An article on the 1980 uprising in St. Pauls, Bristol and the music scene which flourished there after with excerpts from contemporary literature.

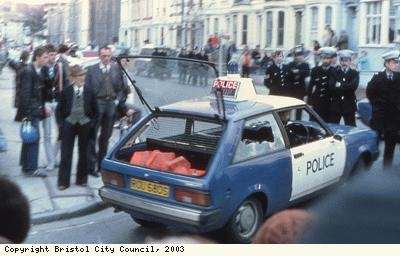

The current ConDem government has faced riotous opposition six months after coming into office. The last time a new Conservative government came in in 1979 it took almost a year for this state of affairs to arise, but the riots were much more ferocious than anything seen in recent years. In the St Paul's area of Bristol in April 1980 the riot saw police cars and a Lloyds Bank set on fire. Interestingly in terms of the broader themes explored at History is Made at Night, the riot was sparked by the police raid on a cafe in the context of broader conflicts about racism, black sociality and licensing laws. 134 people were arrested - 88 black and 46 white - so it is misleading to describe it as a race riot even if police racism was a major factor. Remarkably, in the most serious trial arising from the riot, the jury failed to convict 16 people charged with 'riotous assembly'. The collapse of the trial in March 1981 was followed a month later by rioting in Brixon and then a wave of summer uprisings.

The first document is an extract from the book Uprising! The Police, the People and the Riots in Britain's Cities by Martin Kettle and Lucy Hodges (London: Pan Books, 1981):

'St Paul’s is an area to which black people from all over the city come for parties, shebeens (illegal drinking clubs) and to play ludo, dominoes and pinball machines at the Black and White Café, the premises where the spark for the riot was lit. They come because there is nowhere else to go. Much of the activity is perfectly lawful and, even where it is not, it involves behaviour such as illicit drinking and cannabis-smoking which does other people no harm.

If the district is the focus for black social life in the city, the Black and White Café in Grosvenor Road, the ‘frontline’, is its nerve centre. When the riot broke out, it was the only black café (it is in fact run by a black and white husband and wife team) which had not been forced out of business for contravening local authority health regulations or for similar reasons. But it had had its licence to sell alcohol removed. A seedy joint created out of the ground floor of a terraced house, the café was of great importance to the black community. It was the only bit of territory they had left and they were prepared to fight for the right to do what they liked there...

What brought hundreds of black and eventually white Bristolians up against the law on 2 April, 1980, a day when the schools closed at midday, was a police raid on the Black and White Café. This had happened many times before but serious violence had never broken out though it had in London in connexion with the Mangrove and Carib clubs). On the Second, as the occasion become known, thirty-nine policemen armed with search warrants for drugs and illegal consumption of alcohol moved in; the majority were to go into the café and the rest were to be held in reserve...

What they could not have known was that tension was high in the Black and White that day. There was much talk about a St Paul’s youth who had been arrested on ‘sus’ in London and was appearing in court the following day. Young blacks were angry about the ‘police harassment’ and talked of going to London to protest.

At about 3.30 p.m. the officers, the drugs squad in plain clothes and the rest in uniform, raided the café. They searched the place and questioned the twenty customers, searching some of them as well. Bertram Wilks, the café’s owner, was arrested and taken away in handcuffs, protesting loudly, to be charged with possessing cannabis and allowing it to be smoked on his premises. The police found large quantities of alcohol, including brandy, vodka and 132 crates of beer which they proceeded to load into a van in front of a growing crowd outside. The loading took a long time because there was so much liquor. As each crate was humped into the van, the crowd grew more restless, and when the van left a bottle was thrown, but there was no real violence as yet.

A man complained that his trousers had been torn by a police officer in the café, an allegation which was later canvassed as the reason for the riot, and drugs squad officers made a run for it clutching their booty. This was what really seemed to annoy the crowd. ‘Let’s get the dope, let’s get the drugs squad,’ they are reported to have shouted. Missiles were thrown in earnest at a police car and at officers, and the riot had begun. The violence spread quickly: officers outside the café took refuge inside under a steady hail of bricks, bottles and stones from the crowd of black and white youths which had grown to about 150 (others were looking on) on the grassy area opposite.

The police radioed for help and at about 5.30 p.m., two hours after the raid began, reinforcements arrived, assembling down one end of Grosvenor Road and marching down the road to rescue their besieged colleagues. This was a hazardous operation, with officers coming under a terrific barrage and being forced to take cover under crates and behind dustbins. It was the start of the really serious violence. As a black prostitute told the Sunday Times: ‘They came down the road, left right, left right, like they were on parade. They had dogs with them. When they came in front of the café, we let them have, it.’ The mistake the police may have made was to try to impose control with too few men. The marching column contained only 100 police and, on this interpretation, was a positive incitement to the angry crowd. Defence counsel at the riot trial months later suggested that the police had provoked the crowd by their military- style tactics. The police said, in turn, that they hoped this show of strength would disperse the crowd. It did no such thing'.

The second document comes from The Leveller magazine in 1980, a very radical piece from a member of its collective who later became... well I won't spoil it, read it first before you skip to the end to see who wrote it:

'Just when it had become fashionable for world-weary, elitist, metropolitan lefties to claim that class struggle was somehow ‘old-wave’, the Bristol race riots have put it triumphantly back on the political agenda in its most classic form - urban insurrection. The riots confirmed that the front-line is still where it has always been, which is not in animal liberation groups or whatever happens to be the current O.K. cultural preoccupation. The front-line is located where people are in struggle; where working people under all types of pressure, racism, capitalism in crisis, clash with the forces of the state.

