Steven Johns' detailed account of how Unison has handled the 2011-12 dispute over pensions. It sheds light on the role unions play in contemporary society, and argues that if ever us workers are going to start winning things again, we will have to go beyond them.

Introduction

To some people, especially young people, pensions might seem like a boring subject, however this article is not really about pensions. It is about how our conditions have been attacked and how we as workers have been fighting back against austerity, and about how the unions have acted.

I am a local government worker, and a lay representative in Unison, the UK's largest public sector union. I am writing this article for anyone who is interested in fighting austerity, defending working class living standards or perhaps even building a new type of society. In the hopes that we can learn from our experiences and past defeats so that we do not repeat them.

The vast majority of Unison members are in local government and the National Health Service (NHS) so I will be focusing on the disputes over the local government pension scheme (LGPS) and NHS pension scheme in this article. However, most of the key elements in dispute are common to all public sector pension schemes.

Background

The primary backdrop of the dispute is austerity which has been required by the global financial markets in the wake of the 2008 near meltdown of the global financial system and the subsequent recession (or depression).

In 2011, after the defeat of the student movement against the abolition of the Education Maintenance Allowance (EMA) and the tripling of university tuition fees, public sector pensions emerged as the biggest issue in the struggle against austerity.

In large part this is a result of the realities of UK anti-strike legislation, which forbids unions from taking industrial action around anything other than their own members' terms and conditions. What this means is that it would be against the law for trade unions to strike together against austerity or government policies as a whole, or even against pay,1 service or job cuts.

As the government decided to cut all public sector pensions at the same time - importantly, excluding the police, judges and the armed forces - the only issue around which it was possible for public sector unions to take joint strike action was pensions.

From my personal point of view, and in discussions with co-workers and friends who also ended up joining the strikes, the biggest issue for us was not pensions, it was the austerity programme as a whole, including cuts to vital services and cuts in benefits, all the while giving tax breaks to corporations and the rich. I believe this is probably the case for the majority of public sector workers as well.2

A big problem with the whole dispute was that this enabled it to be portrayed by the government and the media not as part of a general working class struggle against austerity but as of a "privileged" minority of the working class struggling to maintain their "privilege" at the expense of workers in the private sector.3 With some small exceptions, the unions in general - and Unison in particular - did very little to challenge this.4

Putting this to one side, I will now give a detailed account of the course of the dispute.

Chronology

As some of the events are quite complex, here is a short timeline of the dispute with the key dates:

- 9 March 2011: Labour Lord Hutton's report recommends widespread cuts to public sector pensions.

- 23 March 2011: Conservative-LibDem coalition government announces in its budget that it will follow the recommendations of the Hutton report and start cutting pensions from April 2012.

- 21 June 2011: Unison leader Dave Prentis states that Unison will strike to defend pensions, and that members should prepare for "the fight of our lives".

- 30 June 2011: Up to 750,000 teachers and civil servants strike for 24 hours against the cuts. Unison does not.

- 17 October 2011: Unison begins ballot for "sustained industrial action" across most of its membership: 1.1 million people, the largest ballot in UK history.

- 2 November 2011: Government claims to offer minor concessions including limited protection for those close to retirement which it says it may withdraw if strike action goes ahead.5

- 3 November 2011: Unison announces that 78% of members backed sustained strike action against cuts on a 29% turnout.6

- 30 November 2011: Up to 3,000,000 public sector workers in around 30 unions, including Unison, hold one-day strike.

- 8 December 2011: Government makes "new" NHS scheme offer no better than the original offer.7

- 20 December 2011: 22 Unions reach "heads of agreement" with around 20 of the unions, including Unison which the government claims "deliver the government's key objectives in full, and do so with no new money".8

- 11 April 2012: Unison ballot on the new NHS scheme opens.

- 27 April 2012: Unison ballot on the new NHS scheme closes.

- 30 April 2012: NHS workers get their first pay packets reduced by the new pension scheme.

- 30 April 2012: Unison NHS ballot result announced: 50.4% vote no, 49.5 accept on a 14.8% turnout.

- 31 May 2012: New local government pensions offer announced.

- 31 July 2012: Unison LGPS ballot opens, with the union recommending a yes vote.

- 24 August 2012: Unison LGPS ballot result announced: 90.2% vote to accept the deal.

Scope of the dispute

As a bit of background, out of a population of 60 million and a workforce of just under 30 million, there are 7 million public sector workers, out of whom 6 million are recipients of public sector pensions with 20 million dependents in total.

So this was an attack on a large proportion of the working class in the UK. Some recipients of public sector pensions work in the private or voluntary sectors whose employers are "admitted bodies" to public sector schemes. These are mostly public sector workers who have been privatised.

