California dreaming turns to California nightmare as decades of agribusiness, real estate development and exploitation of migrant workers take their toxic toll. Gifford Hartman takes us on a guided tour of the Golden State's darkside.

I should be very much pleased if you could find me something good (meaty) on economic conditions in California [...]. California is very important for me because nowhere else has the upheaval most shamelessly caused by capitalist centralization taken place with such speed.

- Letter from Karl Marx to Friedrich Sorge, 1880

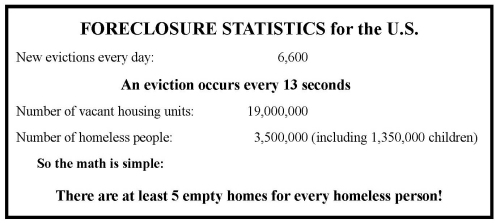

This centralisation has continued with such a velocity, right up to the present, that conditions in California are so overripe they are toxic. While despoiling both the natural and the built environment, capital has also achieved levels of productivity and the capacity to expand use values never before imagined. This overcapacity is in glaring contrast to human needs that are increasingly going unmet; capital's inability to expand exchange-value makes superfluous whole sectors of the working class. California's Central Valley is where these conditions have become most toxic; homes sit vacant alongside the squalor of the newly homeless who fill to overflowing the burgeoning tent cities and shanty towns. This upheaval pulls the veil of capitalist mystification aside and reveals the real conditions, as these numbers for the entire United States show:

See references for statistics in footnote1

Shantytown USA

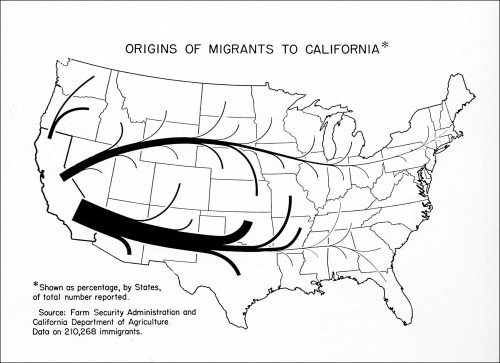

These toxic social relations demonstrated their full irrationality in May 2009 when banks bulldozed brand new, but unsold, McMansions in the exurbs of Southern California.2 Across the US people driven to homelessness are finding shelter beds unavailable as shelters are stretched beyond capacity; St. John's Shelter for Women and Children in Sacramento, California's capital, turns away 350 people a night.3 Sacramento became internationally known when its tent city appeared in news media around the world. When California Governor Arnold Schwarzenegger and the Sacramento Mayor made plans to evict the tent city, the latter justified it by saying ‘They can't stay here, this land is toxic.'4 Although they occur across the US, California is where most new tent cities are appearing.

California's Central Valley: Toxic Heartland along Highway 99

And so, for all the bravado about the state's leading industry [agriculture] – about the billions of dollars that it adds to the economy and the miracles of production and technical ingenuity that it has accomplished - California's farming is on the way out, as the rising value of its soil produces more in [real estate] lots sales than in cotton, cattle, or almonds.

- Gray Brechin, from Farewell, Promised Land5

For data sources see footnote6

California's Central Valley is 720 km long and 80 km wide, sitting between the Sierra Nevada and Coast Range mountains. The two main rivers are the Sacramento and the San Joaquin, going through the northern and southern parts and giving names to the two sections of the valley; they join in a massive delta that flows into the San Francisco Bay. It is the most productive agricultural region in the world. It is also where, since the 1970s, development has been paving over some of the Earth's most fertile soil to build massive tract-style suburban and exurban housing. The Valley probably has more foreclosed homes than anywhere else in the world; some parts have historically had the lowest wages in the US and some of the highest rates of unemployment. The town of Arvin, in the southern end of the Valley, has the dirtiest air in the US.7

Image: Governor Schwarznegger at Sacramento's tent city, 18 March, 2009

Toxic Tour

Highway 99 runs North-South through the heart of the Valley. Sacramento is the northern hub and is surrounded by unplanned suburban sprawl that has replaced farm land. Travelling South along Highway 99 there is a long string of suburbanity: shopping malls; automobile dealerships; companies selling construction equipment, tractors, earth movers, backhoes, etc.; recreational boat dealers; endless rows of tract homes; office parks; billboards; and bridges over rivers and parts of the delta.

