An analysis of how rape culture permeates yesterday and today's right-wing narrative, and of how anti-fascism sometimes failed to face it, with violent consequences. Part 1 of an article by the Nicoletta Bourbaki collective, published on Wu Ming's website.

To read the second part of this piece, see here.

Content note: this article contains repeated mention of sexual violence

1. Hunters of ‘cute dead girls!’

A blonde girl, little more than a child, lying in the dirt and dust like a rag doll. Placed in an unnatural position, the white dress in pieces and pulled up to reveal a body suggesting every kind of violence. A disturbing image, leaving observers speechless and filled with horror, also because of their inability to locate it in time and space.

Nobody knows who the young victim in the photo is.

The image arrives on the Internet on November 23, 2009, in the ‘vintage and black & white medicine’ section of a photography forum, after a similar post dated October 20 was deleted for unknown reasons. Since then, it has had some success on sites for fans of the genre, like the thread on a Spanish forum entitled Cute dead girls! where on October 10, 2010 it was posted by the user Nifelheim together with 29 other images, all of them revolting.

During this phase, the only keywords to find it, with a few variations, are ‘cute dead girls’. This is how the person who invented a story for this photograph may have found it. Perhaps a regular visitor to those forums, or simply someone who was searching ‘cute dead girls’ on Google.

On December 21, 2011 the photo is accompanied for the first time with the caption ‘Victim of Beria’, the head of the Soviet Union’s secret police under Stalin, and here called ‘Jewish rapist and mass murderer’. There is no evidence for this attribution, including whether Beria was Jewish, but an anti-semitic twist always goes down well in certain places and allows the writer to fantasise about the ‘Jewish origins of Bolshevism’. This will have some success on Ukrainian, Polish, Baltic sites.

Relatively late, about 2015, the image is associated with a German woman raped and killed by the Red Army. This use, at first limited to openly fascist sites, will be appreciated in Scandinavian countries and then the fictitious story will be even more developed in France:

Jeune fille allemande violée et tuée durant la seconde guerre mondiale, certainement par l’armée rouge. La guerre est le terrain de jeu préféré des violeurs, ce n’est pas juste une histoire d’hommes bien virils qui se tapent sur la gueule.

[German girl raped and killed during World War II, undoubtedly by the Red Army. War is rapists’ favourite playground, it’s not just very masculine men fighting each other.]

The photo comes to Italy very late. On April 3, 2017, right on time to begin our local fascists’ danse macabre against the Liberation, the girl becomes Luciana Minardi – a volunteer in the Women’s Auxiliary Service of the Decima Flottiglia Mas – and the photo accompanies an article by someone called Claudio Laratta.

The disappearance and probable violent death of Luciana Minardi in May 1945, because of the lack of reliable confirmation and sources, gives an opportunity to everyone who wants to destroy the image of the Resistance movement.

Finally, in September 2017, in the underworld of neo-fascist forums, the body in the photo becomes that of Giuseppina Ghersi.

Who is the girl in the photo? Perhaps we'll never know. It could be that she was the victim of a murder some time during the black & white era, photographed by the police before someone stole the image. A woman whose hypothetical descendants are completely unaware of the wide circulation of the image and of how it's used.

With the exception of the man who decided to kill her again while he was browsing through necrophilia sites, at least a dozen other individuals consciously created a fake while reposting, attributing to her an identity or a nationality. So many men have defiled the image of a murdered woman by making spurious accusations of rape. Cannibals.

In the case of Giuseppina Ghersi this is not even the only fake photograph.

There's another one, that's been around for at least 10 years.

[The Getty visual media company, which has this photo in its catalogue, states it was taken in Milan on April 26, 1945. It was exhibited at Turin's Isoreto (the Piedmont Institute for the History of Resistance and Contemporary Society), during The long liberation, 1943-1948 exhibition and can be seen in its photo gallery. The historian Marco Dondi writes in his book La lunga liberazione. Giustizia e violenza nel dopoguerra italiano (‘The long liberation. Justice and violence in the Italian postwar period’, Editori Riuniti, Roma 1999):

in Milan […] women's faces are marked with the letter M – the initial for Mussolini and for Legion Ettore Muti.]