Now, I don't intend to go into detail about what public sector pensions were like already or why I think it is in people's interests to oppose the changes. This has already been done in articles such as this one. But in general terms the proposed changes were aiming to save the government £4 billion per year by increasing workers' contributions costs toward their pensions by 50%, and reducing the value of the pension which would be paid out when workers retire. (Meanwhile, the government continues to subsidise the pensions of the rich to the tune of £10 billion per year.9 )

The key changes

Here are the main ways the government was planning to reduce workers' pensions, following the recommendations of the Hutton report:

- Increase workers' contribution rates toward their pensions from an average of around 6% of their salary to an average of around 9% (i.e. a 50% increase).

- Increase the retirement age from 65 for most people up to 68, and for younger people instead of a set retirement age there would be a figure which goes up automatically with life expectancy, which could be up to 80 by the time children today reach retirement age.10 .

- Change the uprating (the amount pensions increase each year after you retire) of pensions from the RPI measure of inflation which includes housing costs to CPI which doesn't, and which consequently is a lower measure of inflation. At a stroke this wipes about 15% off the total value of most people's pensions.11

- Change from final salary pension schemes to career average schemes. While not inherently unfair in itself, the main problem with this is how the average is calculated over time as inflation reduces the value of wages in the past. The government will uprate past salaries based on CPI inflation -which historically has been consistently lower than actual pay rises, so over time this will devalue past contributions.

- Cut the accrual rate at which pensions build. Previously, workers earned 1/60th of their final salary every year they contribute to the pension scheme. It was mooted this be cut to 1/100 or even 1/120th per year.

- End pension protection for public sector workers outsourced to the private or voluntary sectors.

Now, while these were the main proposed changes, from a bargaining point of view it is clear that the government would not spell out exactly what it wanted to achieve with its initial proposal.

What it would do is present a particularly bad first offer, leaving some room to manoeuvre so that it could finally settle on a slightly less worse deal with the unions, which was actually what they wanted all along.

How the dispute unfolded

The Hutton report and the budget laying out how the pension cuts would be applied came out in March 2011. Contribution increases would start kicking in from April 2012, when workers would begin to see chunks taken out of their pay cheques.

Most of the other cuts would also come in immediately, like the RPI-CPI switch, with some others like the increase in retirement age phased-in over a period of time.

The unions slammed the proposals, and started talking tough about fighting them. On 21 June 2011, Unison general secretary Dave Prentis gave fiery speech claiming:

We will strike to defend our pensions, and it will be a campaign of strike action without precedent… Strike action will need to be sustained… This is… the fight of our lives12

But as we saw, this rhetoric did not match with the reality.

June 30 (non-) strike

A few of the smaller unions like the teachers' unions ATL and NUT and civil servants' union PCS, balloted for strike action over the changes very rapidly. The unions which balloted for strike action got around 80-90% of members voting in favour, and soon the date of June 30 was set as the first joint day of action.

Unison, by far the biggest union in the public sector with 1.3 million members, did not join the action . Around that time, the rumour in senior union circles was that Unison was trying to strike a deal to get a slight improvement for local government workers at the expense of some of the slightly better paid workers in the civil service and teachers etc. In fact, it was strongly rumoured that such a deal had been informally struck, as I reported in July:

Steven.

Word on the street in UNISON is that a stitch up is imminent.

Apparently the government is due to announce on Tuesday that "constructive negotiations" are going to happen around the local government pension scheme (LGPS), and that members of the LGPS will be exempted from the contribution increase.

Basically this will mean that Council workers will be exempted from the increase (effectively a 3% pay cut roughly), and that smaller groups of workers like civil servants and teachers will now be split off from the big joint negotiations, leaving them more isolated (like the pay disputes of 2007/8).

This isn't good news for council workers either, however, as it looks like the union will totally cave over raising the retirement age, abolition of protection for privatised workers, the switch from RPI the CPI and possibly the replacement of final salary with career average scheme.

Also, of course if the government now defeats the remaining smaller groups of workers and succeeds in pushing through the contribution increase, then a couple of years down the line they will do that to us as well, and those other groups of workers won't support us, as they will already be paying the higher rate.

Anyway, this is what is rumoured so let's see how things progress13

As it happened, this was not announced in July and Unison did end up balloting its members in health and local government in mid October. But I will return to this rumour as it is largely what did happen in the end.

November 30 strike

When Unison did eventually ballot for action in late October, importantly the ballot was for "sustained strike action": i.e. not just one day of action. This is key, because despite the large yes vote (78% on a 29% turnout, which is good by Unison standards), sustained strike action did not happen. Only a one off, one day strike did on November 30.

During the ballot the union did officially campaign for a yes vote - but then by this late stage feeling in the union was overwhelmingly in favour of action anyway.

In the letter which accompanied the vote, we were told we should vote 'yes' as our pension was being cut in the following main ways, which I will give in the order in which the letter mentions them: that contributions will go up, that the retirement age will increase and that uprating will be switched from RPI to CPI. I will refer back to this letter when I look at the letter which accompanied the final ballot on whether local government workers accepted the new pensions proposal.

