In the last eight years we have seen a multitude of struggles: from hunger strikes to riots, from work stoppages in individual units to mass strikes across several prisons, from hostile gangs forming truces and challenging racial divisions to immigrant mothers (incarcerated with their children) refusing their meals and duties. Published by Houston Incarcerated Workers Organizing Committee and Unity & Struggle.

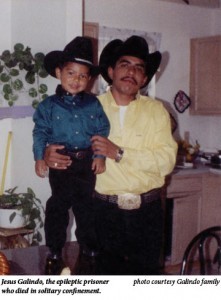

Jesus Manuel Galindo, 11.29.1976 – 12.12.20081

The Houston Incarcerated Workers Organizing Committee (I.W.O.C.) would like to dedicate this pamphlet to the memory of Jesus Manuel Galindo, a detainee at the Reeves County Detention Complex in Pecos, Texas. His death was not in vain.

Introduction

The following summary was completed on the heels of the Texas work stoppage, a mass strike taking place in April of this year, but the idea for it came out of discussions two years prior after a series of hunger and labor strikes spread across the US. These strikes occurred in both private and public facilities – in prisons that housed primarily US-born workers and also detention centers responsible for the incarceration of undocumented workers and even families.

We are writing this for you–our fellow workers locked down and forgotten by mainstream society–and for us, since we know our own struggles against the bosses and the State on the outside are inseparably tied together with your struggles. Living in the country with the largest prison population in the world, many of us have family, friends, and comrades who are already incarcerated. We know that where you are is where we are all headed unless we organize and fight back.

In the last eight years we have seen a multitude of struggles: from hunger strikes to riots, from work stoppages in individual units to mass strikes across several prisons, from hostile gangs forming truces and challenging racial divisions to immigrant mothers (incarcerated with their children) refusing their meals and duties. As we will explain here, Texas, and the South generally, has been virtually at the forefront of every prison struggle in the last decade.

The mass strike that occurred among seven facilities in Texas in April 2016 is a benchmark in the development of a prison movement that we have identified as beginning in 2014, but with significant struggles occurring in fits and starts since 2008 beginning with the riot in Pecos, Texas. Most of the events documented here took place without each prison knowing about other prisons’ actions or prior events, representing one of the logistical and organizational challenges of this movement, but where awareness of other actions did exist, it created a wildfire of activity and a continuum of struggle that is not always present. Our hope is that by sharing this summary of the series of prison struggles that have occurred in the last eight years, you will be as inspired as we are to continue the fight and, in the short-term, prepare for a nationwide prison general strike on September 9, 20162 .

“Motin,” the Opening Shot

He would sing love songs to his worrying mother over the phone to calm her nerves. She knew Jesus was epileptic. In fact, she was so concerned that she called the warden, but was reassured by prison officials that her son would be well taken care of in the Special Housing Unit (SHU).

They called it “la celda de castigo,” the cell of punishment. It was standard practice for inmates who complained about the lack of medical aid to be placed there. Jesus complained. And instead of getting the attention that was promised to his mother, he was locked up in a dungeon and forgotten. He had legitimate cause for concern and wrote in a letter to his family that he was worried he would not get the epilepsy treatment he needed, putting him at grave risk. The phone call never came and it was only when Jesus’ mother called to check on her son was she told that Jesus had died.

He was dead long enough that when they finally checked on him, his body was stiff and purple.