The next big city is Stockton, with a deep-water port that connects major rivers with the delta, the bay, and trans-Pacific trade; it is an important shipping centre. It was recently given the inglorious distinction of being called the ‘#1 Most Miserable City in the U.S.' by Forbes magazine.

Continuing south there is more of the same American consumer culture: malls with their massive parking lots; churches and even a huge Christian high school in the town of Ripon; railroad tracks and changing yards running alongside 99; and tall grain silos and food processing facilities, many abandoned. Modesto is the next major city and it is notorious for being the #1 city in the US for car thefts, as well as being #5 on the Forbes list for Most Miserable Cities. It is surrounded by fertile farmland that was built over during the housing boom to create more affordable housing for commuters from as far away as Sacramento, Fresno and even for those willing to endure a drive of over two hours each way to the Bay Area.

Merced has the second highest ‘official' unemployment rate of any US city at 20.4 percent.8 Along Highway 99 there are the same chain stores that could be found anywhere in the country. Juxtaposed with this is the agricultural industry: fields, orchards, and livestock pens along the highway, as well as dealers of farm machinery, tractors, and livestock trailers. There are also plentiful irrigation canals that move water from the wet North to the Valley's dry South. Much of the industrial infrastructure is rusting away and abandoned, many plants with huge ‘for sale' signs on them.

Fresno is California's fifth largest city with a population of 500,000. It is the hub of the southern end of the valley and it always seems to be in a haze of brown smog, especially during the stiflingly hot summer months. It is the ‘Asthma Capital of California', affecting one in three children9 It is also the most productive and profitable agricultural county in the US and, until recently, was also home to three large tent cities downtown, as well as other smaller encampments.10 The first tent city on Union Pacific railroad property was evicted in July 2009. It was literally toxic because sludge was discovered oozing out of holes in the ground in the summer of 2008, possibly because it had once been a vehicle repair yard. Another, called ‘New Jack City' after the 1990s film about drug gangs, earned its nickname because it has already had two murders. The third has many shanties built with scavenged wood, and is called ‘Taco Flats' or ‘Little Tijuana' because most residents are Latinos who came to the area looking for agricultural jobs. The three-year drought has severely limited the number of crops being planted, reducing the amount of work.

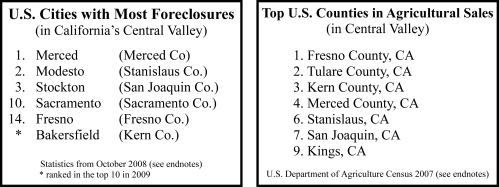

With increasing mechanisation of agriculture and the use of genetically modified crops, higher yields can be achieved with fewer workers. Farm work has always been seasonal and unstable. Currently 92 percent of agricultural workers are immigrants; this dates to the 1849 Gold Rush. Around that time Chinese workers, ‘coolies', were brought in to build the railroads. Once the transcontinental railroad was completed in 1869, many worked in mining until racism and declining yields drove them off. Some worked in the fields until the anti-Chinese pogroms, starting in the late 1870s, drove most back to the cities.11 Growers then turned to Japanese, Sikh, Filipino, Armenian, Italian, and Portuguese immigrants; later they used ‘Okie' and ‘Arkie' (native-born whites, mostly former sharecropper or tenant farmers from Oklahoma and Arkansas, as well as Missouri and Texas) Dust Bowl refugees during the Great Depression. Mexicans were brought with the Bracero Program in 1942 and today, along with Central Americans, have become the overwhelming majority.

