Against a kind of activist-y, spectacular politics, Marianne Garneau argues that US students and workers can learn from the Quebec model how to organize our power as a class. Quebec students have kept their tuition low because they’ve historically had a vibrant, militant student movement, one that is willing to strike and directly disrupt, and not wait for the leadership of the business unions. The organizing model is to create directly democratic bodies—department-by-department assemblies—that know how to leverage our power to fuck up the business of the people who are screwing us over, whether they’re our educators or our employers.

CW: Could you say a little about how you became involved in radical organizing, particularly around universities?

Marianne: I first became political by participating in the punk scene where I grew up, and I started university in ’97. Of course, just a couple years after that the anti-globalization movement took off, and so, while I was doing my BA my friends were going to Seattle and to Quebec to participate in the anti-globalization protests. I didn’t go to those cities but I was obviously involved in those politics and in the local manifestation of that movement; we’d have marches and stuff [where I lived too]. But I wouldn’t say I was doing anything terribly significant at the level of organizing students, although I did know people who were. So, then I went and did my master’s degree elsewhere in Canada, and then I came to New York in 2006. Throughout that time I was involved with the IWW [Industrial Workers of the World], although not terribly active. I did do some workplace organizing, but not through the IWW. And I did various political, sort of activist-y type stuff. So, I got to New York in ’06; came here to do my PhD in philosophy, and I decided to lay low while I was here—not being a citizen, being here on a visa, and so not having all the protections you would have to operate politically as you do when you are citizen. I was still interested in stuff but I wasn’t really actively doing much.

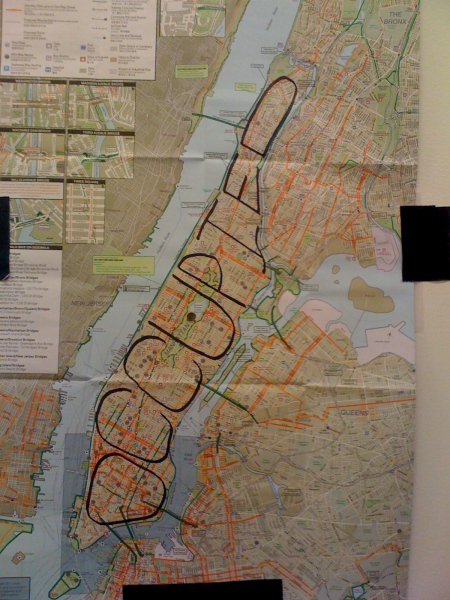

And then Occupy started. The Zuccotti encampment was literally two blocks away from my house, and so I was just thrust into the middle of it, and also very much interested in it, actively. It re-animated that whole political side of me that had been latent for a few years, and I couldn’t help but get involved. Shortly after Occupy started, students in New York started meeting—university students across different universities in New York: from the New School (where I’m at), from NYU, from the various CUNY system, from Juilliard, I think a couple from Columbia—and we started meeting weekly. Basically, the issues that started to come out organically had to do with things like student debt, which is really atrocious in the United States, tuition—because tuition was going to be raised at CUNY by something like 30% over 7 years and they wanted to resist that; as a bastion of public education, it’s supposed to be accessible. CUNY used to have open enrollment, and I think it used to have zero tuition. So, students started meeting in New York. Last November, as part of that, there was an occupation at the New School, which I got heavily involved in. Through this process, I came back to the Wobblies [the IWW] and have started doing more concrete organizing that kind of overlaps the student organizing category and the labor organizing category.

Occupied Manhattan – A picture from inside the New School student occupation in November 2011 (it started on the 17th, which was the big day of action for education, and ended a week later). It involved post-secondary students from all across New York, and took place in a New School student study center at 90 5th avenue. (pic from Marianne Garneau)

CW: Could you say more about your IWW organizing and how you’re connecting that with the Occupy organizing?

Marianne: Sure. So, the IWW has a branch here that probably has over 100 members, if you’re going to be more inclusive about it. But in any given month, we probably collect dues from between 50 and 70. There are a couple bigger campaigns in New York, like the Focus on the Food Chain campaign. It’s a good, active branch.

When Occupy started, a number of different working groups started, and some of them had a labor focus. One of them was called Occupy Your Workplace. Some Wobblies have been involved in that, including myself since a couple of months ago. Another fellow worker has been involved with that since the beginning. One of the things we’ve done is run organizer trainings through the IWW, but reaching out to people through the Occupy Your Workplace working group, and that has ended up getting some new members on board in the Wobblies.