As further evidence of the strength of feeling in favour of strike action across both local government and the NHS was that Unison recruited around 130,000 new members in the run-up to the November 30 strike. Often the union leadership claims it does not want to organise industrial action because it feels that it won't be supported by the membership. However I believe these figures illustrate the depth of feeling in this case.

In terms of the mood on the ground amongst workers, it was positive and optimistic. We had had months of escalating resistance to the austerity programme. First the student movement was causing havoc with walkouts and wildcat demonstrations. Then we had half a million people on the streets on March 26, 2011, with widespread property destruction and occupations following it.

Next was the June 30 strike of three quarters of a million workers which shut schools and public services and caused widespread disruption. Then the August riots swept the country -which even if people did not think they were particularly political, they added to the atmosphere of instability and generalised rebellion. And shortly after was November 30 - the biggest strike in a generation, with up to 3,000,000 downing tools, many of them for the first time ever - particularly in the health service.

Anecdotally, the turnouts on strike were the highest they had been in decades - at my workplace and those of people I spoke to afterwards. In my council, the stoppage was much better observed than our previous strike over pay in 2008. Something which put people off in 2008 was that local government workers striking alone wouldn't achieve much: we would have to strike with the whole public sector to start to win. And on November 30 this really was the case.

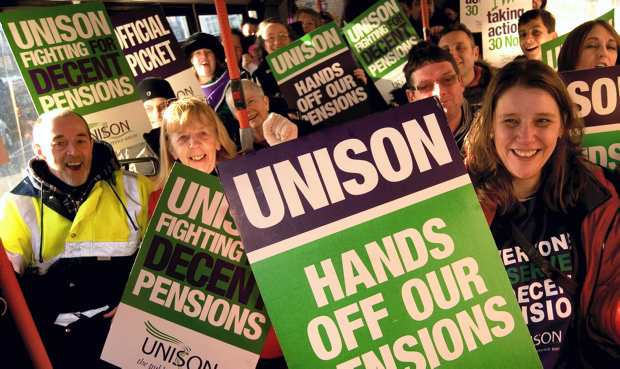

Strikers in Stockport on November 30

As well as the walkout, there were around 1000 demonstrations across the UK as strikers took to the streets in huge numbers, joining workers in different sectors together and causing more disruption.

From my workplace, pickets met up and joined with striking university workers, school staff and a mass picket outside a local ambulance depot, as well as transport workers on their day off and other supporters, before joining the mass central London demonstration.

And despite a vicious media campaign against the strikers, still we had the support of the majority of the population, with 61% overall, including interestingly 80% of young people, believing that we were justified in taking strike action.. 14

It was a genuinely exciting experience, which invigorated workers on the ground, made us feel like we were fighting back together and starting to win. And if we could win this struggle, we would start to ask ourselves what else could we win?

Snatching defeat from the jaws of victory

The union leaders declared the day a huge success, with Dave Prentis describing it as "magnificent" and telling strikers:

Be proud of what you have done today. The day you made your stand, the day you made a difference, the day you all made history and I am sure that one day we’ll look back and say today was the day we turned the tide.15

However, just a couple of weeks later on December 20, 2011, Unison along with around 20 other unions signed up to "heads of agreement" with the government on pensions which were largely unchanged from 2 November: before the strike, with the government stating that the agreements "all deliver[ed] on the approach set out in Lord Hutton’s report" and that "in all cases the enhanced cost ceilings set on 2 November 2011 remain unchanged and no additional money has been made available".16 By signing the heads of agreement these unions agreed not to organise any further action.

However, that said there did seem to be one concession on the original proposals, which is that there was a commitment to try to avoid any contribution increase in the LGPS. But as explained above, this was rumoured to have been offered already by July.

I should point out here that around 10 of the unions did not sign the heads of agreement, including most of the teaching unions, lecturers' union UCU and the PCS. Their dispute over pensions continues.

Following the signing of the heads of agreement, workers on the ground heard very little more about the pensions dispute. As the months went by, with localised cuts, redundancies, privatisations and the pay freeze continuing relentlessly, any mood for a fight or any sense of collective power dissipated.

NHS scheme

When the final offer on NHS pensions was put to members by Unison in April 2012, it was no better than that which Unison had instructed members to go on strike against the previous year. There was a slight cosmetic change in that for just one year contributions for the slightly lower paid would not be increased, to be paid for by higher contributions for those earning slightly more (over £26,557).

Here is what one NHS worker, Mark from Sheffield, told me about Unison's handling of the dispute:

Following the N30 strike Unison did nothing to support health workers, claiming that the deal after Christmas was the best deal we would get even though it was no different than the deal we went on strike for back in November. Even the local branch followed the national line.

When I asked why they weren't pushing for further strike action I was told the local mayoral elections were more important and that would be their focus. The leaflet that was produced for the ballot back in April suggested health workers should vote for the agreement. This has further added to the demoralisation of health workers who are already facing massive attacks to jobs and services and only this week [August 2012] we found out the local trust are attacking flexible workforce pay as well as reducing staffing levels.