Image: Exodus of Dust Bowl Refugees To California's Central Valley during Great Depression, circa 1939

One Big Union

Fresno was home to the successful six-month Free Speech Fight by the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW, the ‘Wobblies') in 1910-1911. Several hundred Wobblies and migrant workers came from all over the West Coast to support the right to ‘soapbox' and organise on public streets. At the time, Fresno called itself the ‘Raisin Capital of the World' and at the end of each summer 5,000 Japanese workers and another 3,000 hobos would arrive in Fresno for the grape harvest. Much like the tent cities today, workers camped out downtown and looked for work in the ‘slave market'. The Japanese were often very united and willing to strike for higher wages and better conditions. Knowing that the IWW tried to organise all workers, regardless of race, nationality, or ethnicity, the local elites were terrified that the Japanese might align themselves with the IWW. To prevent free speech there was violent harassment and mass arrests of IWW soapbox orators, often using vigilantes. In court, Wobblies used the opportunity to take up as much time as possible in political trials to agitate for class struggle. Because their free speech fight was victorious, it led to Fresno political leaders and local farm owners being more tolerant of the conservative American Federation of Labor's attempt to organise farm workers.

The IWW's next major confrontation was in 1913 in the Sacramento Valley's hop-growing region. The Durst Ranch in Wheatland advertised in newspapers throughout California for 2,700 workers, when only 1,500 were needed. This was done to create a surplus of workers to push down wages. It drew 2,800 workers of 27 ethnicities, speaking two dozen languages. It was extremely hot, there was no clean water, and there were only nine outdoor toilets. People had to sleep in the fields if they did not want to pay Durst for a tent; without clean drinking water the only alternative was paying Durst's cousin five cents for lemonade. Stores in town were forbidden from selling at the ranch, forcing people to buy supplies at Durst's own store. With no garbage removal or sanitation, many people became sick. Durst withheld 10 percent of wages until the end of the harvest, hoping the filthy conditions would drive many to leave without collecting them.

Around a hundred men had some experience with the IWW; they quickly called a meeting that focused more on the deplorable living conditions than on wages. As 2,000 people gathered to hear the Wobbly organisers speak, the meeting was broken up by the sheriff. In the ensuing riot four were killed, two workers and two in the sheriff's posse. Most workers left the Durst Ranch and scattered. A witch-hunt for the Wobblies accused of inciting the riot terrorised radicals across California. A state investigation into the squalor at the ranch led to new laws requiring improvements in living conditions for agricultural workers.

The farm worker organising drive in 1965, led by Cesar Chavez and what became the United Farm Workers (UFW), in Delano showed that after 50 years the conditions for workers in the Valley had not changed. The maintenance of a ‘reserve army of labour', using racism to keep workers divided and weak, resulted in low wages and conditions in the 1960s not much different from the ones that sparked the spontaneous revolt at Wheatland in 1913. They remain nearly the same today.

Housing Bubble in the Exurbs

Agricultural employment has always fluctuated seasonally, so the growth of housing developments in the Central Valley over the last 30 years has given workers the option of steady construction work. The housing boom, which began on the heels of the collapse of the dotcom bubble in 2001, increased the need for workers until the housing bubble itself collapsed in 2007. Along with the drop in construction jobs, drought conditions have combined with increasing mechanisation and concentration of agricultural production to throw even more people out of work. There are simply fewer farms, each significantly larger in size, that produce larger yields per acre. This process of increasing capitalist centralisation in a region that was already the first in the US to have industrial agribusiness on a mass scale continues the process of replacing people with machines, substituting ‘dead labour' for living workers.

To facilitate the production of agricultural commodities on the scale that exists today, water was also commodified through an extensive storage and transfer network that was built in two phases. Prior to the federal government's Central Valley Project in 1937, there was not enough water in the San Joaquin Valley to grow vegetables, fruit or nuts. A system of interconnected canals, dams, reservoirs and pumps was required to move water uphill from sea level in the North to an elevation of 150 metres in the arid South. The 1961 State Water Project expanded this and allowed water to be moved even further beyond the Valley, into southern California, becoming the world's largest irrigation system.

