Anyone who has followed the Occupy Movement will know how many of those involved blame just the banks and that this has opened the door for all sorts of currency cranks and money bugs. Obviously, everybody here knows that mere banking or money reform is not going to make any basic difference to the way the capitalist economy works, but we still need to take on and refute these theories.

Here are two attempts to do so from a Marxian perspective:

http://www.metamute.org/editorial/articles/john-maynard-nothing

http://www.worldsocialism.org/spgb/socialist-standard/2010s/2012/no-1298-october-2012

(Shamelessly self-promotion)

(Shamelessly self-promotion) I gave a talk on this topic a few years back, which you can read here: http://libcom.org/library/fictitious-capital-new-fangled-schemes-public-credit

Good article. But of course

Good article. But of course banks' dealing in "fictitious capital" (capitalised future income streams) is not the same as banks lending real savings. Fictitious capital and bank credit are not the same, not that you suggested they were.

More on Marx's writings on finance here.

Some simple facts against the

Some simple facts against the currency cranks (Bloomberg).

In-depth discussion of several leading easy money advocates here

In other

In other news:

http://www.huffingtonpost.co.uk/2012/12/18/queen-asks-george-osborne-gold_n_2321666.html

There's some conspiracy mongering around it, but I think with the fact that historically the price of gold was openly "manipulated", it be might be interesting to look at the role of gold lending by central banks (which is undisputed) in the price of gold or the value of currencies.

Perhaps worth adding another

Perhaps worth adding another useful contribution from alb here regarding the recent Bank of England/Financial Conduct Authority report on the 2008 failure of the UK HBOS bank:

www.worldsocialism.org/spgb/socialist-standard/2010s/2016/no-1337-january-2016/hbos-horse-bolted

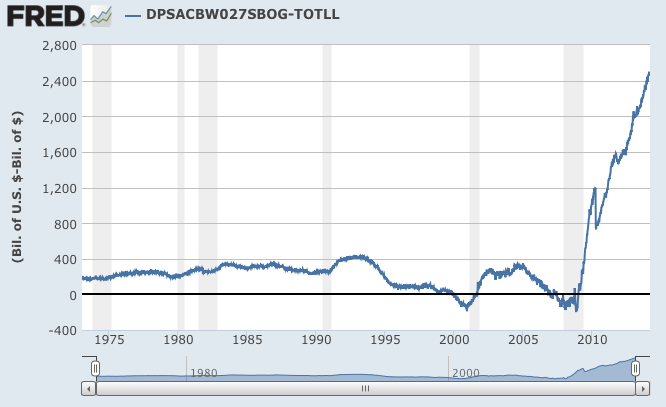

"a graph that shows the

"a graph that shows the result when we subtract loans and leases from deposits:"

[quote=some blogger]For the years between 1975 and mid-2008, bank deposits exceeded lending by an average of $205 billion.[/quote]

^the above graph was to

^the above graph was to counter the claim that banks can create more loans than their deposits. The two points of exception (the dates just after 2001, and around the 2008 crisis) when the amount of total loans exceeds deposits, would require some explanation by a more detailed look into the balance sheets.

--

Just to again correct a smaller mistake, but an outrageous one, made by Hillel Ticktin and repeated every time (eg in this lecture of the CPGB summer school: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=7uE74NjDIy8) of a supposed staggering 27 trillions of dollars parked (ie not invested) at the Bank of NY Mellon. Hillel's point is about money not being invested, but I think his example is clearly wrong. I found that:

On the balance sheet of the Bank of New York Mellon total deposits for 2012 amount to 'only' about $246 billion:

http://www.bnymellon.com/investorrelations/annualreport/

The figure of $27 trillion refers to “Assets under custody or administration (AUA)”, which isn’t exclusively cash. It’s likely also much stocks (and as the Dow Jones from 2002 to 2008 almost doubled, and since collapse again recovered, the AUA would follow). The annual growth of AUA at BNY Mellon hasn’t accelerated compared to before the crisis (looking back prior to the merger of Mellon with the bank of New York in late 2006, to their combined AUA), see 2007 report page 4 (chart shows growth from something under $10 in 2002 to $23 trillion in 2007). The year of crisis 2008 saw a decrease to $20.2 trillion. 2009 (22.3 trillion) still no full recovery to the 2007 figure. 2010 growth to 25 trillion, 2012 lists 26.2 trillion. That is slower compared to the (hypothetically combined) growth before 2007. So I think Ticktin’s mention of $27 trillion should be seen as referring to the increased amount of AUA since the early 2000s. And as I mentioned the stock market increased about the same rate, so this growth is probably not mostly due to cash which is “deposited”.

Noa, Check the FDIC

Noa,

Check the FDIC statistics "archived industry trends" at https://www.fdic.gov/bank/statistical/stats/

The data in this series starts in 2001, and for 2001-2008, commercial bank and savings institutions loans exceed domestic deposits.

Of course, banks can lend more money than they take in in deposits, just as a corporation can spend more on production than it takes in in revenue by issuing short-term debt (commercial paper) and long term debt (bonds).

As for Ticktin, nobody has 27 trillion in cash assets on hand, not the People's Bank of China, not BOJ, not JP Morgan Chase, not Apple, or Exxon, not anybody.

Indeed that link shows a

Indeed that link shows a (slight) excess of loans over deposits, but I think more complete (because include perhaps also non-insured deposits) are the figures that I base myself on:

Assets and Liabilities of Commercial Banks in the United States

http://www.federalreserve.gov/releases/h8/

eg 21 December 2005: http://www.federalreserve.gov/releases/h8/20051230/

It shows item 5 (Loans and leases in bank credit) is below item 17 (Deposits), respectively $ 5,445.2 billion vs. $ 5,747.3 billion.

Perhaps the difference with the FDIC figure is because that loans are more often insured than deposits?

FDIC doesn't insure loans; it

FDIC doesn't insure loans; it only insures deposits.

There must be a difference in

There must be a difference in the way that banks report their figures to the Federal Reserve and to the FDIC, but I get a literal headache trying to figure out what accounts for that difference. I hope it's not dyslexia.