Unison rushed the ballot through, holding it between 11 and 27 April 2012. The ballot did not contain an official recommendation from the union, although it stated that the offer was the best which could be achieved through negotiation, and that the only chance of achieving a better offer would take "sustained strike action".

Also, informational materials sent to members did not mention a single negative aspect of the new scheme, it only mentioned the neutral elements, including the final salary link being maintained until 2015, the one-year contribution freeze for the lower paid, that contributions so far would be protected and that those within 10 years of retirement would be protected.17

Unashamedly the ballot was timed to end just a couple of days before NHS workers received their first paycheques reduced by their new, increased contribution rates, at the end of April.

Despite this cynical manoeuvring by the union to try to engineer a vote in favour of the proposals, a majority of Unison members in the NHS still voted no. But it was by a very narrow margin - and the low turnout was a testament to the almost total demobilisation of the workforce by this point. 50.4% voted to reject the deal, with 49.5% to accept on a 14.8% turnout.18

Despite this rejection, Unison stated that there was "no mandate to take further industrial action". Now, while this may well have been correct by this point, this state of affairs was engineered by Unison.

LGPS

In local government we are a bit more militant and strike prone than in the NHS. We took national, all-out strike action recently over pay in 2008 and pensions in 2006. So for us the pattern was pretty much the same as the NHS, but the process was strung out for a few more months - possibly because our mood for a fight wouldn't dry up as quickly as our health worker colleagues.

So we got to see the new deal imposed on health workers, and eight months after November 30, hearing hardly anything about pensions, we were balloted on our offer, which was formally announced on 31 May. I heard through the grapevine that the proposal had been informally put together by the government and the unions months before but it was being sat on. Whether this is true or not is neither here nor there; the end result was the same.

In our final offer there was one admittedly good concession - which was that we would have no contribution increases. This was the issue which most people were most concerned about, as it would affect our take-home pay now, as opposed to our pension in the future which many people found very abstract, and impossible to calculate in financial terms as there are so many variables.

That said, it was rumoured that this had been informally offered back in July, which seems to be supported by the government stating that the heads of agreement signed in December 2011 had no new money than that which was already on the table on November 2. Although it could well be that they said that in order to save face and not appear weak, and not admit that it was a concession won by strike action.

Also of course contribution increases wouldn't even necessarily be a problem as long as pay increased enough to cover them. And Unison has not balloted for action over the pay freeze since it came into effect in 2009.

We were eventually balloted from July 31, 2012, and Unison campaigned very hard for a 'yes' vote - arguably even harder than they campaigned for a 'yes' vote in the initial strike ballot. As well as letters, e-mails and articles in the Unison magazine, they also sent two text messages to members urging us to vote 'yes' (whereas I believe they only sent one urging us to vote 'yes' in the strike ballot).

Despite this, some Unison branches continued to campaign for a rejection of the deal, which still amounted to a massive cut in our conditions. So in response to this Unison nationally sent out repeated edicts claiming that campaigning for a 'no' vote went against union rules:

Branches should promote their Service Group’s recommendation.

Branches in those Service Groups should also be campaigning for a ‘yes’ vote , in line with their Service Group’s recommendation. UNISON’s ‘Code of Good Branch Practice’ (4.4) makes this very clear. It says:

‘Once UNISON policy is determined, there is an obligation on all constituent parts of the union to work to achieve its objectives by campaigning and promoting the policy’. 19

Here is what I wrote in a previous article about these e-mails:

what makes this particularly perverse is that rule 4.4 which is cited here was actually brought in to stop individual branches campaigning against industrial action when it had already been voted on by the membership.

Here its original intention has been flipped on its head by the union, who are now using it to stop union members and activists campaigning for further industrial action to protect our conditions.

Despite this, some branches continued to defy the national union. Which then provoked Unison to take even more Machiavellian measures: instructing paid organisers to spy on branches, attend branch meetings and gather lists of names of individual union activists who voted against Unison's recommendations. This only came to light when libcom was sent a leaked e-mail originally sent by a senior Unison official.

On top of this, the propaganda sent to members before the vote and the letter which accompanied the voting form grossly distorted the facts of the deal: basically presenting the new deal as an improvement on the existing one. While you may think this is completely outrageous, this is exactly what Unison did to secure a 'yes' vote on cuts to our pensions back in 2006.

Earlier I outlined the pension reductions which the letter advising us to vote 'yes' to strike action highlighted. These were, in order: the contribution increase, the retirement age going up and the RPI-CPI switch.

The letter we got alongside the final ballot on whether or not we accepted the pensions deal, which I attach as a PDF below, first said "Vote YES" in big letters at the top. Then it goes on to simply say:

We believe that we have negotiated proposals which will mean that many members do better and pay less now and have protected the LGPS for the future

The letter continues:

Among the improvements to the LGPS negotiated by Unison are:

…

- A "career average" scheme… increased in line with… CPI

- An improved 1/49th accrual rate which means your pension builds up faster each year20

I will address some of these claims shortly. But the key thing is they did not mention a single thing which was actually being cut, including importantly the increase in retirement age and the RPI-CPI switch which were the second and third biggest reasons the union told us to go on strike in the first place. It only talked about so-called "improvements". And I will address the veracity of these now.