California's development has always been based on the ideology of endless growth and soil as real estate. Starting in the 1980s, laws governing water distribution were being deregulated and the bureaucracies managing water became less influenced by agribusiness and more under the control of developers. Suburban voters approved legislation allowing even more sprawling suburban development. With demand for water outstripping supply, the conditions for future man-made droughts were being created. This process, with fertile farm land being paved over and developed into new cities and suburbs, means that water once used for Valley agriculture is now used for housing. Developments as far away as Orange County in southern California, Las Vegas, Nevada, and Phoenix – more than 1,000 kilometres away in the rapidly developing Sunbelt of Arizona – were made possible by this process. This water, freed from its obligations to Valley agribusiness, was part of the fuel that fed the massive housing boom throughout the western US.

Toxic Work

The Valley was intensively cultivated after the discovery of gold in 1848; capitalism seemingly appeared out of nowhere. Yet California gold allowed the world economy to recover during the age of revolution in Europe, as well as fuelling the rapid urban industrial expansion in the US that was able to stretch across the North American continent. The San Francisco Bay Area became one of the most dynamic regions of capitalist accumulation in the late 19th century. California's further expansion was based on ‘green and black gold', agribusiness and oil.11 Starting in the early 20th century, several California counties led the US in the production of both.

This social and economic process, articulated by Marx as the move from ‘formal' to ‘real' domination of capital over labour, created highly productive agricultural sectors that took advantage of advances in transportation technology to sell products on the world market.12 Frank Norris' novel, The Octopus: A California Story, paints a vivid picture of how this proletarianisation of the agricultural labour force began in the Central Valley in the 1880s. A generation later, in his novel Grapes of Wrath, John Steinbeck describes how the Joad family completed this process of transformation from tenant farmers in Oklahoma – forced off the land as ‘Dust Bowl' refugees – to proletarians, desperately looking for work, in the Central Valley during the Great Depression. Similar conditions exist today as an army of Latino farm and ranch workers travel throughout California seeking to toil for low wages, under equally precarious conditions, with the main difference being their increased exposure to toxic chemicals.

Image: A newly finished house is demolished in California

As farms and ranches have become increasingly centralised and concentrated, they have shifted to a narrower range of more lucrative cash crops and livestock production. Between 1996 and 2006 dairy production increased by 72 percent and almond acreage by 127 percent.13 An amazing 80 percent of the world's almond crop comes from 250,000 hectares of orchards in the Central Valley. But this form of monoculture has its toxic effects: bees are required to pollinate the almond trees, but there are simply not enough in the Valley. Over 40 billion bees are brought in for the three weeks the trees are in bloom in February, some being trucked from as far away as New England and others flown from as far as Australia. En route the bees are fed what amounts to insect junk food: ‘high-fructose corn syrup and flower pollen imported from China.'14 This toxic lifestyle where bees are prostituted for money might be causing Colony Collapse Disorder; as many as 80 percent of bees have left their hives, never to return. Bees pollinate nearly two thirds of plants that end up as food, so this could prove disastrous.

As agricultural production becomes more automated and mechanised, it constantly throws people out of work. With the near complete collapse of housing construction, the official unemployment rate in the San Joaquin Valley is 15.4 percent – which counts neither the underemployed nor those who have quit looking for work. The actual rate is probably double; the highest official rate for a county is Colusa, with 26.7 percent, in the Sacramento Valley.15 The ‘Unemployment Capital of California' is Mendota, a town of just under 10,000 that is 95 percent Latino, located 50 kilometres West of Fresno. Former agricultural workers make up nearly all of the 41 percent who are jobless. Mendota claims to be the ‘Cantaloupe Capital of the World', but it is a crop that requires irrigation and the drought has prevented planting. Alcoholism runs rampant in town and as the social fabric breaks down, the only possible future jobs are at the nearby Mendota federal prison that sits only 40 percent finished due to budget problems. Another $115 million is required for its completion, so President Obama's pledge of $49.4 million in ‘stimulus' money will help it get closer. It will create 350 jobs when finished. But if social breakdown continues, Mendota residents might either find work as prison guards or end up incarcerated. Prisons are a growth industry in California, with one in six inmates serving a life sentence.