Noa, When you say banks can't

Noa,

When you say banks can't loan more than they have on deposit, do you mean banks are prohibited from doing so by statute, or by the "economic laws" inherent in capitalism?

I know of no statutory requirements that tie loans/assets to deposits.

I think we can abstract from

I think we can abstract from inter-bank loans (because basically that's borrowing another bank's deposits to be able to extend more loans than the bank itself has on deposit).

I'm opposing the claim of that group of economists (eg Richard Werner, Randall Wray, probably also Steve Keen, etc. - in German there is Mathias Binswanger, etc. as listed here), which as I understand it, says that bank create money out of nothing.

It would be helpful if someone can find figures of British (or other country) total loans vs deposits to see whether there can be more loans than deposits (again, in total). If there is no such evidence, than I think it's an easy refutation of the fallacy that banks create money out of nothing.

Banks don't create money out

Banks don't create money out of nothing, anymore. Central banks authorize the printing of money. Back in the day when banks issued their own scrip, they were issuing promissory notes.

Banks don't issue loans based on the amount of money deposited in the bank. They make loans on the basis of their own access to capital markets-- i.e. debt.

Banks have issued about 15.3 trillion in bank debt. That amount certainly exceeds amounts on deposit by at least a factor of 5 and probably closer to 10.

S. Artesian wrote: Banks

S. Artesian

Actually, they make them from both, i.e. both deposits (from outside) and from what they themselves borrow from the money market. So, while it is true, that banks are not restricted to what they can lend by the amount that has been deposited with them, this does not mean that they can create what they lend out of nothing. If they lend more than their deposits they have to have obtained the money elsewhere.

There is a measure of this -- the loan to deposit ratio which is a measure of how much a bank depends (or not) on borrowing rather than deposits for making loans.

Simple question; prior to the

Simple question; prior to the bank's reliance on capital market funding, where was that (capital market's) money originally located, and was it doing nothing? It seems the assumption made (by Artesian and Alb) is, that it was not on deposit at a bank.

So did the money come from under the capital market's mattress?

http://www.metamute.org/edito

http://www.metamute.org/editorial/articles/john-maynard-nothing

On a related note, if any of you want to comment, this article on Mute makes an argument about "monetary reformism", the idea that it is primarily the system of money creation which needs to be fixed to bring a just society into being, and/or that the current crisis is a result of 'evil banks producing money from nothing'.

Intuitively I am swayed by the author's argument against this fairly widespread but non-radical idea, but my econometric, how banks-really-do-it knowledge isn't that fancy, so I might be wrong.

On a more complex level, I'm also curious how this argument is related to that of fictitious capital as used by Marx, as the multiplication of titles to wealth, which circulate as value, are bought and sold but in fact are only future claims on the wealth actually produced. As the heaping up of unrealizable claims to wealth it is one of the sources of systemic instability, creating both winners and losers among value-owners, but I am not at all sure how the processes which give rise to 'monetary reformism' type of ideas relate to this concept in all its depth.

As alb says, fictitious capital and bank credit are not the same, but I wonder how they relate on the banks balances, assuming that an unknown portion of any large capitalist company's accounted possessions consists of fictitious value. Can the paper value of these possessions serve as the backing for credit which a bank gives out to its clients? In short, do the values of wealth titles figure as 'real wealth' which banks use to back up new credit issuance? Or is there some more limited basis for credit issuance? If the first is the case, they would be handing out credit on the basis of value which might be swept out from under them, so the alleged nothing on which credit is based is something real, ie. is still recognised as representing real value, and used as such in sober accounting as dependable guarantee of future income. On the other hand, it is a claim to wealth which is not recognized as possibly partly fictitious, so the backing for the credit is also partly lacking.

Don't hesitate to tell me if I'm completely out in the woods with this attempt, of course. :)

Noa Rodman wrote: Simple

Noa Rodman

I don't assume anything. You argued that banks "can't" lend more than they have on deposit. What is the origin of the "can't"? Statutory or market?

Why can't a bank lend more than it has on deposit? That's the issue requiring clarification. The graph you produce shows, for a period, loans exceeding deposits, so clearly there's no statutory prohibition.

And market "prohibitions" are just that-- market, and therefore mutable, cyclical, contradictory.

That loans are usually less than deposits isn't the issue.

You might as well be arguing that a corporation can't spend more than its cash and cash-type assets on hand.

As for creating "money out of nothing.." nobody claimed that. But money can be created by leveraging assets, earnings, cash flows, and leverage to ratios of 30:1 as occurred prior to the 2008 contraction. Remember MBS? ABS? CDO? CLO? Structured Investment Vehicle? Off-Balance Sheet entities? etc. etc.

Not to mention, do you mean commercial banks, investment banks, savings banks?

I mean total banking industry

I mean total banking industry of a country Artesian (to repeat myself). Indeed for two periods that I mentioned the total loans exceed deposits in the US (would be nice to find these figures going back decades for other countries too), and that I need to explain (2008 perhaps related to crisis, but there's also the period 2001ish).

The question spacious asks I think is whether in fact "money can be created by leveraging assets" etc. like you say. They can create these credit instruments, but I think the banks sold them to others on the market precisely to get money (i.e. that money to buy the assets is not created by them). I don't think fictitious capital can be discounted by today's commercial banks to issue credit money/banknotes (spacious put the finger on the question).

Noa Rodman wrote: Simple

Noa Rodman

In the end of course it came from profits made by capitalist enterprises in the real economy (created by the unpaid labour of the workers). The point is that it does not matter where it came from, but that it is there and is available for banks to borrow and relend at a higher rate of interest. That's what banks do: borrow money at one rate of interest and relend it at a higher rate. Deposits to a bank are in effect (and in law) a loan from the depositor to the bank.

S. Artesian

The word "created" here is ambiguous. Banks can and do engage in these activities as well as their core activity of borrowing to relend and they do "make money" out of this in the sense such speculative activities generate an income for them. But this is not "creating money" in the sense that is usually used in discussions about whether or not banks can "create money" out of nothing. Also, of course, to engage in such activities banks already have to have the money, whether from their capital, the money market or even their depositors.