That’s a kind of structural overlap that’s taking place. But I could also describe the overlap for myself. The thing about being involved with the IWW is it gives you a good clear organizing focus and skill-set and orientation. So, when the student stuff kicked off in New York around Occupy, in September, October, and November, and through the winter, it had a very activist-y focus. And that has its limitations. You can sort of be visible and spectacular and pull stunts and have days of action and marches and whatever, the kinds of stuff they were organizing. For example, we were protesting outside of CUNY when they were voting on whether to raise tuition, which of course they did. Actually, that’s an amazing story too. There was a day that the board of governors were meeting, they cancelled classes and locked the building down and had the meeting, which actually by law is required to be a public meeting because they are a public university. So, we all stood outside and protested.

CUNY protest against tuition hikes (pic via NY Times)

At the time it felt like that was the only thing we could do. But, then you look at something like what’s going in Montreal right now, where they organize themselves into assemblies, university by university, faculty by faculty, department by department. That’s where that strike mandate came from, from that real democratic procedure. In New York it’s been more on the order of activist-y, what I like to call spectacular politics, which is a technical academic term for this stuff that you do that’s very visible but not necessarily organized at the real locus of power. Now, I’m moving more to this Montreal model of organizing.

So, right now I’m working on this campaign at the New School to organize student workers, and there’s a real significance of that kind of campaign at the New School because the New School is extremely expensive, located in an extremely expensive city, and they offer probably worse funding to their students, especially at the graduate level, than any other post-secondary institution in the country. They not only don’t offer funding packages, supporting funding packages like stipends that you could live off of, but they charge you tuition as a graduate student—and tuition is $25-30,000 a year, and they’ll discount it for you as a graduate student, but you’re still paying out of pocket to be there. Whereas, most universities are paying you to be a grad student, they’re investing in you. As a result, pretty much every student at the New School ends up working at the New School in some part-time temp-y type job, and people get federal work-study. I don’t, as an international student, but a lot of people get federal work-study as part of their funding package, which you work out. You get a reward of, like, $2000, and you work for it as a job. The thing is that the New School then hires these students at a rate of $9 or $10 an hour, so they’re prioritizing exploiting the labor of their own students over their students receiving funding so that they can be students, so that they can have the time and opportunity to study and develop themselves as students. Besides the work-study, there are a lot of students who work on campus to get employment, again, strictly out of financial necessity. And, the New School, the way that they pay us, the way that they treat us, the way that they’ll jerk people around—they’ll reduce their hours to like one hour a week or they’ll award them money and take it away or give them jobs and take them away or pay really poorly, and none of this has any benefits either. They’re treating us as though we’re like teenagers living at home with mom and dad who want some pocket money for beer. The way they treat us as laborers is sort of with that kind of contempt. And yet they know that’s not the case at all, they absolutely know that their students are trying to support themselves in very expensive New York City.

So, we’ve started meeting. This is where a more Wobbly orientation comes from. We started building a committee, reaching out to the student workers on campus, definitely within the parameters of ‘no management.’ We haven’t been involving part-time salaried employees either, not that we have an antagonistic relationship with them. But, we’re gathering and building a committee of student-workers. We’ve met a number of times so far, just kind of setting ourselves up in terms of having an email list and people’s contact information and identifying offices of where to find student-workers on campus. We’re kind of completely diffused in this school: there will be two students working in one office, and two students in another, and three in another, and we’re all in different buildings. We don’t have a typical campus either: we’re all spread out. To me, that just presents an interesting challenge as to how we’re going to organize. We kind of also by the same token have tentacles all throughout the organization, which, if you can get them to act at the same time, can have a really dramatic effect if you’re trying to pull some kind of direct action in the workplace.

So, that’s how the Wobbly thing has mostly influenced me in the student organizing that I’ve been doing: taking it in that direction of, not having some elite crack group of activist-oid students over here meeting (and I’ve been a part of that kind of thing), but having something that is based on everybody’s participation who is similarly positioned.

CW: How are you doing your campaign? Are you taking an explicitly IWW approach? Have you defined the group as Wobblies, or is it an independent thing?

Marianne: It is an independent thing. We’re not organizing under the auspices of the IWW. This campaign kind of had two starts. One was back in the spring. A couple of students met a couple of times, and we were starting to just identify this as something to organize around, but it never really got off the ground, because as students you just end up being incredibly busy and bogged down between the month of March and the end of the semester, and it didn’t have enough momentum or enough membership to keep going. So, it sort of got re-animated this summer. One of the things we did was to have this IWW organizer training. It brought in a bunch of Wobs who hadn’t done the organizer training—I actually hadn’t myself. It brought in people from Occupy Your Workplace, and I invited everyone from our campaign to participate in it. There ended up only being two people out of eight who made it.

