Through a discussion of Nike's Flyknit this essay deal with recent struggles and socioeconomic/technological trends in China, their relation to changing fashions in the West and possible forms of resistance that may emerge in global supply chains..

Note: Much of the material on China below is drawn from the important research being done by Chuang. Their blog is currently available here, and the first issue of the Chuang journal is due to be released in full early next year.

Sabot

There’s something about shoes. In the early workers’ movement, slowdowns, sit-downs and the destruction of machinery took on the name “sabotage,” from the sabot or wooden shoe. Though the frequently repeated story of workers hurling wooden shoes into turning gears appears to be a myth, the association is not insignificant. The clog was used in factories and mines as an early form of protective equipment, a sort of steel-toe boot that took on a distinctly working-class character as heavy industry proliferated across Europe. In the same timespan that the term sabotage came into usage, the sabot also became the first mass produced piece of footwear. Shedding its artisanal heritage, the wooden shoe grew to symbolize the changes sweeping the continent. It was factory-made footwear built for recently dispossessed peasants-become-workers, some of whom might, in fact, be making shoes. Altogether, it was the symbol for a complex, market-driven chain of enclosure, migration, boom and bust which, despite its complexity, really just comes down to the stupidest of logical circles: make shoes for workers to wear as they make more shoes.

Sabotage is the name for the excess of this process—its inherent tendency to short-circuit, collapse and restructure—and for the desperation of those caught within it. The act of sabotage is not a strike, nor a riot. It is something more inchoate, a blanket term covering all sorts of minor and major obstruction possible at various nodes in the production chain. It speaks to a certain immanence. Sabotage is only possible because the workers committing it are necessary. They wear the shoes, even as they make them. They need the wage to live, even as the mines and factories make for lives that are little more than a slow disemboweling. Stuck in the middle, sabotage designates a kind of desperate destruction of one’s immediate vicinity. It can be an individual act or a collective one. It is the simplest form of combat.

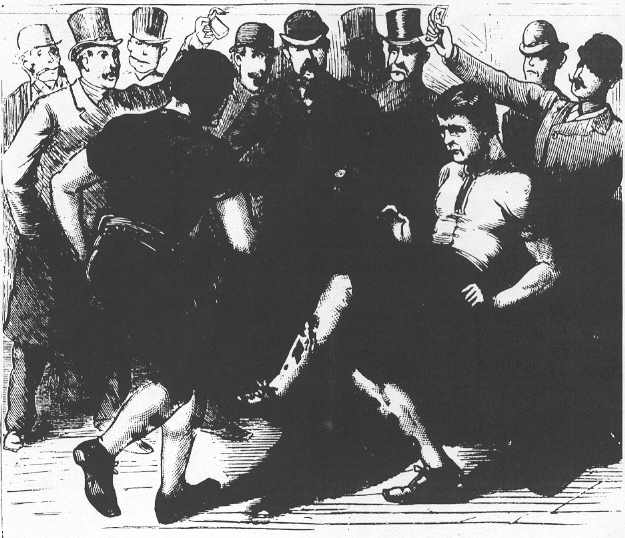

Made dependent on the wage, migrants newly dispossessed of any other means of subsistence crowded into the early industrial slums. Here, the shoe took on its martial meaning. Many of what we might call the early proletarian martial arts adapted to use the shoe as their primary weapon. Lacking the more exclusive training and arms (rapier, quarterstaff, long-sword, pole-arm) of the aristocratic martial arts, migrants packed into alleys and tenements instead fought with their workboots. In the slums of Paris, the early, street-fighting variants of what would soon be known as savate focused on open-hand blows meant to stun by striking nerves and low kicks (rarely above the groin) designed to snap the bones of the leg. In industrializing England, miners and factory workers secured hobnails and metal toecaps to their boots and engaged in bouts of “purring,” a combat sport in which competitors would fight for holds on each other’s arms and collars while hacking at the opponents’ shins with their workboots.

The industrial wasteland of overcrowded apartments and clanging machines creates desperate, alien conditions for those that live within it. There should be no surprise, then, when those who have become dependent on this wasteland seize any weapons at hand in order to strike out toward something imperceptible—a vast social system and the economic algorithm behind it—by striking at its immediate representations, including their own bodies and the bodies of other workers. In these vastly unequal, futureless hellscapes, combat offered at least the illusion of equal measure and sabotage a modicum of retribution for the bleeding away of one’s life into the machines.

Nothing

Today things have changed a little, but mostly stayed the same. Still, there’s something about shoes. Someone smashing the windows of Niketown is wearing a pair of Nikes, their white logos the only flash of contrast to the smoke-wreathed mass of young people wearing black. Later, of course, there will be screams of hypocrisy from all corners, which is really just to say from different sides of that same political center for whom “politics” is nothing but a different advertising algorithm for unique consumer profiles. But you have to admit that there’s still a certain beauty to it, just like the sabot: that sickle-shape cutting through the teargas as the fractures on the glass branch out like rivers without an ocean to spill into. It shatters and in the moment for some reason you can’t hear it because the entire thing is reverberating, our cities no longer heaving tenements but instead cop-corridors that become echo chambers the moment they’re hollowed out.