But you seem to think that

But you seem to think that the capital market keeps its money (that can be made available for banks to borrow) stored somewhere outside the banking system prior to when the banking sector actually applies for capital market funding. So this money wasn't yet on deposit at the banks (which as you say is in effect a loan of the depositor to the bank), according to your assumption. So I'm asking not where the capital market gets its money, but where does it store it, prior to when it lends it to banks?

What about that bank of

What about that bank of England paper arguing that private banks do indeed create money by lending? Also that banks only have 3% coverage of their loans. (Sweden) these are figures and arguments basically pulled out of my arse but I have vague recollections that they are from mainstream *reputable" sources.

I know nothing and don't really follow this stuff but I've definitely read things along these lines.

Quote: The question spacious

All these instruments are created with one purpose--- to be exchanged for money. They seek some sort of realization as money. So whether or not the banks, or any financial institution, including life insurance companies, brokers, etc. "create" money is immaterial. They are creating instruments of exchange. Out of nothing? Yes and no-- that is to say the instruments always have either a direct, or an indirect link to some sort of asset or both, even if the asset is simply, or most particularly, the general direction of the economy. Letters of credit, notes, bonds, asset backed securities, can themselves be exchanged in secondary markets for cash.

The instruments of credit can and do function as money.

So, for example, the notes, leases, bonds secured by container ships, and container shipping rates are no more "fictitious" than the container ships and container shipping rates themselves. Do container ships make "money out of nothing"? Of course not, but when the ships fail to make money period, then their capital value is dramatically depreciated, as is the case with the price of container ships today vs. 2007. Does that make the capital embodied in a container ship "fictitious." Of course not. It means capital has devalued itself.

The entire issue of "fictitious capital" has been given much more importance than the role "fictitious capital" actually plays in the accumulation, or disaccumulation, process.

Thanks for the clarification.

Thanks for the clarification. If the money-ex-nihilo-camp were only to claim that financial institutions create credit instruments, specifically like a letter of credit, that would be stating the obivous. As I understand it their claim is however that commercial banks create cash, base money.

Cooked Quote: What about that

Cooked

People often seize upon things that appear to confirm their already held views. Graeber certainly did so.

Try this thread

http://libcom.org/forums/theory/has-david-graeber-become-currency-crank-22032014?page=2#comment-536963

Here is an article describing what the B of E actually said

http://www.worldsocialism.org/spgb/socialist-standard/2010s/2014/no-1317-may-2014/cooking-books-harry-graeber-and-magic-wand

To prove an argument why not analyse the causes of a failed bank

http://www.bankofengland.co.uk/pra/Documents/publications/reports/hbos.pdf

Your comment

concerns what is called fractional reserve banking. Some "radicals" are demanding 100% reserve banking but that will mean simply banks hoarding cash. Much the same as those callin for the return to the gold standard...hardly going to rock the foundations of capitalist exploitation of wage labour and extraction of surlus-vlue

To be clear, the graph I gave

To be clear, the graph I gave is not the loan to deposit ratio that Alb speaks of.

The L/D ratio is easy to find. I think it is given by the FRED site, for each country going back decades; just google "Bank Credit to Bank Deposits for" and then the name of the country, eg for the US: https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/DDSI04USA156NWDB

In the US the L/D never even surpassed 90%, but in other countries it is above 100% (eg 180%). I seem to notice a trend in the late 1980s with a lot of countries the L/D starting to surpass 100%.

Aggregated balance sheet of

Aggregated balance sheet of euro area monetary financial institutions (MFIs), excluding the Eurosystem : July 2016: https://www.ecb.europa.eu/stats/services/escb/html/table.en.html?id=JDF_BSI_MFI_BALANCE_SHEET

Total loans do surpass total deposits a bit (17,570,598 versus 17,129,393 millions of euro).

But if you look at loans and deposits just to/of non-MFIs and excluding government, they are 10,812,606 versus 11,783,393 (though in individual countries this excess of deposits isn't always the case).

Probably these numbers in any case won't convince the ex-nihilo camp, since they say that when a bank extends a loan it gives its phantom money onto a deposit of the borrower, so it seems for the ex-nihilos that loans automatically would equal deposits.

I think we have to look into the concrete detail of clearing systems, like CHAPS to find how one bank sends its money of account to another bank, ie how does the technical/software system avoid that one bank pays another bank just with its own fake phantom money, instead of with "cash"central bank money of account.

I'm actually doubtful whether

I'm actually doubtful whether the ex-nihilo camp says that commercial banks can create central bank money, but that is in fact the only thing that I object to against their fallacy. Inter-bank payments occur through the banks' settlement accounts at the Bank of England. Why else would they demand to make it easier for 'non-bank' groups to be able to open a settlement account at the central bank;

http://positivemoney.org/2016/06/bank-of-england-uk-banks-to-lose-their-status-as-gatekeepers-to-the-payment-system/

They can create these credit

They can create these credit instruments, but I think the banks sold them to others on the market precisely to get money!!!

Cooked wrote: Also that

Cooked

There is actually 0% reserve requirement in Sweden:

[quote=wikipedia]

Canada, the UK, New Zealand, Australia and Sweden have no reserve requirements.[/quote]

In the US:

In the US prior to the crisis the reserve balances held at the Fed were hardly even a $ dozen billion: https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/WRESBAL?cid=32215

This sufficed to operate daily transactions that were greater than $ 2 trillion:

http://www.federalreserve.gov/paymentsystems/files/fedfunds_qtr.txt

---

For an inter-bank payment, a bank can obtain the necessary 'central bank money' from the central bank by selling a security to it. Clearly it is the central bank itself, not the commercial bank, which creates this money.

But the question is, whether commercial banks have free/unlimited access to the central bank's facility, ie whether the central bank could some moment refuse to accept to facilitate the commercial banks.

Or maybe, in case the central bank does not have this ability (because that would crash the system?), perhaps it does have a relative power about the conditions under which this facilitation happens, ie to increase/reduce the interest rate at which the commercial banks can borrow from it.

Perhaps the ex-nihilo camp is saying that even the central bank rate does not have the power to force commercial banks one way or another (borrow more or less)? This is probably the crux of the matter.