Moving from a final salary to a career average scheme is not an "improvement", it is a cut. Especially as salaries in the past will be uprated by CPI.

The accrual rate increasing to 1/49th would be an actual increase in financial terms if it were still talking about a final salary pension scheme. But of course it is not, it is about a career average scheme. Pension experts estimate that for a career average scheme to be comparable to a final salary scheme in terms of payout the accrual rate would need to be 1/42nd per year.

Here Unison was clearly manipulating the facts, taking advantage of the fact that most members would a: trust them and b: lack the specialist knowledge or mathematical ability to accurately assess them.

It is true that some actual improvements were achieved, including contribution rates being payable based on actual earnings rather than full-time equivalents (meaning some part-time workers could see their contribution rate fall), and that workers who are outsourced to the private or voluntary sectors will have the right to remain in the LGPS. (Although this latter concession could well be undermined with the government's planned attack on TUPE21 regulations, which provide some protections for outsourced workers.) However, this does not mean that Unison's publicity to members was not still grossly misleading. Also of course if we did achieve some concessions following one-day strike action, why did we not take the further action which we voted for in order to secure more concessions?

As with the NHS members' ballot, the LGPS ballot stated that if members want to reject the proposals, the union believed that "further, sustained industrial action" would be required "to gain any improvements, which could not be guaranteed."

Unfortunately the combination of the union's recommendation to accept, the misleading publicity materials, the manoeuvrings of the national union against dissent and the almost complete demobilisation of the membership following eight months of complete inactivity meant that, similar to in 2006, 90.2% of members voted to accept the deal. Interestingly, Unison refused to publish the turnout of the vote, which I imagine means it was embarrassingly low.

Was there another way?

Some people may believe that I am being unfair on Unison, and that the union did the best it could to fight for its members in difficult circumstances. But I believe I have demonstrated that it deliberately sabotaged our struggle in several areas. Predominately by signing up to the heads of agreement which just a few weeks earlier it had advised us to go on strike against.

If instead of immediately signing the heads of agreement and stating there would not be any further action, the union had done what it promised to do and what members voted for it to do - organise a sustained campaign of industrial action - then it would have been a very different story.

If the union was ever serious about winning, there should have been a series of escalating strikes planned, beginning on November 30. That this did not happen shows that Unison was never serious about actually preventing the attack on our conditions.

In fact, what transpired is pretty much exactly what I predicted in April 2011:

What [I think is] likely is that a one-day strike will happen, or maybe a couple, then future dates will be called off pending months of negotiations. Then a cosmetically slightly better deal will be offered, which is still a massive cut from what we have now, which the unions will then recommend to members who have now been demoralised by months of inactivity and will now probably accept. Then the unions declare victory. (This is also what happened in the 2006 local government pensions dispute)22

Why did Unison act like that?

Ultimately, I believe that Unison acted the way they did due to the structural role the unions play in contemporary capitalist society.

Trade unions have two main facets. On the one hand they are organisations of workers who have combined to advance their interests. Some have described this as the "associational function" of unions. On the other hand, they are the official representatives of workers to employers within a capitalist economy. This can be described as their "representational function".

Workers on the ground fulfil the associational function of unions by organising themselves and each other. So in this dispute this meant that tens or hundreds of thousands of workers, union activists and union lay reps did huge amounts of work talking to colleagues, organising workplace meetings, writing and distributing leaflets about the cuts. And then went about trying to build support amongst colleagues for industrial action.

To fulfil its representational function, a union needs to be listened to by the employer - in this case, the government. As if the employer pays them no notice, then workers would not bother to join it. To do this they must show the employer that the employer has to listen to them, and that the employer will ultimately benefit from giving the union a seat at the table. This means that sometimes unions will let workers take action, like strike action, to show the bosses what will happen if the union is not listened to. They also need the employer to be a successful organisation - i.e. be profitable in the private sector or "affordable" in the public sector, as defined by the dictates of the economy and the global financial markets.

This gives rise to some problems. In libcom.org's introduction to the unions we go into this issue in detail. One key point is that:

once unions accept the capitalist economy and their place in it , their institutional interests become bound to the national economy, since the performance of the national economy effects the unions' prospects for collective bargaining. They want healthy capitalism in their country to provide jobs so they can unionise and represent them. It's not uncommon therefore for trade unions to help hold down wages to help the national economy, as the British Trades Union Congress (TUC) did in the 1970s, or even assist their national governments in mobilising for war efforts, as unions did across Europe in World War I, or as the militant US United Auto Workers (UAW) did in World War II, signing a no strike pledge.

