The history of a militant strike of streetcar workers in Kansas City in 1917 by Jeff Stilley, during which the population of the town drove out scabs who had been brought in by the employers.

The purpose of this blog post is to present information gleaned from newspaper sources. The papers used are: The Kansas City Star, The Kansas City Post, and The Kansas City Journal. These are all available on microfilm at the State Historical Society of Missouri. Newspapers are often wrong, so read with a critical eye. I have combined information from dozens of articles from each of the three papers to create this narrative.

The drawing above is from The Star August 11 main edition. State Historical Society of Missouri, microfilm.

+++++++++++++++++

“The strikebreakers say quite frankly they never had such an experience before as their reception here, and they want no more of Kansas City.” Post August 13

The above report came from a makeshift encampment of 550-800 strikebreakers, or “finks” as strikers and sympathizers referred to them, by the Little Blue River one Sunday evening in the summer of 1917. The men were bruised, dirty, and hungry. They were also very angry.

Some of them claim to have been convinced to come to Kansas City under false pretenses (Star August 14 main ed claims all those deported were experienced strikebreakers). They were promised easy work with high pay if they hopped aboard a train from cities like Chicago, Philadelphia, Boston, Buffalo and New York. Others were more experienced with this line of work and had broken other, much larger, strikes around the country. Their mission was to operate streetcars in Kansas City for the Kansas City Railways Co., which had hired Berghoff Brothers & Waddell to import men for the job.

Some of the experienced finks were also New York mafia members. Eddie “The Runt” Costello of the “distinguished” East Side Costello gang led these. He appears to have been the older brother of Frank Costello, Boss of the Luciano/Genovese Family from 1937-1957, although this is not confirmed. Regardless, Eddie was quite happy to tell reporters details of the strikebreaking business (Post August 14).

The Costello gang regularly worked with Berghoff Bros & Waddell, a company that specialized in breaking strikes all over the country. At the end of a day on a streetcar job, each crew turns in 10 cents to the company, 25% to Berghoff’s men, and they pocket the rest. Typical practices, with the threat of violence to back them up, included never accepting transfers, overcharging customers, and demanding more money at the bottom of steep hills. Kansas City’s citizens feared such activities, and worse, if strikebreakers were brought in from ‘The East.’ The mafia had broken much larger strikes in New York and Seattle, and expected Kansas City to be an easy job. They never made a penny.

Drawing of James A. Waddell of Berghoff Bros & Waddell. The Star August 11 main ed. State Historical Society of Missouri, microfilm.

++++++++++++

On August 1st, nine streetcar employees met with the Carpenters’ Union local 61 to discuss unionizing the Kansas City Railways Co. The motormen, carmen, and power plant workers complained of impossibly long days, often with split shifts (meaning they were not on the clock the whole day). They were paid less than in other big cities, and management tolerated zero complaining, nor discussions of grievances.

The nine employees, plus 16 others interested in forming a union, were fired the very same day. According to the workers, the company used a thorough spy system that tipped them off. Only a couple weeks earlier (July 7 – 13), 290 workers in the power plant (2nd & Grand) engaged in an unorganized walkout strike that won them shorter shifts (from 12 hours to 8 hours, still 7 days a week), but the company refused any right to organize.