Noa Rodman wrote: Perhaps

Noa Rodman

I agree or phrased otherwise how it works in practice regardless of regulatory or theoretical ideas.

It's also almost a philosophical issue to determine if it's the central bank or the private bank who "created" the money in the above scenario.

It's the central bank who

It's the central bank who creates the money; it can refuse to lend ("create money") to commercial banks in distress:

Fed's Discount Window: Closed for Banks on Brink (12 April 2011)

(http://www.wsj.com/articles/SB10001424052748703518704576258993132298396 google the title for full view)

Reserves at the central bank really seem necessary only for inter-bank payments, otherwise reserves are useless. Now with QE there are excess reserves deposited at the central bank.

In a recent interview Keen said that banks cannot lend these reserves out. Curiously he also seems to fall into the logic about a necessity for 100% reserves in this case, arguing that if the bank would lend out someone else's deposit to you, and then that someone else wants to withdraw his money, Keen ask how can the bank give that money to them, since it is lend out.

His point seems though that the excess reserves of the banks stored at the central bank even just physically cannot be lend out. Well they could disappear probably if banks asked for actual paper cash. Commercial bank indeed cannot themselves destroy these excess reserves (Keen laments excess reserves, since banks lose money on them under the negative interest rate now). The way the excess reserves can be destroyed is only by the central bank itself. So if the commercial banks cannot destroy the central bank money, how can it be said that they have created it?

There is a lot of talk about

There is a lot of talk about negative interest rates by central banks (Sweden, Denmark, Switzerland, Japan, ECB https://www.theguardian.com/business/2016/feb/18/negative-interest-rates-what-you-need-to-know).

What is meant is mostly the deposit rate, not the lending rate.

And it is usually only on (some level of) excess deposits (of commercial banks held at the central bank). So in the ECB it seems excess deposists are now 541,622 million: https://www.ecb.europa.eu/mopo/implement/mr/html/index.en.html

-0.4%

would be (assuming it applies to any excess amount) about 2 billion euros that banks have to pay to the ECB, which would be handsome profit for the ECB, though I doubt it is that much (and over what period?).

It is actually a bit difficult to verify in the cases of Sweden and Switzerland whether it might be the lending rate that is negative. The Guardian piece says;

My estimate of 2 billion euro

My estimate of 2 billion euro interest payment on excess deposits over 1 year to the ECB seems accurate.

It's not clear if this money simply vanishes, or if it somehow goes to the ECB as a profit (on to its own account? - at least we don't seem to have balance sheet statistics to track this).

Steve Keen is right that the banks cannot lend out their deposit reserves (held at the central bank), in the sense that any inter-bank payment just shifts around the money from one bank's account at the central bank to another's. Except for cash withdrawal. However they also could shift the money to deposits overseas that do not charge negative deposit rate (this is called euroeuro, like eurodollar).

I see no reason why eg German banks with excess reserves at the ECB wouldn't simple move their money offshore to avoid negative rates. It's probably just difficult to track this. (same with estimating the total dollars held in overseas deposits)

Well the figures do seem

Well the figures do seem available, for instance euros in the UK, even divided by bank's nationality, so we see:

Monthly amounts outstanding of European-owned (excl. UK-owned) banks' euro deposit liabilities total (in sterling millions) not seasonally adjusted:

31 Aug 16 300368

_

So if I got it correctly, there are 300 billion euros (tho this is actually valued in sterling) deposited in the UK only by European banks.

I don't think they are subject to negative deposit rate. So why don't euro area banks simply transfer their excess reserves presently at the ECB to their UK branch/subsidiary, if the ECB deposit interest payment is so damaging to their profit as they claim it is?

You can find economists who

You can find economists who say that banks lend out reserves and rely on our deposits to make loans. And you can find those who insist that they don't and that banks create new money out of thin air. Both are true depending on how you look at it.

This article explains it very well: https://spontaneousfinance.com/2014/01/28/banks-dont-lend-out-reserves-or-do-they/

...

...

I did check that blog. The

I did check that blog.

The standpoint of the ex-nihilo camp can only be accepted under the ridiculous conditions that the loan which a bank gives to a borrower actually isn't used, but remains on deposit with it. So yeah, the deposit is created out of nothing, but since the borrower doesn't actually make use of the money, this is obviously not what most people understand when we talk about a bank loaning out money (ie it involves either withdrawal of cash by the borrower, or using the borrowed money to pay someone who is not a customer of the same bank, thus an inter-bank payment).

Even basic Trots now claim

Even basic Trots now claim that banks create money ex nihilo;

http://www.marxist.com/what-is-money-part-three.htm

Adam Booth (from IMT)

Shake my head.

Regarding the origin of fractional reserve banking though, textbook history says it was the London goldsmiths. I tried to find more info about this, but it turns out there is next to nothing. I think I read a fire destroyed any records. So I'm sceptical, as this goldsmith story seems to rest pretty much on mere speculation.

One of the earliest sources

One of the earliest sources the SPGB has found is this.

Richard Cantillon's "Essai sur la nature du Commerce en General" (it's in English) written in 1730. Here's what he wrote:

Nothing here about the goldsmith/banker being able (or even trying) to lend more than the 100,000 ounces of silver deposited with them, as in the fairy tales of the currency cranks.

Cantillon's full account of how the banks of his time operated can be found in Chapter VI at

http://evans-experientialism.freewebspace.com/cantillon03.htm

There were some goldsmith/bankers in London in the 17th century but not in every town. But the goldsmith/bankers seem to rather have been more like pawnbrokers for the idle rich.

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/History_of_money#Goldsmith_bankers

http://heritagearchives.rbs.com/wiki/Edward_Backwell,_London,_1653-82#Backwell_t\

he_banker

Adam Smith makes no mention of "goldsmith/bankers". His description of how the Bank of Amsterdam operated confirms that the currency cranks have not been able to produce any example of a bank that issued more certificates of receipts than the gold it had (and survived).

On so called "shadow

On so called "shadow banking".

This is just a stupid name for investment/merchant banking (include asset-managers like Blackrock into the category).

The Glass-Steagall act is most often invoked, arguing for the need to (again) separate deposit- from investment banking (because that supposedly gives greater stability against crises).