The beauty here isn’t really in the smashing, but in the ritual. The glass nearly soundless, the storefront insubstantial, populated by faceless mannequins dressed in clean sportswear while below stand their perfect, hammer-swinging counterparts. Those young people in black masks smashing at that glass as if it actually separated something when really their activity is just that: pure activity, the spectacle of burning calories dressed in black. The riot is a frenzied, liquid thing, flowing down those very boulevards cut as sluices for the easy flow of capital, all almost as immaterial as the Nike logos floating through the pale smoke, smashing at every surface as if there were something behind it when of course there isn’t, just like there is nothing, really, behind the mask.

The secret to it is simply that everyone already knows that nothing’s there in the same way that those workers snapping their shins in half and smashing factories knew that their actions wouldn’t stop the imperceptible monstrosity of their lives—but they smashed the shit anyways. Emptied of their commodities, these are only echoing corridors. There’s maybe a little bit to loot but nothing to seize—none of those magnificent machines that we all know lie somewhere, nonetheless. But not here. There is no stopping the world from here, just smashing the vicinity. The ritual, then, is best performed in Nikes.

Fly

That same year—2012, one of those years the world ended—Nike would debut two new running shoes, the Racer and the Trainer, each featuring curiously-woven, ultra-light uppers. The two models were not particularly popular with their intended demographic (professional runners) and they mostly stayed on the shelf. But behind the debut was an engineering breakthrough for the industry. Rather than being built from some combination of leather, mesh, plastic or synthetic materials, the shoes were instead machine-knit, their intricate weave crocheted by computer. The result was a complex, micro-engineered new material capable of being spun in a single piece from a line of yarn, rather than having the cookie-cutter design stamped out of leather or synthetics.

The business weeklies were the first to pick up on what was happening:

In a process Nike calls “micro-level precision engineering,” proprietary software instructs the machine to minutely alter a shoe’s stability and aesthetics. If the toe needs more stretch, the design can be digitally altered instantly to add Lycra-infused thread. For added strength in the heel, the software uses multiple layers of yarn of varying thickness. Nike plans to patent the process.

Despite the lackluster release, the new technology, dubbed “flyknit,” was rapidly scaled up. Within a few years it had dropped the functional focus and shifted to fashion. The new Kobe 9s were flyknit. Kanye was wearing them. As stylish brands like Hood by Air began to incorporate more and more haute-sportswear, the flyknits became mainstream. Combined with the fad for Crossfit, Fuel Bands and any number of performance-tracking apps, the sneakers have gradually come to symbolize a very particular urban fantasy: the fit, quantified, cardio-driven citizen, dutifully tapping workout reports into their smartphone before jogging from their sharespace office loft to the town hall meeting where they’ll offer progressive opinions on civic affairs, like a douchier version of that one Norman Rockwell painting.

The swoosh is the ultimate symbol of this mythos, the Nike demiurge. A world viewed through the swoosh is a lighter, sleeker one, if not perfect. Deindustrialization at least makes things cleaner. We’re all inventing a “new” city together and the only sin is lack of effort. At its base, then, it offers a simple promise: you can accelerate. The world moves fast but you can make yourself faster to keep up. An attractive mirage for people leaping from temp job to temp job, convincing themselves that they are self-employed “contractors” performing “immaterial labor.” The swoosh is the cardio-fueled cult of human capital.

Sometimes it comes full circle, gaining a certain post-ironic self-awareness. This is most visible in the so-called internet “microgenres,” like Vaporwave and Health Goth—not quite trends unto themselves but at least aesthetic subsets, the replacement of sub-culture with sub-reddit in an endless procession of basement-produced whatever, gaining prominence in the early 2010s. But with some of these mini-trends, what began as a simple trolling against conventions in music and fashion journalism quickly took on a weird, official character, as high-end designers like Alexander Wang released $400 pairs of track pants and the inventors of Health Goth were invited to explain the concept to Adidas executives. After a tour of the Adidas facilities, Mike Grabarek, one of the three coiners of the term commented: “There was a whole room dedicated to 3-D printers.” The epigraph to an entire ideology.

Overflow

It’s really no coincidence that these semi-aware microgenres were coined by some intermittently-employed white kids from Portland, Oregon. Long a “hub-and-spoke” regional city, Portland has in the last few decades become a deindustrialized holding zone for the whitest segments of America’s younger surplus population. Though often associated with those who suffer under the worst abjection (prisoners, slum-dwellers, refugees flooding into Europe) “surplus population” actually just designates one side of the general trend for firms to shed labor from the direct production process. As less work is needed to extract raw materials, manufacture goods and transit them to buyers, more and more labor becomes “surplus,” since it is no longer necessary for this core productive process.

