A short account of the successful strike in 1888 by thousands of unorganised female workers at the Bryant & May match factory in London.

In June 1888, Clementina Black gave a speech on Female Labour at a Fabian Society meeting in London. Annie Besant, a member of the audience, was horrified when she heard about the pay and conditions of the women working at the Bryant & May match factory. The next day, Beasant went and interviewed some of the people who worked at Bryant & May. She discovered that the women worked fourteen hours a day for a wage of less than five shillings a week. However, they did not always received their full wage because of a system of fines, ranging from three pence to one shilling, imposed by the Bryant & May management. Offences included talking, dropping matches or going to the toilet without permission. The women worked from 6.30 am in summer (8.00 in winter) to 6.00 pm. If workers were late, they were fined a half-day's pay.

Annie Besant also discovered that the health of the women had been severely affected by the phosphorous that they used to make the matches. This caused yellowing of the skin and hair loss and phossy jaw, a form of bone cancer. The whole side of the face turned green and then black, discharging foul-smelling pus and finally death. Although phosphorous was banned in Sweden and the USA, the British government had refused to follow their example, arguing that it would be a restraint of free trade.

On 23rd June 1888, Beasant wrote an article in her newspaper, The Link. The article, entitled White Slavery in London, complained about the way the women at Bryant & May were being treated. The company reacted by attempting to force their workers to sign a statement that they were happy with their working conditions. When a group of women refused to sign, the organisers of the group was sacked. The response was immediate; 1400 of the women at Bryant & May went on strike.

William Stead, the editor of the Pall Mall Gazette, Henry Hyde Champion of the Labour Elector and Catharine Booth of the Salvation Army joined Besant in her campaign for better working conditions in the factory. So also did Hubert Llewellyn Smith, Sydney Oliver, Stewart Headlam, Hubert Bland, Graham Wallas and George Bernard Shaw. However, other newspapers such as The Times, blamed Besant and other socialist agitators for the dispute.

Besant, Stead and Champion used their newspapers to call for a boycott of Bryant & May matches. The women at the company also decided to form a Matchgirls' Union and Besant agreed to become its leader. After three weeks the company announced that it was willing to re-employ the dismissed women and would also bring an end to the fines system. The women accepted the terms and returned in triumph. The Bryant & May dispute was the first strike by unorganized workers to gain national publicity. It was also successful at helped to inspire the formation of unions all over the country.

Annie Besant, William Stead, Catharine Booth, William Booth and Henry Hyde Champion continued to campaign against the use of yellow phosphorous. In 1891 the Salvation Army opened its own match-factory in Old Ford, East London. Only using harmless red phosphorus, the workers were soon producing six million boxes a year. Whereas Bryant & May paid their workers just over twopence a gross, the Salvation Army paid their employees twice this amount.

William Booth organised conducted tours of MPs and journalists round this 'model' factory. He also took them to the homes of those "sweated workers" who were working eleven and twelve hours a day producing matches for companies like Bryant & May. The bad publicity that the company received forced the company to reconsider its policy. In 1901, Gilbert Bartholomew, managing director of Bryant & May, announced it had stopped used yellow phosphorus.

Primary sources

(1) Annie Besant, The Link (23rd June, 1888)

Born in slums, driven to work while still children, undersized because under-fed, oppressed because helpless, flung aside as soon as worked out, who cares if they die or go on to the streets provided only that Bryant & May shareholders get their 23 per cent and Mr. Theodore Bryant can erect statutes and buy parks?

Girls are used to carry boxes on their heads until the hair is rubbed off and the young heads are bald at fifteen years of age? Country clergymen with shares in Bryant & May's draw down on your knee your fifteen year old daughter; pass your hand tenderly over the silky clustering curls, rejoice in the dainty beauty of the thick, shiny tresses.

(2) Anonymous letter received by Annie Besant from a Bryant & May worker (4th July, 1888)

Dear Lady they have been trying to get the poor girls to say that it is all lies that has been printed and trying to make us sign papers that it is all lies; dear Lady nobody knows what it is we have put up with and we will not sign them. We thank you very much for the kindness you have shown to us. My dear Lady we hope you will not get into any trouble on our behalf as what you have spoken is quite true.

(3) Interview with Bartholomew Bryant in The Star newspaper (July, 1888)

Q: What is the cause of the strike?

A: Why, a girl was dismissed yesterday; it had nothing to do with Mrs. Besant. She refused to follow the instructions of the foreman, and as she was irregular anyway, she was dismissed.

Q: Is it not very unusual that all the girls should strike because of one?

A: Yes, but I've no doubt they have been influenced by the twaddle of one.

(4) The Times (June, 1888)

The pity is that the matchgirls have not been suffered to take their own course but have been egged on to strike by irresponsible advisers. No effort has been spared by those pests of the modern industrialized world to bring this quarrel to a head.

(5) Henry Snell, Men Movements and Myself (1936)

In July 1888 the girls employed at a match factory in the East End of London came out on strike. These courageous girls had neither funds, organizations, nor leaders, and they appealed to Mrs. Besant to advise and lead them. It was a wise and most excellent inspiration. Money was quickly subscribed for their support and, within a fortnight, the employers considered it prudent to concede their demands. The number affected was quite small, but the matchgirls' strike had an influence upon the minds of the workers which entitles it to be regarded as one of the most important events in the history of labour organisation in any country.

(6) William Stead, Pall Mall Gazette (July, 1888)

The story is full of hope for the future, illustrating as it does the immense power that lies in mere publicity. It was the publication of the simple story of the grievances of the match girls in an obscure little halfpenny weekly paper called The Link which did the work.

From http://spartacus-educational.com/TUmatchgirls.htm

Comments

I think that Annie Besant is

I think that Annie Besant is given too much credit here. She did not lead the Matchwomen in their campaign. They organised themselves to campaign and strike without the help of middle class socialists. They were proper working class East End Women who could hold their own. Although Annie did write about their predicament. An interesting event which needs to be spoken about more, all the same.

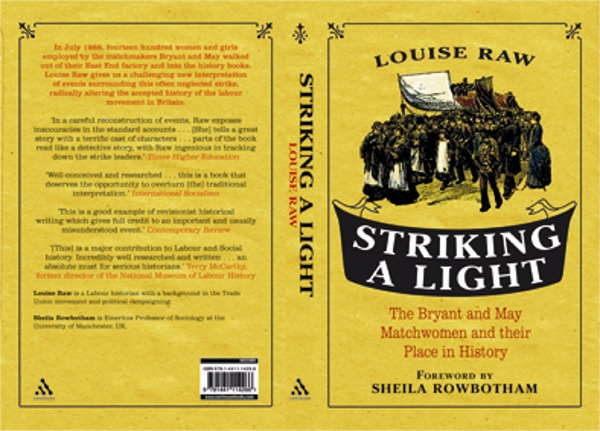

Yes. The study by Louise Raw:

Yes. The study by Louise Raw: Striking a Light is a great historical work that gets to the story of the women who organised on and off the job, before Besant became a sort of figurehead. A good read