An introduction to the Lucasville Uprising on April 1993, compiling the "Background" section of the Lucasville Uprising site and "Re-Examining Lucasville" by Staughton Lynd.

BACKGROUND

This background is based on the information contained in Staughton Lynd’s book, Lucasville: The Untold Story of a Prison Uprising, various other sources, and correspondence with prisoners involved.

Here is a detailed factual timeline of events based on testimony and evidence presented in court. Staughton is also putting together a series of essays leading up to the 20th anniversary conference of the Uprising.

Where and when was the Lucasville Uprising?

The uprising occurred April 11-22, 1993, at Southern Ohio Correctional Facility (SOCF). SOCF is located outside the village of Lucasville in Scioto county. Like most prisons, SOCF’s placement in this rural setting exaggerates cultural and racial divides between the prisoner population (largely urban people of color) and the rural white guards.

What were conditions at SOCF at the time of the uprising?

What were conditions at SOCF at the time of the uprising?

In 1993, SOCF was overcrowded, violent, repressive, hard to transfer out of, and and dangerous to live in. Fights were incredibly common. Guards smuggling weapons and contraband was a known practice. Prisoners sent to segregation or “the hole” where often beaten and sometimes murdered by guards, with no consequences.

Prisoners attempted to defend themselves through legal and non-violent channels exhaustively. Attempts to renounce US citizenship, to form a prison labor union, and to send Amnesty International a petition listing violations of the United Nations Minimum Standards for the Treatment of Prisoners were repressed by the administration and ignored by the courts. The Amnesty International petition, for example, was confiscated as contraband by SOCF and the authors were charged with “unauthorized group activity.”

A major turning point in the history of Lucasville came in 1990, when Beverly Taylor, a female tutor was murdered by a mentally unstable prisoner whom the prison administration had appointed as her aide. This incident incensed the citizens of southern Ohio, who demanded changes at Lucasville.

What caused the uprising?

People who lived near SOCF demanded changes that empowered the administration, punished prisoners and only made the situation worse. Following the teacher’s death, a new warden named Arthur Tate came in and instituted “Operation Shakedown.” This new program started with searching all the cells, destroying prisoner’s personal property in front of them and went on to impose a number of arbitrary and often inhumane rules, encouraging snitching, and increasing stress, resentment, and insecurity for the prisoner population.

Tate also requested additional funding and an expansion of the super-max security wing. Prison spending was a hot issue, and given that SOCF never filled the super-max cells it had, politicians couldn’t sell the public on this expansion plan. Meanwhile, Tate increased repressive policies and became more and more unreasonable. Looking back on Tate’s actions after the uprising, some prisoners believe that he was trying to provoke violence in order to justify his expansion plans.

Non-violent resistance to SOCF policies continued and increased during “Operation Shakedown.” Prisoners desperately sought support from the outside world. Almost immediately after Tate’s arrival, a group of prisoners took a correctional officer hostage and demanded to broadcast a statement on a local radio station. After hearing the broadcast, the hostage was freed unharmed. This incident shows the desperate lengths prisoners had to go to get any recognition of their plight in the outside world. This incident successfully caught the attention of federal courts, bringing some help and oversight into SOCF.

Only this dangerous and aggressive action yielded results. Tate became always more unreasonably stubborn and arbitrary, escalating tensions over minor issues, until the prisoners broke into a full-on violent revolt.

How did the uprising begin?

Warden Tate mandated that all prisoners be subjected to a TB test that involved injecting alcohol (phenol) under their skin. A large group of Sunni Muslims objected to this test because it violated a tenet of their faith. Tate refused to allow these prisoners an alternative to the injection test, even though saliva testing is at least as affordable, reliable and easy to administer. In a meeting with Muslim leaders six days prior to the uprising, Tate assured them that if they refused, they would be forced to take the injections in their cell blocks in front of the other prisoners, the approach that was most likely to provoke violent resistance.

On Sunday, April 11th, the day before TB testing was scheduled to take place, a group of prisoners took action. Their intention was to take control of and barricade themselves in a single living area or “pod” and demand someone from the Central Office in Columbus review the testing procedure. This did not work out as planned. It’s unclear whether guards fought back, rather than surrendering the keys, or if the prisoners let years of abuse get the best of them, probably some of both, but the action quickly escalated and within an hour the prisoners had taken over the whole cell block, including 11 guards. Hundreds of prisoners, many of whom were on their way in from outdoor rec time, were now either in the occupied cell block or on the yard outside of it.