The IWW model is the model that we’re pursuing. The good thing is that there have been people on the committee—by ‘committee’ I just mean people that are student-workers that have signed onto this campaign, share their contact information, intend to come to meetings, and have it explicitly stated that they are on board. So, there was one member on the committee who was like, ‘hey, why don’t we just do this through like, the UAW, in particular, because they organized adjuncts at the New School about five years ago?’ To make a short story long, when this student-worker organizing campaign had that first kick-off in the spring, there was one person who was coming to meetings who was, sort of, really insisting on meeting with some business union reps, particularly from the UAW. So, I conceded and I sat down and had a meeting with this woman who was involved in the campaign to organize adjuncts at the New School. She was a perfectly nice person, and she gave me a couple of beginner organizer type handouts. It was like the AEIOU stuff we talk about in our IWW organizer trainings. It was all really innocuous, good stuff. At the same time, she wasn’t terribly interested in our campaign yet, because at the time we were thinking more along the lines of organizing academically employed students—so, teaching assistants and research assistants and that kind of thing. She wasn’t terribly interested in our campaign yet. She certainly wasn’t trying to hijack it or anything, because she knew that we were at zero; we just hadn’t done any work yet. She even sort of said something like, ‘look, if the UAW were to get involved, they would only get involved once you guys had already built some momentum on the ground.’ So, they could parachute in later and start doing card check and stuff like that.

So, when this student-worker organizing campaign kicked off in the summer it had the focus of organizing work-study, and the really casual, clerical, hourly wage-slave type student-workers. Again, somebody on the campaign—somebody different this time—was like, ‘well we should do this through the UAW. We should do this because they’re already on campus. Or we should do it through the Teamsters. Let’s reach out to a business union to help us with this.’ Fortunately, there was a sort of ready-made response to shut that down, which is that, I don’t think that federal work-study students are even legally allowed to organize, but they’re definitely legally prohibited from striking because you can’t strike the taxpayer. So, it’s built into our campaign, and into what it is that we’re trying to organize and do, that we can’t go that route. And, the same kind of suggestion comes up in another form, where people say, ‘well, how about we reach out to our shitty student union?’ It’s called the University Senate. The answer is because that’s not the kind of mandate they have either. Those guys have never done shit about this cause, they don’t talk about it, they’re not interested, and they don’t have that kind of mandate. And they’re organized in such a way that they receive—basically the university collects five or fifteen dollars from every student every semester, it’s like dues check-off, and gives it to this organization, and they just don’t do shit. They’re just not interested in that kind of thing. And they’re not going to take a position against the administration, which is who collects and hands them their money. It’s almost the same sort of structural issue that you have with a business union.

CW: Based on my experiences with business unions, I’m wondering whether or not you’re considering going with the IWW or an independent thing, and why or why not?

Marianne: I’ve been thinking more and more… What we’ve been doing instead is just an unaffiliated organizing campaign. In the day and age of Occupy and that kind of thing, I think that there’s more of a possibility of doing things like that. And people are less confused about the idea of there not being a particular nameable umbrella organization under whose auspices you are organizing or with which you are affiliated, because with Occupy, there’s no political party, there’s no trade union, there’s no particular affiliation; it’s just Occupy, and you just do stuff, and you do it via direct action. So, I think that that precedent means that when we get in a room and have a meeting with student-workers, they’re not waiting for the particular card carrying organization to show up. They understand what it is to organize on the basis of solidarity and direct action. That’s the IWW bent that we have anyway; that’s the kind of campaign this is going to be. It’s gonna be built out of a committee of workers on the floor, and we’re going to run things on the basis of direct collective action and solidarity unionism.

But, just in the last couple weeks, I’ve been thinking about how we do need something to make this concrete. You know how difficult it is to get people out to a meeting, and to convince them that what you’re starting is something actually real, and it’s solid, as opposed to just an idea of, ‘hey, working here sucks, if only it were better.’ And I feel as though it might actually be important to do this instead with the Wobs. To be extremely concrete about it, there’s something to be said of having pins and cards and a name. It’s that kind of thing that makes things real in people’s minds.

CW: Is your student-worker organizing there at the New School the only Wobbly-type education organizing in New York City or is there other education worker organizing happening?