The Autonomous Legion Ettore Muti was a military body of the Republic of Salò. In Milan it was responsible for large roundups, torture and summary executions. Its brutality includes the Piazzale Loreto slaughter (August 10, 1944), an event that deeply shocked the city and, a year after, led to the decision to display the Duce's body in the same square. It's been established that Legion Ettore Muti acted thanks to a wide network of informers, men and women. It's plausible that the young woman in the photo was among them.

What’s more, the image also appears in a book that Italian neo-fascists and revisionists know very well: Storia della guerra civile in Italia 1943-45 (The history of the Italian civil war 1943-45, 1963) by Giorgio Pisanò, a fighter for the Republic of Salò. In the chapter regarding April 25 in Lombardy, he comments on the image:

April 28: a young woman, guilty of supporting the Republic of Salò, is shamed by the partisans: Mussolini's “M”, as a sign of contempt, is painted on her forehead.

A demonstration that fascists, in their pseudo-historical reconstruction, lie and know they lie.

2. Rape in male and macho narrative

You need a strong stomach to search these outlets of horror for ‘photographic proof’ to link to any victim, useful to a hate and misinformation campaign. Yet there's always someone with a strong enough stomach. This is the nature of the comments of those spreading Giuseppina Ghersi's fake photo:

‘There's the photo of the little body with the knickers still down. Someone raped and killed her, these are the facts. Not the partisans? Maybe a black?’

The partisans or the blacks raped her. Black, meaning n*****s.

[‘These are the facts.’]

The horror and stupidity of these few lines aren't accidental: they are the predictable effect of a narrative, the rape and murder of Giuseppina Ghersi, which has no connection with historical reconstruction and has its origin in scandalmongering crime news.

There are many versions of Ghersi's last few days, not only completely unproven but also completely imaginary. In our post about her case we've dismantled them one by one, starting a number of research studies to find out what really happened to this poor young woman. Work in the archives of several different cities is ongoing.

We use the expression ‘alleged rape’ not in the despicable way it is usually employed about victims of sexual assault, forcing them to carry the burden of proof. We still remember very clearly the range of obscenities used to protect the suspects in the case of the American students who, on September 7, 2017, reported being raped by two Carabinieri on duty. They were drunk, they were asking for it, first they agreed and then cried for help, they wanted to make some money from rape insurance...

No, we say ‘alleged’ because we aren't looking at a woman reporting rape, but at men who 70 years after the facts start talking – out of nowhere – about a rape using exclusively toxic narratives, deliberately ignoring the story of the actual young woman who would have suffered it. Yes, she really existed.

We are not questioning a woman's account of the rape she suffered, but the account that men give of a rape in order to incite hatred and to manipulate an individual’s history and collective history. Using women once again, once too often.

3. Is a rape ‘just’ a rape?

Flipping through newspaper front pages from June to September 2017, it seems as though Italy was having a ‘rape emergency’. But despite the overexposure of a few cases (in Rimini, Florence and Rome) the question of sexual and gender violence is completely missing. This is only an apparent paradox because, as Valigia Blu spells out, these blanks are then filled with heavy doses of macabre sensationalism.

Rape only becomes ‘newsworthy’ if it contains elements that can be narrated following pornographic patterns – and if there aren’t any of these elements, they can be created. Doing this ignores a big difference: pornography sets the scene for fantasies and practices that aren't problematic in themselves, between consenting adults, but crime news concerns real assaults suffered by real people.

And so victims of violence suffer violence once again, from journalists who give them the leading role in a pornographic narrative - obviously without their consent.

Rape is almost never enough by itself. It’s not as though it’s comparable with ‘top drawer’ violent behaviour, such as murder (better if it’s multiple murders), paedophilia and, more recently, terrorism. When the statement of a sexual assault victim is reported, the close miss of a more tragic fate is always suggested. Did you fear for your life?, they ask. And so the headline becomes I was afraid to die.