Who was involved in the uprising?

Early on, amidst the chaos and fighting, there were cries of “Lucasville is ours! This is not racial, I repeat, not racial. It’s us against the administration! We’re tired of these people fucking us over. Is everybody with us? Let’s hear ya.” The prisoners roared their approval and the uprising expanded beyond this specific group of prisoners upset with TB testing methods. Members of all the prison factions, including the Gangster Disciples and the Aryan Brotherhood stood in solidarity as convicts against their common oppressors: the prison administration and the state of Ohio.

That night, three of the eleven hostage guards were released in need of medical attention. The bodies of five suspected snitches, and three injured prisoners were also placed on the yard. By 3:21 am the next morning, prisoners who remained on the yard rather than in the cell block surrendered to the authorities, who rounded them up, stripped them of all clothes and possessions and packed them naked, ten to a cell in another block.

Over 400 prisoners remained in the occupied cell block. They spent the next 11 days working together to negotiate a peaceful conclusion to the uprising.

How did prison racial factions impact the uprising?

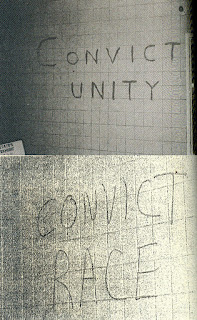

Graffiti at SOCF found after the Uprising

Graffiti at SOCF found after the Uprising

Racialized gangs are a norm in prison, prison administrators often manipulate these gangs to turn convicts against each other. Prison administrators surely expected, and perhaps Warden Tate intended to provoke a race-war and a blood bath. The media prematurely reported as much, telling their viewers entirely false stories of dozens of bodies piling up inside the occupied cell block.

In actuality, the prisoners worked together against their common foes. Factions split up into different parts of the occupied cell block, but coordinated activities through a group of representatives who negotiated demands to bring an end to the uprising. Prisoners recognized the racial tensions in the situation, but had enough experience dealing with each other across racial boundaries to quickly adopt a few basic policies to prevent disaster and establish convict solidarity. Many of these policies were practical decisions, based on an understanding of the racism that exists both inside and outside of the prison. Each faction disciplined their own, white hostages who were known racists were held by the Aryan Brotherhood, members of each faction got together to work out demands and conduct negotiations. They chose a member of the Aryan Brotherhood to act as the initial spokesperson for the occupation, knowing that the public and the administration was more likely to hear what he said. At the end of the eleven days, a group of three representing each of the gangs involved, negotiated the details of the surrender.

How violent was the uprising?

The convicts created a structure to keep relative stability and peace. They collected all the food in a central location, to be distributed equitably later. They created a rudimentary infirmary, “no weapons” zones, guard posts and a group of representatives from each faction to negotiate with each other and the state.

There were relatively few severe injuries or deaths. Nine perceived informants were killed, and one hostage guard, over the course of eleven days. Compared with other prison uprisings, Lucasville lasted longer with a lower per-day death toll than most and is the only prison uprising of its size to end in peaceful negotiated surrender. For a counter-example, America’s most famous prison uprising, 1971 in Attica, 3 prisoners and 1 guard were killed over the course of 4 days. Attica ended when soldiers stormed the compound, killing 29 prisoners and 10 guards.

How did the state conduct themselves during the uprising?

The state refused to negotiate or recognize the prisoners’ demands from the start. When prisoners rigged up a loudspeaker system in order to communicate with reporters outside, prison officials first drowned it out with a helicopter, then shut off the water and electricity. Prisoners resorted to writing messages on sheets hung out the windows and listening to news via battery powered radios in hopes that their messages were getting through. Meanwhile, the state was stalling and amassing troops for an assault.

On the 4th day of the uprising, a spokesperson from SOCF took questions from the media and when asked about messages on bedsheets threatening to kill guards if demands aren’t met, she disregarded the threat as “part of the language of negotiations” and described prisoners demands as “self-serving and petty.” The state didn’t take the negotiations seriously until the next day, when prisoners delivered the dead body of one of the hostage guards to the yard.