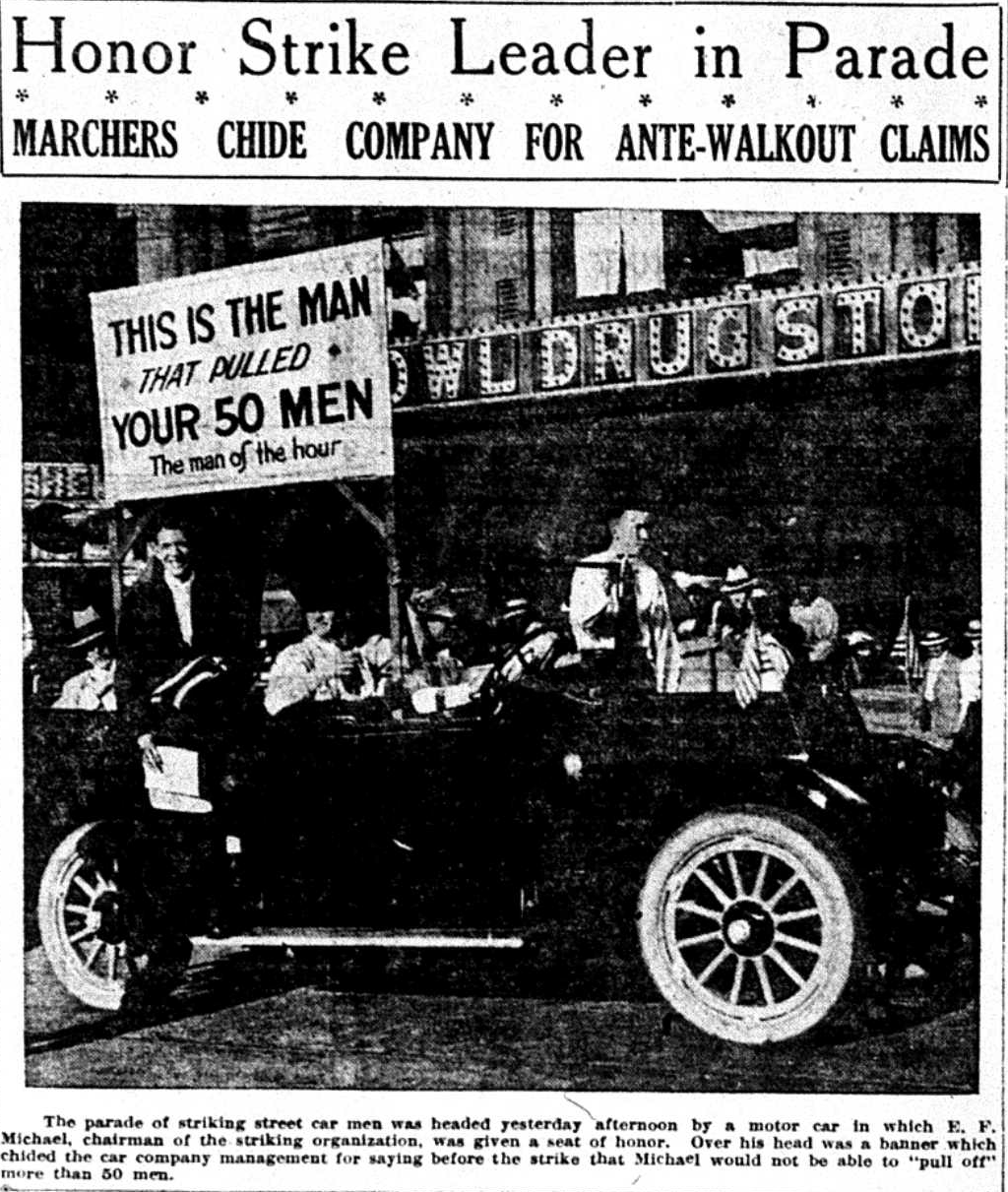

When the leader of the fired employees, E. F. Michael, threatened to organize a strike of the streetcar system, the owners told him he wouldn’t be able to get 50 men. With the help of organized labor in Kansas City, headquartered at the Labor Temple (14th & Woodland), the streetcar system in Kansas City, MO, Kansas City, KS, and Independence, MO, was completely shut down exactly one week later.

Photo of E. F. Michael, organizer of the streetcar shut-down. The Post August 10, State Historical Society of Missouri, microfilm.

++++++++++++++

On Wednesday, August 8th, the strike officially began at 4:35am. It took about twelve hours to completely shut down service, but they did. By that time, roughly 1800 of the 2200 employees they were targeting had signed the strike pledge. They also signed up to start a local of the Amalgamated Association of Streetcar and Electric Railroad Employees of America (now the Amalgamated Transit Union). Magnus Sinclair, organizer for the AASEREA, quickly arrived in Kansas City to help direct activities.

The strike leaders’ demands were quite modest: the right to organize a union (open shop), and the reinstatement of all workers fired from August 1st on. The specifics of working conditions, work schedules, and pay could be worked out in negotiations and arbitrations later. The organizers even left the company’s power station employees on the job, in order to avoid inconveniencing people and businesses that also relied on the electricity.

The first day saw hundreds of strikers and their family members crowd around car barns at 48th & Troost, 9th & Brighton, and 10th & Minnesota on the Kansas side. These crowds used rational arguments and public shaming to convince crews to quit and walk to the Labor Temple throughout the day. Teamsters helped out by blocking tracks with their trailers. A few rocks were thrown in the windows of streetcars around the city, but compared to similar strikes around the country at that time, the Kansas City Police Department was very impressed with the discipline shown by the strikers the first few days.

