The Call Centre Diaries will be a semi regular series detailing my experiences as a precarious worker. To kick things off I’m going to share my experiences of working at Manpower, a major UK recruitment agency. Hopefully this won’t just touch on my experiences as a worker but also how the environment fostered in the kind of companies that thrive in economies structured around temporary contracts is adversely affecting the lives of both their own workers and the unemployed they are supposed to be finding work for.

Fit For (Neoliberal) Purpose

The first thing any unemployed worker needs to know when they ring a recruitment centre like Manpower is that they are not staffed by “recruitment professionals” or “recruitment experts” (whatever that even means). In all likelihood they have a similar makeup to just about any other call centre. Just people like me working for minimum wage, doing shift work. No expertise is needed, as this is fundamentally grunt work, complete with the condescendingly inane job title of “Telephone Recruitment Consultant” (TRC). Most of the staff at Manpower were college students working part time shifts or hours oriented around their education schedule. As a single person living alone in a housing association flat on an housing estate in the centre of town, I was in the minority. Most workers either shared houses or lived with their parents or partners. I took the job for the same reason thousands of people each day called in to apply for the jobs we advertised for: it was the first thing that came up and I needed to pay the rent sharpish.

Despite its risibly grandiose title, Manpower’s “National Recruitment Centre” was just like any other understaffed call centre. The small office housed a couple of hundred workers at a time and was located on the third floor of a city centre high street in Newcastle. The layout consisted of massed rows of “Telephone Recruitment Consultants”, about 10 each to a row if memory serves. Considering the enormous amount of calls received by recruitment agencies in the current economic climate, and when taking into account the fact that all applications for many of the positions advertised by local branches were routed through to this modest office, it was immediately obvious to me that this centralization was going to result in overworked staff and inadequate response time. A lot of call centres I’ve worked in have had similar layouts to this. Some of the more cosmetically agreeable ones might grant their workers the veritable luxury of a “pod” set-up, to ensure that we don’t feel like we are in high school assembly and increase our productivity. A “pod” consists of four workers sitting around a conjoined table and is usually found in larger offices with a bit more space. We didn’t get pods. Fuck pods anyway. Tables, mate.

In a highly unnecessary nod to social hierarchy, management permanently sat on the first row, with “the campaign team” – a somewhat mysterious subsection of the workforce, ostensibly made up of people who weren’t doing the same work as everyone else, but also weren’t bosses either, located just round the corner of the L Shaped room. There was a reception area and some smaller rooms for “one to ones” (face to face interviews with potential new staff members, performance reviews etc). There was also a kitchen, laughably inadequate in size that we could spend our unpaid half hour breaks in, provided it wasn’t already completely crowded. As a side note, I feel compelled to point out that they provided a giant communal bag of Tetley tea bags for free, a fact constantly and somewhat bizarrely referred back to by management as an example of how lucky we all were to work there if we raised any objections to working conditions.

It goes without saying that attempting to run this kind of operation on the cheap, staffed by workers on the lowest wage possible under law working in highly stressful conditions simply to pay their bills or save some money up to go off to university, makes the whole operation inherently unfit for purpose.

But then, when you think about it, of course its fit for purpose – the recruitment industry isn’t designed to create more employment at all, its designed to receive weighty contracts from its clients who in turn they provide a transient, demoralized workforce for low in confidence, thankful for even the most unrewarding work amidst the hell of harassment from the dole office or shame of being out of work. Why would any of us ever want to add to all this stress by organizing at work? Therefore, why would anyone want to speak out when the threat of having your hours cut due to your zero hours contract hangs over you every day?

“Us” vs “Them”: English Jobs For English Names

My training was handled entirely by a fellow worker who I was “buddied up” with (I know, right?) at the start of training. They talked me through the use of software and the workflow process. Not once did a single manager take any part in the training process, other than to deliver an arse-clenchingly insincere induction session during which we were treated to the usual bullshit corporate origins myth – to cut a long story short, a bunch of rich white blokes met each other playing golf and decided to provide each other with cut-price labour. And now here we are. Obviously, the extra strain of having to train a new starter on top of completing all the other work we had to do meant that the thoroughness of each individual workers initial training could differ wildly.

