieutenant Colonel Willis, who had given the orders to BWIR men to clean the latrines of the Italian Labour Corps, was also subsequently assaulted.

In response to calls for help from the commanders at Taranto, a machine-gun company and a battalion of the Worcestershire Regiment were despatched to restore order. Perceived ringleaders were rounded up. The 9th BWIR was disbanded and the men distributed to the other battalions which were all subsequently disarmed.

Approximately 60 soldiers were later tried for mutiny and those convicted received sentences ranging from three to five years, but one man got 20 years, while another was executed by firing squad. The BWIR itself was disbanded in 1921.

Aftermath

Although the mutiny was crushed, the bitterness persisted and on 17 December 1918 about 60 NCOs held a meeting to discuss the question of Black rights, self-determination and closer union in the West Indies. An organisation called the Caribbean League was formed at the gathering to further these objectives. At another meeting on 20 December, under the chairmanship of one Sergeant Baxter, who had just been superseded by a white NCO, a sergeant of the 3rd BWIR argued that "the Black man should have freedom and govern himself in the West Indies and that if necessary, force and bloodshed should be used to attain that object". His sentiments were loudly applauded by the majority of those present. The soldiers decided to hold a general strike for higher wages on their return to the West Indies.

Back in the West Indies, between 1916 and 1919 a number of colonies including St Lucia, Grenada, Barbados, Antigua, Trinidad, Jamaica and British Guiana were experiencing a wave of often violent strikes.

It was into this turmoil that the disgruntled BWIR soldiers began arriving back. There were no welcome parades or celebrations of their contribution to the war effort. Instead, fearing unrest the British government moved three cruisers with machine guns into docks at Barbados, Jamaica and Trinidad. Thousands of former soldiers were displaced to nearby countries like Cuba and Venezuela.

But despite this, many more joined the wave of worker protests resulting from a severe economic crisis produced by the war. Disenchanted soldiers and angry workers demonstrated, went on strike and rioted in a number of territories including Jamaica, Grenada and especially in British Honduras.

A secret colonial memo from 1919, uncovered by researchers for a Channel 4 programme on the Taranto mutiny, showed that the British government realised that everything had changed, too: "Nothing we can do will alter the fact that the Black man has begun to think and feel himself as good as the white."

Sources

- West Indian soldiers in the First World War - Arthur Torrington - retrieved on 07.08.13

- Encyclopedia of World War I By Spencer Tucker, Priscilla Mary Roberts (p.508)

- Caribbean participants in the First World War - retrieved on 06.08.13

- We were there - West Indians in the British armed forces - retrieved on 06.08.13

- Black history: Civil rights and equality - Dan Lyndon

- The West India Regiment - retrieved on 07.08.13

- "There were no parades for us" - retrieved on 07.08.13

- The British West Indies Regiment - retrieved on 07.12.15

- Trinidad and Tobago's first general strike - retrieved on 19.06.17

Comments

Great article! Not very…

Great article! Not very relevant but I just noticed that the captions for a couple of the photos are for different images.

"BWIR troops being inspected in Jamaica" should be for the photo "BWIR Troops stacking shells." and vis versa.

Great spot, thanks

Great spot, thanks