Who killed Officer Vallandingham, and why?

The answer to that question is legally disputed, but a good look at the evidence, testimony and even post-trial statements of prosecutors and other officials suggest that one of the negotiators, Anthony Lavelle, decided to carry out the threat without agreement of the other prisoner negotiators. He assembled a small group of prisoners, who wore masks and killed Officer Vallandingham. This killing appears to have prevented the state from staging an armed assault on the occupied cell block and to finally begin negotiating in earnest with the prisoners.

How did the uprising end?

The uprising ended with prison officials agreeing to a 21-point negotiated surrender with the prisoners. The first point prisoners demanded was: “There must not be any impositions, reprisals, repercussions, against any prisoner as a result of this that the administration refers to as a riot.” The second point was: “There must not be any singling out or selection of any prisoner or group of prisoners as supposed leaders in this alleged riot.” Much of this language remained in the final agreement. Many of the other demands were that the prison be run according to its own rules, regulations and standards.

What happened after the uprising?

The state violated this agreement. Some prisoners were singled out as leaders and subjected to reprisals, beatings, manipulation and twisted mockeries of trials. The state decided that the crime scene was “too contaminated” to pursue physical evidence and instead chose to base their investigation primarily on witness testimony. They destroyed much physical evidence and went after anyone who refused to be witnesses and snitch out other prisoners. True to form in the American criminal justice system, who actually did what is less important than who is willing to cooperate and bargain with the state. Those who refused to testify against others were branded “the worst of the worst” and given harsh penalties, including death. Those who were willing to testify were sent to Oakwood Correctional Facility, where they got special treatment, were threatened, coerced, and received coaching on exactly what the state wanted them to tell a jury. Oakwood was later dubbed the “snitch academy” by other prisoners.

Ironically, Anthony Lavelle, the man who most likely killed Officer Vallandingham was the state’s star witness against the other Lucasville negotiators. He is currently serving 7-25 years, while others charged with the officer’s murder appeal their cases on death row.

The state of Ohio and the Ohio State Highway Patrol did everything they could to prevent a fair trial at every stage in the process. They obstructed the accused’s access to counsel, evidence, resources, fair court rooms and impartial juries.

Cases are still being appealed and argued. Some of the prisoners have made recent gains, acquiring access to evidence that had been previously denied. Others, continue to struggle against magistrates who refuse to acknowledge glaring faults in the trials and Judges refuse to hear or grant appeals.

Where are the Lucasville Uprising prisoners at now?

Following the uprising, the state of Ohio built a supermax facility outside Youngstown called Ohio State Penitentiary (OSP). Many of the 40-some prisoners sentenced after the uprising were transferred to OSP when it opened in May 1998. OSP is a 504-inmate capacity super max prison. As of Mid-January 2012, it houses 90-100 level 5 supermax prisoners, around 170 level 4 prisoners, and 6 death row level 5 prisoners (4 of whom were involved in the Lucasville uprising) all are single-celled as described above. There are also around 230 lower level “cadre” prisoners (housed in a separate building) who are there to do forced labor maintaining the facility.

Ohio State Penitentiary

Ohio State Penitentiary

Many super-max prisoners at OSP are housed in solitary confinement 23 hours a day, in 89.7 squre foot cells (a little more than 7 x 11 feet). They get very little sunlight or human contact. Some of the Lucasville Uprising prisoners have been held in these or similar conditions at other facilities since 1993.

OSP cost $65 million to build and over $32 million a year to run, that’s almost $150 per prisoner, per day. Much of this money goes to private companies contracted to build, maintain, and provide unfairly expensive communication, commissary and other services to the prison. Clearly Arthur Tate’s belligerence and provocation of Lucasville prisoners got the funding and prison expansion he was looking for, and then some.

What can we do to change their fates?

Our first goal is to increase awareness of the uprising and to tell the stories of the many prisoners unjustly suffering punishments for their attempt to resist unimaginable oppression. You can help ease that suffering by writing to the prisoners and by donating to their support effort. You can fight for justice by supporting them in court, opposing the death penalty in Ohio, writing letters or calling the Warden at OSP or the Ohio Department of Rehabilitation and Corrections (ODRC). You can increase awareness by hosting a screening of The Shadow of Lucasville, organizing other events, rallies, or protests.

