In the second year of the Great Leap Forward famine – in which perhaps 30 million died, anarchist Herbert Read visited China on an official delegation. Read’s acceptance of a knighthood for his literary achievements had already discredited him amongst many anarchists. But, at the time of his visit in 1959, he was still the most prominent anarchist in Britain and his published writings had considerable influence on, amongst others, Murray Bookchin.†

Read’s ‘Letters from China’ show how easy it is for a radical intellectual to get it completely wrong. The nearest comparable episode was in 1967 when Noam Chomsky used phrases like ‘mutual aid’, ‘popular control’ and ‘nonviolence’ while referring to Mao’s collectivization policies. (Later, in 1977-79, Chomsky was also reluctant to acknowledge the full horror of Pol Pot’s version of these policies. See ‘Chomsky on Cambodia’ and here and here.)

These extracts are a timely reminder to be sceptical of any account that claims that the new revolutionary society is being constructed outside of a global working class revolution:

EXTRACTS FROM HERBERT READ’S ‘LETTERS FROM CHINA, 1959’

The afternoon was devoted to the Forbidden City [in Peking]. … Everywhere the people are wandering around, free & happy. Delightful children, amused to see foreigners. There is an extraordinary air of happy-go-lucky contentment everywhere, but everyone is working (there is no unemployment, but a shortage of workers). …

[The Chinese] are extremely moral, in fact puritanical. Crime has, apart from occasional 'crimes of passion', practically disappeared. Each street has a committee which settles all disputes, and there are women’s associations that look after the morals of the inhabitants. Theft, which used to be frequent, is now almost unknown. … Food is plentiful & cheap. …

To-day began with the most interesting event so far – a visit to an agricultural commune. These communes have come into existence spontaneously during the past 12 months (previously there were various types of collectives, where work & implements were only partly shared). There are now 24,000 of them, covering practically the whole country & having 450 million members. It is my idea of anarchism come into being, in every detail & practice. …

The commune is divided into five brigades – we were in the Peace Bridge brigade & had then to listen to all the statistics for the brigade. Then a description of how it all works, most interesting – but the most important fact is that these communes are autonomous, which makes them anarchist from my point of view; and they are successful – Production has gone up by leaps & bounds, earnings of workers have doubled, schools & clinics have been provided (33 doctors in this one commune – ten years ago there was none). Many other improvements. …

But everywhere there was pride in their achievements & a feeling that the wicked landlords had gone forever. I forgot to ask what had happened to their wicked landlord – no doubt he was in charge of one of the five piggeries. All this sound dull, but I found it fascinating – a dream come true. …

I wish you could see what is going on here socially & economically – it is the biggest & most successful revolution in history, & very inspiring. We spent this morning at Peking University & there too (in education) they have there own completely convincing methods. …

I remarked to the interpreter that I had not seen a policeman, & he answered as I expected, that they were not needed since the Liberation.

There is still a lot of poverty, though the average income [increased] fourfold since the liberation – from £15 a year in 1949 to £65 now – but now they also get free food (for which they pay 18/- a month). Again much evidence of the moral revolution – as the [commune] Chairman said, in the past much fighting, quarrelling, selfishness, now ease of mind, poetry & song. …

All these communes are virtually self-supporting – the only things they need to get from outside are heavy machinery like tractors & perhaps coal & minerals like cobalt. It is the complete decentralization of industry advocated by Kropotkin in ‘Fields, Factories & Workshops’. …

I warn some of them [about the technological destruction of natural beauty], but they smile & say it will be different with us – our workers will be educated, they will want beauty & leisure & we shall not repeat the mistakes of the capitalist world. You get the same answers everywhere, & it is not indoctrination, but a faith that moves mountains. …

There are slogans & posters everywhere, and party literature in every hotel lounge: but like the professor this afternoon, however firm their faith, they are willing to discuss it in a free & friendly manner. …

(From A Tribute to Herbert Read, 1893-1968, p44-49, emphases added.)

Here are some other accounts inspired by visits to various ‘socialist’ regimes:

Victor Serge, Year One of the Russian Revolution

– in which Serge, a former anarchist exiled in Russia, defends the Bolshevik Party, saying the Party ‘must know how to stand firm sometimes against the masses’ and ‘to bring dissent to obey’.

Sidney and Beatrice Webb, The Truth about Soviet Russia

– This pamphlet summarises the book, Soviet Communism: A New Civilisation, which was inspired by a visit to the USSR during the devastating Ukrainian famine. In the pamphlet, these influential intellectuals overlook the famine while claiming that ‘Stalin is not a dictator’ and that the USSR is ‘not only a political but an industrial democracy’.

Simone De Beauvoir, The Long March

– in which De Beauvoir claims of Mao that ‘the power he exercises is no more dictatorial than, for example, Roosevelt’s was.’ De Beauvoir visited China with Jean Paul Sartre, who, after his earlier visit to the USSR, had concluded that ‘the Soviet citizen has, in my opinion, complete freedom of criticism.’