One form this takes is, certainly, an increase in unemployment, imprisonment and general abjection, especially among the world’s poorest. But within the large middle-strata of developed countries, becoming surplus has more often meant the restructuring of “traditional” jobs alongside the creation of baroque hierarchies of service work, self-employment and welfare within which it is perfectly possible to lead a somewhat comfortable life. These are rich countries, after all, and the brutality of our present economic system has always been sustained as much by hand-outs as police batons.

In the United States the growth of the surplus population has manifested in the expansion of existing slums and the creation of new suburban ghettoes such as Ferguson, as well as in the creation of what we might call “green zones,” a mostly-coastal archipelago of high-employment, “revitalized” urban cores, with a spattering of rural satellites for leisure, retirement or going “back to the land.” The urban centers of Seattle, Portland, San Francisco, and New York epitomize the phenomenon, though the Twin Cities, Austin, Atlanta, DC and others tend in the same direction, while all the megacities—Houston, Chicago, LA and the greater New York complex—contain several urban cores with their own equivalents.

Meanwhile, a few cities became particularly strong magnets for more highly educated youth, who tend to settle somewhere within the service-work/self-employment segment of the surplus population, but are also attracted to cheaper housing and the “character” of a city—not out of some hipster intuition for creativity, as so many thinkpieces would have us believe, but simply because these areas tend to be where you can convert that “human capital” you’ve accumulated into a little cash to pay off all that debt or, in the worst-case scenario, re-attach yourself to the massive welfare structure of some university as a lab tech, adjunct or “grad student.” These cities are attractive because they have immense, thriving markets in bullshit—and bullshitting is one of the few skills that hasn’t yet been fully automated.

As this migrant stream spiked and Portland became Portlandia, it also became a sort of capitol for global sportswear production. In the early 1990s, just as the new factory hubs had been secured in Asia, the world’s largest sportswear conglomerates started moving their headquarters to the metro area, which today hosts the corporate offices of Nike, Adidas, Columbia Sportswear, Hi-Tec Sports, and others. These administrative hubs—part of what are called “producer services”—give their respective cities an image of post-industrial cleanliness and efficiency, generating the illusion that “immaterial” or “cognitive” labor lies at the core of the global economy. At the same time, they often serve to obscure the shadowy, logistical underlayer of the American city, itself embodied in faceless distribution warehouses, lattice-works of utility lines and container-cluttered railyards and seaports.

Today, this underlayer is obscured not through simple whitewashing but rather through its very inclusion in our fantasies of “complexity.” The flyknit is itself a perfect symbol of this fetish, its careful, computer-guided knitwork and micro-detailed colorways mirroring the inscrutable cartography of the commodity chains and high-frequency trades that shape our habitations. But this sleek imagery must also be accompanied by a robust social myth, capable of promising a new utopianism that extends beyond the spectacle. The shoe’s production is low-waste, its soles are 3D-printed, executives have even hinted that flyknit factories might soon open within the United States—an equation in which capitalism, via its own intensification, systematically solves its contradictions. The shoe crafts an image of production without the messiness of labor or environmental degradation. A process too complex for human workers, such clean production can only be handled by the tender crocheting of computers producing a technology finally adequate to the world we might hope for, in which algorithms deliver unto us shapes that emulate—even improve upon—the organicism of the world they have extinguished. This is the swoosh, reaping.

Kicks

Again, there’s something about shoes. Eugene Dennett, a member of the Communist Party in the depression years, recalls his childhood amidst the footwear factories of Lynn, Massachusetts:

I had personally seen women shoe workers attacked by mounted police, resulting in injuries, bloodshed and death. I remember my mother arming herself with two big hatpins with which to stab horses in the flanks to throw the mounted policemen to the ground. The women strikers would take a handful of cayenne pepper out of their handbags and throw it in the eyes of the downed policemen and jump on them with their “spike-heeled” shoes.[1]

This is the kind of messiness that the flyknits seek to foreclose. No more sweatshops. No more waterways poisoned for generations. Just the consumers and the machines, that swoosh lowering to cull the world of its misery.

But the reality is that smoke always rises. Beginning in the spring of 2014, Asia’s footwear industry would see one of the largest strike waves in decades. Foreboded by a spate of earlier strikes in the garment factories of the region, the unrest began in earnest with the massive 2014 strike at all six Dongguan, China facilities for Yue Yuen, one of the world’s biggest contract manufacturers[2] for footwear, itself responsible for producing a hefty 20 percent of the world’s “sports and casual-wear shoes,” including products for Adidas and Nike. With more than 40,000 workers participating, the Yue Yuen strike was one of the largest in modern Chinese history. Strikes like this soon spread from long-time contractors in places like Dongguan all the way down to newly-opened special economic zones in Vietnam and Cambodia.