Toxic Self-Medication

Fresno tent cities are plagued with a high level of drug use, particularly methamphetamine – commonly called ‘meth' or ‘crystal meth'. Local healthcare workers have declared that the use of this addictive psychostimulant drug has reached ‘epidemic' proportions, giving Fresno the distinction of being the ‘Meth Capital of the World'. The Valley was the birthplace of the modern illicit form of this drug, originally produced and distributed by biker gangs like the Hell's Angels. The biker drug networks were broken by the police in the early 1990s, only to be replaced by Mexican drug cartels using even more rationalised systems of production and distribution. The Valley around Fresno is central to meth production not only because of the large scale operators, but also the tens of thousands of smaller producers, all of whom use the rural setting to operate clandestine labs to avoid detection.

The chemicals used to produce meth are not only highly toxic, but highly flammable. Many meth labs have exploded due to this, killing the cookers and burning down all the buildings nearby. Each kilogram of meth produced results in five to seven kilos of waste. These toxins often get dumped in remote rural areas, such as the parks and forests in the foothills enclosing the Valley.

Bakersfield & the Valley's Toxic South End

Oil was discovered in the southern part of the Valley in Kern County in 1899. Its oil fields make it one of the highest yielding counties in the US; the city of Bakersfield is called the ‘Oil Capital of California'. Refineries in the area add to the toxic mix, giving off chemicals like hydrofluoric acid. Bakersfield ranks #1 as the most polluted city in the US, based on amount of particulates; Women's Health magazine rated Bakersfield as the ‘#1 Most Unhealthy City in the U.S.' for women.

The South end of the Valley was a desert until water projects made irrigation possible. The soil contains salt and alkali from an ancient seabed; these are leached out by irrigation and the run-off mixes with agriculture chemicals, becoming wastewater. A plan was devised for a master drain down the centre of the Valley to dump this toxic water into the Delta of the San Francisco Bay, flushing it out to the Pacific Ocean. But the project was never completed because of environmental protests; San Luis Drain only went a short distance to the Kesterson National Wildlife Refuge for migratory birds. Ponds fed by the drain flooded the marshes and grasslands near Los Banos. Birds began to die in large numbers, chicks were born with grotesque birth defects, and cattle grazing nearby became sick. The cause was selenium, a naturally occurring trace element common to desert soil; it was loosened by irrigation and washed downstream by the drain project. The short-sighted solution was draining the ponds, capping them with soil, and closing the wildlife sanctuary.

Chemical-intensive farming allows for higher productivity from fewer acres, but agribusiness intensifies the process of soil depletion and will eventually result in salinisation, desertification, and outright toxic contamination. The accumulation process is blind to the toxic residue from the use of insecticides, fungicides, herbicides, and petroleum based fertiliser. The drain water of the massive irrigation project pollutes ground water with all these toxins, but it also leaches toxic metals, like lead, and salts containing selenium out of the soil. The results are environmental diseases because these chemicals contain carcinogens that cause cancer, teratogens that cause birth defects, and mutagens that cause genetic changes. In 1988 the UFW demanded that five toxic pesticides used by grape growers – dinoseb, methyl bromide, parathion, phosdrin, and captan – be banned.

Chemicals used in pesticides and for other agricultural purposes are rarely tested properly, and almost never are they observed in the combinations in which they enter the human body. A 1996 federal study found that in combination certain chemicals accelerated the body's production of oestrogen, a hormone linked with causing breast cancer and deforming male sex organs. Men working in pesticide plants near Stockton were sterilised by exposure to these.16