A rape is a rape, but it easily becomes ‘just’ a rape. Or even an apparent, mythologized, instrumental rape, as can be seen when reading some of the Italian press on the ‘Weinstein case’, with dozens of male (and unfortunately a few female) commentators busy explaining to Asia Argento – and to the other female actors who publicly reported systematic sexual assaults by the film producer – that their rape wasn't actually a rape, but a simple exchange of sexual performances for career goals. A textbook case of mansplaining where on the front line, not by chance, were the same media already involved with the Ghersi case and capable of taking the argument to its vicious consequences: women are victims, but only if men grant them this status, especially if these unfortunate females demand to take the issue into the media. A male field, as Harvey Weinstein has always known.

Woe to anyone violating the gentlemen's agreement about the news coverage of sexual assaults, then. A rape needs two elements in order to aspire to an important place in the newsmaking chain:

- one within the narrative, such as savage brutality and some hardcore details

- one outside the narrative, such as the capacity to activate a macro frame like ‘out of control immigration’, ‘Islamic invasion’ or ‘the do-goodery of radical chic politics’.

The first element is represented with nauseating precision by the fake Giuseppina’s ‘panties still down’. Behind a dusting of pity morbid voyeurism looks out, for which the problem of the victim’s dignity does not arise and which uses the weapon of shame to mask the pleasure of looking at the private parts of a child's body, and from showing the image and sharing it virally. And the author isn't an isolated case.

Libero's (a right wing newspaper) report on the rape in Rimini focused from its very URL – which translates as ‘rape-sexual-violence-double-penetration-butungo-moroccan-polish-tourist-trans-peruvian’ - on detailed description of the abuse and which brought media sexual violence to a new level: those who've already suffered physical and psychological violence are forced to suffer more violence at the hands of the tabloid. More violence, virtually but no less invasive.

The second key element in sensational narrative about rape when applied to Giuseppina Ghersi's story is shown in the question ‘Did the partisans do it or perhaps a n****r?’ An apparently meaningless combination to be interpreted in the context of the short-circuiting between toxic narratives we have seen over the last few months. If three young men of Moroccan origin rape two people, ‘It's all Laura Boldrini's fault’ because she’s ‘a friend of the n*****s’, and therefore she should be raped as soon as possible; and organizations fighting against sexual violence on a daily basis, like the Non Una di Meno movement, are accused of a conspiracy of silence about rapes by immigrants.

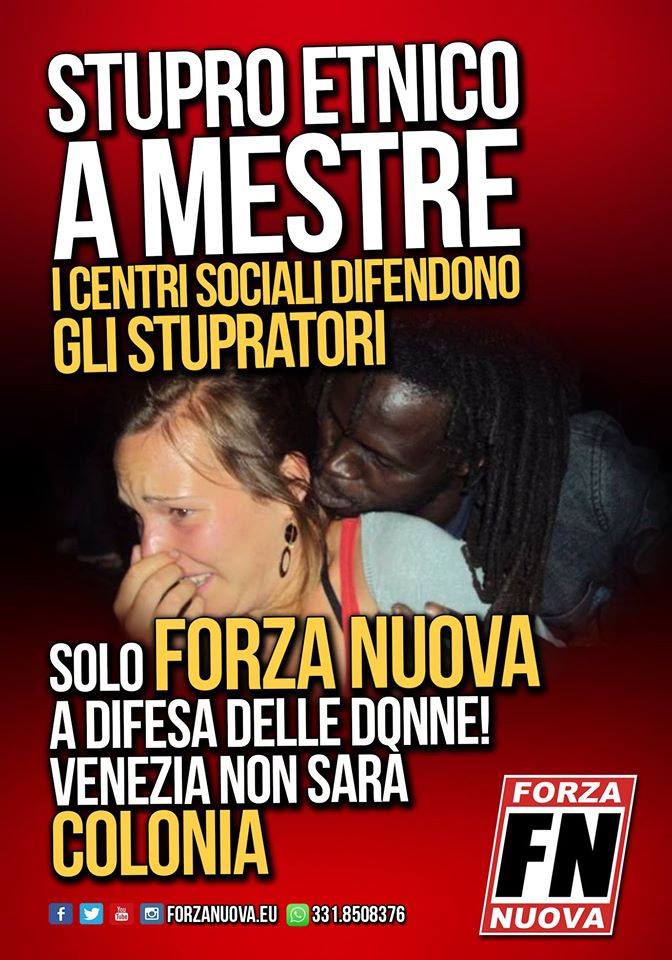

[The concentration of fake news in this poster is record-breaking even for fascist serial liars.]