Paul M.Sweezy, Cuba: Anatomy of a Revolution

– in which Sweezy says that there is no sort of ‘totalitarian dictatorship’ or dogmatic ‘line or ideology’ in Cuba.

Joan Robinson, ‘The Korean Miracle’

– in which the influential Keynesian economist says that Kim Il Sung ‘seems to function as a messiah rather than a dictator.’

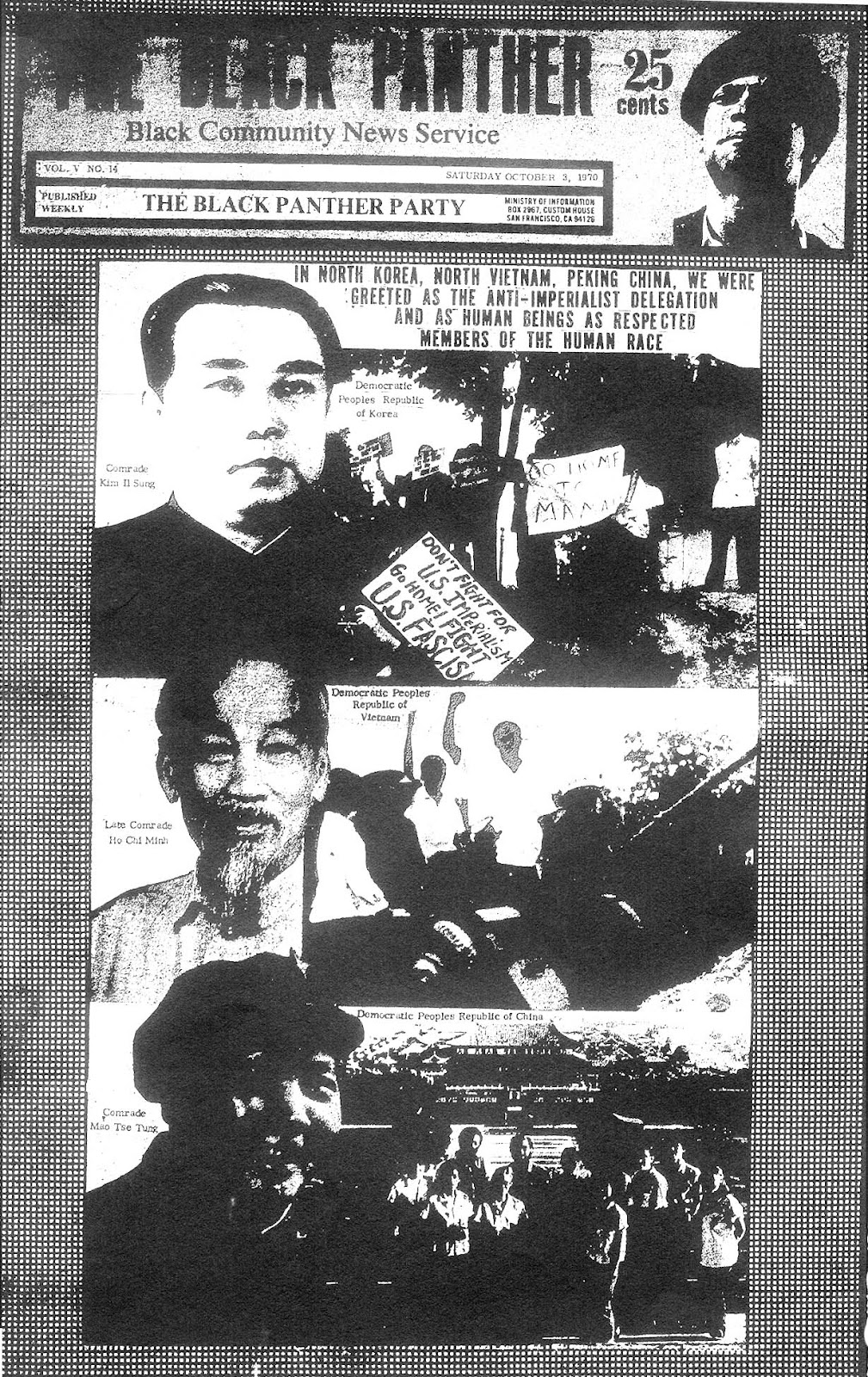

‘Statement from Black Panther Delegates to North Korea’

– in which North Korea is described as a ‘paradise’.

Noam Chomsky, ‘In North Vietnam’

– in which Chomsky says ‘there appears to be high degree of democratic participation at the village and regional levels.’

Dan Burstein, ‘Exclusive Eyewitness Report from Kampuchea’

– in which Burstein says he saw ‘not a single sign of coercion’ in Pol Pot’s Cambodia. In another article he wrote that a ‘very broad democracy exists in the cooperatives’.