Most people learnt on the job through trial and error. Nothing wrong with that of course. That’s a pretty good way to learn stuff. But it also means it’s incredibly easy for people to want to take the easy option: the job is already stressful enough as it is without having to add anything even remotely more difficult to it. But, as I’ll detail in more depth shortly, when you combine this understandable need to avoid extra workload with the prevailing atmosphere of aggressive meanness towards benefits claimants and immigrant workers, it often translated into lazy classism, xenophobia and even more depressingly, explicit racism.

The nature of the work itself didn’t exactly help. Each day the first task for each TRC, after having logged onto their computer system, was to print off a spread sheet containing the names and contact details of candidates who had applied for a particular position, call those people, inform them about the job and conduct a telephone interview with them. Every position was, as you might expect during a recession, hopelessly oversubscribed. The names were usually alphabetized, which made the entire process even more random than you might imagine – people who had previously applied for a position and performed well at a previous telephone interview stage of the process, for example, were not automatically kept in mind for a similar position in the future. Instead, they were simply added to a monolithic block of names.

Just as I begun to get used to this process I began to realize a culture had developed amongst some members of staff whereby the “recruitment process” revolved around whether the pronunciation or spelling of candidates’ names were considered sturdily Anglo-Saxon enough to deserve a phone call on that day. One of my first arguments with a fellow worker was sparked by me challenging their refusal to call anyone with a “foreign sounding” name, irrespective of whereabouts they appeared on their list, until they had first phoned anyone with an English name. Most of the areas we were recruiting in “on behalf of our clients” were in pretty densely multi-ethnic working class communities such as those in areas like my hometown of Manchester, Nottingham and Bradford. This attitude was commonplace amongst a slim majority of the workforce. The outcome of any “campaign” could become acutely racialized depending upon who was assigned to it.

The majority of BME applicants in many of the most deprived parts of these towns and cities, which inevitably yielded the most job applications, were systemically prejudiced against from the beginning of the recruitment process due to the name on their birth certificate. Polish and West African names would often be most likely left til last. Gaelic Irish and Gallic Scottish names were often deemed worthy of passing over too. After I’d raised the issue during a one to one session and nothing came of it, I simply resolved to try and call people out on it whenever it occurred.

Added to this everyday racism was the other most prominent form of social bigotry on display each working day. Considering recruitment consultants are likely to have as much contact with unemployed people as just about anyone else, there wasn't just a widespread lack of empathy for those we were supposed to be impartially interviewing over the phone, but many staff displayed total disgust towards anyone out of work for a period of longer than a few months. It became downright tiring for me and any fellow workers who were attempting to shift the lunch (half) hour debates from the terrain of claimants bashing to class struggle. It seemed clear to me that this has as much to do with a lack of self-aware class consciousness as it does with any form of real-world class composition: the vast majority of these working class employees didn't just view “unemployed” as analogous to “underclass”. They’d also become convinced that their own interests as employed workers were at best in opposition to the interests of the jobless, at worst that those claiming benefits were a direct attack – through supposed benefit fraud and idleness – on their own chances of social progression. So weirdly, despite being privileged by the racism of the recruitment process, the otherness of any white English unemployed candidates was still emphasized even if they didn't have to deal with racism. Unemployment was still considered an impassable point of difference that separated “us” from “them”.

Outside of making “proactive” outbound calls to a list of applicants, and despite the fact we were woefully understaffed, we were also expected to handle the endless inbound calls that were received each day. Most often, these were calls from people calling in to either make an application or checking on the status of their previous applications. These calls tended to be generated precisely because the policy of the recruitment centre was to conduct a telephone interview process then book the successful candidates in for face to face interviews at local branches around the country during the same call. Yet those who were deemed unsuccessful were fobbed off with a line in the call script that informed them “if you have not received a response in x amount of time, please presume your application has been unsuccessful.” As those of us who have been unemployed for any length of time in the last few years are already acutely aware, the only way to get a concrete response out deliberately labyrinthine and evasive recruitment agencies is to contact them again directly and persistently. The sheer numbers of applications crossed with the inadequate number of staff meant that it would have been impossible to respond to candidates directly informing them if they hadn't got the job or to provide polite and encouraging feedback. This was routinely the most harrowing part of the job. I regularly took calls from audibly distressed people either on the verge of or actually in tears, people feeling suffocated by the ever increasing economic and psychological burden being inflicted on the unemployed.