Many of these prisoners are ready to fight for their rights. At the start of 2011, the death sentenced Lucasville Uprising prisoners held at OSP had one hour of solitary rec time a day, they were separated from their visitors by bulletproof glass, they had very limited access to telephones and legal resources, and no chance of having their security level dropped. They had endured these conditions, including no human contact other than guards for 18 years. Now, because of a series of hunger strikes and organizing efforts, they are allowed to rec in pairs, have access to legal databases, one hour of phone access per day, and full contact visits with their loved ones. These changes allow them to demonstrate that they are not a danger to others and thus should help them eventually reduce their security level.

On the 20th anniversary of the Uprising, organizers held a 3 day conference. This conference produced a resolution demanding amnesty for all of the Lucasville Uprising prisoners. Let them free.

We are not claiming that all of these prisoners are innocent (though some surely are). We are claiming that none of them received anything like a fair trial. We’re also claiming that the state and the ODRC are primarily responsible for the conditions that caused the uprising, and for the violence that took place during it. Holding ODRC accountable starts with amnesty for these prisoners.

We also recognize that heinous conditions continue at SOCF, OSP and many other prisons in Ohio. We know that mass incarceration traumatizes and breaks up our communities, is used predominantly against poor and working people, is racist, dehumanizing and ultimately serves no legitimate purpose. Prison exists to make money for corporations, to protect the vast inequality that has taken hold of our country and to keep minority populations and communities down. We defend the Lucasville Uprising prisoners in the name of any prisoner who also longs for freedom, who longs to break out of their chains and to resist the torments visited upon them by the prison system.

ABOLISH PRISON!

FREE ALL PRISONERS!

RE-EXAMINING LUCASVILLE

by Staughton Lynd

Staughton Lynd is the author of Lucasville: the Untold Story of a Prison Uprising and Layers of Injustice. He and his wife Alice have been steadfast organizers with the Lucasville Uprising prisoners since 1996. The Lynds have been labor lawyers and civil rights activists since the 1960s. Staughton made this statement at the Re-Examining Lucasville Conference.

Our focus this morning has been a detailed discussion of what happened before and during the eleven days and in the trials that followed. My comments are intended to build a bridge between that analysis and the broader perspectives that will be offered this afternoon. I will divide my remarks in four parts. First, I shall recall the three biggest prison rebellions in recent United States history. I will suggest that while we are just beginning to build a movement outside the walls of both prisons and courtrooms, there are particular aspects of the Lucasville events that help to explain why that has been so hard.

Second, I will make the case that, despite appearances, Ohio’s prison administration was at least as responsible as were the prisoners for the ten deaths during the occupation of L block.

Third, I shall describe the manipulation by means of which the State of Ohio induced a leader of the uprising to become an informer and to attribute responsibility for the murder of hostage Officer Robert Vallandingham to others. I shall add that to this day the State says it does not know who the hands-on killers were.

Finally, and very briefly, because I recognize this will be the agenda for tomorrow morning, I will ask: What is to be done?

Three Prison Uprisings

There have been three major prison uprisings in the United States during the past half century.

The first and best-known rebellion was at Attica in western New York State in September 1971. Prisoners occupied a recreation yard. After three days, agents of the state assaulted the area, guns blazing. The prisoners had killed three prisoners and a guard. The state’s assault resulted in the deaths of 29 more prisoners and an additional 10 guards whom the prisoners were holding as hostages.

Initially the State of New York, including Governor Nelson Rockefeller, claimed that the hostage officers who died in the yard had their throats cut by the prisoners in rebellion. A courageous medical examiner said, No, the officers all died of bullet wounds. And only one side in the conflict, or massacre, had guns.

Because the brazen cover story of the authorities was so soon and so dramatically refuted, the prosecution of prisoners at Attica never got far off the ground. On December 31, 1976, a little more than five years after the events at the prison, New York governor Carey declared by executive order an amnesty for all participants in the insurrection. He stated in part:

Attica has been a tragedy of immeasurable proportions, unalterably affecting countless lives. Too many families have grieved, too many have suffered deprivations, too many have lived their lives in uncertainty waiting for the long nightmare to end. For over five years and with hundreds of thousands of dollars and countless man-hours we have followed the path of investigation and accusation. . . . To continue in this course, I believe, would merely prolong the agony with no better hope of a just and abiding conclusion.