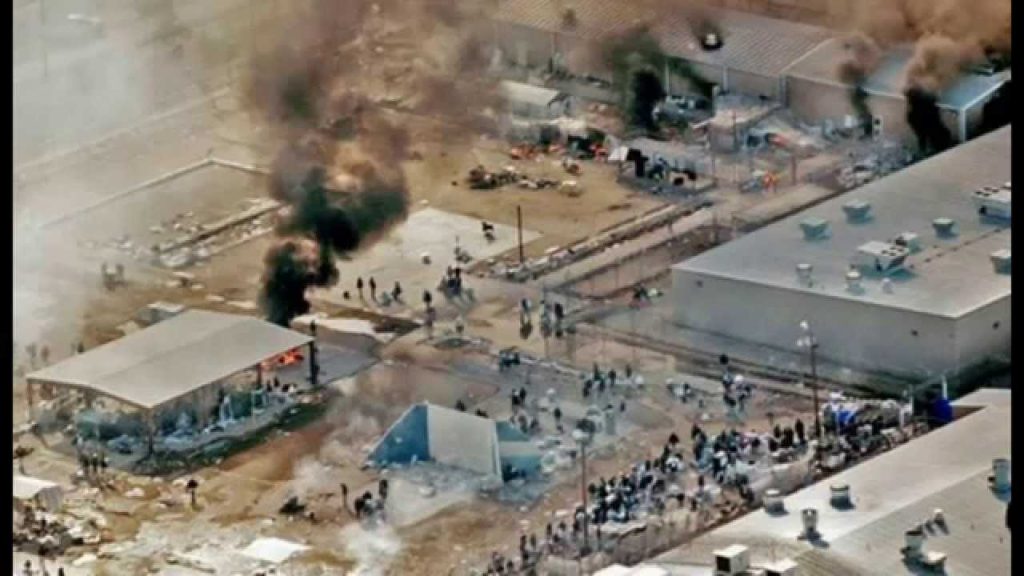

Jesus Manuel Galindo was refused medical treatment due to his epilepsy and left to die, and while this might have been a typical occurrence at any detention center, what wasn’t typical was the response. The Pecos Insurrection, or “Motin3 ,” as it was called by its participants, was the second revolt in a matter of weeks. The insurrection took place from December 2008 to January 2009 at the Reeves County Detention Complex, which is owned by the GEO Group. Several hundred detainees responded to Jesus’ death by executing a daring takeover of the facility, setting it ablaze and inflicting over $20 million worth of damage4 .

“By midafternoon, members of the FBI, Texas Rangers, DPS and the Odessa Police Department arrived at the prison. As the crisis negotiators quickly found out, the riot had not been prompted by gang infighting, racial tensions or a spontaneous outburst of violence. The men incarcerated at the Pecos prison are considered ‘low-security’; most are serving relatively short sentences for immigration violations or drug offenses.”

Detainees take control of Reeves County Detention Complex in Pecos, TX, Jan. 2009

The rebellion brought together workers of many nationalities and races, and created a detainee delegation composed of Venezolanos, Nigerians, Cubanos, and Mexicanos who negotiated for changes in food, healthcare, and legal resources at the facility5 .

The opening shot of the prison movement was powerful, and although little was said about in the media, there can be no doubt that it will remain a reference point for the State on the weakness of its rule and the humanity of those it holds in bondage.

“Crips, Bloods, Mexicans Together”: 2010-2013

Two years later, in December 2010, a tenfold-unit mass strike, the largest prison strike in US history6 , rocked Georgia as thousands of incarcerated workers refused to leave their cells in protest of unpaid labor (the standard in Georgia). Inmates of all kinds – black, white, and Latino, crips and bloods, Muslims, and Aryans7 – were able to coordinate with each other across units using contraband cellphones. Among the facilities that participated in the strike were Augusta, Baldwin, Calhoun, Hancock, Hays, Macon, Rogers, Smith, Telfair, Valdosta, and Ware. Collectively, they demanded wages for their work, while also putting forward demands concerning education, communication with family, meals, parole, and ending solitary confinement. However, the strike was brutally repressed by the Department of Corrections (DOC) using lockdowns, beatings, and transferring the leadership of the strike which resulted in a decrease of activity for the next year.

Georgia incarcerated workers on strike, Dec. 2010

In June 2012, activity in Georgia found new life with a hunger strike at Jackson State Prison. Jackson was the same facility that once housed Troy Davis, an innocent black man put to death by the State, which resulted in thousands of protesters in the streets. This is where the leaders of the mass strike were transferred and, along with dozens of other inmates, held a hunger strike.8 Significantly, a group of students and activists in the free world, many of which had taken part in the Troy Davis demonstrations, organized actions on the outside including clogging up DOC phone lines and marching on the DOC offices in Atlanta. The strike lasted 44 days and saw many men on the verge of death and as they faced retaliation by prison officials and their goons. A delegation of nearly 100 supporters traveled to Forsyth to meet with Commissioner Brian Owens to pressure him into granting the strikers demands but he refused to see them. The strike was defeated but the legacy of December 2010 lives on as incarcerated workers continue to organize under the banner of United Nations Against the Machine.9 The most important variable was the convergence of militant actions on the outside by supporters, adding new weight to and raising the stakes for prisoners’ activity.

