A short history of the massacre in Puerto Rico of peaceful demonstrators calling for the release of imprisoned separatist leader Pedro Campos by police acting on the orders of the US-appointed governor.

The Ponce massacre, 1937

“Wanton killing of innocent civilians is terrorism.”

– Noam Chomsky

In 1934, Pedro Albizu Campos led an island-wide agricultural strike which paralyzed the US sugar corporations and won a great victory for the sugar cane workers, by raising their wages from 45 cents to $1.75 per 12-hour day.

From that moment on, Albizu was a marked man. Arson and bomb threats were made against his home. FBI agents tapped his phone, read his mail, and followed him all over the island. In 1936 he was arrested and imprisoned for “advocating the overthrow of the US government.”

On March 21, 1937, in his hometown of Ponce, a peaceful march was organized on behalf of Albizu Campos.

It was Palm Sunday. Men, women and children arrived from all over the island, dressed in their Sunday finest, waving palm fronds at each other. A five-piece band started playing La Borinqueña (the Puerto Rican national anthem) as the peaceful march began.

And then a shot rang out.

Iván Rodriguez Figueras fell like a rag doll.

A second shot exploded and an 18-year old poking his head out a window, fell down dead.

A third shot dropped Obdulio Rosario, carrying a palm leaf crucifix.

Everyone tried to run in all directions – but they couldn’t escape because two hundred policemen with Tommy guns and rifles were stationed all around them. They blocked every escape route, and created a killing zone. Then they started firing.

A boy was shot on a bicycle.

A father tried to shield his dying son, and was shot in the back.

An old man flew upward, his body split almost in two.

The police fired for over ten minutes. They shot into several corpses. They fired over the corpses, as if they didn’t exist…

They chased people down the side streets, shooting and clubbing anyone they could find.

They clubbed a man to death on his own doorstep.

They clubbed 53-year old Maria Hernandez del Rosario on the head so hard, that her gray matter spilled out onto the street and people kept slipping on it.

They shot a 7-year old girl in the back, as she ran to a nearby church.

They shot a man on his way home, as he yelled “I’m a National Guardsman.”

They shot men, women and children in the back, as they were trying to run away.

The bullets flew everywhere.

A Cadet of the Republic, Bolivar Márquez Telechea, dragged himself to a wall. Just before dying, with his own blood, he managed to write “Long live the Republic, Down with the Murderers,” and signed it with three crucifixes.

A few moments later, Bolivar Márquez Telechea stopped moving forever.

The police shot for thirteen minutes. By the time they finished seventeen men, one woman and a 7-year old girl were dead, dozens were maimed for life, and over two hundred more were gravely wounded – moaning, crawling, bleeding, begging for mercy in the street.

The air seethed with gun smoke, as everyone moved in a fog of disbelief. The policemen swaggered about. Blood covered the entire scene. When the smoke finally cleared over Aurora and Marina streets, the following lay dead:

- Ivan G. Rodriguez Figueras

- Juan Torres Gregory

- Conrado Rivera Lopez

- Georgina Maldonado (7-year-old girl)

- Jenaro Rodriguez Mendez

- Luis Jimenez Morales

- Juan Delgado Cotal Nieves

- Juan Santos Ortiz

- Ulpiano Perea

- Ceferino Loyola Pérez (insular police)

- Eusebio Sánchez Pérez (insular police)

