An interview with Lucasville Uprising prisoner Bomani Shakur/Keith LaMar, carried out by JR Valrey for Block Report Radio. This transcript was first published by the San Francisco Bay View.

Today our guest on Block Report Radio is Bomani, formally known as Keith LaMar. He is an Ohio death row political prisoner and survivor of the Lucasville Rebellion 23 years ago. He will talk to us about the history of that rebellion, his recent hunger strike, the state of Ohio planning to set his execution date and more.

M.O.I. JR: It’s on honor to have you on, my brother. Can you tell the people about the Lucasville Rebellion?

Bomani Shakur, smiling despite the shackles, sends this wisdom from death row: “It’s not really about whether or not you get killed; it’s about whether you had the courage to stand up and live.”

Bomani: A little over 23 years ago at the prison in Lucasville, Southern Ohio Correctional Facility in southern Ohio, and the Muslim prisoners were having a dispute or discrepancy with the warden over their administering of Tuberculosis tests. Apparently the tests that they were using contained phenol, which is an alcoholic substance.

Based on the Islamic doctrine, the Muslims, particularly the Sunni Muslims, are prohibited from ingesting this chemical, and so they tried to meet with the warden to come up with alternative ways to determine whether or not they had TB. And the warden of the time, a guy named Arthur Tate, a real hard liner, decided to press their hand and refused to give them an alternative. And so the Muslims started what they expected to be a peaceful protest to try to garner out that attention and hopefully pressure the administration to give them alternatives.

At the time, back in 1993 – this was before Mike Brown, before Eric Garner, before this public unrest and what not – racism was very rampant down at the penitentiary. Guys were being beaten, bullied and moved from here to there. So when Muslims took over the prison, took keys and unlocked doors, you know, they unleashed years and years of pent up rage. Things very quickly got out of hand, ultimately ended with nine inmates being killed, one guard being murdered.

And that brought down the weight of the state on all us. Guys who even had any kind of radical leanings were basically put front and center, used as scapegoats to send a message throughout the system for anybody who thinking about rebellion, thinking about going against the administration.

Guys were singled out whether or not they had anything to do with the riot. Anybody who was considered strong politically, physically or whatever inside the prison, guys were singled out, basically made examples of. I was one of those guys. They came to me…

[Automated Voice: This call is originating from an Ohio correctional facility and may be recorded and monitored.]

Bomani: I was 23 at the time. They wanted me to cop out, wanted me to become an informant, because the block where all the snitches were allegedly murdered was the block that I happened to be assigned to by the administration. That was the pod that I lived in at the time.

And so they suspected that I knew more than I divulged, and so they wanted me to become an informant. I refused. They wanted me to accept a deal. I refused. I went to trial, got railroaded. They took my case to an all-white county near Lucasville, railroaded me, put me on death row.

Fast forward 20 years, I’ve been in solitary confinement since 1993. For the past 18 years, I’ve been at the Ohio State Penitentiary in Youngstown, Ohio – the supermax facility, similar to the supermax facility you guys got out there in California, Pelican Bay. And so I’ve been on lockdown 23 hours a day here for the past 23 years.

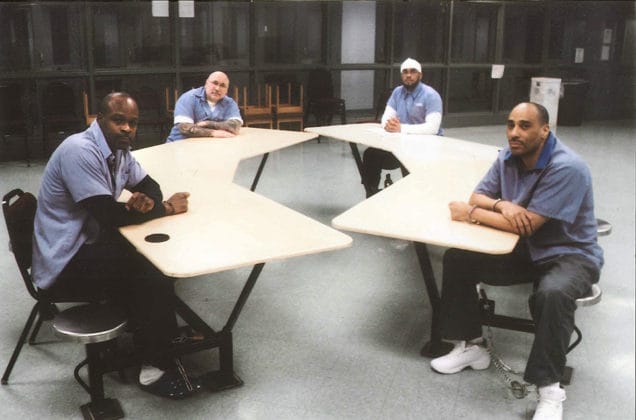

These men, made scapegoats for the Lucasville Rebellion 23 years ago are, from left, Bomani Shakur (Keith LaMar), Jason Robb, Siddique Hasan and Greg Curry, all incarcerated at Ohio State Penitentiary in Youngstown, Ohio. Not pictured is George Skatzes, who is incarcerated at the Chillicothe Correctional Institution. – Photo courtesy of Siddique Hasan and Greg Curry