Organizing across race and gang affiliation would find expression again in perhaps the largest hunger strike in recorded history which took place in July of 2013, at the Pelican Bay State Prison, the only supermax facility in California10 . The hunger strike was organized by an unlikely alliance of gang leadership, which was comprised of the Aryan Brotherhood, Black Guerilla Family, the Mexican Mafia, and Nuestra Familia and involved 30,000 participants. Ironically, if it weren’t for the SHU, this strike might have never happened, but because the gangs’ leaders were all housed there, they began to communicate and even discuss radical political literature explaining their conditions. Some of that literature included the Bible.

“[Sitawa] Jamaa [leader of the BGF] thought his fellow inmates might need some concrete encouragement. His private fast the previous fall had lasted 33 days, and he believed he could have gone longer. Soon after last summer’s strike began, the four leaders were moved from the SHU to a unit called Administrative Segregation, and Jamaa, entering the unit, started to holler, “Forty days and 40 nights! Forty days and 40 nights!” If prisoners can be counted upon to know any literature, it is the literature of suffering that in the Bible precedes redemption. Jamaa had chosen his slogan with intent: They were Moses in the desert. At night, Jamaa would drop on his knees, put his mouth to the crack between the door and the floor, and yell: “Forty days and 40 nights!” Soon, new hunger strikers arriving in AdSeg were shouting the slogan as they were hustled in. It was then that Jamaa began to believe their movement had some possibility, some momentum.”

There is some question as to how voluntary this strike was and it is possible that at least some of its participation was due to compulsion from the gang leadership. Whatever the case may be, 30,000 men realized their collective power that they could continue to wield for themselves. As a result of their activity, the State of California moved thousands of incarcerated out of solitary confinement, effectively ending its use.

Galindo Lives: Immigrants Strike Back Again at GEO Group, 2014

On March 11, 2014, only nine months following the hunger strike at Pelican Bay, and likely without any knowledge of its existence, a massive hunger strike was declared at Northwest Detention Center in Tacoma, Washington involving all 1200 of its detainees. Like the Reeves Complex in Pecos, Northwest is also run by the GEO Group. Hundreds of supporters rallied in front of the NWDC complex followed by a series of actions involving more than 500 protesters, including one at the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, calling for their divestment from GEO Group stock holdings. The hunger strike carried on for a total of 56 days. Following this two-month-long effort were two more abortive strikes in August and November.

Word of the initial Tacoma strike spread from its Pacific Northwest origins to the Gulf Coast and the border as detainees held at Joe Corley Detention Center in Conroe, Texas (another GEO enterprise) also refused their meals.

“Inspired by the Tacoma strike, inmates at the Joe Corley Facility decided to carry out their own hunger strike in Conroe. Initial reports were that a larger group had started the strike but that the group had become smaller by the time they released a demand letter through a lawyer. Similar to the strikers in Tacoma, Joe Corley inmates demanded improved conditions of the detention center, better quality of food, outdoor privileges, and better visitation arrangements. But unlike Tacoma, they demanded something quite different: the abolition of deportation and detention.”

In fact, they refused to leave their cells in what amounted to a de facto labor strike that brought the maintenance of the facility to a standstill. Additionally, like the Jackson, Georgia hunger strike two years prior, a group of immigrant activists in the free world met with key organizers of the hunger strike to coordinate actions on the inside of Corley in concert with actions on the outside against liable political targets – in this case, Sheriff Adrian Garcia11 . Garcia was an ardent supporter of 287g, or “Secure Communities”, which allows police to coordinate with Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) and effectively turning cops into border agents. The activists stormed the Sheriff’s office with 100 in tow delivering the demands of the strikers. While plans for a second strike were made, they did not materialize due to the transfer or deportation of its strike leadership. But while Corley officially stomped the flames of resistance, they unwittingly spread its embers as its participants carrying the lessons of the Corley strike with them in their hearts.