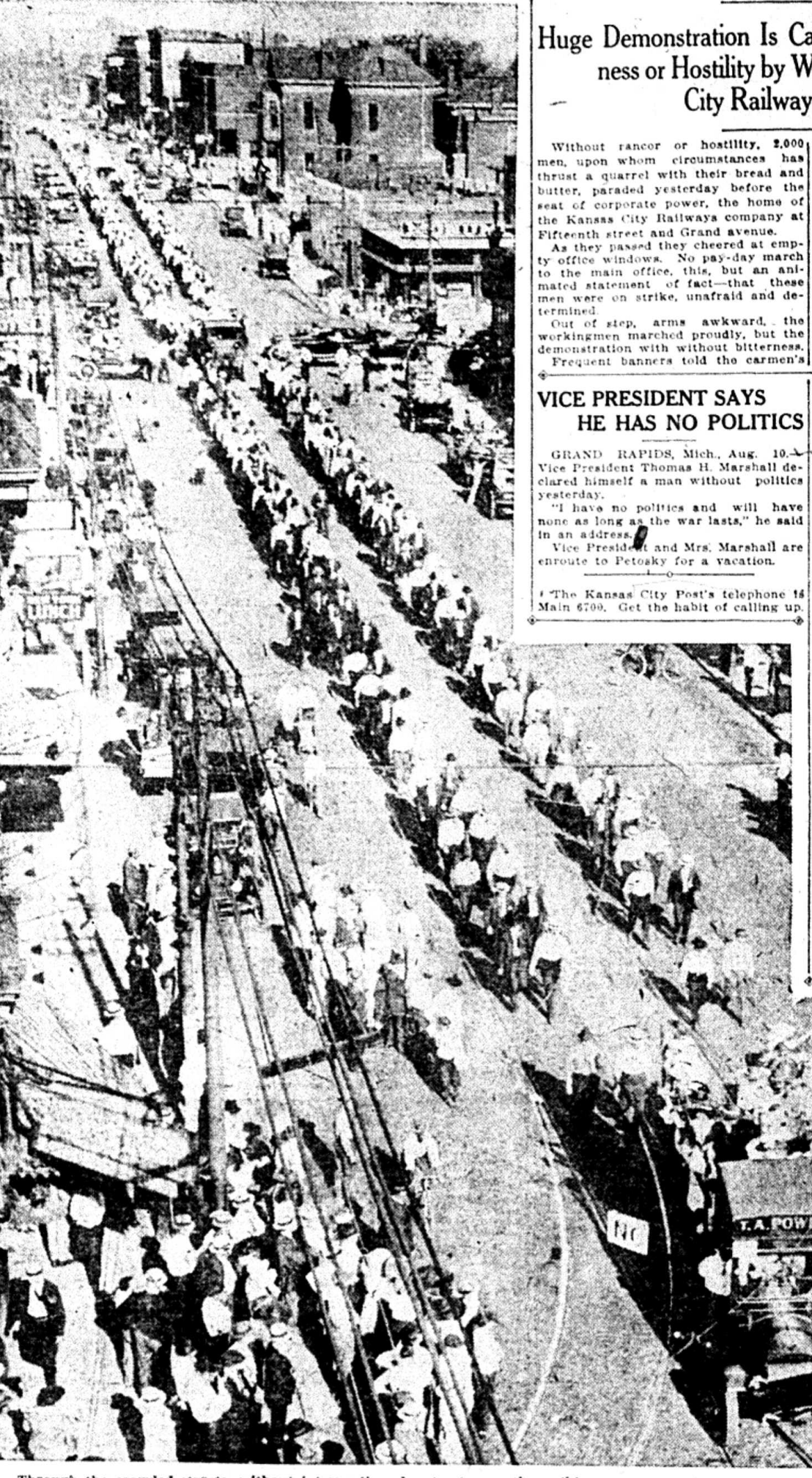

The second day saw a parade of at least 2,000 strikers downtown. The parade passed by the headquarters of the KC Railways Co (15th & Grand), but the office staff was threatened with termination if they looked. With the streetcars not in operation the company was paying loyal workers to enjoy a few days off, yet the strikers still kept adding more to their rolls. The organizers received word from AASEREA locals in other cities that strikebreakers were being rounded up for Kansas City, which the company emphatically denied.

Friday the 10th, the third day, KC Railways Co admitted to bringing in strikebreakers in an attempt to resume service within 24 hours, to the outrage of the city. The Labor Temple alleged there were already 600 from New York in the city (Star August 11 main ed, Journal August 11). Strike organizers threatened to shut down the power plant, and the Building Trades Council claimed they could get 6,000 sympathy strikers, if finks were used (Post August 11).

Photo of strikers’ parade at 15th & Grand (KC Railways Co headquarters). The Post August 10, State Historical Society of Missouri, microfilm.

++++++++++++

Considering the central role the streetcars played in transportation for the city, residents took the incredibly inconvenient strike in stride. Some companies provided trucks to shuttle their employees, and some wealthy families picked their domestic workers up in their limousines. Thousands of jitney automobiles clogged the roads looking for stranded people. Many simply got a lot of walking in. Working women of the city (concentrated in candy manufacturing, department stores, hotels, laundries, and garment manufacturing) organized walking groups by neighborhood to get to and from work for the duration of the strike.

City officials took a neutral stance in the strike, even though the city was a part owner of KC Railways in return for their monopoly status. The police department announced they will only protect people and property as needed, and would take no part in helping to break or win the strike otherwise. If anything, city officials were irritated with the management of the company. In an unrelated series of events, Mayor Edwards began the strike publicly criticizing the company for having promised the city to provide streetcar lamps for city street signs at no cost, only to later demand payment for the space.