The workers’ demands have mostly been about unpaid social welfare funds—benefits for things like healthcare and housing which compose a significant segment of their overall wage. But these benefits have only been called into question by rumors of factory mergers and relocation, especially in China’s coastal cities, where the past decade of labor unrest has resulted in massive wage increases. Overall, the character of this recent strike wave has been marked by minimal, defensive demands and extreme precarity, which distinguishes it from the more offensive actions following the 2010 Honda strike. As factories consolidate and relocate, either to China’s interior provinces or to less expensive labor pools in places like Cambodia, the advent of the flyknits also hints at a general downsizing. There is always a gap between the minimal demands articulated by striking workers and the larger dynamics pushing them to make demands in the first place. These defensive strikes are, then, less the simple result of unpaid social benefits and a shuffling of factories between regions and more the product of continual pressure to render labor itself redundant.

The flyknits represent the largest mechanization of the notoriously labor-intensive footwear industry in decades. According to a research report by Deutsche Bank, “the technology reduces labor costs by up to 50% and cuts material usage by up to 20%, resulting in .25% higher margins.” This has allowed for a relocation of footwear factories back up the value chain, to places like Taiwan[3] and, executives speculate, all the way back to the United States and Europe. Even this is only one part of a more generalized mechanization, which has seen Nike file patents for a fully-automated factory and invest in a separate start-up tasked solely with inventing new manufacturing techniques. And the trend is quickly being picked up by others, with Adidas already emulating the new techniques in its own line of “primeknit” sneakers. As Mark Parker, Nike’s CEO, remarked in regard to the flyknits: “The most labor-intensive part of the footwear manufacturing process is gone from the picture.”

The problem, however, is that the workers themselves fail to disappear. With its reduction of labor costs nearing fifty percent, Nike’s new production lines may require as little as half as much labor to produce the same quantity of shoes. If these technologies truly scale up, it would mean an extreme shedding of workers—at a magnitude not seen since the early mechanization of the industry. With more than four hundred thousand employees, Yue Yuen alone would lose something in excess of a hundred thousand workers, sixty thousand more than went on strike in 2014, and equivalent to almost twice the total number of employees in its six Dongguan factories.[4] Unless offset by an equally enormous influx of jobs, the result could be a wave of revolts across South China and Southeast Asia much larger than that witnessed in the past few years. The stirrings of 2014 and 2015 may simply be the beginning of the next decade’s flyknit riots.

Cull

Though Nike might epitomize the process, this tendency toward mechanization is much larger than a single company. We’re flooded with headlines explaining that, from farm work to computer science, the world is in the midst of a “second machine age,” in which workers will again be replaced en masse by machines. Anywhere from one third to forty-five percent of jobs will be automated out of existence over the next few decades, and the vast majority of these will be jobs held by the poor. This is as true for occupations in countries like the US and UK as it is for increasingly expensive, formerly-outsourced jobs in places like India and China.

The government of Guangdong province recently announced a three-year plan to subsidize the purchase of robots in order to help automate factories in the region. Several firms in Dongguan and Shenzhen have already moved to replace as many as ninety percent of their workers with machines. New printing and knitting technologies, of which Nike’s flyknits are only the most visible, guarantee the same for the apparel industry. There is even a user-friendly algorithm that will calculate the likelihood of a robot taking your job.

The trend is often met with optimism by the highly-skilled, who guarantee that the “second machine age” will create as many jobs as it eliminated, just as previous bouts of mechanization replaced farm work with manufacturing and manufacturing with services. These are often the dreams of people living within today’s Silicon bubble economies, part of the small fraction of the population actually employed in high-end services, STEM fields or, god forbid, “the arts.” Some even claim that the trend will, in and of itself, tend toward drastic reductions in the workweek and the general liberation of humanity from toil. These claims are similar to those made during previous technological watersheds, and, at their strongest, easily transform into prophesies of an imminent “post-capitalist” world just around the corner.

This is the core of what is called “accelerationism,” the belief that the internal dynamics of capitalism—and specifically the technological innovation it incentivizes—will accelerate us beyond capitalism itself. Accelerationism comes in a few forms, and this is its happier variant. Essentially, the happy accelerationist is a health goth minus the goth, envisioning a sleek future without the ambiguous, dark undertones of hyper-real dystopia—the swoosh is merely a fragment of our own bright inheritance, glimpsed from a distance. In the meantime, all we need to do is accelerate the very dynamics of automation currently underway, pairing them with social programs like universal basic income in order to soften the blow of labor redundancy and prefigure the cybernetic socialism of the future. The accelerationists at least avoid the cheap optimism of the Silicon Valley douchebag.

But the problems remain. All of these hopeful futures are, first and foremost, built on half-told histories. While it is true, for example, that the toil of farm work was in large part replaced by employment in manufacturing, the procedure was a bloody one, in which peasants had to be forced off the land and into the slaughterhouses of early-modern factories in industrial Britain. The process was also marked by high unemployment, overflowing slums and frequent crises, accompanied by the overproduction of goods newly cheapened by mechanization. A series of “Great” Depressions followed the waves of technological innovation, each greater than the last in both its promises of mechanical salvation and the depths of the misery it actually delivered as smaller and smaller shares of the labor force were employed in the new core industries. Technological progress became, simultaneously, the evisceration of employment.