The governor concluded by saying that his actions should not be understood to imply “a lack of culpability for the conduct at issue.” Rather, Governor Carey stated, “these actions are in recognition that there does exist a larger wrong which transcends the wrongful acts of individuals.”

In 1980 a second major uprising occurred at the state prison in Santa Fe, New Mexico. Again there were numerous deaths, but all 33 homicides resulted from prisoners killing other prisoners. No officers were murdered. No prisoner was sentenced to death.

Finally we come to the Southern Ohio Correctional Facility in Lucasville in 1993. In trying to understand the tangle of events we call “Lucasville” one confronts: a prisoner body of more than 1800, a majority of them black men from Ohio’s inner cities, guarded by correctional officers largely recruited from the entirely, or almost entirely, white community in Scioto County; a prison administration determined to suppress dissent after the murder of an educator in 1990; an eleven-day occupation by more than four hundred men of a major part of the Lucasville prison; ten homicides, all committed by prisoners, including the murder of hostage officer Robert Vallandingham; dialogue between the parties ending in a peaceful surrender; and about fifty prosecutions, resulting in five capital convictions and numerous other sentences, some of them likely to last for the remainder of a prisoner’s life.

The task for defense lawyers, and for a community campaign demanding reconsideration, is more difficult than at Attica or Santa Fe. At Attica, 10 of the 11 officers who died were killed by agents of the State. At Santa Fe, only prisoners were killed. Lucasville presents a distinct challenge: the killing of a single hostage correctional officer murdered by prisoners in rebellion.

Who Is To Blame?

In a summary booklet Alice and I have produced, entitled Layers of Injustice, we argue that the Lucasville prisoners in L block, considered collectively, and the State of Ohio share responsibility for the tragedy of April 1993. Both sides contributed to what happened. Events spun out of control. Neither side intended what occurred.

The collective responsibility of prisoners in L-block seems self-evident. Ten men were killed. The victims were unarmed and helpless. In contrast to what happened at Attica, all ten victims were killed by prisoners.

However, Muslim prisoner Reginald Williams, a witness for the State in the Lucasville trials, testified that the hope of the group that planned the 1993 occupation was to carry out a brief, essentially peaceful, attention-getting action “to get someone from the central office to come down and address our concerns” (State v. Were I at 1645), “to barricade ourselves in L-6 until we can get someone from Columbus to discuss” alternative means of doing the TB tests (State v. Sanders at 2129.) Siddique Abdullah Hasan, supposed by the State to have planned and led the action, said the same thing to the Associated Press within the past two weeks.

Since the prisoners, whatever their initial intentions, nonetheless carried out the homicides, the responsibility of the State is less obvious. Here are some of the main reasons I believe that the State of Ohio shares responsibility for what happened at Lucasville in 1993.

1. In 1989, Warden Terry Morris asked the legislative oversight committee of the Ohio General Assembly to prepare a survey of conditions at the Southern Ohio Correctional Facility in Lucasville. The Correctional Institution Inspection Committee received letters from 427 prisoners and interviewed more than 100. Such was the state of disarray in 1989 that, four years before the 1993 uprising, the CIIC reported that prisoners “relayed fears and predictions of a major disturbance unlike any ever seen in Ohio prison history.”

2. After the murder of educator Beverly Jo Taylor in 1990, a new warden was appointed. Warden Arthur Tate instituted what he called “Operation Shakedown.” A striking example of the pervasive repression reported by prisoners is that telephone communication between prisoners and the outside world was limited to one, five minute, outgoing telephone call per year.

3. The single feature of life at Lucasville that the CIIC found most troublesome was the prison administration’s use of prisoner informants, or “snitches.” Warden Tate, “King Arthur” as the prisoners called him, expanded the use of snitches. In 1991 the warden addressed a letter to all prisoners and visitors in which he provided a special mailing address to which alleged violations of “laws and rules of this institution” could be reported. Six alleged snitches, a majority of the persons murdered during the rebellion, were killed in the first hours of the disturbance.