Just recently my appeal was denied – moved me one step closer to execution. Just a few weeks ago, a new warden was appointed here and came in without speaking to us, without figuring out what was the lay of the land and just basically talking about stripping us of some of our privileges – particularly our CDs and books.

CDs and books, under these circumstances, are essential to maintaining your mental and emotional equilibrium. I wasn’t going to allow myself to be left in this cell – looking at the walls – without anything to help me cope with the daily mind numbing pressure you’re under in these types of circumstances.

So I decided to go on hunger strike so basically they didn’t push me to the edge, the brink of my existence. This final move was I think something – I wouldn’t say designed, because I don’t think the warden gave it any thought to how I would respond or react to his decision – I think these people make all these policies while sitting in their office without any sense how it will impact the people that they’re imposing these on.

But that’s how power operates: It don’t have any thoughts about how the policies and practices will affect real everyday people. That’s something – they don’t give a damn. I wasn’t going to allow all these people to push me off the planet, put me in the position where I’m constantly worried about my mental stability and what not. And so I went on the hunger strike.

The hunger strike ended a couple of days ago when the warden agreed that he had jumped the gun. He also agreed that we’d be allowed to keep our books and CDs and a few other things that will be worked out in the future – moving us to a less disruptive living situation. Because we’re long term prisoners, we’d have to file another lawsuit to order to have the state alleviate the pressure of the situation that we’re in.

But in the meantime we asked them to move us to another pod, a less disruptive pod, since we’ll be here for the duration, for the foreseeable future we’ll still be here. And so the hunger strike came to, I guess you could say, a peaceful resolution. We were able to keep our CDs and books and other additional extended property limits that we were afforded back in 2011.

Bomani enjoys a visit from family.

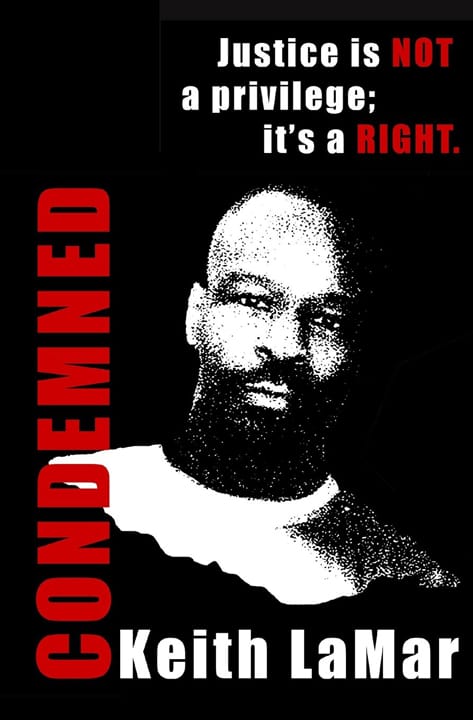

So that’s basically the gist of it. We’ve been struggling since 1993, trying to bring our case to the court of public opinion. I wrote a book as you know, “Condemned,” to tell my story from my perspective and try to give people a more in-depth understanding of what actually occurred and what’s still occurring right now in terms of the oppression, repression.

We’re trying to do interviews with the media; they blocked those so we filed a lawsuit to get the media in here so we can tell our side of the story. From the very beginning, that’s been the whole modus operandi of the state: Suppress the truth and present only what they want the public to believe. That again is how power operates.

Based on this one side of mainstream media – they tell their one side of the story – about what’s going on with Michael Brown, what’s going on with Missouri, what’s going on in the Middle East, all from the people in power positions. We’re just trying to – I’m personally trying to – fight against that, to stand up and represent myself the best that I can, given my limitations.