Activists and family of hunger strikers storm Sheriff Adrian Garcia’s office in Houston, TX, Apr. 2014

At nearly every stage of struggle, a new leap is made in tactics, breadth, militancy, organization, and consciousness. The hunger strike wave of 2014 is has important implications: it is the first identifiable strike wave, where one strike inspired another; strikes occurred at facilities owned by the same master, the GEO Group, which has important strategic implications; and finally, the demand became one for abolition of deportation instead of its reform.

Free Alabama Movement and the Industrial Workers of the World

While detention centers are being rocked by immigrants holding hunger and labor strikes, a labor strike was called for in advance by the Free Alabama Movement, or F.A.M.12 The first strike, in January of 2014, began with two facilities, St. Clair and Holman, and grew to include two more units13 . One of its leaders, Melvin Ray, learned about the Georgia mass strike in 2010 and was inspired to organize a similar effort in his home state.14 There was little attention given to the January strike but it was organized, like its Georgia predecessor, against unpaid labor as Melvin said the State of Alabama was “running a slave empire” and “incarcerating people for free labor.” Sadly, the second strike in April was preempted by prison authorities and although it never took off, it nevertheless resulted in a relationship with the Industrial Workers of the World15 , a radical union with a history of organizing on the margins of society. The IWOC, an IWW committee, emerged from the interactions with F.A.M. organizers.

Melvin was interviewed in December 2015 about current efforts at organizing and networking with other prisons:

“At the forefront of our Movement is networking with prisoners around the country and expanding the freedom movement against mass incarceration and prison slavery. To date, we have linked up with UNAM (United Nations Against the Machine) who are the prisoners in Georgia that organized the shutdown in 2010, we helped the prisoners in Mississippi to form the Free Mississippi Movement United, The New Underground Movement (brothers in the California prison system), brothers in the Kansas prison system and Iman Siddique Hasan of the Lucasville 5 in Ohio’s prison system.”

Back in Georgia two months later in June, this time at an immigrant detention center in Lumpkin, hundreds of detainees went on hunger strike tossing their food, known to be contaminated and rotten, into the garbage.17 This was a blip in the media and information around it is wanting.

The Era of Riots, 2015–present

The year 2015 had some important developments worth noting and shows that all tactics are still on the table whether they are hunger strikes, labor strikes, or riots, but it was this latter form that predominated.

The new year was touched off with a riot at the Willacy County Detention Center in Raymondville, Texas near the Mexican border. Just like the “Motin” in Pecos, the riots were a response to inadequate housing and medical conditions. Willacy, run by the corporation MTC, was an overcrowded tent facility and was declared “uninhabitable” by the time the detainees were done burning it down and compelling their transfer to alternative units.18 Also like Pecos, there were no reported fights among the detainees; they stood united against MTC, the guards, and the police with a bravery like no other. The politics of this riot were implied in its destruction. Detention centers and prisons should not exist, and to this day Willacy exists only in history.

Smoke emanating from the now non-existent Willacy Detention Center in Raymondville, TX, Feb. 2015

In April of that year there were two back-to-back hunger strikes that took place in another GEO Group facility19 , this time a family detention center reserved for immigrants in Karnes City, Texas. A group of mothers incarcerated with their children not only refused their meals but also the voluntary duties that came with a $3/day wage.20

A planned labor stoppage turned into a riot at a state prison in Tecumseh, Nebraska the following month, after prison officials received a demand letter backed with the promise to strike.21 An informal committee at Tecumseh came together to draw up a set of demands and present them to prison staff. If the demands were not met, the following day the work would stop. The day of the demand delivery several dozen committee members and supporters congregated in the main compound area and were ordered by prison staff to disperse. When the demands were handed over, the guards became aggressive and began to pepper spray the group and several started fighting back. An incarcerated member of the IWW who took part in the resistance wrote a reflection on the events:

“The group stood as one and began marching around the compound. Inmates inside the housing units joined in at this time. Staff ran for cover, locking everyone out of their housing units. The group of inmates marching on the compound tried to break into the gym to let out inmates who had been locked in.”

Eventually, the authorities retook control but the news of this strike was reprinted in the Industrial Worker (the I.W.W. press) and shared with other incarcerated workers across the country who will no doubt find inspiration from this brave standoff.