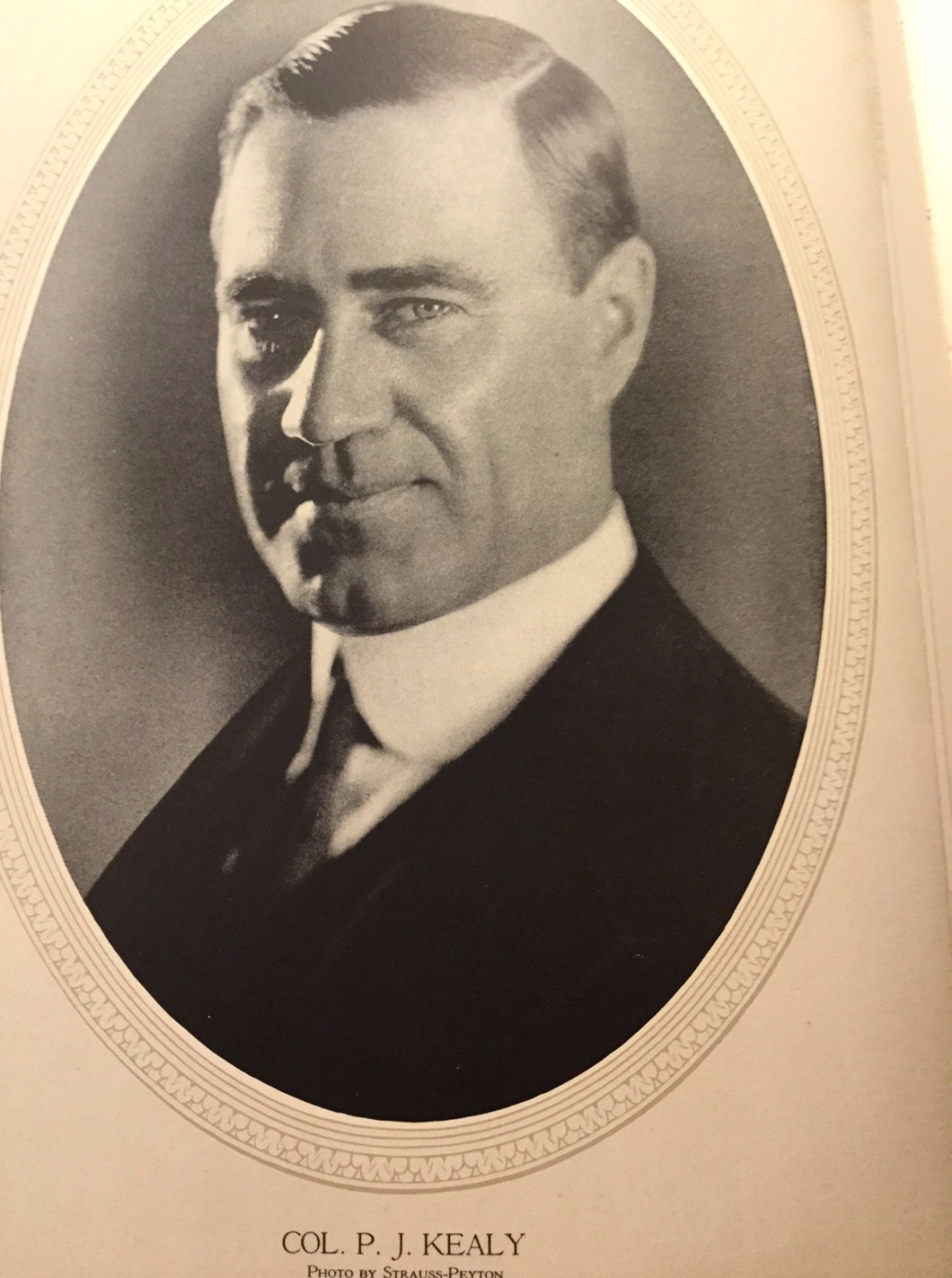

The company crossed the line, however, when it lied to city officials on the second day regarding bringing in strikebreakers. Even after they admitted it the next day, they refused to tell officials where they planned to house them. By the middle of the strike, city officials accused the company of attempting to incite so much violence that troops would have to be brought in. The closest contingent of troops was commanded by, coincidentally, Col. Philip J. Kealy — President of KC Railways Co (Star August 13 main ed, Post August 14).

Once the importation of strikebreakers was announced, Kansas City, Kansas, officials declare that any strikebreaker who steps into their city will be arrested immediately. They also worked with Kansas City, Missouri, council members to ask the courts to put the private company into receivership, in order to do away with the recalcitrant management of the streetcars. For good measure, Kansas officials even discussed declaring martial law — not to break the strike, but to seize the streetcars and run with regular employees.

Amidst the strike, dozens of Kansas City, Missouri, police officers inform their commanders they will refuse to protect strikebreakers attempting to run cars (Star August 11 main ed, Post August 11, Journal August 12). This act of solidarity led to the termination of 43 officers who refused strike duty. The police commissioners, who were appointed directly by the governor of Missouri, carried out the firings.

Photo of Col. Philip J. Kealy, President of KC Railways Co. Kansas City and its 100 Foremost Men, published in 1925 by Walter P. Tracy. The Missouri Valley Room at the Kansas City Public Library.