Labour leader Ed Miliband addresses TUC conference

On top of this in the UK there are powerful links between most of the unions and the state, via the Labour Party which the unions set up and fund. So any deal on pensions made with the Conservative-LibDem coalition would have to be paid for later by Labour governments. And of course it was a Labour Lord who wrote the report the deal was based on. And many people will have seen Labour leader Ed Miliband's hilariously repetitive interview in which he makes clear his view that "the strikes are wrong".

In terms of knowing exactly why Unison sabotaged this particular dispute, that will probably never be known - unless one-day a high-ranking whistleblower comes forwards. But this almost never happens as there are lucrative career opportunities for senior union officials who don't rock the boat. Dave Prentis for example has recently been awarded a directorship of the Bank of England for his troubles. However, there is a clearly identifiable pattern of this kind of sabotage in every major dispute under both Labour and Conservative-LibDem governments, such as the pay disputes of 2008 or the pensions dispute of 2006.

What is most important, I believe, is that we realise that our interests as workers are not the same as the interests of "the unions". Unison fulfilled its needs in the dispute: to get the employers to give it a seat at the table it called us out on strike. And by presenting a slightly less worse deal to members - or in the case of the NHS scheme a deal which they tried to make look slightly less worse - they get to sell themselves to members by saying ‘look what improvements the union has got for you’.

A question of leadership?

Some people may say that, sure, this is a problem with Unison because Unison has a right-wing leadership. So the answer is to elect a left-wing leadership instead.

However, the problem is not simply one of leadership, it is to do with the structural role unions hold in capitalist society. This role is the same whether the unions are right or left wing.

And in terms of the actions which workers are permitted to take by the unions, these depend more on the level of self organisation and militancy of workers on the shopfloor than on the leadership.

For example, the teachers' union ATL, which is a relatively right-wing union took strike action on June 30. And the left wing, "socialist" Fire Brigades Union, which also broke from the Labour Party, did not take any action at all. Others have written in detail of how the left-wing PCS union has sabotaged other recent disputes, with the support of the Socialist Party.23

This can be seen more starkly when struggles are more intense, as in the examples I outlined above or in libcom.org’s introduction to unions.

Conclusion

In conclusion, I hope that I have demonstrated not that we lost the pensions dispute because workers were not willing or able to fight - but because the very organisations workers set up to defend ourselves have turned against us. And this has happened not because the leaders are bad people (although undoubtedly some of them are) but because of the nature of capitalist society and the role the unions play in it.

Now, I don't say this so that people will leave the unions. As I have pointed out, it was mostly rank-and-file union members and activists who made the strikes, especially November 30, such a success. And gave us a real glimpse of our power to disrupt the economy.

However, at the moment we do not exercise this power ourselves directly, but mediated and lead through our "representatives". And their interests are not the same as ours.

While our pensions have been decimated, our union leaders will retire on huge salaries.

As such, we cannot rely on the unions to lead us or organise a real defence of our jobs, pay and conditions, which are under severe attack in these austerity measures.

However, the unions have a monopoly of communication across groups of hundreds of thousands of workers. Which is not something which we can do as rank-and-file workers at the moment - although hopefully one day we will be able to.

So while we may not be able to just ignore the unions and struggle ourselves for the time being, there are things we can do here and now to put ourselves in a better position to defend ourselves.

It is looking like the next big fight for UK public sector workers is going to be against the pay freeze. Of course, it may be that the unions squash it before it gets started. However with real wages still falling while the cost of living continues to rise, they can only keep a lid on our anger for so long. So even if there is not a real fight in the next year there may be the year after.

I don't have all the answers, unfortunately, as this problem is a huge one. However, here are some practical tips for things we can do to get better organised in the future:

- Try to go on a workplace organising training course put on by the Solidarity Federation. This is a good primer to start getting organised in your workplace, with or without a union.

- In your workplace, instead of union meetings try to hold meetings for all workers in all unions and none, including permanent and casual workers.

- If you are trying to recruit your colleagues to a union, make sure you are clear with members and potential members that the union will not "help" members as such, we have to help out each other.

- Get ready to fight. This applies to you and your co-workers. These austerity measures are about saving the government money. The only way we can beat them is if we cause disruption which costs them more than the money they plan to save. It's not going to be easy, but it's the only way. If there is widespread support for strike action, the unions will find it difficult to put it off.

- Respect picket lines, and argue for colleagues to do the same. . Too often workers go on strike only to see their colleagues in other unions go into work. This makes all of our strikes weaker and only by sticking together can we shut down our workplaces and beat our bosses.

- Ultimately it will probably take workers taking unofficial action - or at least threatening to - to push the unions into actually organising effective action (as they cannot allow themselves to be sidelined by workers organising themselves). It's not easy and there is no quick fix but we need to start slowly building the ground work in our offices, hospitals, depots, schools etc to begin to take forms of action without union authorisation, such as go slows, work to rules, sabotage or even wildcat strikes.

None of this will be easy, but unless as workers we get organised independently once again, we will be led from defeat to defeat by our "representatives".

- 1 Joint strike action over pay would not have been possible either at this point because some groups of workers like teachers already had a pay deal, but this could be possible now.