4. The immediate cause or trigger of the rebellion was Warden Tate’s insistence on testing for TB by injecting a substance containing phenol, which a substantial number of Muslim prisoners believed to be prohibited by their religion. Alternative means of testing for TB by use of X rays or a sputum test were available and had been used at Mansfield Correctional Institution. In its post-surrender report, the correctional officers’ labor union stated that Warden Tate was “unnecessarily confrontational” in his response to the Muslim prisoners’ concern about TB testing using phenol.

5. Before Warden Tate departed for the Easter weekend on Good Friday, three of his administrators advised against his plan to lock the prison down and forcibly inject prisoners who refused TB shots. The warden did not adequately alert the reduced staff who would be on duty as to the volatile state of affairs. Slow response to the initial occupation of L block let pass an early opportunity to end the rebellion without loss of life. It was two hours after the insurgency began before Warden Tate was notified. The safewells at the end of each pod in L block, to which correctional officers retreated as they had been instructed, turned out to have been constructed without the prescribed steel stanchions and were easily penetrated.

6. Sergeant Howard Hudson, who was in the administration control booth during the eleven days and was offered by prosecutors as a so-called “summary witness,” conceded in his trial testimony that the State of Ohio deliberately stalled when prisoners tried to end the standoff by negotiation. Hudson testified in Hasan’s case: “The basic principle in these situations . . . is to buy time. . . . [T]he more time that goes on the greater the chances for a peaceful resolution to the situation.” This assumption proved – to use an unfortunate phrase – to be dead wrong.

7. By cutting off water and electricity to the occupied cell block on April 12, the State created a new cause of grievance. The prisoners’ concern to get back what they had at the outset of the disturbance became the sticking point in unsuccessful negotiations to end the standoff before Officer Vallandingham was murdered.

8. On the morning of April14, spokeswoman Tessa Unwin made a statement to the press on behalf of the authorities. Ms. Unwin was asked to comment on a message written on a sheet that was hung out of an L block window threatening to kill a hostage officer. Rather than responding “No comment,” she stated: “It’s a standard threat. It’s nothing new. . . They’ve been threatening things like this from the beginning.” According to several prisoners in L block and to hostage officer Larry Dotson, this statement inflamed sentiment among the prisoners who were listening on battery-powered radios. In the judgment of the officers’ union, in their report on the disturbance:

As anyone familiar with the process and language of negotiations would know, this kind of public discounting of the inmate threats practically guaranteed a hostage death.

When an official DR&C spokesperson publicly discounted the inmate threats as bluffing, the inmates were almost forced to kill or maim a hostage to maintain or regain their perceived bargaining strength.

9. In 2010, documentary filmmaker Derrick Jones interviewed Daniel Hogan, who prosecuted Robb and Skatzes and is now a state court judge. Hogan told Jones on tape: “I don’t know that we will ever know who hands-on killed the corrections officer, Vallandingham.” Later Mr. Jones asked former prosecutor Hogan: “When it comes to Officer Vallandingham, who killed him?” Judge Hogan replied: “I don’t know. And I don’t think we’ll ever know.” Nonetheless, four spokespersons and supposed leaders of the uprising have been found guilty of the officer’s aggravated murder, and sentenced to death.

Who Did Kill Officer Vallandingham?

With the help of Attorney Niki Schwartz, three prisoner representatives accepted a 21 point agreement and a peaceful surrender followed. The agreement stated in point 6, “Administrative discipline and criminal proceedings will be fairly and impartially administered without bias against individuals or groups.” Point 14 added, “There will be no retaliatory actions taken toward any inmate or groups of inmates.”

The raw intent of the State to violate these understandings was made clear during and immediately after the surrender. Inmate Emanuel Newell, who had almost been killed by the rebelling prisoners, was carried out of L block on a stretcher. A trooper asked him, What did you see Skatzes do? Newell and John Fryman, who had been assaulted by the insurgents and left for dead, were put in the Lucasville infirmary. Both were approached by representatives of the State. Fryman remembered:

They made it clear they wanted the leaders. They wanted to prosecute Hasan, George Skatzes, Lavelle, Jason Robb, and another Muslim. They had not yet begun their investigation but they knew they wanted those leaders. I joked with them and said, “You basically don’t care what I say as long as it’s against these guys.” They said, “Yeah, that’s it.”