The clinical and unsympathetic detachment fostered through the nature of the immaterial labour being carried out by the workers in call centres like Manpower’s directly affects the well-being of the unemployed. Those seeking work have their suitability for a particular position arbitrarily decided upon by a telephone recruitment consultant who is bored, stressed and disinterested by the mind-numbing reality of their own work. Not to mention often possessed of their own set of prejudices. It’s very difficult to work for minimum wage in an anxiety inducing job where your every call is ruthlessly monitored without eventually succumbing to the kind of short cuts and emotional disengagement necessary to just get through the day without either losing your job or mind. Personalization and empathy become far more difficult when you are under an economically different yet psychologically similar form of stress as those whose lives you are affecting by your actions. Detachment becomes the norm.

We All Live Inside a Kafka Novel

The on-going emotional pain and mental stress, the grim certainty of being pummelled by the DWP each day, or the endless anxiety of the precarious labour market we now inhabit was completely erased through a process of institutional and cultural dehumanization. It’s a process which has been exacerbated by the atomization of information and communication technology, which employers can handily use to ensure that just about every interaction becomes as depersonalized as possible. This becomes even more pernicious when combined with neoliberalisms successful establishment of the unemployed as an enemy within. Some of my fellow workers who bought into this rhetoric used the recruitment process to further punish those with the temerity to be out of work. I had a particularly rage inducing run-in with one colleague who, upon viewing some poverty porn shite on Channel 4 the previous evening, decided that anyone who had been on benefits for longer than two months was clearly unsuitable for an admin position because “if they really wanted work they’d have found some by now. They’re just fucking workshy”. This is the kind of perverse subjectivity that dictates whether or not you’ll even get to the face to face interview stage.

This demonstrates just how successfully the austerity agenda and demonization of the working class unemployed and immigrant workers has ingrained itself in the culture of the contemporary immaterial labourer. This particularly affected the applications of those who did not speak English as a first language or, as I've already recounted, even anyone without a solidly “British” (read: “white and English”) surname. In fact, the experience of the candidate throughout the whole process and the crucial need for empathizing with those seeking work were never referenced once during any induction, training session or conversations with management. Contrastingly, the Kafkaesque obsession with always filling up the available interview slots as quickly as possible, with the least amount of fuss for our numerous clients – companies like Eon, Npower, SKY and Direct Line – was constantly pushed.