Another hunger strike was organized in Arizona in June23 and included 200 detainees at Eloy Detention Center owned by Corrections Corporation of America who owns multiple detention centers in Texas, Oklahoma, Georgia, Tennessee, Colorado, among other states24 . The strike came together after guards brutally beat and placed in solitary confinement José de Jesús Deniz-Sahagún who later died of his injuries.

“At 9:45 a.m., the men sat down in the recreation yard and declared a hunger strike over what they call brutal and inhumane conditions, according to grassroots justice organization Puente Arizona. Protesters stood outside the detention facility all day Saturday, holding signs to show their solidarity with the strikers.

“The group said it is demanding improved conditions, access to legal resources and court hearings and an independent investigation into two recent deaths after what it calls ‘guard abuse.’

“The detainees also say they want an end to exploitation of their work and ‘no more criminalization, detention and deportations.’”

Here again the militant call for the end of detention and deportation supersedes demands for reform.

All was quiet for the remainder of 2015, when in March of 2016, a violent episode transpired back in Alabama at the Holman unit. This time, instead of striking, prisoners were burning the place down.27 The initial context was the arrival of the new warden, Carter F. Davenport, who formerly ran the St. Clair unit. During his tenure there, he oversaw a 200 percent spike in violence in a facility that had a record for the lowest incidences in violence. This is partly due to his cutting of popular programming. He is known for personally taking part in the violent abuse of prisoners. Now he was given a taste of his own medicine.

“‘Two inmates got in a fight, and 30 minutes later, the C.O. comes in yelling, disrespecting everyone, tearing a bunch of guys’ shit up, guys that got nothing to do with it,’ Poetik told The Daily Beast. An ‘elder’ inmate, a long-timer who has built a rapport with staff, stepped in to calm things down, Poetik said.

“‘The officer did not wanna hear that shit, and he started yelling and cussing at him, and that’s when the stabbing started.’

“Poetik said Warden Davenport ‘came down with the same attitude, cussing this guy out—so then it was no more talking, and he got stabbed.’”

Early in the morning on March 12, prisoners took over dorm “C” and began destroying their cages with fires and destruction. They organized their efforts through contraband phones, just as in Georgia in 2010, and took videos of their wrath.28 Prisoners held Holman for nearly four hours before the authorities regained control. The following weekend F.A.M. members sent a list of demands to Alabama D.O.C. for “immediate federal assistance” and a repeal to repeat offender laws among others.

Texas Work Stoppage of 2016

Finally, we reach the most recent and one of the most advanced episodes in the last eight years of prison resistance; a mass strike organized by IWW members on the inside. Starting on April 4th and then spreading, incarcerated workers in seven units, including Lynaugh in Fort Stockton, Mountain View in Gatesville, Polunksy in Livingston, Roach in Childress, Robertson in Abilene, Torres in Hondo, and Wynne in Hunstville refused to be called out for work.29

At the Robertson unit, an inside report was received from an IWW delegate that the authorities tried to preempt the strike by going on lockdown on the evening of April 3rd. But on the morning of the 5th, when calling out prisoners to work, with the exception of the trustees, the workers refused. This was the first unit-wide lockdown in eight years and it put a lot of pressure on the staff to carry out tasks done by incarcerated workers. The prison officials attempted to divide the unit by rewarding the strikebreakers with fresh clothes, meals, and commissary, while the strikers were given tasteless and non-nutritional “johnnies,” soy beef loaf and PBJs. The unit went off lockdown on the 22nd and most returned to work, but not before costing the unit three weeks worth of lost labor time.30

The incarcerated IWW group in the Robertson unit, with the conclusion of the work stoppage, are currently regrouping, drawing on tactical and organizational lessons, and carrying out a slowdown of work in preparation for a nationwide general strike set to happen on September 9th, the 45th anniversary of the Attica Uprising of 1971.

Conclusion

The Industrial Workers of the World (I.W.W.), or “Wobblies”, has a more than century-long reputation of organizing the working class as it exists in every skin or body, nationality, skill-level, and industry. It was the first union organized by immigrants, blacks, women, unskilled workers, prisoners, and everyone else who the official mainstream labor organizations refused to organize and often sold out. Instead of relying on the law, the courts, and politicians, all of which are complicit in the mass incarceration of our class, we use our own collective and direct action, experience, and organization to not only fight for immediate demands, for an long-term improvement in conditions for ourselves. Our vision is for a world without a wage system, without prisons, and without capitalism and a division of labor which stamps us as specific types of workers with a specific values that alienates us from our own humanity.