[quote=Hilferding]In any case, the modern trend is increasingly to combine these functions, either in a single enterprise, or else in several different institutions whose activities complement each other, and which are controlled by a single capitalist or group of capitalists.[/quote]

I question how real (in practice) the separation of deposit and investment banks was even under Glass-Steagall. Today, as the wiki entry on shadow banking points out: "Many shadow banking entities are sponsored by banks or are affiliated with banks through their subsidiaries or parent bank holding companies."

Politicians do recognise the need for this "shadow banking", eg in EU: http://www.reuters.com/article/us-eu-regulations-idUSBREA2N08U20140324

Although Deutsche Bank seems actually (being forced by the US) to withdraw from that field.

The soviet economist Zachary Atlas wrote some stuff about this in Vestnik in 1929-30.

--

On so called dark pools (a private forum for trading securities). Let me quote again Hilferding:

Hilferding

Almost every major bank has its own dark pool:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Dark_liquidity#Broker-dealer-owned_dark_pools

Perhaps I should differentiate dark pools from internalization. It might be the latter to which Hilferding is referring, but they are related.

An article from 4 years ago:

Goodbye Exchanges: Hello Internalization and Dark Pools

Executing orders on exchanges is quickly becoming a thing of the past.

About thirty three percent of U.S. trades are now being executed outside exchanges with internalization methodologies overriding dark pools, says a recent study released by New York-based consultancy Tabb Group.

Of the thirty three percent, thirteen percent was executed in dark pools and the rest was via internalization -- a practice whereby broker-dealers match orders internally on their own trading desks before sending them to either dark pools or exchanges. The thirty three percent represents more than double the fifteen percent of orders executed outside exchanges in 2008. The term "dark pool" refers to a place where trading liquidity -- a supply of shares -- is not displayed for all to see. The anonymity afforded to investors and trades through either independent or broker-operated dark pools protects not only the identities of the trading firms, but can also help mitigate market impact. That is the sensitivity of price shares to movement when any sizeable demand surfaces.

"While some traders are upset that their orders are being surreptitiously spammed around the market and others complain about fleeting quotes and inexecutable liquidity, there is a core group of traders who view higher ark execution ratges and lower commission levels as outweighing the information leakages messaging barrage," write Larry Tabb, founder of Tabb Group and research analyst Cheyenne Morgan who co-authored the report entitled "Tales from the Dark Side, Out of Sight, but Very Much in Mind."

Tabb and Morgan cite several reasons why exchanges are ending up with orders nobody wants. The obvious one -- reducing market impact. Yet others: as trading volumes decline, buy-side traders are turning to internalizers and dark pools much earlier in the trading process than in the past to find the necessary liquidity. Second, an increasing amount of order flow is being managed electronically as humans don't have the ability to track liquidity across 50 venues operating under such low latencies. As a result, managing cost is becoming critical. Matching orders internally is a lot cheaper than executing orders on exchanges.

Last but not least, technological advances are also helping dark pools and internalization engines gain popularity. Trading desks can now send out messages to solicit the other side of the trade and if an order can't be done directly it will immediately go to one of more dark pools in a fraction of a second.

Written by Chris Kentouris, Editor-in-chief at www.iss-mag.com

__

So this seems to confirm Hilferding's point of banks taking over the function of stock exchange (it would be interesting to discuss and study these questions in more detail). Questions; what percentage of stocks is traded like this, how does it work concretely, etc?

Quote: Commercial banks

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Decline_of_the_Glass%E2%80%93Steagall_Act

I found that already as early as 1957 banks were permitted to receive profit from brokerage transactions performed for the convenience of their customers, ie brokerage commissions (this is not mentioned on the wiki page).

--

Apparently no longer permitted by the IRS, but from the early 1960s to the 2000s, there existed exchange funds (or swap funds). This was only for the very rich, with the goal of diversifying stocks, while postponing tax associated with sale of stocks. They put their stocks (of one company) in the fund and in the end they got stocks of the same value but of a whole bunch of different companies. So it looks like actually the stocks were "bartered" here (though not at the own choice by the owners themselves, but by the fund operater apparently). It has only some resembles to dark pools. Exchange funds were not very well-known. Perhaps they even still exist.

Factoring.

Factoring. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Factoring_(finance)

I'm sure Hilferding also had this in mind when speaking about the dominance of banking industry over industry, though the exact term is not found in his book.

https://www.entrepreneur.com/encyclopedia/factoring

http://www.mcsmag.com/tricks-traps-avoid-factoring-companies/

--

To return to a question I asked earlier in the thread:

Noa Rodman

I'm probably mistaken that currency deposits can exist outside its central bank.

As regards the figure of euros listed as parked in the UK, I think they must in reality still always be held (in this case by a euro-branch of a UK bank) at an account within the ECB.

First I naively believed a currency deposit held outside the borders of its issuer somehow was electronically transferred abroad and resides on a foreign computer system.

^ my above interpretation

^ my above interpretation seems still wrong of this:

I now think those "deposit" liabilities are not actually euros, but euro-denominated debts.

--

The cause of my confusion is probably reading stuff about so called Eurodollars. They are always explained as if they are dollars held on deposit outside the US (ie mainly Europe, hence their name). At least, that was the impression I got.

So what is a dollar deposit held outside the US?

http://www.investopedia.com/exam-guide/cfa-level-1/derivatives/eurodollar-time-deposit-markets.asp

So they are not actually dollars. They are a dollar-denominated debt.

Governments and corporations outside the US can issue debt denominated in dollars, so it seems quite logical that banks outside the US can do this too.

But, to stress the main point of this thread, this is not "money creation".

[edited to add:]

The debate with the ex-nihilo camp is pretty much just semantics about what is money. They know of course there is a difference between a dollar and a dollar-debt, but they colloquially call them both money.

The Eurodollar-phenomenon

The Eurodollar-phenomenon also misled Robert Kurz into talking about money creation outside the central bank:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-Jz08K3bx3g (brief comment at 2h 6min)

Krise: Business as usual oder mit Volldampf in den Kollaps? Karl Held & Robert Kurz

-

In English there's a lecture series by economist Perry Mehrling, in which he correctly talks about the Eurodollar:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=dNf4V0WMbiM

Actual money deposits are always held at the central bank, they don't leave the country. Foreign commercial banks outside the country that hold deposits in its currency, actually have an account at a subsidiary or account at a correspondent bank inside the currency's home county.