++++++++++++

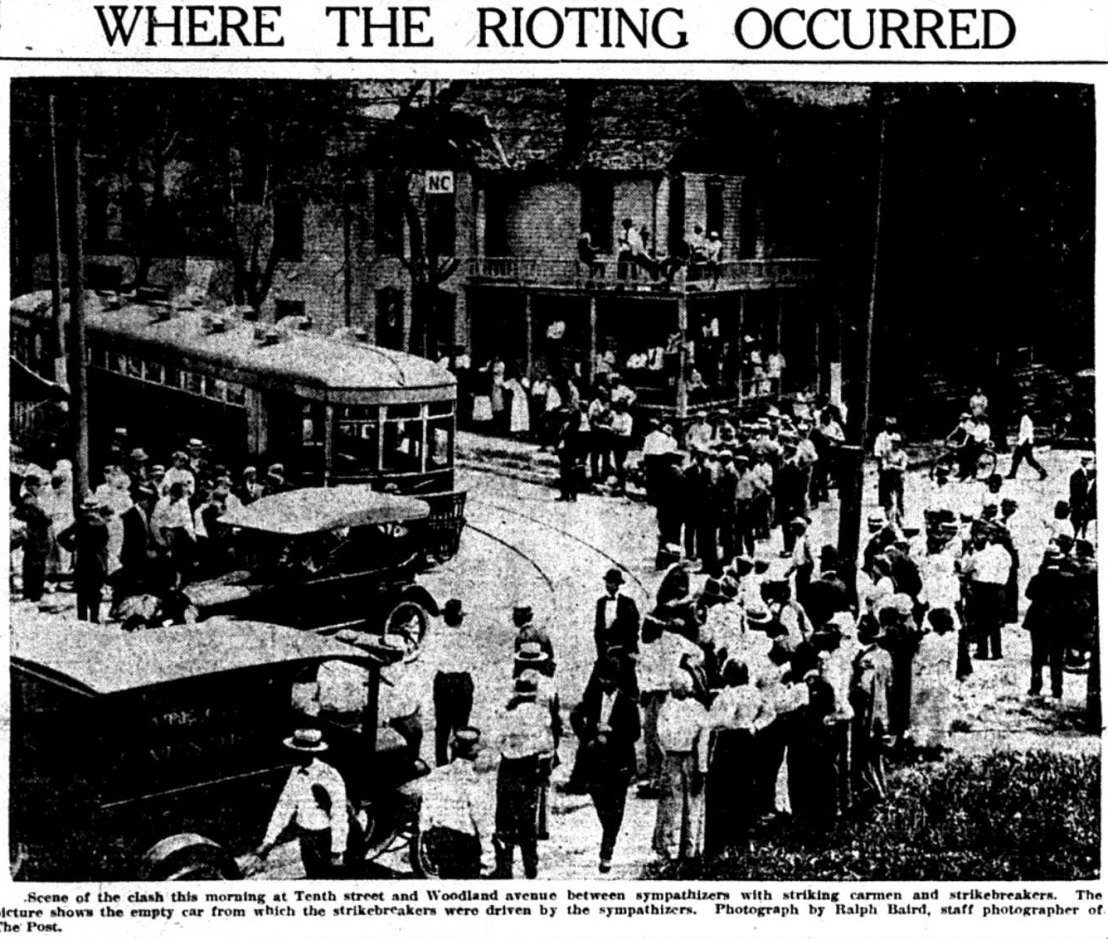

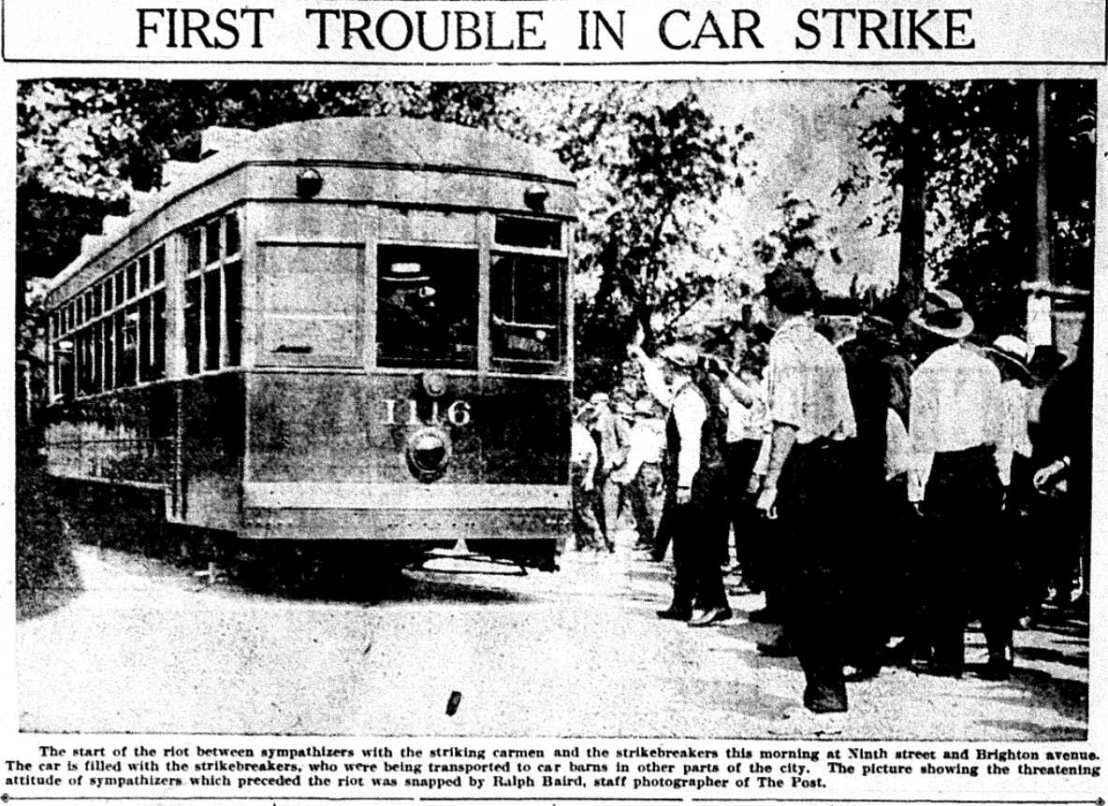

The confrontation between citizens and finks erupted at 10:45am on Saturday at 10th & Woodland. The company attempted to move some finks from 9th & Brighton to 10th & Euclid. Teamsters and citizens blocked the streetcars with their wagons and automobiles. The riot started after the crowd cut the trolleys from their electricity wires, and a strikebreaker threw a brick at the crowd in retaliation (Star August 11 main ed, Journal August 12, Post August 11). Later, when two strikers — who attempted to board a streetcar to convince the finks to go home — were struck with Berghoff Bros & Waddell provided blackjacks, the crowd of 300 men, women, and children filled the air with rocks and bricks (Post August 11).

By early afternoon, the strikebreakers had either escaped the area entirely, were holed up in a building prepared for them at 10th & Euclid, or were locked in the Labor Temple. Throughout the afternoon, the crowd turned truck after truck of food and supplies intended for the besieged strikebreakers at 10th & Euclid back. In one particularly intense incident, several hundred to one thousand sympathizers hurled dinner plates at the building full of strikebreakers. At least one strikebreaker began firing a gun from inside in the direction of police officers. 35 officers then stormed the car barn and confiscated their weapons. In another shooting incident, the local Teamsters business agent was shot near his heart. Somehow, no one was killed. There were four serious injuries, and many dozens of bloodied and bruised people (Star August 11 main ed, Post August 11, Journal August 12).

Without the heroic efforts of strikers and the police, much more violence would have occurred. William Wiley, a company spotter, was saved from a 500-person mob looking for blood at 14th & Brooklyn. A number of finks were rescued from a surrounded butcher shop they had fled to, and marched to a locked room in the Labor Temple. They were soon joined by more rescued strikebreakers from a streetcar.

Photo of damaged streetcar at 10th & Woodland where strikebreakers were driven out. The Post August 11, State Historical Society of Missouri, microfilm.