M.O.I. JR: Brother Bomani, where is your case at right now? And I know that the government is intending to try to assassinate you if us, if we the people do not get involved in a big way. Tell us a little bit about those plans.

Bomani: My case was just heard at the Sixth Circuit Court of Appeals – basically my last shot at release. They denied my appeal about a month ago, even though …

[Automated Voice: This call is originating from an Ohio Correctional Facility and may be recorded and monitored.]

Bomani: Even though over a hundred-some people attended my oral argument and witnessed with their own eyes the weakness of the state’s case against me – they fabricated evidence; they hid evidence; they couldn’t even defend their position – and still the three judges who presided over my hearing came back with a negative ruling, denied my appeal. And right now, I’m basically out of gas with respect to the legal situation.

We’re exploring options in terms of getting new counsel, because my attorneys – this case that I got caught up in, this situation that I got caught up in was very political – and even my own attorneys I think bowed to the pressure and didn’t fully represent my issues in the ways they should have been represented. So we’re trying to explore the options of getting an attorney outside of this state – hopefully without any influence by the political pressure of the state – to present my issues the way they should be presented.

Barring that, I might receive an execution date sometime in the near future. What we tried to do on the grassroots level …

[Automated Voice: You have one minute remaining.]

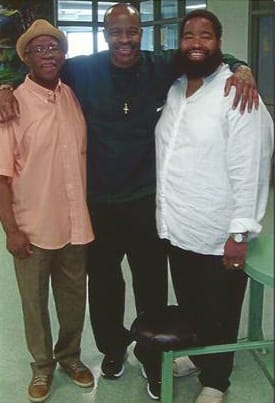

Bomani’s Uncle Dwight “Mannie” LaMar and cousin Tyrone Brooks pay him a visit.

Bomani: We started a Twitter campaign, there’s a documentary out called “Condemned”; you can go to my website, keithlamar.org, to view that. I’ve written a book, “Condemned” by Keith LaMar; you can go to my website again or to Amazon to obtain a copy of that. So we’re just trying to do it on our own, if nothing else.

Since if I’m executed, it will be done in the public’s name, we’re trying to get the public to be aware of what’s being done in their name. It’s a travesty of justice that’s being perpetrated in their name.

We’re just asking people, normal, everyday people, to get involved, to wake up and realize that the system is basically a sham – that it is unduly focused on poor marginalized people. In order for us to really address things in a way that need to be addressed, more people need to become aware, need to wake up.

So I’m just trying to do that, in addition to working with youth, trying to get them to see that the system is rigged, that it’s a trap …

[Automated Voice: Thank you for using Global Tel Link.]

Bomani: So we’re just trying to bring awareness to the public, trying to get them to participate in this process. There’s been a lot of protest going on across the country on college campuses and in the street. A brother just was recently murdered by police in Minneapolis, Minn.

Again, man, it’s just an ongoing thing where Black, particularly Black men and poor people in general are being oppressed and just slaughtered by the system and, you know, I’m a part of that, what’s going on with me, even though I’ve been afforded a trial. It’s basically more pretense than an actual trial or actual justice that’s being delivered in these cases.

We’re just trying to put it all together and so that it’s all connected, it all stems from the same thing: racism, oppression and the unequal distribution of wealth that all poor people are suffering from. It all comes from the same place. We all have the same struggle, the same enemy, if you want to call ‘em that, adversary or however you want to look at it; it’s all the same people.

M.O.I. JR: Can you talk about the prison movement in Ohio and what’s been going on in California. They’ve had the agreement to end hostilities to try to curb some of the Black on Brown as well as some of the other racial violence that has been going on, which is perpetrated by the state. Can you give us a view into what are some of the challenges the Ohio prison class is facing as well as …

[Automated Voice: This call is originating from an Ohio Correctional Facility and may be recorded and monitored.]

M.O.I. JR: Can you tell us a little bit about the challenges you guys face as a prison movement as well as what are some of the victories that the Ohio prisoner class has won?