But just like the total size of commercial bank deposits is greater than the size of their deposits held at the central bank, so too can foreign commercial banks "multiply" their deposit (held inside the central bank).

To speak about "multiplying" can be misleading. What happens is the same sum of money is lend out numerous times. For instance 4 times. But that doesn't mean there's 4 times as much money now. The first lender lend out the money to someone else, and so on. When payment on the first lender's loan comes due, the money must flow back through the chain (from the fourth borrower, back up through to the first lender).

The extent of this chain (or the "multiplier") is not determined by the central bank, rather it's endogenous, ie by the needs of the borrowers. If that's all the money-ex-nihilo camp wants to say (and who actually disagrees with this point), it would be fine. But perhaps in order to appear controversial/radical, their presentation gives the impression that commercial banks create (base) money out of nothing. But again, I don't think they actually claim that.

Don't wish to detract from

Don't wish to detract from the interesting more detailed discussions which Noa Rodman has kept going on this thread but for anyone looking up this thread for the first time and struggling with the basic arguments Adam has given this short (and sometimes entertaining) talk at a recent spgb summer school and also answered some common questions in the discussion section here:

www.worldsocialism.org/spgb/audio/idiots-guide-banking-how-avoid-being-currency-crank

PS:Thanks for the tip on Kurz.

I disagree with one objection

I disagree with one objection made in that SPGB talk against alleged currency cranks, namely that if all loans were repaid, then there would be no more money. I think this is actually correct. The currency (and deposits at the central bank) are liabilities, matched by assets in the form of government bonds, etc. on its balance sheet. If all those assets were repaid, ie the money would flow back to the original issuer, the central bank, there would be no currency left. One of the first assets that the Bank of England got at its foundation was a debt by the king in compensation for his confiscation of gold. I think something similar happened in the US in 1933 when the government seized the Fed's gold reserves and gave gold certificates for them. These gold certificates are an asset of the Fed, for which it can issue its banknotes.

Noa, I think you may have

Noa, I think you may have misunderstood an 'off-hand' remark about this by Adam but that's up to him to correct if so.

Spiky is right. It wasn't

Spiky is right. It wasn't really even an off-hand remark but a criticism of the stated conclusion of a currency crank leaflet I picked up at Occupy St Pauls in December 2011. The unsigned leaflet actually claimed:

It was about that not about the currency issued by the government via its central bank. This is accounted for as part of the National Debt, but if the National Debt was abolished (or all repaid) that would not mean that money would disappear, just that it would have be recorded in the government's accounts in a different way. Double-entry bookkeeping may have been something that helped capitalism develop but is also a rich source of confusion.

Hi alb, "recorded in the

Hi alb,

"recorded in the government's accounts in a different way"

What do you mean by "in a different way"? Without the existence of a central bank?

There would be a possibility for the government to directly print money, and so it would not have to issue debt (this is actually something advocated by some 'modern money' types).

But that would be a different system to what exists today, in which the central bank's loaned out currency is matched by assets (debt).

btw, a Marx quote against the notion of debt-slavery:

https://www.marxists.org/archive/marx/works/1857/grundrisse/ch14.htm

I just meant that, if there

I just meant that, if there wasn't any National Debt, the government-issued currency would have to be recorded under some other heading. Anyway, classifying it as part of the National Debt is an accounting convention arising from the fact that the currency is issued via a bank and that when banks issued their own notes (made a loan in notes) the notes were accounted for as a liability (the corresponding asset being the debt to the bank of the person given the loan in notes). The government could just as easily directly issue currency notes, as happens in some countries and as happened in Britain in WW1 with Treasury notes. But I don't think it's a difference worth getting worked up about even if this is what most currency cranks end up advocating.

If by "recorded under some

If by "recorded under some other heading" you mean that a currency would be backed by assets other than national debt (eg bills of exchange, as you refer to), than the point still stands that if those assets were repaid, there would be no more banknotes.

If you mean that the government could directly issue currency notes, than you're not talking about the system as it exists today. The difference is important.

During the suspension of the convertibility of Bank of England notes (1797-1821) James Mill explained (in a review of Thomas Smith’s Essay on the Theory of Money and Exchange, in the Edingburgh Review 1808):

"

There are two kinds of paper money, which are so remarkably different, that it is surprising any occasion should remain to point out the distinction between them; yet such confusion has prevailed on this subject, that some great errors owe their origin to the misapprehension of one for the other. Of these, one species is the paper money issued by government, and which it is rendered obligatory upon the people to receive. Of this nature were the assignats, and the mandats, issued by the revolutionary government of France; of this nature, too, was a paper money issued by the government of the United States in the crisis of revolution, and by the Dutch in their celebrated war for the independence of the republic. The second species of paper money consists in the notes of bankers, payable to bearer on demand, and which pass current for the sums there specified. Bills of exchange and other obligations, payable only at a stated time, and bearing interest, are sometimes denominated paper currency; but it will contribute to distinctness, if we exclude them from the appellation of paper money.

We are disposed to give Mr Smith very considerable praise, whether he discovered the distinction, or learned it elsewhere, for having very clearly perceived the difference between the paper money which a government may force upon the people, and the paper money circulated from banks, which nobody receives but at his pleasure.

"

Another economist writing at that time, William Huskisson in 1810 (The question concerning the depreciation of our currency stated and examined, p. 107):

“

Paper money issued in the name of the state, in aid of its own Exchequer, and in compulsory payment of its expenses, such as has been resorted to in various parts of the world, is happily unknown to this country [that is England]. Such paper is in the nature of a forced loan, which, in itself, implies a want of credit. From this circumstance alone, it falls below par ; and its first depreciation is soon accelerated by the necessity of augmenting the issues in proportion to their diminished value. Thus an excess of paper co-operates with publick mistrust, to augment its depreciation. Such was the fate of the paper issued by the American Congress in the war for their independence ; more recently of the assignats in France : and such is now the state of the paper of the Banks of Vienna and Petersburgh. Whereas, the state of our currency, in regard to its diminished value, is no other than it would be if our present circulation, being retained to the same amount, were, by some sudden spell, all changed to gold, and, by another spell, not less surprising, such part of that gold, as, by its excess, created a proportionate diminution in its value here, with reference to its value in other countries, could not by exportation, or otherwise, find its way out of our separate circulation. It is excess not relievable by exportation.