- 2 Although unfortunately I could not get any meaningful data to evidence this other than my personal experience.

- 3 This was so pervasive that it was even believed by some "class struggle" anarchists! See this article and the comments below for example: http://libcom.org/blog/interview-new-british-organization-collective-action-14062012

- 4 One such exception would be the "decent pensions for all" campaign by the teachers' union, NUT.

- 5http://www.guardian.co.uk/society/2011/nov/02/public-sector-pensions-key-changes - retrieved on 18/10/12

- 6http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/business-15570669 - retrieved on 18/10/12. Such low turnout is typical of strike ballots of Unison over this time period.

- 7http://www.guardian.co.uk/society/2011/dec/08/government-new-offer-nhs-pensions - retrieved on 19/10/12

- 8http://www.guardian.co.uk/politics/2011/dec/20/danny-alexander-public-sector-pensions - retrieved on 18/10/12

- 9 http://www.unison.org.uk/asppresspack/pressrelease_view.asp?id=2527 - retrieved on 30/10/12

- 10 " If you cast forward to 2041, when today's 30-somethings will be retiring, the average retiree is expected to live until roughly 92. That would mean the state pension age could be somewhere between 70 and 76. It would mean that by the time today's children are retiring, a state pension age of 80 wouldn't be out of the question." From http://money.aol.co.uk/2012/07/09/rising-state-pension-age-you-may-never-retire/ - retrieved on 22/10/12

- 11 See this article for more detail on how this change will cut pensioners' incomes: http://touchstoneblog.org.uk/2012/03/switching-from-rpi-to-cpi-is-even-more-of-a-disadvantage-than-we-thought/

- 12 http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/business-13862791 - retrieved on 18/10/12

- 13 In the comments after this article: http://libcom.org/blog/unison-fighting-cuts-dr-it-21042011

- 14 http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-15910621 - retrieved on 30/10/12

- 15 http://www.unison.org.uk/asppresspack/pressrelease_view.asp?id=2540 - retrieved on 13/10/12

- 16 http://www.hm-treasury.gov.uk/press_146_11.htm - retrieved on 23/10/12

- 17 http://www.unison.org.uk/asppresspack/pressrelease_view.asp?id=2643 - retrieved on 24/10/12

- 18 http://www.unison.org.uk/asppresspack/pressrelease_view.asp?id=2685 - retrieved on 23/10/12

- 19 My emphasis

- 20 My emphasis

- 21 Transfer of Undertakings (Protection of Employment)

- 22 In my comment dated 21/04/11 below this article: http://libcom.org/blog/unison-fighting-cuts-dr-it-21042011

- 23 http://www.socialistparty.org.uk/articles/15132/31-08-2012/pcs-wins-significant-jobs-agreement-in-hmrc - retrieved on 30/10/12

Comments

Thanks for the article, very

Thanks for the article, very well constructed- will share it with some public sector workers I know.

ok, finally got a chance to

ok, finally got a chance to read this. it's really good, nice work. the detailed chronology is really useful - even as someone who followed the dispute and already has a critique of the trade unions, it really lays bare how they demobilised the conflict.

the only thing that jarred slightly was the structural critique towards the end. i think it's fine, because it links to the libcom critique of unions, and then gives examples of left wing socialist leaders being shit too. but that was the only bit where i thought 'would this persuade me if i wasn't already convinced?'. I think, with the links and examples, it probably does. obviously it's a truncated form of a longer argument, and the longer argument is hyperlinked.

This piece also got me thinking about a more general point about militancy. People (including us) often talk about militancy as if it's more or less a given thing ('the level of struggle' or whatever). At the macro level, it appears like that (e.g. we can say there's a lower level of struggle today than in the 1970s).

But at a micro level, militancy's a lot more dynamic. There's often not much, but then a dispute flares up and there's a huge upsurge in support for action. Much hinges on what happens next. This piece is an excellent example of the standard trade union playbook. It's not that the class is constantly straining at the bit and being held back, but that (a) the TUs (above lay rep level) don't do much to agitate for mass action and (b) when the appetite is there for sustained mass action, they work to diffuse it by stringing things out until everyone's demoralised.

This in turn, informs the 'macro' level, because after all, what is the level of struggle if not a general increase in the number of sustained, mass struggles overlapping with one another. As long as trade unionism retains its grip, there will be no return to periods of mass struggle (as you say in the piece). There's probably also feedback effects - seeing lots of successful struggles around you, makes you more likely to follow suit.

But yeah, this piece got me thinking about these kind of dynamics. If we have any ability to influence things at all, it's at the micro level, though obviously it's not easy. It would also be interesting to compare the trade union demobilisation to management textbooks on 'managing change'. Reading through management textbooks to show how they think and operate has been one of those projects on the back of my mind for a while. ('change management' was itself a response to the relative instability of neoliberalism/postfordism/deregulation/whatever, e.g. see here). Iirc, there's some model of managing change with a 4 step process: 1st letting people know and letting them vent a bit, then letting it settle in while nothing/some sham consultation happens, then forcing it through over and residual resistance, then consolidating the new regime. It seems like the TUs play literally a textbook role in managing and diffusing worker discontent.