Raped women become the target of a campaign combining sexism, racism, paternalism and delusions about security. If they drink and hang out in slums, they’re guilty of recklessness.

All right, but what is the connection between partisans and black people?

It’s the transitive property - or rather its delusional version. The ‘usual leftist do-gooders’ who keep quiet about rapes by immigrants are also silent about the faults of the Resistance. So if a rape is censored, the cause is to be found in a communist conspiracy to protect black people and partisans, and to despise real Italians.

4. Gender and violence in fascist war

Gender violence or sexual slavery are instruments of oppression and terror in every war, including fascist and Nazi war, even if the orders from above or racist ideologies do not explicitly say so. The use of rape as a war weapon by the Japanese army is documented plainly in the case of Nanchino (1937); it was employed widely by German troops and by the Wehrmacht’s auxiliary ‘Mongolian’ troops in Emilia Romagna in 1944 and by the Red Army entering Berlin in 1945; to say nothing of the violence perpetrated by the Allied troops, which has left an unforgotten mark, especially in central Italy. Rape is a weapon of war, a symbol of oppression and humiliation, a practice of male violence and an instrument for ethnic cleansing. It was only yesterday in historical terms (1992) that there were mass rapes of more than 25,000 Muslim Bosnian women by Serbian soldiers, part of a strategy of terror that was planned and managed from above with clear military orders.

The subject of sexual violence must therefore be framed within the more general question of violence in relation to specific ideological elements concerning sexuality or gender violence. Difficult knots to untangle.

In the Seventies, psychoanalyst, sociologist and culture critic Klaus Theweleit analysed diaries, memoirs, novels and testimonies by fascists, Nazis, reactionaries and right-wing military figures, written during the years of the attempted revolution in Germany (1918-1925). The result was an immensely important book, Männerphantasien (1977, published in English in 1987 by both Polity Press and University of Minnesota Press under the title Male Fantasies Vols 1-2).

Theweleit shows how enemy women were the real nightmare for fascists fighting against Spartacism and left-wing military groups. The Free Corps (Freikorps) saw Spartacist, socialist and proletarian women take part in the revolution, fight on the barricades and serve as nurses, and they were obsessed by them. Theweleit notes phobic traits regarding the figure of the ‘red nurse’ which turns into the ‘red whore’: for fascists, sexual services are among those enemy women give to the injured. Proletarian women are described as real Furies or bloodthirsty Amazons, hysterical, imagined naked, taking part in orgies with their ‘communist males’.

Against the ‘red nurse’ fascists set the ‘white nurse’, an ideal type of angelic and desexualized woman, lovingly assisting patriots without any ‘dirty’ thoughts. Theweleit describes this as a phantasmagorical image, generated by having seen women taking part in the revolution. He also connects it to heavily sexualized gender-driven discomfort, to the point of interpreting some homophile traits among German fascists as a consequence of misogyny. The experience of war and comradeship emerge as a kind of existential and sexual ‘retreat’ in the face of the ‘female threat’.

The transition from the imaginary level, associating nationalism and sexuality with the central category of ‘respectability’ (cf. G. Mosse, Nationalism and Sexuality), to the strictly historical-social level, is different. In Italy fascism worked systematically, through propaganda and social relations, to involve women in supporting the regime and to mobilise them within stereotyped frameworks and roles: domestic angels, mothers of the Nation, mothers of future warriors, mothers of the proud Italian race… Meanwhile, it opposed every form of women’s freedom that challenged those roles, even if their involvement in public life created some contradictions: the regime involuntarily created spaces where the woman became something more than the stereotype beloved of propaganda. The consequences would have been seen during the war and also in the Resistance, with the spread of the new ‘red nurses’; they were deviant characters anyway, connected to widespread sexual stereotypes, that must be considered trans-ideological and typical of the time.