Image of Khmer Rouge fighters from this film

Michel Foucault, ‘What are the Iranians Dreaming about?’

– in which Foucault says that ‘by Islamic government, nobody in Iran means a political regime in which the clerics would have a role of supervision or control.’ Foucault also seemed to believe that under such an Islamic government, ‘between men and women there will not be inequality with respect to rights.’

Alex Mitchell, Come the Revolution

– This book includes an account of several Workers’ Revolutionary Party trips to Libya to obtain funding from Gaddafi’s ‘revolutionary’ regime.

Tariq Ali, Revolution from Above

– in which Ali recounts how he tried to convince Piotr Suida, a survivor of the 1962 Novocherkassk massacre, to join the Russian Communist Party. Ali dedicated his book to the Moscow Party leader, Boris Yeltsin, in the hope that the Party leadership would revive Soviet socialism.

Chomsky, Albert and Chavez

Michael Albert, ‘Venezuela’s Path’

– in which Chomsky’s colleague, Michael Albert, praises Hugo Chavez’s Bolivarian revolution for a ‘vision that outstrips what any other revolutionary project since the Spanish anarchists has held forth.’ In 1980, Albert was similarly naive about China’s Maoists, claiming that they may have genuinely wanted ‘greater worker and peasant power’. (For different views on Chavez, see: 'The Revolution Delayed' and ‘Dead Left’.)

David Graeber, ‘No. This is a Genuine Revolution’

– in which Graeber explains that the Rojavan ‘security forces are answerable to bottom-up structures’ and that they intend to ‘ultimately … eliminate police’. See also his ‘I Appreciate and Agree with Ocalan’ interview.

Janet Biehl, ‘Impressions of Rojava: a Report from the Revolution’

– in which Biehl says that ‘women are to this revolution what the proletariat was to Marxist-Leninist revolutions of the past century’ and that although ‘images of Abdullah Ocalan are everywhere’, there is nothing ‘Orwellian’ about this. (For a variety of views on Rojava, see the ‘Rojava Revolution Reading Guide’.)

It may seem unfair to include anti-Stalinists like Chomsky and Graeber in the same list as those who had real illusions in Stalinism and Maoism. But critical thinking is essential for working out how to make a revolution that does succeed. It is therefore important to show how a neglect of critical thinking can affect any of us.

(† D.Goodway, Anarchist Seeds beneath the Snow)

Comments

Quote: Several points: 1.

- here

In this "Anti-War"

In this "Anti-War" publication, he/she/they provided some interesting links to texts to read about "useful idiots" who praised some last decades impostures: China, Vietnam, Kampuchea, North Korea, etc. If readers didn't make the effort to click on each of those links, here I publish one of these texts. It's the interview of Dan Burstein about its visit to Kampuchea in 1978:

Rojava... (Whoops) Kampuchea Takes the Socialist Road

Let's just emphasize among all the bullshit of this beautiful fairy tale this quote about the system of cooperatives:

https://www.marxists.org/history/erol/ncm-5/burstein-class-struggle.htm

I know that "comparisons are odious" (Frenchies say "comparaison n'est pas raison", litterally "comparison is not reason") but it's somehow interesting to juxtapose this quote with some praising the same cooperative system in Rojava and you will see that there is the same uncritical mood to believe and praise any "radical" reform that sounds like, that smells like, that looks like revolution but that is nothing else than a watered-down version (Frenchies would say a Canada Dry version):

http://www.biehlonbookchin.com/rojavas-threefold-economy/

http://libcom.org/library/mountain-river-has-many-bends

The link for Chomsky's quote

The link for Chomsky's quote regarding "mutual aid" and "popular control" in Mao's collectivisation goes to an article for NY Books where he's discussing a village in Thanh Hoa, writing:

That is, a state sanctioned entity also carries benefits which arrive through the free arrangements of individual members. Possibly the least contentious political statement I've seen made. To claim that Vietnamese collectives were the result of Maoist policy is to embrace the most reactionary stance on history.

Popular control is referred to in the following passage:

High degree of participation?

Perhaps that's an unconscionable statement.

A couple of point: Quote: in

A couple of point:

Yes, a former anarchist who, when he wrote the work in question, had been a Leninist for nearly a decade. Unsurprisingly, a Bolshevik is defending the Bolshevik party...

(for more on Serge, see my Victor Serge: The Worst of the Anarchists)

As for Chomsky:

Talk about selective quoting. Chomsky actually states:

he also states:

So he clearly indicates that the regime had "centralisation of control" with "party direction", so hardly saying what is being claimed he said. In other words, he is saying there are good elements and bad ones within the regime.

As for the "mutual aid" comment, he is simply stating that co-operation (joint effort) has advantages. He also noted that this was the case in the old regime as well:

Presumably him noting these facts means that he is a supporter of feudalism?

So less of the selective quoting -- I can only assume the link was provided on the assumption that no one would check...