- Juan Antonio Pietrantoni

- Juan Reyes Rivera

- Pedro Juan Rodriguez Rivera

- Obdulio Rosario

- Maria Hernandez del Rosario

- Bolivar Márquez Telechea

- Ramon Ortiz Toro

- Teodoro Velez Torres

THE COVER-UP

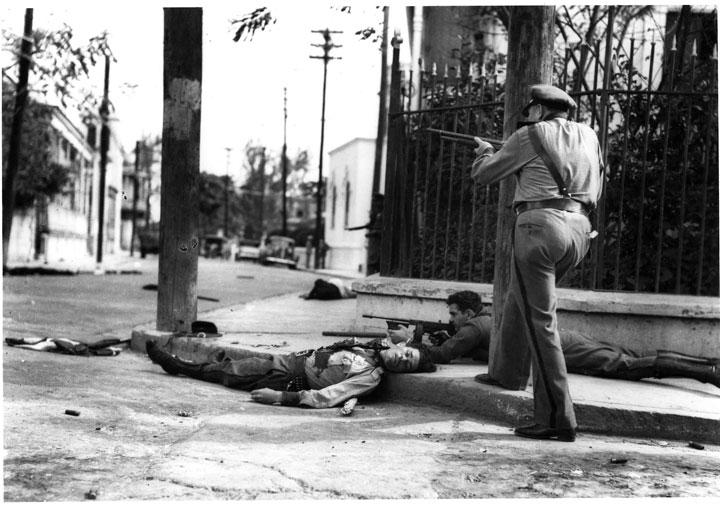

When there was no one left to shoot, the Police Chief did some quick thinking. He noticed that a cameraman from El Mundo, Ángel Lebrón Robles, was running all over the street photographing everything. He also noticed a police officer, Eusebio Sánchez Pérez, who had been killed by their own machine gunfire. Orbeta called over the El Mundo photographer, plus several of his men, and staged a series of “live action” photos to show that the police were ”returning fire” from Nationalists who were, at this point, lying dead in the street.

The first photo showed the dead officer Sánchez Pérez.

The next photo showed two officers “exchanging fire” with no one. There’s no one left in the street, a dead body lies about twenty feet away, and right in front of them lay a ghoulish prop – the corpse of dead officer Sánchez Pérez (again).

Police “exchange fire” with no one, with Pérez as a prop.

In the next photo, the Chief of Police and two men scan the rooftops for “Nationalist snipers.” Everyone is neatly arranged yet again, around the corpse of Officer Eusebio Sánchez Pérez – to suggest that Nationalists were “shooting down” at the police, who were only engaged in “self defense.”

Police “search for snipers” on the rooftops.

The transparent ruse did not work. Every island newspaper reported that there was no one to “exchange fire” with. Six days after the massacre, Florete magazine ran an illustration by popular cartoonist Manuel de Catalán.

It was an exact re-creation of the staged photo with the Police Chief and his two hapless policemen: staring up at the rooftops, looking for non-existent snipers, while the photographer says “cheese.” Under the cartoon, the caption read: “Ahora podemos decír que nos dispararon desde las azoteas.” (Now we can say that they fired at us from the rooftops).

A doctor from a local hospital, José A. Gándara, testified that many of the wounded he’d seen – including women and children – had been shot in the back. Ever island newspaper, especially El Imparcial and El Mundo, ran photos of the scene: showing walls and buildings pockmarked from all the machine gun fire.

Their front pages screamed about the Ponce Massacre, and repeated the words of Bolivar Márquez Telechea, which had been written in his own blood.

In the towns of Ponce and Mayagüez, over 20,000 mourners attended the funeral ceremonies for the victims.

An independent commission reviewed all the evidence and photographs. Over 30,000 people swarmed into San Juan’s Plaza Baldorioty, and the University of Puerto Rico campus in Rio Piedras, to hear the commission findings.

After a ten-day investigation they determined that the Palm Sunday shootings were not a “riot” by Puerto Ricans, but a police massacre.

To this day, the Ponce Massacre stands as a monument of official brutality: a terrorist act by the government itself.

It was a message from the U.S. to the people of Puerto Rico.

It was a state-sponsored slaughter of unarmed men, women and children, for the purpose of frightening them into total submission.

It was murder in broad daylight, on Palm Sunday.

Taken from http://waragainstallpuertoricans.com/the-ponce-massacre/

Comments

May be just a myth, but I am

May be just a myth, but I am supposedly related to one of the injured or killed in the Ponce Massacre.

Juan Conatz wrote: May be

Juan Conatz

Interesting. If it was one of those killed it shouldn't be too hard to find out as it wasn't very long ago. Injured would probably be trickier as there will not be a record of all of them (but seeing as the number of injuries was so high it doesn't seem that unlikely)