The I.W.O.C. is a committee of the I.W.W. that emerged following the Alabama strike in 2014. The I.W.O.C. “functions as a liaison for prisoners to organize each other, unionize, and build solid bridges between prisoners on the inside and fellow workers on the outside.”31 We are small but dedicated, and our impact is larger than our numbers. We are not paid staff members. We are workers, who, when not organizing on the job, must organize in our off-hours.

In Houston, as well as in Austin and Dallas, we are a liaison for prisoners in the state of Texas and we have a history of organizing with prisoners and detainees. We and our broader networks intervened directly in the Joe Corley strike, helped coordinate with striking detainees for inside action, and mobilized our own networks to act as pressure points on the outside. We stood against ICE raids and the detention of undocumented fellow workers, and we marched directly on the Harris County jail. We are ready to stand today and to whatever we can to ensure that you are not alone.

You are in there for us, we are out here for you.

For more information contact us at:

Houston I.W.O.C., PO Box 540662, Houston, TX 77254

832.930.1905

- 1https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=HGhHtFpAkRw

- 2https://theintercept.com/2016/04/04/prisoners-in-multiple-states-call-for-strikes-to-protest-forced-labor/

- 3https://www.texasobserver.org/the-pecos-insurrection/

- 4https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=mPYaB86iK3Q

- 5https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ym1EMULz6do

- 6http://www.deathandtaxesmag.com/41235/the-largest-prison-strike-in-american-history-goes-ignored-by-us-media/

- 7https://www.wsws.org/en/articles/2010/12/geor-d13.html

- 8http://onlineathens.com/stories/091711/new_886867250.shtml#.VyPk3kck960

- 9http://www.atlblackcross.org/index.php/2015/12/10/united-nations-against-the-machine/

- 10http://nymag.com/news/features/solitary-secure-housing-units-2014-2

- 11http://unityandstruggle.org/2015/08/18/the-conroe-detention-center-strike-reflections-of-a-houston-militant-and-wob/

- 12http://www.salon.com/2014/04/18/exclusive_prison_inmates_to_strike_in_alabama_declare_they%E2%80%99re_running_a_slave_empire/

- 13https://web.archive.org/web/20140119135730/http://alreporter.com/in-case-you-missed-it-2/5571-alabama-prisoners-strike-continues.html

- 14http://www.truth-out.org/news/item/33974-challenging-the-prisons-an-interview-with-the-free-alabama-movement

- 15http://inthesetimes.com/prison-complex/entry/16607/alabama_prisoners

- 16ibid.

- 17http://www.acluga.org/news/2014/06/19/worsened-conditions-stewart-led-hunger-strike-last-week

- 18https://www.rt.com/usa/234471-texas-uninhabitable-prison-riot/

- 19http://www.geogroup.com/maps/locationdetails/23

- 20http://www.huffingtonpost.com/2015/04/14/detention-center-hunger-strike_n_7064532.html

- 21https://itsgoingdown.org/incarcerated-workers-uprising-in-nebraska/

- 22ibid.

- 23http://www.huffingtonpost.com/2015/06/13/eloy-hunger-strike_n_7577154.html

- 24https://www.cca.com/locations

- 25http://www.cbs5az.com/story/29312788/200-detainees-stage-hunger-strike-at-eloy-detention-center

- 26Emphasis ours, Houston IWOC

- 27http://www.thedailybeast.com/articles/2016/03/21/alabama-prisoners-use-secret-cell-phones-to-protest-and-riot.html

- 28https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=A1wf2JwV3Yw

- 29http://www.austinchronicle.com/daily/news/2016-04-06/texas-inmates-strike-for-better-conditions/

- 30At the time of writing we are still receiving updates from other units and prisoners about the results of the strike. In a future version of this pamphlet we can share those details.

- 31https://incarceratedworkers.org/about - (this page has been rewritten since the pamphlet was first published, so that exact quote is no longer there, but the spirit remains the same - ed.)

Comments