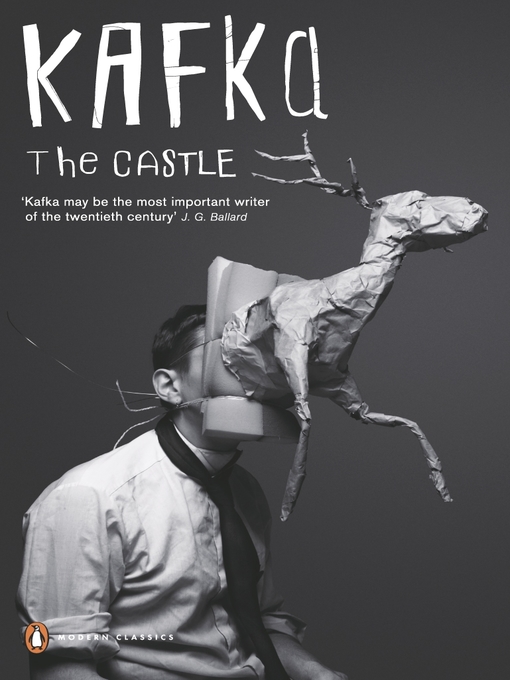

Those company names bare closer scrutiny. I name checked Franz Kafka just there, largely because I don’t think I've read any contemporary fiction that comes as close to nailing the inherent absurdity of contact/call centre work as things like The Castle or The Trial do.* There are few things more dispiriting than sitting for 7.5 hours a day recruiting for positions with the aforementioned companies . I’ve heard anecdotes from numerous friends, acquaintances and comrades from various different parts of the country alleging that all of the above are liable to treat their workers like shit, and nearly all of them were offering similarly precarious work at similarly exploitative rates of pay to my own (Manpower offered a minimum wage and unpaid half hour lunch breaks). Even having said all of that, most wages for our clients were in the region of a quid or more an hour than we were getting paid to “recruit”. There was something mildly masochistic about recruiting for a job which was virtually identical to my own but with slightly better pay and incentives.

So, yeah. We live inside a Kafka novel now.

Before he jumped the shark entirely and starting harping on about Vampire Castles and “beating the anarchists”, Mark Fisher came to a similar conclusion. By which I mean, y’know, I read him and thought he was probably right. He also made some good points about how vacuous and punitive forms of corporate process have encroached into every pore of daily life. He called this market Stalinism, a development which encapsulates the existence of shit like “Background Checks” to use an example from my time at Manpower. Background Checks are a separate form that must be filled in by the TRC if a candidate has previously worked for a company. The form must then be sent off to the employer in question to ascertain whether or not the candidate is welcome to return. There is now a whole tranche of the working class who survive on securing work with the same company they were working for during their previous temporary contract, enabling employers to build up a pool of workers who are eternally employed precariously. Loyalty to the company is ensured by them being viewed as the most reliable and fair employer, the company who will constantly give you another opportunity when your former contract is up.

The implications of this kind of recruitment are obvious. The worker must be thankful for the continued opportunities. “We’re all in this together”. Best not kick up a fuss when you get that contract tweaked lest you be seen as a troublemaker come the next round of “projects” or “campaigns” that the company will be recruiting for. I can’t imagine workplace organizing is going to get you many browny points the next time the employer receives a background check request from Manpower, that’s for sure. Checks would often take an inordinately long amount of time to come back to us from the employer, sometimes resulting in the positions becoming filled by candidates that had applied long after the people who were still waiting on their background checks to return, which led to understandably pissed off phone calls which would in turn increase the stress of those of working in the recruitment centre. We received no objection handling training or any guidance on how to deal with distressed candidates during my time there.

Unions: “What Do They Actually Get Up To?”

As I’ve already mentioned, for some members of staff the prejudices I’ve described above weren’t especially conscious ones. Sure, there were a few irremediable ringpieces who were prime Britain First fodder, but largely it came down to basic cultural hegemony. A lot of the workforce were under 21 and had mostly inherited the ideology of their parents or mates, as most of us do at that age. The Daily Mail was by far the most accessed online source of news in an office working in an industry that has virtually zero history of struggle or workplace organizing, not to mention an inherantly transient workforce. A total lack of identification or sympathy with the very working class which the majority of employees within the contact centre also belong to is only reflective of how wide reaching and thoroughly entrenched the scapegoating of benefits claimants and BME communities has become for modern capital. As much smarter people than me have pointed out, it’s essential to neoliberal political economy as a whole.

Anyway, what I’m getting at is that in most conversations I had with my fellow workers whose prejudices were simply inherited or pragmatic, they would often recognize this and attempt to behave differently, until the institutionalized targets and structuring of work itself meant that it was far easier to regress back to habit. I had some positive results when challenging people on racist behaviour, especially with younger members of staff who seemed happy that someone a bit older (they mistakenly believed management would be more amenable to the suggestions of over 18’s) was publicly making points they had silently agreed with. In an industry as under-organized and lacking in an abundance of concrete past victories to point to in an effort to raise class confidence, these initial conversations were a valuable starting point for further discussing other workplace issues.