Newell named the men who had interrogated him: Lieutenant Root, Sergeant Hudson, and Troopers McGough and Sayers. According to Newell:

These officers said, “We want Skatzes. We want Lavelle. We want Hasan.” They also said, “We know they were leaders. . . . We want to burn their ass. We want to put them in the electric chair for murdering Officer Vallandingham.”

With the same motivation, the prosecutors pursued a more sophisticated strategy. ODRC Director Reginald Wilkinson put it this way in an article that he co-authored with his associate Thomas Stickrath for the Corrections Management Quarterly:

According to Special Prosecutor Mark Piepmeier, his staff targeted a few gang leaders. . . . Thirteen months into the investigation, a primary riot provocateur agreed to talk about Officer Vallandingham’s death. . . . His testimony led to death sentences for riot leaders Carlos Sanders, Jason Robb, James Were, and George Skatzes.

The so-called primary riot provocateur was prisoner Anthony Lavelle, leader of the Black Gangster Disciples, who, along with Hasan and Robb, had negotiated the surrender agreement.

How did the State induce Lavelle not only to talk, but to say what the prosecution desired?

During the winter of 1993-1994, Hasan, Lavelle, and Skatzes were housed in adjacent cells at the Chillicothe Correctional Institution. On April 6, 1994, Skatzes was taken to a room where he found Sergeant Hudson, Trooper McGough of the Highway Patrol, and two prosecutors. This was the third such occasion and, as twice before, Skatzes said that he did not wish to continue the interview, and turned to go back to his cell in the North Hole.

What happened next, according to Skatzes, was that Warden Ralph Coyle entered the room and said that Central Office did not want Skatzes to go back to the North Hole. Skatzes protested vehemently that this would make him look like a snitch. Coyle was adamant and Skatzes was led away to a new location.

Back in the North Hole, Lavelle reacted exactly as Skatzes feared. Lavelle wrote a letter to Jason Robb that became an exhibit in Robb’s trial: “Jason: I am forced to write you and relate a few things that happen down here lately. With much sadness I will give you the raw deal, your brother George has done a vanishing act on us. . . . On Wednesday, April 6, 1994 G. said about 8:00 a.m. that he had a lawyer visit . . . . Now to be short and simple, he failed to return that day. Today they came and packed up his property which leads me to one conclusion that he has chose to be a cop.”

Later, Lavelle himself testified that he turned State’s evidence because he thought he would go to Death Row if he did not. This was an accurate assessment. Prosecutor Hogan told a trial court judge at sidebar that his colleague Prosecutor Stead had told Lavelle, Either you are going to be my witness or I’m going to try to kill you. According to the testimony under oath of prisoner Anthony Odom, who celled across from Lavelle at the time Lavelle entered into his plea agreement, Lavelle “said he was gonna cop out [be]cause the prosecutor was sweating him, trying to hit him with a murder charge . . . . He said he was going to tell them what they wanted to hear.”

Lavelle was understandably concerned that the prosecutor might hit him with a murder charge because it is overwhelmingly likely that it was, in fact, he who coordinated Officer Vallandingham’s murder. I have laid out the evidence in my book and in an article in the Capital University Law Review. Briefly,

- Three members of the Black Gangster Disciples stated under oath that Lavelle tried to recruit them for a death squad after Ms. Unwin’s statement on April 14;

- Sean Davis, who slept in L-1 as Lavelle did, testified that when he awoke on the morning of April 15, he heard Lavelle telling Stacey Gordon that he was going to kill a guard to which Gordon replied that he would clean up afterward;

- The late James Bell a.k.a. Nuruddin executed an affidavit before his death to the effect that Lavelle had left the morning meeting on April 15 furious that the Muslims and Aryans were unwilling to kill a hostage officer;

- Three prisoners saw Lavelle and two other Disciples come down the L- block corridor from L-1 and go into L-6, leaving a few minutes later;

- James Were, on guard duty in L-6 and thereby an eye witness to the murder, went to L-1 when he learned that the action had not been approved by other riot leaders and knocked Lavelle to the ground. Willie Johnson and Eddie Moss heard Were explicitly blame Lavelle for the killing;

- Two older and, in my opinion, reliable convicts, Leroy Elmore and the late Roy Donald, say that on April 15 Lavelle told each of them in so many words that he had had the guard killed.