Again, it is simply not the case—and it never has been—that this employment loss is magically “made up for” by new, non-productive industries developed to attend the productive ones. The excess workers are a net cost. In some cases this cost is made up for at the expense of wealthier workers, whose consumption of services pays the bill for poorer workers. In other cases the state takes up the cost in the form of welfare, stimulus spending, prisons or simply through an array of social programs mashed together in an attempt to pay the diffused costs of slow-motion societal collapse. In all these instances, this general cost takes the form of second-hand rents charged on productive work.

Short of these options, discarded workers can break back into the productive sphere by entering the illegal economy. This sort of activity may grow to include larger and larger sections of the global workforce in regions that cannot afford the other, more expensive, responses, as evidenced by illegal logging in Southeast Asia, the poppy industry in Afghanistan and, of course, the Mexican cartels. Such black market activities are facilitated by the “regular” market and help to subsidize it, often acting as the bottom-most layer in global supply chains, as in the mining of diamonds or rare earth metals in Africa. More generally, however, the illegal economy provides a sort of statistical buffer to the global market. Precisely because it is not counted in official economic data, the black market is capable of subsidizing the visible economy with invisible inputs.

In California’s emerald triangle, for example, weed money trickles down to expand employment in services, raise rents and boost tax revenue, with many residents’ disposable income seemingly appearing from nowhere in official census data. In rural China, local officials hire gangsters to clear villagers from land, which is then sold to real estate companies, used for industrial development or aggregated into new, mechanized farms owned by massive agricultural conglomerates, their on-the-book expenses cut to nearly nothing by the shady nature of the acquisition.

In the US, the extremes of this trend are evidenced by skyrocketing numbers of families living in complete economic destitution. According to the Survey of Income and Program Participation, the only survey that records individuals’ entire range of incomes, the number of households surviving on less than two US dollars a day—the World Bank’s standard for poverty in the developing world—had more than doubled between the mid-90’s and 2011, with 1.5 million households and “one out of every twenty-five families with children in America” falling into this category.[5] Here objections will inevitably be raised. Depending on one’s taste, the problem can be blamed on political shifts (Clinton’s welfare reform), corporate greed (if only we taxed the rich), moral decline (get a job), or, of course, immigration (they’re taking all the jobs)—anything but technological innovation, the one fragment of good news we have and maybe the only hope of saving ourselves from ecological catastrophe.

Unfortunately, aside from data on the massive replacement of middle-tier jobs with low-end service work, the rise of homelessness, a gap between rich and poor so extreme that it’s getting hard to put on one graph, and all the studies on mechanization linked above, we also already have an intuitive understanding of the relationship between this trend and the automation of productive work. A brief list of the 20th century’s own Silicon Valleys makes this abundantly clear: Detroit, Baltimore, Cincinnati, St. Louis. These names invoke in us a basic gut feeling—that sense of impending apocalypse, complete with images of blasted cars clogging freeways, bridges rusting over feral rivers, trees and vines reclaiming skyscrapers. It’s the feeling that makes you hoard cans in your basement, buy road maps from the gas station and ink out routes in red so that everyone in your family knows where to go when it happens, whatever it is. These cities were once what our coastal metropoles are today—economic powerhouses at the forefront of technological innovation. Now they have become little more than a foreboding of our own dark future. Because deep down we already know the truth: these landscapes are what the swoosh leaves behind when the reaping is complete.

If you cut away all the deification, demonization and just about everything else, this is what lies at the core of Marxist thought. In competition with each other, individual firms have an incentive to revolutionize production. Nike, as the company to introduce the flyknit automation, stands to benefit immensely. Even though the machines themselves are expensive, the early-adopter firms sit at a profitable juncture, able to draw all the labor-saving benefits before the technology generalizes and the market price of the commodity adapts to the new conditions. As Adidas and others begin to copy the method, however, these gains will grow sparse. The machines become an expensive necessity. Their lifetime of productivity is purchased up front, with added maintenance throughout. If a worker gets injured, killed or simply grows old, s/he can be replaced with little additional expense. The reproduction[6] and replacement costs of the worker can be externalized to the family, the church, the state, the prison, the farm, the forest, the grave. For a machine, however, every breakdown comes with its price tag. Each part must be paid in full.

Despite initial excitement, then, every technological breakthrough has a paradoxical effect. For the firm, what was once an immensely profitable investment is now a huge, fixed cost, at risk of becoming obsolete as new technologies arise to replace it. For the worker, the growing ease of production makes it more and more difficult to find and do enough work for enough money. Meanwhile, what is produced becomes increasingly opaque. The actual knowledge required to make a car, a computer, even a hunk of steel, grows more rarefied, itself an expensive commodity rationed to smaller and smaller shares of the population, often pieced apart and distributed so widely that no single engineer or programmer actually knows the entirety of the process, which can only be synthesized at the social level through coordination between many firms via the market. The process is abstracted—not in thought, but materially or “objectively,” by its literal piecing-apart and recomposition in the market, with the mechanism of money as an abstract universal equivalent. The shoe itself arcs toward the swoosh.