+++++++++++++

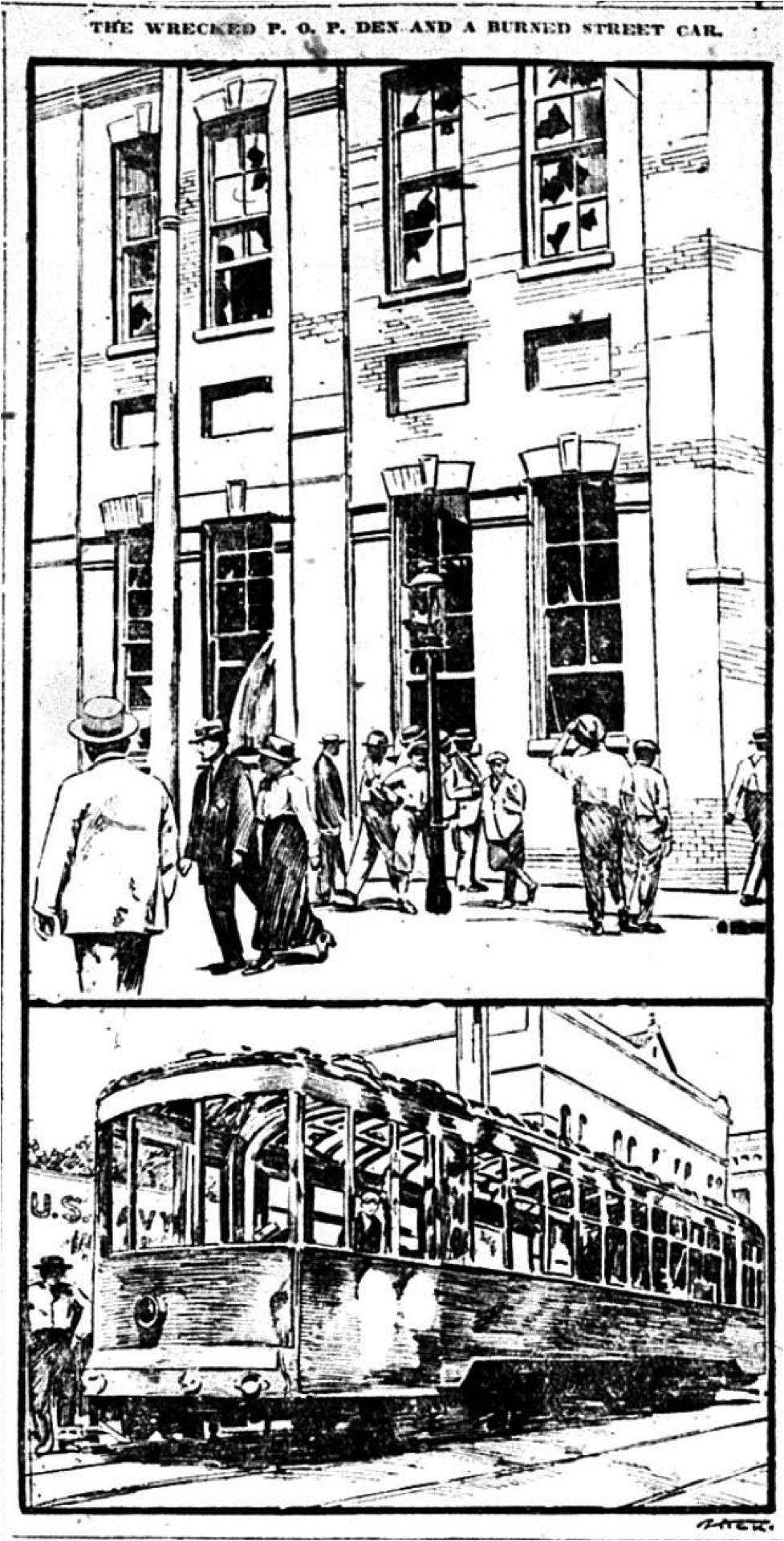

That night, Saturday the 11th, 400-480 strikebreakers were marched through city streets with their hands up to Union Station from 10th & Euclid where they were herded onto train cars. Residents along the way cheered the strikers and police who protected the finks from a trailing 5,000 person mob. For hours they had been huddled on the second floor of the building, as a crowd – first of hundreds, then thousands, then 10-20,000 – continuously hurled rocks and bricks through the windows.

They surrendered after the crowd threatened to set the building on fire. A damaged streetcar outside the barn was set ablaze with 100 ft high flames to demonstrate, as the crowd chanted, “Burn out the finks!” The Chief of Police himself, Thomas P. Flahive, pleaded with the mob for over an hour to prevent them from committing mass murder and to allow safe passage.

Part of the mob then went to harass 200-400 more strikebreakers at 9th & Brighton. This group of strikebreakers left the barns at 1:00am and walked along the train tracks to Union Station again under union and police protection. Another part of the mob, 2,000 strong, went downtown to try to find Leo Berghoff and drag him out of his Hotel Baltimore room, but he was gone (Star August 12 Sun ed, Journal August 12).

The Kansas City Star estimated the crowd of strike sympathizers at Union Station to be 5,000. The Kansas City Journal estimated the crowd of strike sympathizers at 10th & Euclid reached 20,000 between 9:00pm and 10:30pm, or so. All the newspapers state with confidence that the great majority of the various mobs from morning through the night were not strikers, but citizen sympathizers. Trucks of strikers were dispatched throughout the day to prevent these mobs from murdering strikebreakers.

A conservative estimate for the number of citizens actively taking part in driving the strikebreakers out of the city from Saturday morning into early Sunday morning is 10,000. It is very possible the number was much larger, although some in the crowd at 10th & Euclid around 10:00pm were no doubt spectators, looking for some excitement. Nonetheless, the swift and violent confrontation on the part of thousands of citizens gives an idea of how outraged much of the city was by the idea of armed and violent strikebreakers coming into their city.

It is difficult to ascertain exactly how many strikebreakers were in the city at this point. Berghoff Bros & Waddell were attempting to bring over 2,000 to the city by Sunday night. It appears between 1,000 and 1,400 were in town by the time the riots occurred. Some had certainly escaped the melee to lay low for a couple days in the city. Those locked in the Labor Temple apparently left town that night without being herded onto train cars with the others.

Photo of a confrontation between strikebreakers trapped in a streetcar and strike sympathizers at 9th & Brighton. The Post August 11, State Historical Society of Missouri, microfilm.