While I was encouraged by some of the more positive responses I received from other members of staff, these episodes also served to emphasize how ludicrous the delusions of reformist trade unionism are. Manpower recognizes no union, yet it has, in the words of one supervisor, “a working relationship” with UNISON. “Aye, I bet you do”, I thought. The truth is that the labour aristocracy has been completely bypassed by the advent of immaterial labour. We all know that one day “General Strikes” and A-B marches are empty outmoded gestures. But in highly precarious, stress saturated environments like call centres, they make even less practical sense in terms of workplace militants using them as some sort of example of how to effect change. We have to recognize that we are virtually starting from scratch.

That Spirit Of 45 shit is not going fly amidst the crushing everyday pressure of capitalist realism that permeates the workplaces that most of us find ourselves in these days. More of us now work in call centres than ever worked down the mines. Yet the collective memory of generations of class struggle has been bulldozed successfully enough that one of the most intelligent and well-read 19 year olds in the entire office, now studying sociology at Goldsmiths, asked me with a slight tone of embarrassment what it is a trade union actually does. “Obviously I know what they are. But what do they actually get up to? “This is a smart, politically aware young person already identifying as a feminist with a keen sense of injustice. But their question was a bloody good one considering these mass industries have no mainstream union presence whatsoever in most cases. “Working relationship” just means the game is rigged.

Of course, we think we’ve got the answer to all this. We might reckon we’ve got a pretty good idea of how to get there too. Workers taking control of their own affairs and collectively bypassing the bureaucracy of the paid union official. Taking direct action to settle grievances and improve conditions without the need for representation or mediation. But when we are starting from such a beleaguered position of atomization and depressed class consciousness, it can seem like the most daunting thing in the world to try and instigate this. Even the numerous recent examples of successful workplace organizing we can point to as militants can seem distant, something other people do that can never happen in our own workplaces. I’ll be returning to the theme of how we attempt to reverse this situation in future articles.

In the second part of this series, I’ll be taking a look at how my time in the recruitment industry affected my own physical and mental health. I’ll also be detailing the behaviour of the bosses in this kind of environment and detailing a disciplinary procedure taken against me by them for “unsatisfactory call handling time”.

*Kafka’s really good on the absurdity of toil actually, check the opening few pages of his short story Metamorphosis for more on this. Actually, just read the whole story if you haven’t already, its fucking great.

**For far more articulate analyses of the relationship between work under capital and stress, I implore you to check out Sometimes Explodes

Comments

I've read libcom for years,

I've read libcom for years, but have never felt compelled to register for an account so I can comment until now. Mate, this blog is brilliant. I worked in many different call centres for nearly a decade, and this is such an accurate account of what it's like. I worked in them before I was 'political', and had a nervous breakdown and was in hospital for a wee while (this was many years ago). Looking back on that time now, I'm fairly certain that my work was one of the main contributors to the state of my mental health.

The racism you speak of wasn't just shared amongst my co-workers but was also institutional. I remember when I worked in one for a major bank, if someone with an 'African' sounding name or accent called to transfer money to someone else with a similar name, we had to pretend that we'd done it but then report it to another team who would carry out additional checks.

I remember one odious place where small bonuses weren't awarded on individual performance, but on the teams, so if one person was a bit crap, or was off sick ever, the rest of the team hated them for it.

But before I knew what 'workplace organising' was though, there were some tiny glimmers of hope. I remember, for example, this guy who I worked with (who was so lovely, and I'm pretty sure kept me as sane as it was possible to be), me and him would cover for each other, and would text each other if we were going to be late, and log in for each other (done by typing a code personal to you into your phone, which telling someone else was gross misconduct) so we wouldn't get bollocked, risking ourselves to protect the other. Those teeny acts of solidarity, which seem so tiny and just basic human decency, took on a whole new significance in an otherwise mountain of shit.

Wish you'd worked there when I did, ha. Solidarity with you mate, and look forward to reading the next one :)

Cheets mate! Ive not written

Cheets mate! Ive not written anything for years and Ive been a bit nervous about posting, im really chuffed it chimes with your experiences x

Great response Vert, and good

Great response Vert, and good to have you on the forums

So, funnily enough, this is the exact example I always use when people tell me 'there's no solidarity in my workplace'.