In his early writings, Marx described the process as one of labor’s “estrangement” from its own products:

The worker becomes all the poorer the more wealth he produces, the more his production increases in power and size. The worker becomes an ever cheaper commodity the more commodities he creates. The devaluation of the world of men is in direct proportion to the increasing value of the world of things. Labor produces not only commodities; it produces itself and the worker as a commodity – and this at the same rate at which it produces commodities in general.

This fact expresses merely that the object which labor produces – labor’s product – confronts it as something alien, as a power independent of the producer. The product of labor is labor which has been embodied in an object, which has become material: it is the objectification of labor. Labor’s realization is its objectification. Under these economic conditions this realization of labor appears as loss of realization for the workers; objectification as loss of the object and bondage to it; appropriation as estrangement, as alienation.

Each moment in this productive process becomes, then, not one instance in the fulfillment of human needs but instead a point in the metabolism of capital itself. This is what the French communist, Jacques Camatte, called the “material community of capital,” in which “there is no longer any distortion between the social and the economic movements as the latter has completely subordinated the former.” This material community is represented by the growing domination of fixed capital, which is itself “dead” labor—machines, factories, roads, ships, skyscrapers, power plants, server farms, raw materials—over variable capital or “living” labor, otherwise known as human beings.

The automation of production, circulation and just about every dimension of people’s lives entails the domination of humans by the dead, machine-like logic of accumulation. As this material community is secured, people become fundamentally shaped by and irrevocably dependent upon the mechanical, ever-growing mass of capital. This mass begins to appear more and more as an essential—almost natural—infrastructure supporting life itself, since all of our necessities are provided through it. At the same time, it takes on a mystical character, embodied in baroque financial instruments, ephemeral cultural symbols, and a multitude of new desires, hobbies and fetishes. All of this was considered by Camatte to be the “domestication” of humanity.

In short: the currently existing global economic system is built for the accumulation of value at an ever expanding scale. Technology is revolutionized for this purpose, and its potential to make life easier is always secondary to this purpose, remaining underutilized. What the flyknits represent, then, is not the astounding fulfillment of a human need for awesome kicks, but instead the monstrous machine-logic that lies at the heart of our economic system. These shoes are a symbol of that vast, ambient enemy—surrounding us not like encircling soldiers but like the body surrounds and digests swallowed food.

At first this might seem hopeless. But really it’s an obvious point. We are immanent to a system that we hope will be destroyed, its remains pieced apart and made into something better. Being within it suffocates and, yes, “domesticates” us, but it also exposes the internals of that system to a potentially hostile element. Several thousand striking workers in a single city in Southern China are capable of strangling a major lifeline in that global metabolism. The system’s own drive to replace humans with machines transforms more and more people into potential enemies. Many have been ejected from the mainlines of that metabolism, left to stagnate in places like Baltimore or Kurdistan. Others, like the Chinese shoe workers, populate its lifelines. Swoosh always meets sabot.

Swag

It’s not a purely destructive system, of course. These lifelines are, in a literal sense, the currently existing lifelines of the human species. Destroying the economy is only a reasonable endeavor if it is clear—not even to the general public, but to the people who advocate it—that this does not entail mass starvation and widespread rationing of whatever consumer durables could be wrenched from the rubble. Of course the project is a war, one that we are already in, even as everyone intuitively prepares for it to suddenly happen. But in order for this war to have any recognizable communist pole, it must, on our part, be a war against want. The most important front in such a war is not the heroism of military struggle, but instead the distinctly unromantic work of helping to break down and re-engineer what we inherit in that war, so that our species’ unprecedented efficiency in producing food, flyknits and other nice shit might actually be put to some use other than the world-fucking expansion of value. Communists have won before, succeeding in massive feats of armed combat against those fighting to preserve the world as it is. And these same communists have gone on to lose on that less romantic front in a slow series of agonizing defeats stretched across the 20th century.

The flyknits, then, also signal something brighter. They hint at the promise of this second, more fundamental war—where victory doesn’t mean living with less in the name of equitability, but instead dank footwear for everyone for free. This is Yacht Communism, the only thing worth fighting for. Against the pre-lapsarian bemoaning of the modern era—in all its many forms, from oogles to ISIS—Yacht Communism argues that everyone should just be able to have nice shit. That’s it. Fully automated luxury communism. On a technological level, it’s surprisingly reasonable. On the social level, however, it seems impossible. This is because technologies can’t really be separated from the large-scale social coordination that operates them. But the destruction of our current batshit-crazy ways of doing things doesn’t mean the liquidation of all the technologies we use to do them.