Marianne: There’s a lot going on in New York, and, unfortunately, most of it is not happening along IWW lines, broadly construed. So, for a long time people were saying Occupy is dead, Occupy is in hibernation, and it wasn’t true—but now it’s actually true. There are still working groups and working groups still meet, and there’s still stuff going on leading up to the summer and leading up to September 17th, which will be the one year anniversary. But, the general assembly doesn’t meet anymore, which as far as I can tell is fine because it wasn’t a very effective body in the first place. But, Occupy really was going on through the whole winter and through the spring. When it was still hot, one of the things that it was doing: it had something called Occupy the DOE (which is the Department of Education), because Bloomberg had created this thing called the PEP (the Panel on Education Policy) and it was a completely disingenuous body of non-native bureaucrat fuckheads, who would look at public schools in the city and their performance and vote on whether or not to close them. I think they looked at 33 public high schools and voted to close, like, 32 of them. It was a clear powerplay on the part of the forces of capital to replace public institutions with private ones, because they then open up charter schools. I actually have a Wobbly friend who organizes teachers at charter schools (not under the auspices of the Wobs but with the AFT or UFT). So, Occupy would show up to these PEP meetings—and actually, mostly it wasn’t Occupy; it was the neighborhood parents, students, and concerned citizens at large. I don’t know if they were being partly organized by the business unions involved in the schools. So, there’d be big, big rallies outside these PEP meetings. Just to give you a picture: there was one meeting where the panel had six members, they were all sitting around a table with microphones, and they had those industrial headphones—noise-canceling headphones that dudes on the airport tarmac wear—and were just plugged into each others’ microphones. That’s how loud the room was, because the meeting was open to the public, and that’s how loud the screaming, yelling, and whistling was, on the part of hundreds and hundreds of people who were packed into there. You couldn’t hear anything but angry protest. So, there was serious public mobilization, perhaps organized a bit too.

So, that was one thing that was going on in the area of education. But, again, with the model of: show up and protest outside or inside, and be completely excluded, and they decide against your interests anyway. Another area of education organizing was a campaign five years ago organizing adjuncts at the New School. I know of campaigns elsewhere in the United States: there’s one in Chicago, of organizing adjuncts. At CUNY, the student adjuncts and research assistants are already organized, and they’re organized into the same union as the tenured faculty and everybody else. But, it’s the typical worst-case scenario of being organized by a business union. They pay their dues, they get their shitty contract, they keep their head down, they keep working. No actual real militant organization of the class.

I hate to be negative, but the positive thing to say, I guess, is that there’s been a lot of different mobilizations in New York around educational issues, like, big stuff regarding student debt coming out of Occupy. But, it takes extraordinarily unsatisfying forms. The biggest thing that’s happening now with New York City university students that are still meeting across New York City is that they’re creating this Free University. They had one on May 1st in Madison Square Park, and I went to it and it was better than I thought it was going to be. It was kind of awesome. Regularly scheduled classes were taken to the park on a completely voluntary basis by professors and students. They just relocated class that day to the park. Other things that were going on were spontaneous lectures, including well-established academics—people talking about the political moment. It was an inspiring place to walk around.

But, then, they took that model and now they’re going to kind of beat it to death. They’re going to organize an entire Free University, and it’s like, guys, this doesn’t fucking do anything: it doesn’t do anything about tuition, it doesn’t do anything about debt, or about the massive inequities that exist in the education system in the first place.

Actually, I’ll give you an even better example of this. So, Occupy Wall Street started on September 17th. October 17th was a big day of action: the one-month anniversary. November 17th was a big day of action. There was a protest, a march, I think it was on September 30th, the day that 700 people got arrested on the Brooklyn Bridge. Immediately, a group of us kind of saw each other on that march: professors and students at the New School. We started emailing each other. We had a meeting on Monday or Tuesday, and threw up some hastily printed off fliers around campus, inviting students to walk out on October 5th, five days later. And, the school actually walked out. Professors canceled classes, students streamed out of classes. There was actually a walkout at the New School. For the ostensibly radical reputation that we have, it was fucking incredible, the fact that this happened. I’ve been there for six years, nothing like that had ever happened. I would never have predicted something like that would have happened. We didn’t even organize it. There was no time to organize something like that in five days. It just happened spontaneously.

OWS – November 17th ‘Day of Action’ – (pic via Time)

Same thing happened on November 17th: high school students, university students, everybody streamed out. I was teaching as an adjunct at the time, at Juilliard, and I didn’t make my students walk out, because that’s not the point of a day like that. But I had another student come in and disrupt my class and invite my students to walk out, and they did, and I walked out with them. We came down to Union Square where the big gathering was. I was also on the inside of organizing the occupation at the New School. So, we had a big gathering at Union Square and the New School is a block away. So, as the march started, I started handing out leaflets, telling people, ‘come join the occupation right here in this building.’ We had our occupation. That was just a massive, massive day: massive mobilization.

New School Occupation – Nov. 17th, 2011 – Read the Inaugural Statement here

The occupation breaks up a week later—I can talk about that; it’s a long story. Then, what do students do? We continue meeting citywide, university students, in December. And they start planning for a fucking day of action on March 1st, another big march. It’s this bad mentality of a) giving over to politics of spectacle rather than real organizing of our power as a class, and b) thinking like, ‘that was cool and fun, that happened once, let’s just keep doing that and doing it again.’ It’s like, look, all that was fine, but it wasn’t a really powerful thing. Then, students of New York threw their weight for two and a half months of organizing towards a big day of action for education on March 1st [2012]. The call first came out of California and we echoed it in New York. We thought it would be a natural thing. We were telling as many people as possible. We were organizing the crap out of it. And it didn’t happen! Nobody walked out. Nobody participated. They planned the shit out of this thing: like muster points, parade routes, and whatever. And absolutely nothing happened; nobody walked out.