Some specific traits of the right-wing mind and its world, particularly linked with the cultures of paramilitary violence, do not necessarily explain or clarify the real behaviour of soldiers, armed males, regarding gender violence. Jonathan Littell has taken up Theweleit’s work and used it for Les Bienveillantes (The Kindly Ones), a novel written from the point of view of a Nazi official involved in the war of extermination on the Eastern Front. Littell returns to this subject in the essay Le sec et l'humide: une brève incursion en territoire fasciste, using and extending the model of the ‘soldier-male’ to French and Americans, for example, but also to the ‘Islamic suicide terrorist’, the ‘Tamil or Chechen fighter’, the ‘Rwandan slaughterer’ and the ‘arm cutter of Sierra Leone’. However, he clarifies:

It seems clear to me that a man driven by his psyche to voluntarily join an organized group committed to extreme violence [...] is not in the same situation as millions of soldiers of modern mass wars.

According to Sandra Newman (in D-Repubblica, September 30, 2017, p. 84), comparative studies show that sexual violence is:

historically rare among left-wing guerrilla militants. In 1981, in Salvador, after a 12-year civil war, a report by the Truth Commission of the United Nations did not find a single case of reported rape committed by the rebels, while rapes by government forces were common during the first years of conflict.

5. And what about during the Italian Liberation War?

This does not mean that violence against women by members of partisan groups in Italy does not exist.

From the scarce sources available, it appears to have been not only the action of a minority, but also a forbidden, discouraged and punishable event.

To avoid any simplification, it is useful, today more than ever, to place the issue in a more general framework of war against women in a context of widespread anomie, where the gender issue intersects with total war and civil war and war against civilians. It should not be forgotten that documents and memories regarding violence against women are hard to bring to light. That is because the oppression of women is a widespread phenomenon in every society and in every war, and victims face understandable difficulties in making a complaint.

A first element to consider in general terms is the ethical and behavioural consequences of a liberation army commanded by former officials and volunteer militants which has the objective of establishing a new political legitimacy. In pragmatic terms, the success of a guerrilla war depends on a good relationship with the local community and on being rooted in the territory. Hence the attention and strictness with which the commanders followed all relations between guerrilla members and the population, in the different phases of the 20-month Liberation struggle.

We must start from the exercise of violence by the partisans: the necessary and reactive violence by the insurgents during the phase of reorganization compared with the structural violence of Nazis and fascists. That is to say a regular army compared with an armed party within a totalitarian regime in Europe, a continent occupied and torn apart by years of war.

In his book Una guerra civile. Saggio storico sulla moralità nella Resistenza (“A civil war. Essay on morality in the Resistance”, chapter 7, p. 413-514) Claudio Pavone analyzes in depth the wider issue of violence on both sides. Pavone focuses particularly on the more of violence:

That ‘more’ of which all veterans of every war do not want to talk. It is not enough to say that cruel and sadistic fighters are to be found on any side and to conclude that, in fact, there are incomparably more on the fascist side. Instead, we have to look at the basic cultural structures supporting the two sides, to ask ourselves why one party is better suited to select cruel and sadistic members and to make the darkest impulses of human soul emerge clearly as political acts

(p. 427).

As Giovanni de Luna points out:

In civil wars an excess of horror, a surplus of violence disconnected to the immediate goals of the fight is always implicit. It’s not enough to declare the other as enemy for Italians (or Spanish, French…) to start killing each other: you must deny in the other first the brother, then the man, relegating him to the status of animal. It’s this overflowing of terror and brutality that is the root cause of a collective repression that leads to the removal of civil wars from history, hiding them behind shields of words.

(La Resistenza perfetta, 2015, p. 157)

For fascists, the public killing of partisans and displaying their bodies was part of a strategy whose overall meaning was independent of the purely military aims of the war. It was about inflicting a double death on their enemies, killing their bodies twice: ‘The outlaw dies twice, firstly by firing squad, secondly by hanging, or hanging twice, so that his killers can capitalize on his death, terrorising those many who live with just one who has died’. (Santo Peli, La morte profanata, ‘The desecrated death, in Protagonisti, no. 53, 1993, p. 41).

