A short history of the 1830 Swing riots by Stuart Booth. Farm bosses would receive threatening letters from a fictional “Captain Swing”, and if they didn’t submit to the demands their premises would be attacked.

In early 19th-century Dorset, once the harvest was in, one of the main autumn and winter jobs for farm workers was threshing. By the late 1820s, landowners and farmers had begun to introduce threshing machines to do this work. Large numbers of labourers found themselves out of a job, without the money to buy food, clothes or other goods for the winter months. The final blow was the poor harvests in 1829 and 1830, resulting in hunger, protests and disturbances in many country areas, especially in southern counties like Dorset. The protesters used the name ‘Captain Swing’, a made-up name designed to spread fear among landowners and to avoid the real protest leaders being found out. No doubt it was also chosen, to some extent, as a form of morbid humour that echoed the gallows fate that could await apprehended rebels involved in his movement.1

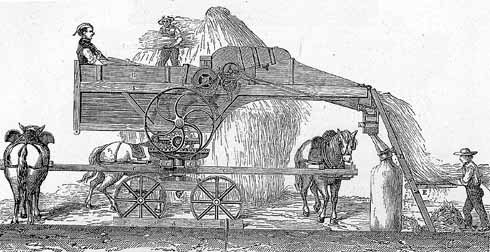

A threshing machine of the type that inspired the Captain Swing riots

The uprisings had started in Kent some time in June 1830 and spread across the south, county by county, into Surrey and on into Hampshire and Wiltshire. By the autumn of 1830, Dorset farmers were being sent threatening letters demanding that wages be increased or at least remain the same. These letters often told farmers and the landowners not to use threshing machines and demanded contributions of food, money, beer or all three. They might be accompanied by hayricks and farm buildings being set alight and the destruction or dismantling of threshing machines.

On 26 November, rioters from Stoke Wake and Mappowder destroyed William Coward’s machine at Woolland. Next day, they demanded money from Christopher Morey, a small farmer and blacksmith. They moved on and later in the day, despite the attempts of vicar James Venables to appease them, they smashed a machine on John Pount’s farm at Buckland Newton ‘with a great noise and blowing of horns’.

The mechanism and construction of such farming machinery is not without significance in this particular case. Threshing machines of that period were made chiefly of wood, the only metal parts being the rotating drum and the iron bars against which the drum forced the harvested crop. In advance of the rioters’ arrival and fearing trouble, Pount’s carpenter had hidden the ironwork in a nearby withy bed. The outcome of this was that when the attackers were later apprehended and put up for trial, a major part of the hearing was taken up with arguments about which of the rioters had revealed the hiding place.

Machine-breaking, especially of the cast iron parts, benefited from some knowledge on the part of the participant, so it is no surprise that another rioter was stated to be a Stour Provost wheelwright, who conventionally undertook machine repairs and so was well placed to become a rebellious machine-breaker.

Among the rioters were men with motives different from those of the labourers. John Dore is the only Dorset farmer noted as actually having joined in a riot. He also kept a beer shop and was accused of fomenting trouble in the interest of extra sales! In fact, such establishments were to become one of several institutions that the authorities blamed for being places where rebellious workers met, were recruited and received instructions. The overall social atmosphere was such that even those only thought to be sympathisers were also charged with holding meetings and encouraging disturbances.

Also in late November, the rioters’ attention turned to one William James, who farmed at Mappowder. James was unpopular on three counts: he came originally from Purbeck, so was an outsider in the Blackmore Vale; he was a churchwarden, so was responsible for administering the parish rate; and he was a large farmer who rented almost half the land in the parish. The rebellious crowd asked him for money, which he refused to give.

At about 8.30 pm on 27 November, a crowd of about twenty reached John Young’s farm at Pulham. He gave them six half-crowns, and his neighbour Matthew Galpin added £2, to persuade them to go away. However, his resentment at the demands and the manner in which they had been made of him ensured that he later gave evidence that helped to condemn four men to transportation to Australia.

Two days later, another crowd attacked Walter Snook, a farmer and a constable at Stour Provost. He made some arrests for machine-breaking and conveyed his prisoners to Shaftesbury. There, the keys to the lock-up could not be found, and local Swing sympathisers actually rescued and released the prisoners.

Before the wild hours of 29 November were over, however, further riots broke out in Castle Hill, Lulworth, Preston, Winfrith and Wool. As before, most of these were aimed at persuading farmers to raise wages. On 1 December a more serious assault took place at Stalbridge and threshing machines were attacked near Sherborne and at Lytchett Matravers. With the coming of winter, however, travel was increasingly difficult for the rebellious crowds, so other than a few isolated arson attempts in early December, the violence in Dorset faded away.

Not only was the name ‘Captain Swing’ widely used by various elements of the protestors, he was also the supposed writer of several letters sent to farmers and others and became known nationally, being first mentioned by The Times on 21 October 1830. Intended to instil fear, the letters usually threatened arson as a reprisal for the cited injustices perpetrated by the recipients. Some letters were general in tone; others were probably the work of disgruntled individuals, seeking to settle a private grudge.

Few of the letter-writers were brought to trial. In addition, it is not known how many letters were real, and which were fake or were created by an agent provocateur. Educated people evidently wrote some, while others show a deliberately illiterate style used in order to preserve anonymity. Relatively few, though, are likely to have been from the labourers themselves. For example: ‘Sir, Your name is down amongst the Black hearts in the Black Book and this is to advise you and the like of you, who are Parson Justasses, to make your wills. Ye have been the Blackguard Enemies of the People on all occasions, Ye have not yet done as ye ought. Swing’. Or more succinctly: ‘Sir, This is to acquaint you that if your thrashing machines are not destroyed by you directly we shall commence our labours. Signed on behalf of the whole, Swing’.

The Swing protests were remarkably self-disciplined and the crowds tended to conduct themselves within the accepted bounds of behaviour, but the parallel and largely nocturnal attacks by Captain Swing and the high incidence of fire-raising during the period of the Swing uprising became a serious cause for alarm. ‘Swing the hayrick burner’ was not only more destructive but much more difficult to apprehend than ‘Swing the protestor’.

These parallel overt and covert activities and the relationship between the two has long been a subject of debate and speculation. Nevertheless, as with many earlier uprisings of working people and even in latter-day liberation and terrorist movements, the physical attacks on property undoubtedly provided additional strength to the demands of the protesting crowds and is a classic example of solidarity of both purpose and action.

In human terms, the downside for the Swing protestors was that throughout England, some 650 rioters were imprisoned, 500 sentenced to transportation (mainly to Australia) and 19 were actually executed.

The Dorset folk musician, Graham Moore, has written a musical drama, Tolpuddle Man, which includes a song called ‘Captain Swing’. One verse of it goes:

The labouring man is on his knees, nowhere can he get hired,

Since new machines that do the work, the farmer has acquired

But how he sweats when he reads the threats on paper morning brings

‘Destroy your gear or else I swear you’ll pay’, signed Captain Swing

All over Dorset, the flames are leaping high

The ricks are burning, who’s the cause?

Captain Swing, not I!

- 1 libcom note: according to historian Eric Hobsbawm they chose the name 'Swing' because cythers or bill-hookers in a row harvesting, cut in unison to the cry of 'Swing!' Thanks to Michael Rosen for informing us of this, from a note in Notes and Queries: a follow-up to Hobsbawm's book Captain Swing.

Comments