I went to meetings before and after, where I said: there’s a sense in which a big walkout or march is not something you can organize. Sometimes people get pissed off and mobilized and that’s what they do spontaneously. If they’re not going to do it spontaneously, you cannot organize them to do it. But what you can organize—as we know as Wobblies—you can organize people into direct democratic bodies that know how to leverage their power—we’re really the ones who hold all the power—to fuck up the business of the people who are screwing us over, whether they’re our educators or our employers. I’ve been tilting at windmills for the last couple months in New York to get people to think more along the lines of that model. And, in conjunction with that, move away from consensus and towards majority rule and Robert’s Rules, and that kind of thing. I’m just completely outnumbered and drowned out, and it’s not shifting.

The only thing that actually holds out some promise of shifting that now is what’s going on in Montreal. What’s going in Montreal is exactly what I just described; it’s a very Wobbly thing in a way. I went to Montreal myself during the Anarchist Bookfair, because I was tabling, and I met with some of the organizers, some of the members of CLASSE. Then, a comrade and I in the IWW wrote an article on exactly how they organized, the nuts and bolts of how they organized that shit in Montreal [see “Snapshots of the Student Movement in Montreal”]. I just disseminated that article as widely as I could in the student movement in New York and elsewhere. For the first couple of months, after people started paying attention to Montreal—which I would say is about May, after that strike had been going on for a while—there was a flood actually of sort of “protest tourism.” People from New York would go up to Montreal and participate in this grand spectacle that is the student strike there, and they would try to echo it with solidarity actions here. It’s so tangible how the message, the real core of it, would get perverted—because people would go up there and write articles and Facebook updates and stuff like that about how, ‘the revolutionary spirit in Montreal, we need that spirit to catch flame here in New York,’ and it’s like, no, we need to organize on the same model! That’s the real issue. But, I think that after awhile people are eventually catching on to the fact that the reason they pulled this off was because they used a very particular model of organizing it. And it’s not just a matter of spreading the revolutionary inspirational fire here.

This is catty, but one of the ways the Montreal strike got perverted when it came to New York is: in Montreal it’s called grève illimitée, which means unlimited strike, which is great, because it’s a play on unlimited in time and unlimited in scope. In New York, the anarchist insurrectos—there are unfortunately very few organizationally-minded anarchists in New York; they’re mostly insurrectionists—they created a big banner which they bring to all of their solidarity casseroles marches, and they have it on their Facebook page or whatever, and it’s “Infinite Strike.” That’s fucking meaningless! What’s “infinite strike”? By even saying the word “infinite,” you’re sort of deforming it beyond any recognizable shape whatsoever. But that’s so the sort of insurrectionist New York re-interpretation of grève illimitée, which is an invitation to other sectors to participate alongside, and it’s a statement to the Québec government that we’re not going away until we get what we want. And they perverted that into some meaningless “infinite strike.” So, that’s in a nutshell the problem with New York.

CW: With what you learned from going up to Montreal and talking with people about it, how are you trying to translate that into your organizing approach in what you’re doing with the student-worker organizing? Has anybody around NYC picked up that approach and started to do that?

Marianne: The student organizing that’s happening in New York, it does have a focus on issues: things like tuition and debt, as well as things like access to education. Definitely, at the most radical, critical forefront of that are the students at CUNY. And I would say that that’s because their institution has a real radical history. Unlike at the New School where we have only a radical intellectual history, CUNY has a real radical history. It used to have open enrollment, and it used to be run practically by committees of students and teachers. I think that that sort of democratic DNA kind of still lives in CUNY. So those students are radical in terms of things like access to education, issues of race and gender in education, tuition, and accessibility. And they have multiple assemblies at CUNY: grad students, undergrad students, there’s supposed to be one that’s CUNY wide. There are divisions that have cropped up between the undergrad and grad students because they belong to different demographic profiles. So, CUNY being a public and more accessible institution, the undergrad population tends to be lower income and more racially diverse. Whereas the graduate students tend to be more white, male, and elite, as most graduate student populations are. So, that’s a constant rift. But, as far as I know, these assemblies are still basically on the basis of voluntary participation.