This is really good piece

This is really good piece Steven. I have no doubt it took quite a while to bring together and I'm glad you did it, basically.

JK

You and me both comrade. Maybe time to sign up for that masters.... Or at least start some sort of genuinely productive working group.

Thanks for your comments,

Thanks for your comments, guys

Joseph Kay

yeah, I thought this as well. However, I didn't want to go over and reiterate all the points from the libcom introduction to the unions, or other articles like Ed's "red flags torn", or my response to Ewa. So I just summarised and linked.

I think maybe if we published this as a pamphlet we should put the unions intro in as an appendix

I pretty much agree with that.

I'm not sure you could say it's the same process, exactly, but certainly it's not entirely dissimilar. Basically what they seem to do in these national disputes is in the "resistance" phase offer a bitter token resistance, like a safety valve to let workers blow off a bit of steam. Then shut it off, pending while negotiations, meanwhile workers go into the "resignation/acceptance" phase, so the mood for further action dissipates.

Excellent article. Solid

Excellent article. Solid piece of work.

Quote:

It would also be interesting to compare the trade union demobilisation to management textbooks on 'managing change'. Reading through management textbooks to show how they think and operate has been one of those projects on the back of my mind for a while. ('change management' was itself a response to the relative instability of neoliberalism/postfordism/deregulation/whatever, e.g. see here). Iirc, there's some model of managing change with a 4 step process: 1st letting people know and letting them vent a bit, then letting it settle in while nothing/some sham consultation happens, then forcing it through over and residual resistance, then consolidating the new regime. It seems like the TUs play literally a textbook role in managing and diffusing worker discontent.

I'm not sure you could say it's the same process, exactly, but certainly it's not entirely dissimilar. Basically what they seem to do in these national disputes is in the "resistance" phase offer a bitter token resistance, like a safety valve to let workers blow off a bit of steam. Then shut it off, pending while negotiations, meanwhile workers go into the "resignation/acceptance" phase, so the mood for further action dissipates.

Have to broadly agree with your final response. Coming from the private sector, I've had some experience of similar outcomes but I have to say that there have been occasions when, in national negotiations covering several sites, a strong push from elected representatives could have significantly moved things forward (particularly when it comes to strike action). I think the reasons here lay (without going into too much detail) 1. with the degree of organisation at individual sites, 2. historical successes/failures at individual sites and 3. the failure of elected representatives to effectively transmit demands from the shop floor.

yeah good piece overall,

yeah good piece overall, particualrly liked the chronology but would say that.i also think jumping staright from unison does x to all unions do x jars a little.

Unison are a particularly bureaucratic set up even by TU standards.So you'd have to be somewhat more rigourous and tbh more measured to apply exactly the same critiques to a smaller and a bit less bureaucratic union like the RMT for example,even if the overall ''structural contradiction'' of a union within capitalism is the same whereever you go.

Thats just my view on the conclusion though, thought the rest of the article was good.

Yeah, I had a similar

Yeah, I had a similar conversation with a comrade not too long ago. They were saying, in particular, that the strongest critics of trade unionism seem come from UNISON members. I guess the way I see it as that UNISON is a good example in that it very quickly comes to demonstrate the contradictions and limitations of trade unionism. That said, we do have accommodate our arguments (which I think are fundamentally correct) so that they still speak to trade union activists who may come from traditionally more militants unions or more rank-and-file oriented branches.

I mean, the contradictions and limitations are still there of course, but I don't think we do ourselves any favors by pretending all unions are as shit as UNISON (not saying Steven's article does that, btw).

cantdocartwheels wrote: yeah

cantdocartwheels

hi, yeah as I said I feel the same way. But I feel that we do that in the unions in general in the libcom introduction that I link to from the text. I do also specifically mention the FBU, which didn't take any action at all, and PCS which is linked to from the text. The unions introduction also links to Ed's article which goes into the CWU sabotaging the 2007 strikes.

Steven.

Steven.

yeah i know that you mention some other unions, i also realise there are space constraints in any article. It was just a observation about the conclusion, i thought the rest of the article was really good.

I think its worth mentioning though, because as you know its not just about the leftist arguement about ''good and bad union leaders'' which you rightly deconstruct, its also about the militancy of the membership, its socio-economic make up, and the level of ''autonomy'' or ''initiative'' granted to/taken by rank and file activists; both being obviously higher (in relative terms) within some unions than others. The latter being particularly low for unison as your article points out.

Difficult to always squeeze everything in, and might ended up as a tangent in this case, but I would say that not covering the RMT et al or finding a nuanced means of criticising more militant unions kinda ends up weakening your critique.

Anyways should probably split this post on to a new thread though if people wanted to carry o the discussion though, coz this is a largely good article...