++++++++++++++

Sunday afternoon, August the 12th, the 550-800 strikebreakers’ train cars were hooked up to an engine, which headed out of the city east. The finks had not eaten since early Saturday morning. They made attempts to get food inside Union Station, but were forced back into their cars each time. Their cars were pelted with bricks and stones as they passed through Sheffield. The train slowed to a halt in Blue Township, by the Little Blue River (near present-day 39th & Little Blue Parkway). According to one report (Post August 13), the conductor told them to get out, which they refused. When he started slowly backing up toward Kansas City, all 550-800 jumped off the train (Star August 13 morning ed, Journal August 13).

The angry, bruised, and hungry men immediately emptied a small grocery store and washed themselves in the river. Berghoff Bros & Wadell agents also visit them in the middle of Sunday night to coax them back to Kansas City, but the men refused. Monday, they began raiding the local farms for chickens, corn, apples, and anything else they could find. Local law enforcement officials visit the men to tell them they have to get out within 24 hours, and threatened KC Railways Co to get them out of Kansas City, or county deputies would by force. After such treatment, Eddie Costello vowed to ‘get’ Leo Berghoff when they returned to New York. Kansas City residents, anyway, hanged Leo Berghoff in effigy at 27th & Main Monday night.

There were rumors that hundreds more strikebreakers were en route from Chicago, and that Berghoff Bros &Waddell was given a budget of $1 million to do whatever it took to break the strike. 300 strikers allegedly took an oath to prevent strikebreakers from operating the cars with their lives, if necessary. Such drastic action would not come to pass (Star August 13 morning ed, Journal August 13).

Drawings of the post-weekend riot wreckage. The Star August 13 morning ed., State Historical Society of Missouri, microfilm.

+++++++++++++

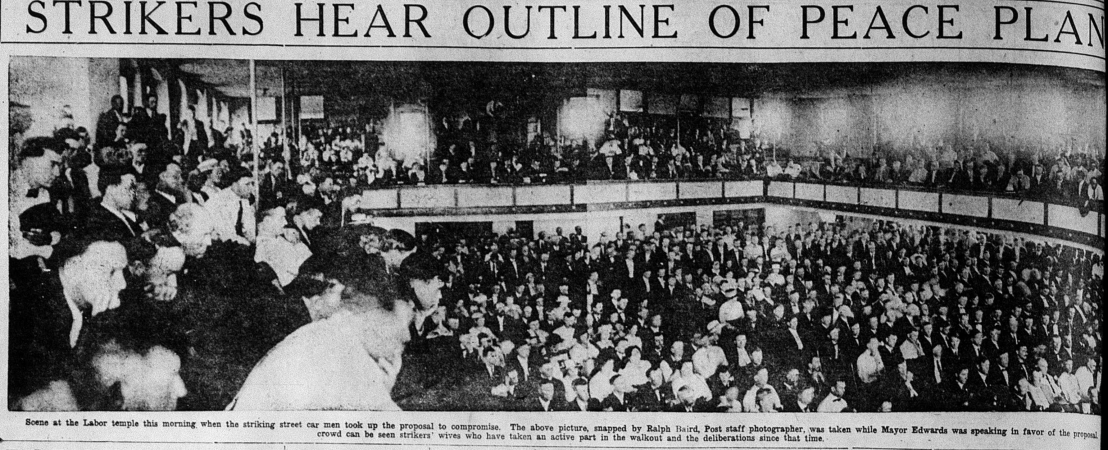

The streetcars did not run again until Friday the 17th, after a total victory for all demands of the strikers. Almost every single employee of KC Railways Co (about 2600) joined the new union.

Mass parades and meetings continued early the week of the 13th, and switchmen at Kansas City Southern began refusing to send coal cars to the Railways’ power plant. Poor weather and fewer jitneys on the roads began to cause public grumbling on Tuesday, when a Department of Labor mediator named Frederick Feick arrived to bring closure. Also on Tuesday, Federal Judge Martin Wade of Iowa issued a blanket injunction at the request of the company to stop anyone from preventing the operation of the streetcars.

Mediator Feick was able to get Judge Wade to delay any action on the injunction, and brokered a deal Thursday the 16th. After the strikebreakers were brought in, the strikers upped the ante to also demand a closed shop (union membership required). This was dropped in the end, and all of their original demands were met.

Photo of the streetcar strikers on the 16th at the Labor Temple — they are about to vote to end the strike. The Post August 16, State Historical Society of Missouri, microfilm.

++++++++

At a Labor Temple mass meeting Tuesday morning the 14th, Phoebe “Mrs. Henry” Ess, an influential middle class reformer in Kansas City and across Missouri, told the strikers, “Thousands of good citizens are behind you. We want you to win.”

Following the riots on Saturday the 11th, Chief of Police Thomas P. Flahive was quoted saying, “This is the most wonderful event in the history of the world. Capitalists have brought strikebreakers to town, and the citizens, not the strikers, have run them out” (Journal August 12).

Taken from https://stilleysociology.wordpress.com/2016/09/17/first-blog-post/

Comments