Before describing what’s significant about Montreal, by contrast, and what I learned from speaking to the student organizers there, let me first say that a lot of people in New York, and I think elsewhere in the United States, when the Montreal student strike broke out, or when they started hearing about, they assumed that the reason why they were able to pull that kind of shit off in Montreal is because they are already organized into student unions that have some ability to bargain and negotiate—not just student associations but student unions. Whereas, in the United States, correct me if I’m wrong, student unions are actually illegal; you can’t have that kind of student union in the United States that has that kind of position. So, people thought, well that’s why they’re able to pull this stuff off in ‘commie Montreal.’ But, that’s not the case at all. The student strike in Montreal was able to be organized because they completely by-passed that infrastructure.

CEGEP Vieux-Montreal assembly – voting to continue the strike without conditions (August 13, 2012 – pic via The Link)

The way they by-passed it was in two ways. First of all, in institutions, organizing these assemblies—an organizer told me, they first started doing this as a university-wide kind of thing, and then they realized, no, we have to go more fine-grained than this, because otherwise you’re not going to get students to come out and participate. And if you don’t get students to come out and participate, the student body at large is not going to take the decisions of this assembly to be authoritative. So, they went more fine-grained, and they went to faculties, which we would call divisions or something here: so, faculty of law, faculty of science, etc. And then they realized, no, that’s still not fine-grained enough for the same reasons. We need to go more micro. We need to go down to departments, so, like, the philosophy department and whatever. Pretty soon, that model spread, and every department at every university had an assembly, and they were quite well attended. I think it was something like 40% participation. It was quite substantive, and it was very clear that everybody was welcome to come, and when people did come, there was no guarantee as to which way the vote was going to go. There were people who were drawn to come because they wanted a strike to happen, and there were people who were drawn to attend because they didn’t. One woman who I was talking to, her department voted not to go on strike. That’s how the strike was built. That’s one organizing level that made it possible: really, really drilling down and having direct democratic assemblies, which operate on the basis of majority rule, but with some trappings of consensus brought in. So, people were doing temperature checks, and they would do progressive stack, such as if they saw that people in one corner were disgruntled or disconnected. So, bringing in some lessons from consensus meeting and decision-making, but mostly on the basis of majority rule. And then, once it was voted whether or not to strike, that of course had to be enforced, and I’ll speak to that in a second.