The riots are probably the most politically progressive thing that will happen all year. But because they are difficult to assimilate into conventional political thinking they run the risk of being dismissed as almost a sideshow. The ‘New Statesman’, at a loss as to quite what to say about them, chose to say nothing at all. Paradoxically the state probably has a clearer idea of their significance than the white left establishment. Social workers, vicars, race relations officers, local councillors — in other words the whole structure of social control - wrung its collective hands and wailed ‘How could this have happened in Bristol, it had such good community relations?’ Someone ought to tell them that the race relations industry has increasingly little to do with the reality of life as it is lived by most black people and as such is not a barometer of anything, still less a cure or even a palliative. They could try asking black people from St. Pauls. They are scathing about ‘community leaders’ who are unknown to the community, black social workers who are primarily concerned with holding down their jobs and the local Community Relations Council. This body has allegedly been involved in deals with the police which would involve handing over lists of names of rioters in return for police promises to confine prosecutions to names on the list.

In parliament politicians tried to incorporate the riots into their own sterile Westminster games. Labour MPs blamed Tory policies for the riots, ignoring not only the fact that Geoffrey Howe and Willie Whitelaw are carrying out monetarist and law-and-order policies which were initiated under Denis Healey and Merlyn Rees, but that the Labour party record on fighting racism is just as bad as the Tories. The extra-parliamentary left has followed its traditional opportunism towards black struggles. At the march commemorating the anniversary of the death of Blair Peach the ANL [Anti Nazi League]— ever sensitive to fashion — had a black youth from Bristol on the platform.

The response of the state to Bristol has been more considered. It is clear that the other big city police forces are very cross indeed with the Avon and Somerset force for failing to stand and fight it out in St. Pauls. The Metropolitan police — in a novel exercise in community relations — has called in key black activists to warn them against following the Bristol example.

The significant thing is that the people of St. Pauls were able to hold it for five hours against the police, not just because they technically outnumbered them but because a whole system of police control, which includes surveillance had broken down. They won’t be caught like that again. The lesson of Bristol for the police is not only the need for bigger and better SPG type units in all the big cities but the need to strengthen the whole submerged infra-structure of police control: surveillance, phone-tapping etc.

Black people in St. Pauls dislike talk of the riots as a defeat for the police. They say the police victory is only just beginning. Over a 140 people have been arrested on charges connected with the riots — the first batch of them came up in court on May 1st. It seems there will be extensive use of conspiracy charges and the community is having great difficulty co-ordinating its defence because of the lack of grass-roots organisations and committed lawyers in Bristol.

The riots have had interesting reverberations within the black community as a whole. My mother is a black working class lady nearing 60. Eminently respectable and conservative-minded, she was pleased and excited by the ITN film of policemen running away from black youth and said firmly: ‘It shows they can’t push us around any more’. The riots politicised my mother and others like her and the state is well aware they posed a direct threat to its power — the more so because they were entirely spontaneous. But those on the white left who won’t learn the lessons of Bristol and insist on incorporating what happened into their own world-view may well find that the revolution happens without them'.

(The Leveller, no.38, March 1980 - written by Diane Abbott, later Labour MP)

[youtube]Wdyo16VMhIQ[/youtube]

So what about music? There is actually a direct line between the Bristol riots and the Bristol music scene that exploded later in the 1980s and early 1990s. Quite a few people from that scene were amongst the estimated 2000 on the streets that night. More to the point the riot carved out a social space in which music flourished. According to the excellent Port Cities:

'In the early 1980s competing ‘crews’ like The Wild Bunch (who later became Massive Attack), 2Bad, City Rockers, UD4 (Roni Size’s brother) and FBI Crew were battling it out on home-built speaker systems, modelled after those in Jamaica in the Caribbean. The Wild Bunch became legendary for their much-attended parties at which their music sets combined punk, reggae and Rhythm and Blues. They played at local events, such as St Pauls Carnival and in disused or empty buildings in or close to the St. Pauls area. After the St. Pauls riots in 1980, the police avoided the area, which made such gigs possible'.

Clifton Mighty, brother of Ray Mighty of 'Smith and Mighty' fame, was one of those acquitted in the riot trial (though he was still facing hassle from the police twenty years later).

[youtube]jcFuSDcBh8w[/youtube]

Posted on the History is made at night blogspot on Friday, December 17, 2010

Comments

I wonder what the shadow Home

I wonder what the shadow Home Secretary thinks of it now...

Crucial to defeat the lie of

Crucial to defeat the lie of Race riots and say what really happened.An uprising that is rarely mentioned and the 1985 uprisings that would bring Class to the fore and expose the Neoliberal con just as Grenfell has.The Uprisings were and are an inspiration.Does anyone know of any good books on them?

Things we have on the site

Things we have on the site already:

https://libcom.org/library/rebel-violence-v-hierarchical-violence-uk-1985-86

This covers Notting Hill '86 https://libcom.org/history/once-upon-time-there-was-place-called-nothing-hill-gate

This on the aftermath of Broadwater farm: https://libcom.org/library/tottenham-3-denied-right-appeal-red-menace

That's not that much overall, so if you come across something it'd be good to add to the library.

via google I just found http://berniegrantarchive.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2015/12/Gifford-Report-2-Contents.pdf - that's from the independent inquiry but it might be worth reproducing for historical reference - didn't read any of it yet.