It’s a point taken too far by the accelerationists, but one that is there nonetheless: these technologies have immense potential. The productive revolutions that have marked capitalist history, beginning with its unprecedented intensification of agricultural productivity, are so efficient that they seem to almost infer a communist ends. But the global supply chains that make them work are built as much for combat as for efficiency. Piecing apart the production process across large territories is often inefficient and expensive. These costs are made up for in the ways that they weaken workers’ power to demand higher compensation for their work. Expensive redundancies are built into these networks, for example, to ensure that when strikes do happen at one link in the chain, there are back-up channels to keep production flowing downstream.

The question, then, is one of “reconfiguration.”[7] These logistical systems themselves may largely be weapons turned against us, but the technologies that they coordinate are not all guilty by association. Some can be extricated from these systems more readily than others, and discovering what can and cannot be severed from global production networks requires a process of experimentation carried out by those who have gained some knowledge of how these technologies operate. This process can only really take place in the space opened by major upheavals that involve the seizure of productive, rather than purely circulatory, territories. We call these spaces “communes,” a term that ought to be used much more sparsely than it currently is.[8] Certain potentials might be identified and debated earlier, but only in a speculative way, and speculation quickly grows incestuous. History is a cascade of bone-snapping dice. It’s hard to guess the numbers before you’re being crushed under them.

The recent strike wave among shoe workers shows the eviscerating power of logistical systems, certainly—the workers can do little more than defend benefits they might get if the factories relocate—but it also raises the specter of what might actually happen in a major shutdown. Similar events in the region’s history (in Gwangju, Korea in 1980 and Tiananmen Square in 1989) quickly grew to dangerous proportions, ending in violent repression. One reason for the extremes of this repression, which was much more brutally exacted upon workers than upon student-participants, was precisely because the presence of such productive infrastructure combined with the involvement of workers began to pose questions of power seizure and, thereby, reconfiguration, which is essentially the question of what to do with what might be seized. These were not breakaway movements in far-off rural areas rich in natural resources and poor in everything else—they could not simply be quarantined.

The threat is not just that these workers have an amplified disruptive ability because of their position in the global supply chain, but also that they hold a general knowledge of how production itself functions. In the cardio cult’s fetish for complexity, we are encouraged not to disentangle these things—they are purely complex, the work of professionals. But the fact is that the skill of making factories run is still largely devolved to workers. Yes, the intricate knowledge of design, high-level programming, supply chain coordination and specialized engineering are concentrated elsewhere, but one of the reasons that places like China and Vietnam became ideal locations for factories was precisely the high literacy rates and glut of mid-level engineers they had inherited from the socialist period.

These systems are complicated, but they are not impenetrable. As they disperse further—returning hyper-mechanized shoe factories to the United States, for example—their accessibility is also dispersed. But, again, the piecing apart of the process by logistics chains ensures that this is not an endeavor that can be taken up individually, nor locally by “communities.” This knowledge can only be synthesized collectively, and the linking up of these different pools of knowledge—for sabotage as well as counter-logistics—is the essence of communist partisanship. The myth of “complexity” must ultimately be forced apart in practice, and this force is not given but constructed. This is the distinction between communism and acceleration.[9]

Glass

The windows finally shatter in that way that shop windows are built to shatter, not in giant knife-long shards but instead in a cascade of frost, the Nikes glittering with it after. Even then, though, the conundrum remains: what is being smashed?

Riots, blockades and mass occupations in the US or Europe are primarily interventions into the circulation of commodities. Since the “logistics revolution” beginning in the 1970s, the intensification of finance, transport, warehousing and retail has become central to increasing profit, closely integrating the productive and circulatory spheres. This is frequently portrayed as a “scattering” of production across a worldwide “social factory,” and it’s often pointed out that massive-enough stoppages on the circulation side will quickly cause production to stop as well. Networked dispersion is then taken to mean that resistance, too, will disperse such that interventions at any point in the chain—whether a factory or a university—will contribute to a more general disruption of that system. If we look closely, however, it seems that these notions of “scattered” production and the “social” or “global” factory are merely that same myth of complexity, translated into academic tracts or anarchist pamphlets. The idea that all interventions somehow “matter” is, very simply, wrong.

This isn’t to say that only disruptions in the traditional factory are important, however—or even that any disruption really matters that much at the moment. Global production has various nodes, corridors and unintentional dependencies, and these all become potential chokepoints, providing an asymmetrical leverage against it. Rather than attempting to make strict divisions between what is actually productive, what merely aids in production, and what is, ultimately, just a rent charged on it, we might approach the question from this more pragmatic angle. Years ago, the authors of Nihilist Communism argued that there exists an “essential” proletariat, composed of workers who produce or distribute “things without which the economy would crumble” and who can thereby “halt vast areas of the economy by stopping their work.” This is not simply factory or shipping work, but also includes seemingly mundane things like telecommunications, garbage disposal and other public utilities.

Though Nihilist Communism might take the emphasis on these workers too far, their breakdown of priority within the industries is perfectly correct. And this is why most riots and blockades are little more than a ritual, which may have a vast social effect—capable of compounding in the future—but do not in and of themselves greatly disrupt or threaten the present economic system. Even the riots in Ferguson and Baltimore, followed by national highway blockades, present a social rather than economic threat—and the problem here is that the social threat can easily be diverted into a politics of representation. The riot becomes the “voice of the unheard” and political recuperation, then, takes the form of properly representing this voice.