I used to work in a school as a teaching assistant and we had to sign in every morning and a similar system developed naturally amongst us TAs - and I actually think acts like that have a real power in building up a sense of trust in each other. When, a bit later on, we engaged in some outward solidarity, I look back at our little tick-in scheme as part of what got the ball rolling.

Yeah, awesome piece. It's

Yeah, awesome piece.

It's said that unions suit capital because they police the working class. The idea being supposedly that workers without the discipline of their union would take matter into their own hands, which would be harder for capital to manage.

Whilst that's obviously the case in particular circumstances, it doesn't explain why hundreds of thousands of workers in call centres, retail and the service industry aren't choosing to settle grievances through their own forms of sabotage or aggression. Perhaps they are (there are obvious reasons for keeping quiet about that), but it isn't the impression I get. A kind of morbid, resigned compliance seems to be the order of the day.

Thanks for writing/posting,

Thanks for writing/posting, this is an excellent blog and I look forward to more!

On this point:

orkhis

basically we're in a different socio-economic climate now in the UK then when libertarian socialists/the ultraleft were making that critique. In US auto plants in the 40s, UK factories in the 50s and 60s and Italian industry in the 60s and 70s that most definitely was the case.

Now we are in a period where the working class is not on the offensive, we are on the defensive, and often just not struggling at all in any collective way. Without militant class struggle there is no need for the policing function of the unions, so you can normally only see it in highpoints of class struggle (like the recent wildcat Sparks campaign, for example which was denounced by the union).

Back to the original post and the author, don't know if you have seen it but my favourite bit of call centre worker sabotage was posted by another libcom user:

http://libcom.org/library/worker-sabotage-financial-services-call-centre

Ach Steven that story you

Ach Steven that story you linked to is great.

I remember when I was working at the bank call centre, we were allowed a certain amount of money a day which we were allowed to award customers who were complaining (e.g if someone was really kicking off about how long they had to wait to get through or something, we could credit their bank account with a bit of money), and me and a couple of others did what we called 'a Robin Hood-er'. When someone rang the call centre and we put their account details in the system, what we saw on the screen was essentially a statement - how much was in their account(s) and recent transactions. If someone was rich we never gave them a penny, but if some skint single mum (or whoever) called up just to check their balance, and we just saw DWP payments crediting the account and nowt else, and a balance of £30 or whatever, we'd instantly be like "We are SO sorry you waited so long to get through today/that your cheque book didn't arrive in time - to apologise for the inconvenience we've just credited your account with £20,". We couldn't do it a lot, but a couple of times a day we'd just bung some skint people a few tenners, often to their bemusement!

I know it's pretty small in the grand scheme of things but I like to think we made a few people's day by our teeny redistributions!

There's probably a million stories of tiny acts of sabotage like that, shame we'll never get to hear about all of them....

verticillatas wrote: Ach

verticillatas

that's also brilliant!

well we try to host as many of them as we possibly can here: http://libcom.org/tags/sabotage

if you could flesh yours out a tiny bit, add a bit about when it was, where it was, how long you worked there, how big was the company, what was your team like etc then you could add it to the library as well as it deserves its own entry! (Just click submit content - library)

Wow, I'll have to sit and

Wow, I'll have to sit and have a read of all those.

Ok, I'll try and have a stab a bit later, thank you :)

verticillatas wrote: Wow,

verticillatas

excellent, cheers!

That's another great story,

That's another great story, Vert.

When I used to scan groceries as a teenager, if I saw someone was paying with a benefits card, I would just conveniently not scan certain items - I didn't particularly view it as sabotage, just my own little wealth redistribution program.

The store was also open 24-7 and the CCTV was piped into the store manager's office, so when you were working late and the manager wasn't there, a sizable number of the staff used to just walk around doing a bit of "shopping" for the week. That was also part of the program.

verticillatas wrote: I

verticillatas

Just to reiterate what others have said, that is a great story!

Enjoyed the post and the

Enjoyed the post and the other stories. Solidarity