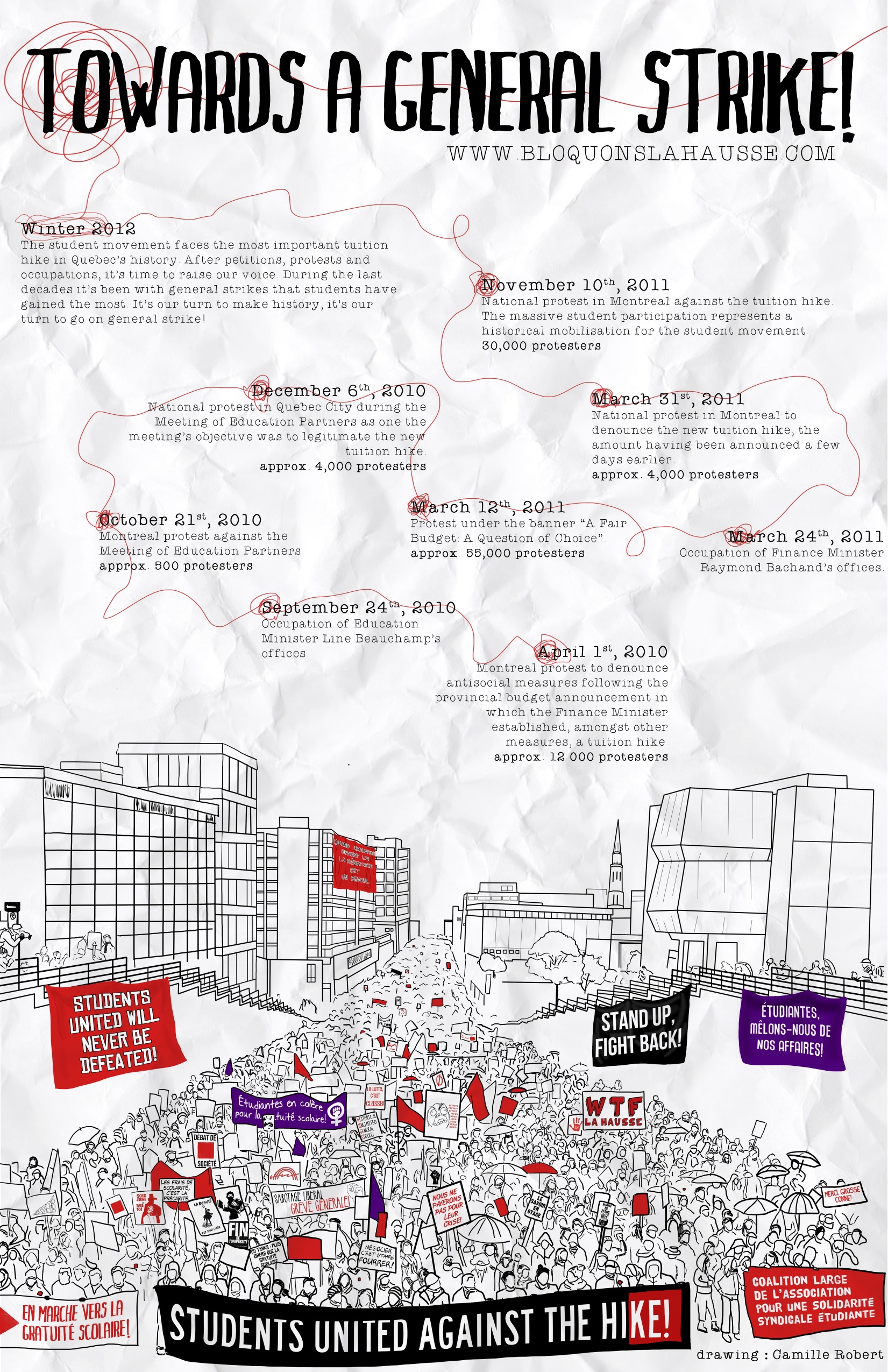

Poster with history of CLASSE via Stopthehike.ca

The other significant thing about the way they organized the strike was the fact that there was CLASSE (Coalition large de l’ASSÉ) [English website, French website]. In French, ASSÉ is a play on the word ‘enough,’ but it’s an acronym, ASSÉ, Association of Student Syndicalists, or something like that. It has an explicitly anti-capitalist and syndicalist bent. So, the coalition, CLASSE, that came out of that was a way for individual departments to affiliate with something larger without having to do that through their unions. Because they’re already organized into unions, their union belongs to an umbrella union organization. In Quebec, there’s the FECQ and the FEUQ and ASSÉ. So, if your union is affiliated with FEUQ then you can’t affiliate with FECQ, whereas CLASSE was open to any affiliation. So, you could be already a part of the FECQ or the FEUQ but you’re welcome to also join CLASSE. So, they had a different way of coagulating all of the student groups. That’s the organizing model. That’s how they were able to pull it off.

A friend of mine, who I’d met in Montreal, made a really, really important point the other day. She put a link on Facebook to an article that was describing how incredibly difficult and frightening and onerous and shitty it was, once they had voted to strike in a particular department, to enforce that strike. She said, you’d get yelled at, you’d get assaulted, you’d get insulted, you’d get students mad at you, professors mad at you. And they figured out one of the better ways of maintaining the strike discipline, in other words, enforcing the picket line, was not to prevent students from going into the classroom but just to prevent professors from going into the classroom. And the professors who are sort of softy-lefty liberals are kind of like, ‘alright, sure, I won’t cross the picket-line because, pat self on back, I’m cool that way, and now I have a couple hours off, and I’m part of a union too, so I kind of vaguely respect picket lines’—whereas, if they tried to enforce the picket line against students, students would get really, really pissed at you, defending their exercise of their time, or whatever. Even though they knew that a strike had been voted on.

So, those are really important and really hard lessons that people here need to take from Montreal. Drilling down and actual use of assemblies to make decisions and not sit around and just have a meeting and talk about ‘how difficult debt is to deal with and screw the administration and let’s create a protest.’ But, vote on a real, rubber-meets-road decision, like, ‘are we going to shut down their business? And if we are, how are we going to enforce that?’

CW: So, how do we build something like CLASSE in the US? There are definitely a lot of differences of the context in Quebec. I wonder if you think it’s possible. How can it be done to build up to something like that here? Would we need to build an ASSÉ type radical student union first?

Marianne: That’s a really good question. It’s sort of the question of, how do you create something out of nothing? Because, yeah, we’re starting from zero. And, the other way we’re starting from zero is that Montreal has a real solid history of these kinds of strikes—this exact kind of event. They had it four or five years ago. They had one seven years or ten years ago. They have them on a regular basis. People like to point out, ‘well, tuition is lower in Quebec than anywhere else, therefore how can you complain?’—which is that ridiculous argument that somehow two wrongs make a right. Why not lower everybody else’s tuition to Quebec levels rather than raising it to Alberta levels, for example? The fact that their tuition is so low is a reflection of the fact that they’ve always historically had this really vibrant, really militant student movement, one that is willing to strike and directly disrupt, and not wait for the leadership of the business unions.