Even if this representation fails and the riots continue, growing into genuine, behooded rebellions, they are only capable of seizing territories that have already been evacuated. Our cities are not collectively-produced resources to which we have any sort of “right” worth affirming. They are spaces for the flow of capital, and, if that flow stops, they are rendered into little more than hollow corridors and empty big box stores, abandoned cranes standing like ponderous skeletons over the wasteland of any “victorious” insurrection. The smashing of Niketown is, in its own way, a recognition of this. What is being smashed at in desperate futility is this “glass floor” separating production from everything else. And the smashing falls flat because there is nothing, really, to strike. The hammer swings instead into a yawning chasm—hurled into the jaws of the swoosh.

Underneath this spectacle, though, there is still the social binding that is the function of every ritual. Activity builds basic affinity. So this isn’t to say that smashing shit is useless—even the seemingly self-destructive catharsis of savate and shin-kicking had their own importance. So by all means, go get some friends, dress in black, put on some Nikes and burn down an Applebee’s[10] or something. But it’s just an Applebee’s. Aside from their therapeutic effect, these forms of minor sabotage and comforting self-destruction really only become collectively worthwhile if they are then used to make strength and coordinate inquiry into the actual structures of power that surround us. In the long-term, this means building the potential for a communist counter-logistics out of practical knowledge. Engineering, programming, agriculture (like, actual agriculture, not your shitty organic garden), construction, metallurgy and math—basically a list of things the left is currently allergic to—are all absolutely foundational. Only with actual skills, often gained through work, does the abstract knowledge of these chokepoints become relevant, since sabotage and occupation can then be paired with attempts to build territories. This knowledge also serves to temper our enthusiasm, as most of us must simply recognize that not much is happening and we are quite far from the levers of power. It is necessary, then, to make more friends.

—Phil A. Neel

[1] Dennett, Eugene V., Agitprop: The Life of an American Working-Class Radical. State University of New York Press, Albany, 1990. p.3

[2] Yue Yuen is owned by Pou Chen Corporation, headquartered in Taichung, Taiwan.

[3] Many of the flyknits are currently produced at Feng Tay Enterprises Co Ltd., in Taichung, Taiwan, the same city that hosts the headquarters of Yue Yuen’s parent company, Pou Chen. Taichung was itself once a major hub in the manufacture of footwear during the “Taiwanese Miracle,” which later departed for cheaper labor on the Chinese mainland. It is still, however, a nexus for the industry’s regional administration and design work, hosting Nike’s Asian design center.

[4] All of this is assuming an uptick in total consumption offsetting the net loss through an increase in demand as the Asian market expands, and, of course, the retention of more labor-intensive methods for certain product lines.

[5] Kathryn J. Edin & Luke Shaefer, 2$ a Day: Living on Almost Nothing in America. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, New York, 2015. p.xvii.

[6] In the Marxist sense “reproduction” of workers means not just the literal birth of new people who will be workers but also the myriad ways that workers stay alive, stay strong and stay sane in order to work.

[7] An informative debate about the question of reconfiguration can be followed in the back-and-forth between Jasper Bernes and Alberto Toscano in the following series of articles:

http://www.metamute.org/editorial/articles/logistics-and-opposition

http://endnotes.org.uk/en/jasper-bernes-logistics-counterlogistics-and-the-communist-prospect

https://viewpointmag.com/2014/09/28/lineaments-of-the-logistical-state/#fn1-3310

[8] There has been a fad over the last several years to refer to basically everything that involves people doing something even slightly outside social norms as a “commune.” In part, this is simply a revival of the Baby Boomers’ libertarian perversion of the term, and should be avoided in the same way that one should avoid interacting with anyone who calls coffee “java.” At the same time, it can be traced to the way that the works of Tiqqun/The Invisible Committee have been strip-mined for valuable buzzwords by American Tiqqunistes and assorted anarchists. Against this trend, we argue that the meaning of “commune” can only be understood in relation to production. Sorry bro, but if your scabies-infested squat is a “commune” then this website is the People’s Republic of Get a Job.

[9] For a much more abstract take on this debate, see Ray Brassier’s “Wandering Abstraction,” in Mute magazine, alongside Anna O’Lory’s response:

http://www.metamute.org/editorial/articles/wandering-abstraction

http://www.metamute.org/editorial/articles/keepsakes-response-to-ray-brassier

[10] We hear that this is not only entirely legal, but, in fact, encouraged.

This article was originally published on Ultra.

Comments

Quote: In industrializing

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=WdO3S4IhnC0

https://www.newtechytips.com

https://www.newtechytips.com

https://www.newtechytips.com/

https://www.newtechytips.com/whatsapp-dp-images/

https://www.newtechytips.com/good-morning-images-hd/

https://www.newtechytips.com/good-morning-images-marathi/