”

Marx stressed the difference:

“

Most English writers of that period confuse the circulation of bank-notes, which is determined by entirely different laws, with the circulation of value-tokens or of government bonds which are legal tender [..]

”

The point these writers are making is not that state paper money is inconvertible, whereas banknotes are convertible, because I think that’s too obvious. The point is that state paper money is expended by force, the banknotes are voluntarily borrowed (eg by selling a security to the central bank).

National debt (Treasuries) is not legal tender, it is not forced upon anyone, rather the market voluntarily buys it (with bank currency). Even plain figures make this clear, for example in the US, the national debt is many times larger than total currency. What happens is that the same note can be loaned out to the Treasury multiple times.

The Treasury does not “print currency”, its debt is not legal tender, nobody is forced to accept Treasury bonds in payment (like eg government employees, soldiers). It is also wrong to say that the currency is created “from nothing”; if anyone wants currency, they have to provide collateral (like securities).

-

Anyway, perhaps some older comrades might help me with this question:

When were the Treasury notes in Britain dematerialised (ie lose their paper-form). It's difficult to find pictures of them, since, as they are not state paper money (legal tender, forced currency) and have to be repaid, they always are withdrawn from 'circulation'.

Colloquially people do refer to national debt as money, when they speak about a central bank's foreign currency reserves. But actually these reserves are composed of foreign national debt, not actual foreign currency.

I wasn't talking about

I wasn't talking about Treasury Bills but about the Treasury Notes that were issued in Britain at the beginning of the First World Slaughter:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/HM_Treasury

Nor was I saying anything about what they were backed with or whether or not they were, merely about how they were recorded in the government's accounts.

My point about Treasury Bills

My point about Treasury Bills is that in today's system, the government does not expend them in payment for goods, it doesn't forcefully introduce them into circulation, rather people freely buy them (they credit the government).

re: the Treasury Notes from the world war, in what sense are they an example of state paper money? It is true that some view them to be such:

[quote=Bring back the Bradbury]

We require that the Treasury immediately restarts issuing such interest-free money, based upon the wealth, integrity and potential of our country. Such an initiative would completely remove the hold the banks have over the nation, and would kickstart a productive economy.[/quote]

However, the mere fact that the state carries out the printing-work of the notes is irrelevant.

Your wiki-quote states that:

So people exchanged their gold coins (sovereigns) for these treasury notes. They were smaller denominations than the existing Bank of England notes. This is a clue that they were not intended for the government's own large-scale expenditures (eg buying armaments). The assets backing the treasury notes, collected in the Currency Note Redemption Account, included government debt, gold, etc.

The question is whether that government debt had been freely raised from the public, or was issued solely/directly for the Currency Note Redemption Account. I doubt the latter.

It's the way that the notes enter circulation that matters.

Noa Rodman wrote: So people

Noa Rodman

I doubt it. Only a fool would do that. If I been around then and had some gold sovereigns I wouldn't have exchanged them for a paper note. I'd have kept them, as most people did. What happened was that the government suspended the convertibility of Bank of England notes into gold, thereby not depleting the stock they had. They wanted the gold to pay for raw materials from abroad to make armaments and shells.

More on Treasury notes and how they got into circulation (via banks) here:

http://www.rbsremembers.com/banking-in-wartime/supporting-the-nation/the-first-government-banknotes.html

There's a picture of one too. When we get socialism today's £5, £10, £20 and £50 notes can join the Treasury Bills in the museum of antiquities and antiquarians can study what money was and how the system worked.

Quote: can join the Treasury

You meant to say Treasury Notes (also called currency notes).

Obviously, not every gold coin was exchanged for a currency note. The link you posted states:

The introduction of small denomination notes had the purpose to concentrate the gold into official reserves. Germany and France did this in 1909, swelling the official gold reserves, in prospect of the impeding war.

In Britain, still in August 1915, the percentage of gold (in the Currency Note Redemption Account) backing currency notes was a predominating 61%. It's safe to assume that the origin of that gold was the domestic gold freely exchanged by the public into the currency notes, whether directly, or by natural replacement via paying stuff in gold coin and receiving income (wages) in the form of currency notes.

-

To get back to the point: How would the proposal in the OWS-pamphlet practically work? (I mean without the launching of their alternative state paper money)

The central bank should not be allowed to issue further currency. This is already enough to crash the system, but let's proceed with the scenario.

The government has to use its tax revenue for repayment of that debt held by the central bank. That the complete repayment of debt (on the central bank's asset side) would mean the disappearance of currency, can be seen today from the fact that the government's tax collection has to be offset by a monetary expansion of the central bank, in order not to disturb the inter-bank rate.

However, the government has to find a way to discriminate in repaying its debt, so that it doesn't bring money in circulation again. The priority should be to repay the central bank. In order to do that the government's account/fund (of collected taxes) has to be kept in cash (ie central bank deposits), and not, as is the case now, be temporarily invested in assets (during the time prior to government's expenditure of it). Money shortage intensifies.

In order to repay all its debts to the central bank, the government would still have to find a way to collect also the remaining physical notes. If it could overcome that detail, there would be a money-less society. There are some practical difficulties to be worked out still.

Audio of a panel on

Audio of a panel on Lapavitsas' book "Marxist Monetary Theory" at SOAS on 18 January 2017 (part 1, 3 in total online): https://soundcloud.com/soaseconomics/thinking-about-money-part-i

Quite awful, but Lapavitsas does correctly reject (in the q&a part) the view (eg articulated in an article in HM journal by a couple of authors) that new financial institutions like hedge funds etc. supposedly create money or have created a new kind of money. Often that view is also put in alarmist fashion, like, "there are $700 trillion derivatives!l!?!".