Bomani: Well, the challenge that we face is education. A lot of these young guys in these gangs, it’s hard to explain to them that they’re brothers, that their loyalty should lie with each other no matter which random city they were born in or what not.

A lot of this stuff happens when these young guys don’t really know their history, don’t really understand who their natural enemies are, so they turn on each other, you know, because in here as on the street, poor people are fighting over limited resources. And so these gangs come about because of these limited resources and all of us trying to get access to them in order to eat, in order to live.

And so, you know, it’s an education process and that’s one of the reasons why I didn’t want my books to be confiscated, because a lot of these books – I’ve read them over and over again: George Jackson’s “Soledad Brother,” Assata Shakur. You know, all these different books that talk about the movement talk about the history of the struggle that we’ve been engaged in.

And so I share these books with these younger guys in hopes of trying to get them to open their eyes and realize the struggle that we’re all engaged in and to also start to understand that fighting each other is part of the problem, not part of the solution.

But it’s an ongoing thing because these places are set up so we can’t talk, so we can’t communicate. It’s against the rules to pass a book to someone else. It’s against the rules to stand in somebody’s cell and try to get them to see this larger picture. It’s against the rules because it’s against their interests to have these guys educated and what not.

Out in California, what they were able to do, Todd Ashker and all those brothers, what they were able to do with the end of hostilities – that was a monumental thing during the hunger strike that occurred out there. That was monumental.

And I think Todd admitted to being inspired by the hunger strike that we had back in 2011. It was three of us – me, Siddique Abdullah Hasan and Jason Robb – guys who were indicted and convicted after the riot. We went on a 12-day hunger strike and won that; I guess you could call that a victory. Although after the hunger strike was over, we still remained in the supermax.

Another family visit

But after 20 years we were able to touch our families, have full contact visits. We was able to access the legal database and what not. And so that was a small victory in relation to this bigger thing that needs to happen in order to change the system as a whole.

Here recently, as you know, the attorney general there in California …

[Automated Voice: This call is originating from an Ohio Correctional Facility and may be recorded and monitored.]

Bomani: … agreed to let over 2,000 men out of Pelican Bay out of solitary confinement. Those guys have been moved to other institutions and to other locations inside Pelican Bay, decreasing the level of sensory deprivation and what not, these very detrimental things that are inflicted on a person in these types of situations.

And so that was monumental, man, the pressure that you and reporters like yourself put on politicians by bringing awareness to the public and the rallies and what not that you guys had. And I think that has to be the pattern across the state, but it comes through this thing that you and I are doing right now.

Just having these conversations, broadcasting them to a wider audience, trying to get people to understand that we’re trying – that we need help to educate these young people. You know, just like I’m calling in talking to you, I also call in to juvenile facilities, I call in to high schools talking to kids who have been basically kicked to the curb because of behavioral problems, placed in classrooms like prisons, and so I’m talking to them about the very things I’m talking to you about – about education, about trying to gain some awareness about what’s going on, how these changes in society impact you personally and collectively.

So, it’s just a process of trying to educate people. When you know better, you can do better, obviously.

M.O.I. JR: For people across the nation and here on the West Coast, if they want to assist you and/or communicate with you, how could they do that?