Toxic Housing

The housing boom was fuelled by the creation of collateralised debt obligations, pushed with the aggressive marketing of subprime and other risky mortgages, which became ‘toxic assets' when the bubble burst and the market rapidly filled up with foreclosed homes and collapsing prices. A toxic asset is an abstract concept, mostly affecting investors exposed to them, but the housing boom created hundreds of thousands of homes that are literally toxic. The confluence of the national housing boom and the rebuilding of New Orleans and other areas of the South, in the aftermath of Hurricanes Katrina and Rita in 2005, created a massive demand for drywall.17 So builders imported 250 million kilos of drywall from China, some of which ended up in new homes in the Central Valley. The Chinese toxic drywall gives off carbon disulfide and carbonyl sulfide, causing corrosion of copper pipes, electrical wiring and appliances. People have suffered nosebleeds, rashes, and children have been afflicted with ear and upper respiratory infections.18 This, sadly, is the perfect metaphor for the economic conditions, shamelessly caused by capitalist centralisation, which the working class in the US must live and toil under: toxic!

An Image of Our Own Future?

Capitalist centralisation in California has continued unabated from the time Marx noticed it, even gaining speed, leaving in its wake a toxic wasteland of contaminated ecosystems as well as toxic lives where capitalism contaminates every aspect of human social relations it touches. In his novel The Octopus, Frank Norris calls this ‘the true California spirit', an attitude he dates to the Gold Rush that never died:

They had no love for their land. They were not attached to the soil, they worked their ranches as a quarter of a century before they had worked their mines. To husband the resources of their marvellous San Joaquin, they considered niggardly, petty, Hebraic. To get all there was out of the land, to squeeze it dry, to exhaust it, seemed their policy. When, at last, the land worn out, would refuse to yield, they would invest their money in something else; by then, they would all have made fortunes. They did not care. ‘After us the deluge'.19

Marx suggested we observe ‘phenomena where they occur in their most typical form' and in his day that meant ‘production and exchange' and the conditions of ‘industrial and agricultural labourers' in England (so as to refute those who say ‘things are not nearly so bad' where they live). The toxic conditions in California's Central Valley – affecting human lives as well as the health of the entire ecosystem – demonstrate how the crisis of over-accumulation of capital leads, if allowed to take its course unopposed, to the destitution of the working class and the despoilation of the planet. As Marx warned,

The country that is more developed industrially only shows, to the less developed, the image of its own future.

De te fabula narratur!

[‘The tale is told of you.' - Horace]20

Originally published at www.metamute.org

- 11 Frequency of foreclosures from Center for Responsible Lending, ‘Mortgage Lending Overview', http://www.responsiblelending.org/mortgage-lending/ ; number of empty homes at the end of 2008 from Kathleen M. Howley, ‘Record 19 Million Homes Stood vacant in 2008', 3 February 2009, http://www.bloomberg.com/apps/newspid=20601087&refer=home&sid=aKufqJK9j1cY ; homeless statistics from National Law Center on Homelessness and Poverty, ‘2007 Annual Report'; http://www.nlchp.org/content/pubs/2007_Annual_Report2.pdf p.5.

- 2See, ‘Housing Market Collapses, Literally', http://www.boingboing.net/2009/05/11/housing-market-colla.html; ‘Exurban sprawl' is defined as low-density rural residential development causing land-use changes in areas beyond the urban and suburban fringe, creating extensive and widespread negative ecological effects to ‘protected' lands meant to conserve natural resources and biodiversity. It also includes commercial strip development alongside roads outside of cities and suburbs. For further elaboration, see David M. Theobald, ‘Landscape Patterns of Exurban Growth in the USA from 1980 to 2020', Ecology and Society, Vol. 10(1), http://www.ecologyandsociety.org/vol10/iss1/art32/

- 3Jennifer Levitz, ‘Cities Tolerate Homeless Camps', Wall Street Journal, 11 August 2009, http://online.wsj.com/article/SB124994409537920819.html

- 4See our account of meeting the ‘Governator' and mayor at the tent city: http://flyingpicket.org/?q=node/46 , as well as our return visit to help build a latrine in solidarity: http://flyingpicket.org/?q=node/49

- 5Gray Brechin, Farewell, Promised Land: Waking from the California Dream, Berkeley: University of California Press, 1999, p.77.