By the way, the business unions of Quebec and the umbrella associations of business unions of Quebec, like the FTQ and the CLC, documents have been leaked about how they are explicitly talking amongst themselves about not supporting the strike anymore—because it’s circumventing their mandate [see article: “CLC Sells Out Students”]. They’re talking about not sending donations, not doing solidarity actions, and they’ll cloak it in the language of ‘Quebec has its sovereignty, Quebec has a certain independence, and doesn’t want to be dictated to by the rest of Canada,’ so they repeat that in the labor movement, like, ‘don’t overstep your bounds and go support the Quebec student movement because that’s their own thing.’ Anyway, the labor bureaucracy is completely trying to sabotage the Quebec student movement because they’re fucking embarrassed by it. It shows how impotent they are and it shows how the real way of organizing is anarcho-syndicalism, basically.

So, that leads into my answer to your question, which is, there’s a sense in which we have a big problem because we’re starting from scratch and we don’t have that history and we don’t have that experience of experienced organizers to mentor younger organizers in the United States. But, having said that, you can create an anarcho-syndicalist organization. In other words, it’s kind of great that they’re not relying on the official labor bureaucracy to carry out this strike. Because, yeah, we don’t have one of those in the US, but we don’t fucking need that. That’s not actually how these things are organized. In fact, it means that there’s possibly less of an impediment, because if we don’t have those assholes to deal with who are going to try to undermine and sabotage us, then it’s one fewer roadblock. We can just do this from scratch and out of the blue, and have it hopefully work.

But, in terms of concrete steps: absolutely talking about and disseminating exactly how they are doing things in Montreal, trying to launch that kind of model here, trying to organize assemblies in departments here. You’re trying to import a model that is, in a way, foreign, although it is a model that would be endorsed, supported, and embraced in theory by a lot of students here. But, now we just have to get the sort of traction for the actual, on-the-ground creation of that, and use people’s wide-eyed inspiration of Montreal to import the model.

CW: To use a cliche, I feel like, ‘we are the ones we’ve been waiting for.’ There might only be a few dozen people across the country who are really inspired to do this. Maybe we could come up with some kind of plan together. We do have some resources with our IWW organization, also, such as trainings. This is one thing I’m really excited about trying to make happen: to modify the IWW organizer training to make it specific for the university-organizing context, particularly for students and student-workers. I think having a concrete project like that could be kind of a focal point for that kind of organizing to kick off. That would be a way to build on the experience that IWW organizers have.

Marianne: It goes back to the sort of basic lessons of the IWW. It comes down to training, because that’s what the gap is. Let’s not fetishize the gap between where we are and where we need to be—as a matter of consciousness or as a spiritual matter. It’s a matter of training—people not actually effectively having the concrete skills to carry forward the struggle in this way. The dissemination of those trainings: the IWW should absolutely be putting together a training for organizing at the level of education. The IWW Montreal is actually a very decent branch, and there are members that are part of CLASSE that I met when I was there; they’re awesome, and I assume they’re at least partly involved in this. Yeah, we put together an educator training, we run that training, and disseminate that training. The other dimension is bringing people into the fold, arming them with the skills but bringing them into the fold. And that gets back to sort of Organizer 101 too. You go and you speak to people directly about the issues that they’re facing, and you sort of agitate them, and whip them up, and you talk about what some of the solutions are, which we’re getting sort of directly broadcast out of Montreal. And then you start organizing. That means talking to people individually. In my department, we do have a forum—a student body that’s left-leaning and that meets regularly—going to that and bringing up the model of how they’re doing things in Montreal, and suggesting that as a way we get together. Maybe, to cement that model, holding some kind of department intervention or direct action that gets us some kind of small result. Inspire people with that model and to continue on with that model. In a way, what you’re saying makes me think of how this is all Organizing 101.

A lot of students haven’t been involved in union organizing because they’re students—they’ve been in school their whole lives, so they haven’t been particularly involved in workplace organizing. Part of the reason I happen to have been is because I’ve been working the whole time that I’ve been in school, almost full-time. I think that you can kind of sense that different sensibility among students who have only been students or who are living as students on the basis of loans or parental support—where being a student is a really subordinate position, where you’re kind of a consumer, but you’re completely passive, and you’re also not the source of production. So, it’s hard to have any sense of your own power in that situation. It’s a really passive role, and unfortunately, I think that lends itself to a certain lack of experience, and even a sort of lack of conceptual imagination when it comes to organizing. It’s almost like the model in their head in some sense is speaking out in class, because that’s the environment that they’re used to, and that’s how they know how to make an intervention and get some attention and re-direct things. So, I feel that a lot of student organizing is almost on that model of speaking out in class. It’s, you know, ‘let’s demonstrate.’ But, having said that, there’s huge potential there. Look at Montreal.

An interview by Class War University with Marianne Garneau, Wobbly and co-author of “Snapshots of the Student Movement in Montreal”. Originally posted on the Class War University website on 31st August 2012.

Comments