Work. A contested word, loaded with millions of synonyms and associations. Hate/love. But for the author Folke Fridell (1905-1984) there was no doubt: there is no intrinsic value to be found in work. It is not a source of pride. During his life he waged a constant war, against work, against the machines, against the bosses, but perhaps also, in his individuality, against his co-workers too.

Fridell, a life-long anarcho-syndicalist, ended up becoming one of the most famous of the Swedish 'proletarian writers', a literary movement which emerged out of the Swedish industrial system in the early 20th century, many of them growing up as statare, agricultural workers who were paid in kind only (comparable with the Anglo-Saxon truck system).

His first books were quickly penned down during breaks at the factory, with the first success being the strongly autobiographical Död mans hand ("Dead Man's Hand, 1946), selling a record 110,000 copies (much thanks to the system of "literary ombudsmen" organized by the Folket i Bild publishing house in order to disseminate affordable literature to the workplaces in the country).

The author at his workplace, seen second to the right

Fridell often drew on his experiences of the manufacturing industry, having entered the world of the textile mill at the young age of 13. As a result, his characters are often factory workers, with themes revolving around their frustration, dissatisfaction, and struggle. Constant is the presence of Taylorism and other metrics that plagued those slaving in the Swedish workplaces at the time, but also a subtle irony, which sometimes may be lost on modern readers.

Other themes addressed by Fridell include the problems of juvenile delinquency and rural depopulation, the possibility of cooperative economy, and he sometimes painted somewhat dystopian images of the future. All his books express his positive view of individual freedom, underscoring the righteousness of rebellion against power and centralization, but are at the same time driven by main characters that are often of a rather timid nature, and stories of failure when they attempt to rectify these problems as individuals rather than as a collective.

Politically, Fridell placed himself on the libertarian end of the spectrum, explaining his life-long syndicalist convictions by saying that "as everyone I came to admire were syndicalists themselves, it was only natural for me to make the same choice". Fridell's first encounters with syndicalism and anarchism came early: after having been approached by the area's log-drivers - an industry where the syndicalists often were the majority union - the textile workers at his mill formed a local federation of the SAC in 1923

In the late 1920s, however, Fridell left the SAC in the late 1920s, along with the whole of his local federation - Lagans LS - disaffiliated in order to join the more "hard-core" Syndicalist Workers' Federation (SWF). This newly formed organization was led by PJ Welinder, an emigrant Swede who, after having served as GST in the IWW in the US, eventually returned to his native country following the defeat of the Emergency Faction. The values espoused by Welinder resonated with Fridell, with the SWF argued against what they saw as a growing bureaucracy within the SAC, as well as increased acceptance and reliance on fixed-term contracts and permanent strike funds, which to their minds meant a less combative and more vulnerable union. The effects of the great depression had severely weakened the federation, and reduced from 6,000 to 3,000 members in 1938, they finally agreed to yet another of the SAC's many offers to rejoin forces.

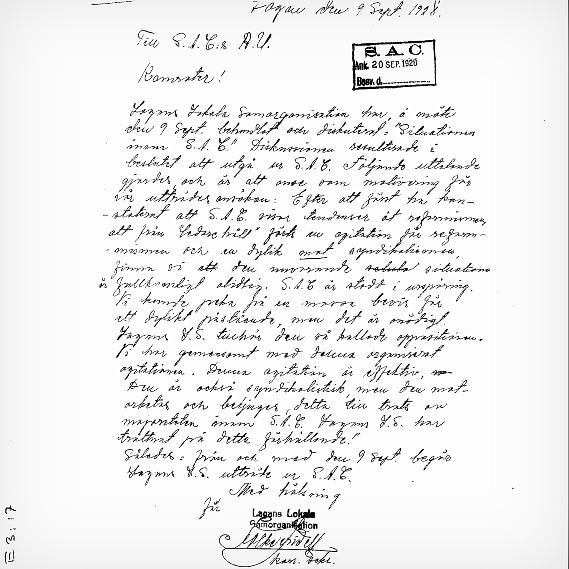

Letter of disaffiliation to the SAC, signed by the secretary of the LS, Folke Fridell

Aside from his literary output, Fridell was also a frequent contributor to debates on ideology, strategy, and tactics, writing on subjects such as collective bargaining, the strength and weaknesses of cooperative strategies, the failure of authoritarian socialism, and so on. Similarly to many of the proletarian writers, Fridell spent a lot of time traveling up and down the country, giving talks for the union and temperance movement alike.

An impressive advocate for proletarian fiction and intellectual self-improvement, he left a lasting impression on the working class of Sweden. Or, as he expressed it in his own words:

"As long as there are proletarians there is also a need for proletarian fiction. I would even go as far as saying that as long as people are downgraded in their work-life, then there must be voices capable of speaking in their language and addressing their cause."

Sources:

https://www.sac.se/cat/Om-SAC/Historik/Biografier/Fridell,-Folke-1904-1985

Comments

Interesting, thanx

Interesting, thanx

Yes really nicely written

Yes really nicely written too. It doesn't look like much of his work is available in English? This book seems to cover some of his works though: https://www.mah.se/english/News/News-2014/Swedish-working-class-literature-is-unique-/

Thanks syndicalist, Jared.

Thanks syndicalist, Jared. Glad it was of some use.

No, not much translated at all, but a good substitute is Stig Dagerman, who has had quite few of his titles translated into English. I think his daughter is involved in some of this, and that she has posted about it in libcom's Dagerman article. Dagerman was more involved in the explicitly anarchist organizations, and also the early SUF. See http://dagerman.us/

Highest of all, though, I rate Jan Fridegård, who - like many other prominent-to-be authors - published his first stories in the still-running magazine Brand. I know some of his books in the Lars Hård series (I, Lars Hård for example) are available in English. This are terse, sparse, and harsh reflections on the life of a "statare" (like Fridell), migrant labourer, hobo, and writer.

In the article Jared linked to there is mention of Kristian Lundberg, not a new writer by any means, but one of the people in the new wave of Swedish workers' literature. The reality now is not about statare, but flexible precarious workers. It was made into a film recently, which I think might be available in English even though the book isn't.

Yarden Trailer

Folke Fridell speaking at the

Folke Fridell speaking at the 1960 congress of the SAC (color film, no sound)