- 6For foreclosure rates as of October 2008, http://realestate.yahoo.com/Foreclosures; Bakersfield 2009 ranking with US cities for foreclosures from ‘Sun Belt Dominates 1h09 Foreclosure Rankings', Florida Real Estate Journal, 31 July 2009, http://www.frej.net/news/news/2009-07-31/sun-belt-dominates-1h09-foreclosure-rankings ; top 5 US counties in agricultural sales 2007 USDA Census from Economic Research Centre, ‘Data Sets', http://www.ers.usda.gov/StateFacts/US.htm

- 7‘Central Valley Town Owns Nation's Dirtiest Air', BNET, http://findarticles.com/p/articles/mi_qn4176/is_20070810/ai_n19478485/

- 8As of March 2009, according to Belinda Jackson, ‘Four US Cities With Highest Unemployment Rate', Money Blog, http://personalmoneystore.com/moneyblog/2009/04/30/cities-highest-unemployment-rate/

- 9Barbara Anderson, ‘Fresno is State's Asthma Capital', Fresno Bee, http://www.fresnobee.com/868/story/263218.html

- 10Jesse McKinlet ‘Cities Deal With a Surge in Shantytowns', New York Times, 25 March 2009, http://www.nytimes.com/2009/03/26/us/26tents.html

- 11Edward W. Soja, Postmodern Geographies: The Reassertion of Space in Critical Social Theory. London: Verso, 1990, p.191.

- 12A coherent definition is taken from the Internationalist Perspectives website: ‘This view of the transition from the formal to the real domination of capital, then, rests not just on Marx's distinction between the extraction of absolute surplus-value and the extraction of relative surplus-value, but on its expansion from the economy to society as a totality; from the process of production to the processes of reproduction – the reproduction of the capitalist social relations, the core of which is the value form. This reproduction, therefore, involves demography, technology, science, the modes of subjectivation of the human being, the political and cultural domains, as well as the economic, and the vast realm of ideology, understood not simply as false consciousness, illusion, or mystification, but rather as consciousness, beliefs, actions endowed with a material existence, and inextricably linked to the no less material existence of a determinate mode of subjectivation of the human beings, and the classes, that inhabit that civilisation. Thus, in contrast to the formal domination of capital over society, in which only the immediate process of production is subject to the capitalist law of value, and the other domains of social existence still retain a considerable degree of autonomy from it, the real domination of capital over society entails the penetration of the law of value into every segment of social existence. Thus, from its original locus at the point of production, the law of value has systematically spread its tentacles to incorporate not just the actual production of commodities, but their circulation and consumption too. Moreover, the law of value progresses and comes to preside over the spheres of the political and ideological, including science and technology.' See, ‘How Capital's Progress Became Society's Regression', http://internationalist-perspective.org/IP/ip-archive/ip_42_capital.html

- 13Eberhardt School of Business, Business Forecasting Centre, ‘Unemployment in the San Joaquim Valley in 2009: Fish or Foreclosure?', 11 August 2009, http://forecast.pacific.edu/articles/PacificBFC_Fish%20or%20Foreclosure.pdf

- 14Michael Pollan, ‘Our Decrepit Food Factories', 16 December, 2007, http://www.michaelpollan.com/article.php?id=91

- 15‘California's Jobless Rate Hits 11.6 Percent', Central Valley Business Times, 17 July 2009, http://www.centralvalleybusinesstimes.com/stories/001/?ID=12565

- 16Gray Brechin, op. cit., p.168.

- 17‘Drywall is the term used for a common method of constructing interior walls and ceilings using panels made of gypsum plaster pressed between two thick sheets of paper, then kiln dried.' From Wikipedia, http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Drywall

- 18M.P. McQueen, ‘The Prisoners of Drywall', Wall Street Journal, 6 August 2009, http://online.wsj.com/article/SB10001424052970203674704574332264031026476.html

- 19Frank Norris, The Octopus: A Story of California, New York: Penguin Books, 1986 (first published 1901), p.298.

- 20Karl Marx, Capital: A Critique of Political Economy, Vol. I, New York: Vintage Books, 1976. pp.90-91.

Comments