Unlike prisoners who testified for the State, the twelve men whose evidence I have summarized received no benefits for coming forward and, in fact, risked retaliation from other inmates by doing so. No jury has ever heard their collective narrative.

What is to be Done?

So, what can we do?

The first task is to make it possible for the men condemned to death and life in prison to tell their stories, on camera, in face-to-face interviews with representatives of the media.

For twenty years the State of Ohio, through both its Columbus office of communications and individual wardens, has denied requests for media access to all prisoners convicted of illegal acts during the 11-day occupation. Indeed, in the 11-day occupation itself, one of the prisoners’ persistent demands was for the opportunity to tell their story to the world. In telephone calls to the authorities during the first night of the occupation, prisoner representatives proposed a telephone interview with one media representative, or a live interview with a designated TV channel, in exchange for the release of one hostage correctional officer. At 7:00 a.m. on Monday, April 12 the prisoners in rebellion broke off telephone negotiations, demanding local and national news coverage before any hostage release.

In the late morning of April 12, George Skatzes volunteered to go out on the yard, accompanied by Cecil Allen, carrying an enormous white flag of truce. The men asked for access to the media already camped outside the prison walls.

When on April 15 and 16 the prisoners released hostage officers Darrold Clark and Anthony Demons, what did they ask for and get in return? The opportunity for one spokesperson, Skatzes, to make a radio address and for another, Muslim Stanley Cummings, to speak on TV the next morning.

Now the Lucasville prisoners are again knocking on the door of the State, hunger striking, crying out against their isolation from the dialogue of civic society. They ask, Why are we being kept incommunicado? What is the State afraid of?

I urge all present not to be distracted by official talk about alternative means of communication. The state tells us that the men condemned to death can write letters and make telephone calls. But the media access that these prisoners seek is the kind of exchange that can occur in courtroom cross-examination. The condemned are saying to us, Before you kill me, give me a chance to join with you in trying to figure out what actually occurred.

These are not homicides like that of which Mumia Abu Jamal is accused or that for which Troy Davis was executed: homicides with one decedent, one alleged perpetrator, and half a dozen witnesses. This is an immense tangle of events. There is no objective evidence except for the testimony of the medical examiners, which repeatedly contradicted the claims of the prosecution. Very few physical objects remain in existence. The medical examiner testified that David Sommers was killed by a single massive blow with an object like a bat. A bloody baseball bat was found near the body of David Sommers. Special Prosecutor Mark Piepmeier ordered the bat to be destroyed.

We need media access to the Lucasville Five and their companions not just to perceive them as human beings, but to determine the truth. George Skatzes and Aaron Jefferson were tried in separate trials and each was convicted of striking the single massive blow that killed Mr. Sommers. Eric Girdy has confessed to being one of the three killers of Earl Elder, using a shank made of glass from the mirror in the officers’ restroom, and slivers of glass were found in one of the lethal wounds and on the nearby floor. Girdy has insisted under oath that Skatzes had nothing to do with the murder; yet the State, while accepting Girdy’s confession, has not vacated the judgment against Skatzes. Hasan and Namir were found Not Guilty of killing Bruce Harris yet Stacey Gordon, who admitted to being one of the killers, is on the street. The trial court judge in Keith LaMar’s trial refused to direct the prosecution to turn over to counsel for the defense the transcripts of all interviews conducted by the Highway Patrol with potential witnesses of the homicides for which LaMar was convicted, and LaMar is now closest to death of the Five. Jason Robb did nothing to cause the death of Officer Vallandingham except to attend an inconclusive meeting also attended by Anthony Lavelle, but only Robb was sentenced to death.

These things are not right, not just, not fair. The men facing death and life imprisonment for their alleged actions in April 1993 need to be full participants in the truth-seeking process. That is why, to repeat, I believe that our first task following this gathering is to make it possible for these men to tell their stories, on camera, in face-to-face interviews with representatives of the media. Journalists, for example from campus newspapers, who wish precise information as to how to request interviews should contact me.

Staughton Lynd 330-652-9635 [email protected]

Comments