Anyone know how to respond to

Anyone know how to respond to the following conundrum:

[quote=some forum poster]Eventually, all debt, public/private exceed the economy's ability to pay it back.

All money in circulation other than coins1 is generated by a loan [let's suppose here is meant a loan from the Fed]. As loans are paid back, the money is withdrawn from circulation [...] The only way it gets back into circulation is through another loan.

Problem: the principle of the loan is injected into the money supply. The interest isn't. There is always a shortfall in the money supply to pay back the debt. Debt has to continually increase to pay back the interest. It's a dog chasing it's tail.

The only beneficiaries of our wacked out monetary system are banksters and financiers. Everyone else is saddled with perpetual, increasing private/government debt or the whole thing unravels.

When debt exceeds the economy's ability to pay it back, the party is over.[/quote]

So how does the Fed (or any central bank) make a profit (ie annual residual earnings), ie from the accrued interest on its loans etc., given that total money (backed by assets on the Fed's balance sheet) is smaller than the total income generated by these assets? In a hypothetical scenario of total repayment of the Fed's assets (as discussed above on the thread), there would not be enough money to give the Fed the accrued interest.

Annual interest-payments on

Annual interest-payments on the Fed's assets are quite possible without encountering an insufficient money supply; the accrued interest is profit, which the Fed hands over to the Treasury, who brings it back into circulation. The assets continue to exist, the notes too.

However, since the initial purchase by the Fed of the assets was at a discount, then at maturity, more money has to be paid to the Fed, than was put in circulation. I think in a hypothetical scenario where all the Fed's assets mature at once, there would indeed be the problem of insufficient money supply. But in reality the Fed's assets mature at different dates, so the Fed's profit on some matured assets is paid with money that is based on other assets that haven't matured yet. In this sense, there always has to exist some other debt (ie non-matured assets on the Fed's balance sheet). The matured assets are deleted from the balance sheet, and most of the money (the returned principal) is deleted. But the Fed's profit on matured assets is not deleted. It is again put in circulation (by the Treasury), and this happens without increasing the debt. So there is no "dog chasing its tail".

The CLS (continuous linked

The CLS (continuous linked settlement) Bank is a global settlement bank. It daily settles around $1.5 trillion (in 18 major currencies).

Daily FX trade more like $3 trillion than 5 -CLS

Leaves out double-counted and internal bank trades

Reuters

CLS Bank tries to eliminate settlement risk in the foreign currency market.

In addition to CLS’s primary purpose of mitigating settlement risk, the service has delivered liquidity and operational efficiencies for its Members, eg: Liquidity Efficiencies Through Multilateral Netting

(so from the $1.5 trillion, it comes down to perhaps "only" $15 billion to fund payment transactions daily).

Moreover it is projected to launch (in 2018) CLSNet, a standardized, automated bilateral payment netting service for FX trades that are settling outside the CLS settlement service. "In response to market demand, CLS will expand its proposed bilateral payment netting service – CLSNet – to support more than 140 currencies".

To be clear, the real final payments must still take place within the national central bank systems. Thus the CLS Bank has a direct account in those systems (eg Fedwire).

most economists -- and most

most economists -- and most economic schools -- have no notion how banks (or even a real economy) actually works. In terms of the "history" of banking, much of that are "just-so" stories.

If you take the "Austrian" school, its position on banks is driven not by an analysis of how capitalism works but rather how it should work. They need a scapegoat for the business cycle -- which their ideology assumes cannot exist under "real" capitalism -- so they look at the banks. Their basic complaint is that bankers act like capitalists (i.e., they seek to make profits by meeting consumer demand!) and this makes the interest rate no longer coincidence with its "natural" rate (an equilibrium concept which they reject in every other market!). Their conclusion is to regulate the banks to force them to have a 100% reserve (in gold!) -- which would destroy the banking system and capitalism as we (and they) know it.

But that is ideology for you...

So the notion that banks hold gold/money and loan that is a "just-so" story by classical economists who viewed interest rates as the price which equated the demand for money and savings. This is not the case.

The post-Keynesian economists are worth reading on this -- starting with Steve Keen.

I already mentioned Keen

I already mentioned Keen (linked an interview where he apparently tried to reject 100% reserve by arguing that if the bank would lend out the money of someone else's deposit to you, and then that someone else wants to withdraw money, how can the bank give that money to them, since it is still lend out to you...)

Anarcho

That notion is correct.

(btw on gold, since 2011 JP Morgan accepts it as collateral "to satisfy securities lending and repurchase obligations with counterparties")

Again, there's no single

Again, there's no single clear understanding of the claim (by post-Keynesians et al.) that banks create money out of nothing.

For example Varoufakis in a talk referred to Certificates of Deposit (CDs). So in this specific case CDs are said to be money created by banks. But if we look at a basic definition of a CD we read:

http://www.investopedia.com/video/play/certificate-deposit-cd/

So when a bank issues a CD, it does not at all create money out of nothing, but on the contrary borrows money from customers in order to use it, which otherwise would be sitting idle (in the customer's pocket). The same as with ordinary bank accounts.

someone thought CDs are money

someone thought CDs are money created by banks?

depositors deposit money in savings accounts; a CD is a larger than average savings deposit, for a fixed period under penalty of early withdrawal, in return for which predictability there is higher interest paid. the bank doesn't "issue" a CD, the depositor opens one.

seems I inexactly understood

seems I inexactly understood the remark (at min. 50) in Varoufakis' lecture, he actually said collateralized debt obligation (CDOs), not CDs. But my point stands that it is sowing confusion to equate such instruments to money:

Varoufakis

Since Noa has re-appeared

Since Noa has re-appeared elsewhere to offer some criticism of one related aspect of a recent CWO book review it's worth mentioning this more concise critical summary of various misunderstandings and errors by the likes of 'Positive Money' a good few modern capitalist economists as well:

https://www.worldsocialism.org/spgb/pamphlet/the-magic-money-myth/

You still need some patience to follow through and understand the different terminology but it's worth it.

Noa Rodman wrote: Anarcho

Noa Rodman

It really is not. I would suggest reading some post-Keynesian economic theory -- particularly the empricial evidence used to support their argument.