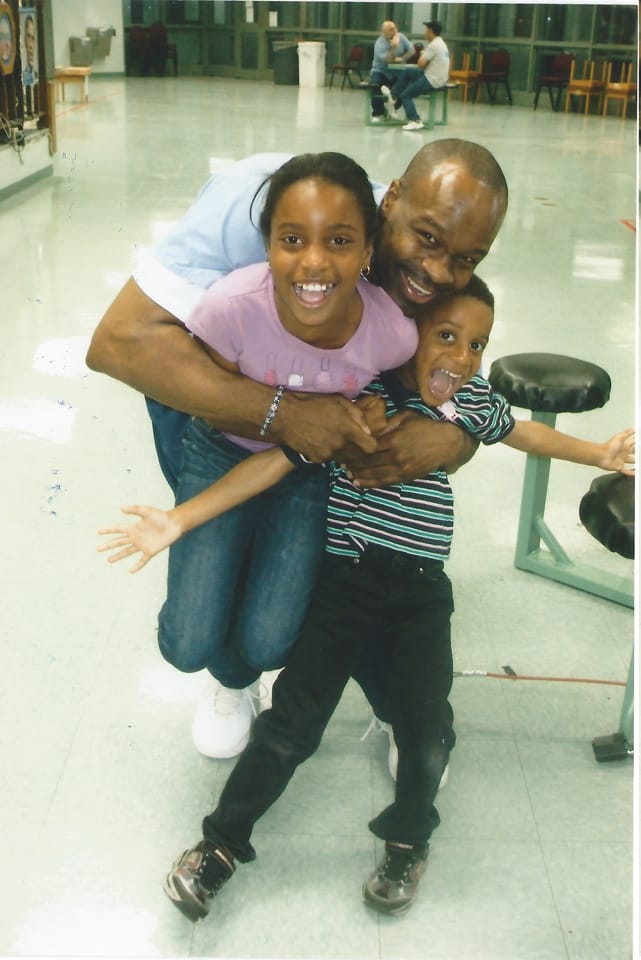

Joy lights up the dreariness of prison life when Bomani’s niece and nephew, Kayla and Kevin, come to visit. Youth are at the top of his agenda.

Bomani: Well, like I said, I have a website, keithlamar.org. Also, on Facebook, “Justice for Keith LaMar.” We’re starting a Twitter campaign, trying to raise awareness through that avenue, trying to use this technology to our benefit, trying to become a part of that mainstream process.

But yeah, go to my website, keithlamar.org, and from there you will find how to contact me directly here at Ohio State Penitentiary. And what we are trying to do – that is, me and my small network of people, friends and family are trying to do – is to bring my case to a larger audience.

But again, as I say, JR, my situation might not be able to prevent these people from killing me, murdering me. Mike Brown wasn’t able to stop them for murdering him. Eric Garner wasn’t.

So it’s not always that we will be able to stop these people from murdering us. They’ve been killing niggers in this country for centuries and I don’t think they have any intentions on stopping that any time soon unless we demand that it be stopped.

And I think that part of what we have to do as individuals and collectively is keep standing up to these people even if we must die in the process. Even if we must give our lives in the process, we have to still stand up because it’s the right thing to do and because youngsters who look at us, who are coming behind us can know that it’s not really about whether or not you get killed; it’s about whether you had the courage to stand up and live.

And so, that’s basically what I’m trying to do with my life. I’m trying to use my life as an example for these younger cats who are looking at me, who are coming behind me just to understand that you have to stand up. You have to say “No” when you’re being led down a road that you don’t want to go down.

You have to stop. You have to resist. And you can do that, even if it means losing your life, because at the end of the day they only can kill you one time, but you can die over and over again if you keep bowing down to this pressure. You feel what I’m saying?

M.O.I. JR: Yes, sir.

[Automated Voice: This call is originating from an Ohio Correctional Facility and may be recorded and monitored.]

M.O.I. JR: Well brother, we salute you. I push the Block Report listeners, the Freedom Now listeners, the Bay View newspaper readers and everybody else who can hear my voice to support you, to get involved, to get educated so that we know where to aim and how to fight. You know, bro, whatever you need we’re right here at your service. So let us know.

Bomani: Yeah, I appreciate that.

M.O.I. JR: Yes, sir. So let us know. And we will be talking to you very soon.

Bomani: OK, good, good. Thanks a lot, JR, man, you have a good day and stay vigilant, bro. Keep your eyes open, man. Keep doing what you’re doing ‘cause it’s very important, man. Thanks a lot. Much love to you, JR.

M.O.I. JR: Thank you, brother, and much love to you.

You were just listening to the voice of Bomani, formerly known as Keith LaMar, a Ohio death row political prisoner and survivor of the Lucasville Rebellion 23 years ago. He talked about the history of that rebellion, the recent hunger strike that he came off of, and the state of Ohio trying to set his execution date. If you’d like to hear more, you can go to blockreportradio.com.

Comments