[Bassano del grappa, September 26, 1944. The bodies of 31 partisans along the city’s riverfront. A sign reading ‘BANDIT’ hangs around each person’s neck. The 31, some under pressure from their family and/or their priest, had answered an invitation from the German command: turn yourself in, save your life and there will be no retaliation on your families. Instead, they were taken to the riverfront and hanged with phone wires, so that death would not be immediate. They remained in plain view of the inhabitants for four never-ending days. The slaughter was part of the broader ‘Operation Piave’, during which the nazifascists killed 263 people just a few days.]

As De Luna emphasises:

During the partisan struggle one kills, but almost always because it was the only choice, without giving the bloody violence a liberating value, without celebrating ‘violence as violence’, without making any concession to a kind of intrinsic value of violence [...] When from documents and witness statements a partisan emerges who kills easily (or even with pleasure), it arouses admiration or discomfort, enthusiasm or perplexity in his companions but it is never accepted as something obvious or taken for granted

. (La Resistenza perfetta, p. 16).

What’s more, among the partisans, the problem of excessive use of violence was seen as a sign of lack of soundness in political education. Without a proper education and in emergency circumstances, with the increase in members at certain times, it was also crucial to avoid the risk of fighters starting to behave as thrill-seekers: hence the harsh punishments, and the division and brigade tribunals, which had the dual purpose of maintaining discipline and leaving the Resistance movement - described by the new fascist collaborationist regime as composed of bandits - spotless in the eyes of the population.

It was Arrigo Boldrini, the famous partisan commander ‘Bullow’, who pointed out later, in 1945, the lack of discipline and impatience with authority of many young members of the base of the Resistance: ‘uneducated’ factory workers and farmers, who only had ‘willingness and awareness’. Ferdinando Mautino remembered that ‘discipline wasn’t imposed but requested’, to the point where the death sentence was requested by whole formations for comrades accused of serious shortcomings, in the need for law (see Pavone, Una guerra civile, p. 457).

Then there were the serious logistical problems that characterise guerrilla war by comparison with war waged by regular state armies: what to do with spies? And what about deserters, common criminals and prisoners? The issue could be solved with prisons but that is not possible for a guerrilla army constantly on the move in a territory occupied by an organized enemy. So there were only two options: acquittal or death. The question of judgments made in an emergency situation, with the associated risk of ruining entire groups of fighters, is very concerning.

De Luna mentions an incident in March 1945 in Piedmont, in an area where fascist repression was very strong, that shows a real psychosis towards spies. It involved two young women, Lucia B. (21 years old) and Caterina R. (22 years old) who were ‘escorted to the fields called Pra ‘d Rioca Vaca, just in front of the Barge graveyard, robbed (of their shoes, a watch and two bags), shot and buried in secret by two partisans commanded by ‘Moretta” (pp. 172-173). In two other cases in the area women had been executed as suspected spies. In this case, though, the accusations were vague and concerned alleged ‘relations with nazifascists and making advances to the partisans’, essentially being on good terms with both the nazifascist establishment and the partisans. The event was extremely controversial and produced strong reactions from other commanders because the decision had been taken ‘without unequivocal evidence and rigorous investigation’. As a consequence, there were public apologies, a poster was produced and compensation was paid to the families of the victims. Moretta, considered a ‘dangerous fool’, was tried by the divisional headquarters for the murder of the two girls, demoted and moved to another detachment, avoiding the firing squad only thanks to his previous good conduct as a partisan. He was to die after the war, before the end of the trial against him for giving these orders.

In addition to military violence, historiography has not escaped the difficult and controversial subject of the ‘settling of accounts’. Again and again, the revisionist, anti-Resistance interpretation of this topic makes the context impossible to understand. This was a mixture of justice and vengeance, with the partisans more concerned with limiting and controlling structural and widespread violence and the thirst for popular revenge than with exercising it. And it’s always wrong to judge violence decades later, without understanding what it means to still be in a civil, total, war of occupation and retaliation. Just as every argument about the Resistance must begin with the nub of the choice to openly challenge Germans and fascists with weapons, the topic of violence cannot be separated from its background of the war and the extreme circumstances, and from the reasons for and goals of that violence, that is, the project of a future society.

Another issue is sexual violence against women and here we must take into account - and this cannot be stressed enough - the victims’ silence and the difficulty in finding sources. Michela Ponzani in Guerra alle donne. Partigiane, vittime di stupro «amanti del nemico» 1940-1945 (War on women. Partisans, rape victims, ‘lovers of the enemy’ 1940-1945), focuses her analysis on abuses suffered by women in different locations, in the home, in camps, in different places in the Republic of Salò. Her study shows how nazifascist violence carried out against women had the double function of gathering information and of punishing women stepping out of their traditional and subordinate roles of wives, mothers, daughters and sisters. A decisive factor appears to be:

The military-masculine culture of the “perpetrators”, their psychology, their educational background pushing them to punish women who dared to rebel against the regime and who wanted to fight to emancipate themselves from that inferior role in society.

(p. 172)

Testimonies show differences among the partisans regarding the issue of violence:

In the Garibaldi brigade Nino Bixio, fighting in Liguria, over a few days two partisans were executed for sexual violence and robbery, one for theft, one for robbery, one for being ‘a robber, a thief and a spy’ (mentioned in reports October 1-4 1944, in Pavone, Una guerra civile, p. 455).

Nuto Revelli in La guerra dei poveri (“The war of the poor”) reports the order concerning a spy:

Don’t beat her, don’t touch her. We aren’t fascists: no torture, no vulgarity. We’ll shoot her.

(p. 199; note of April 16 1944, in Pavone, Una guerra civile, p. 417)

Considering the difficulties of making facts emerge from the past, as in the Ghersi case, it does not mean that violence against fascist women or sisters of fascists did not happen. In Guerra alle donne Ponzani, through direct testimonies of women who lived through the Second World War, also describes post-Liberation violence (pp. 253-282). The ‘lovers of the enemy’ had their hair shaved, were painted red, taken around the city, mocked, beaten, insulted. Accused of having had real and/or alleged relations with Germans and fascists, out of envy or slander, they are hated, eccentric and unacceptable figures for the social, moralistic and patriotic standards built around idealized female models. Female collaborators are described as ‘unfeminine’: loving luxury, of dubious morality, looking like ‘tigers’, dressed in men’s clothing; their behaviour is deviant, dishonorable, lascivious. Wearing pyjamas and smoking, they witness partisans being executed, like Maria C who was accused of having five partisans of the Garibaldi brigades of Como captured. In some places (there are mostly testimonies from Piedmont in the book), court work had to be speeded up to avoid summary justice.

Public lynching and hair shaving, in their violent erasing of the symbol of femininity, are a typical feature of the ‘male’ war ritual; [...] a form of exemplary punishment, inflicted on those women who have betrayed their own national community of origin (p. 263).

In an episode in Milan reported by Ponzani, a group of ‘last minute partisans’ wanted to shave the hair of two fascist sisters after they had returned home. As one was underage and pregnant, another sister who had stayed at home offered herself in her place. Those ‘partisans’ shave her hair, even though she was not directly accountable. This is an example of ‘ambiguous and cowardly behaviour, of confused choices’ for which ‘there is [...] no reason linked to being accountable for having supported the fascist regime’ (pp. 262-263).

They are tragic, often very young female characters, like Santina in La luna e i falò (The Moon and the Bonfires by Cesare Pavese), the beautiful young daughter of the ‘boss’, close to the fascists and who infiltrated herself as a spy among the partisans, whose burnt body ends the book and whose image is a focus of the contradictions of civil war. They must be viewed as victims of bad education, of propaganda and of their own femininity, lived, exhibited or used in a context where life and survival are at stake. On the edge of a world of violence and glances, and also marked by patriarchy.

- End of Part 1 - The original article in Italian is published on Wu Ming Foundation's website Giap.

Comments