Selected articles from this issue of the journal.

In This Issue

With our twelfth issue, Insurgent Notes returns to the fray. We do so in the further development of the atmosphere which has developed in fits and starts from the 2008 meltdown to Occupy to Black Lives Matter to today when, as our editorial analyzes, the center-right and center-left blocs of the two dominant American parties are seriously fraying at the edges, with promise of more to come, above all (hopefully) when the elections are out of the way.

Matthew Quest has given us a further installment of his work on C.L.R. James, dealing with James’s relationship with Cuba, an historical article which was suddenly made topical by the recent US-Cuban rapprochement.

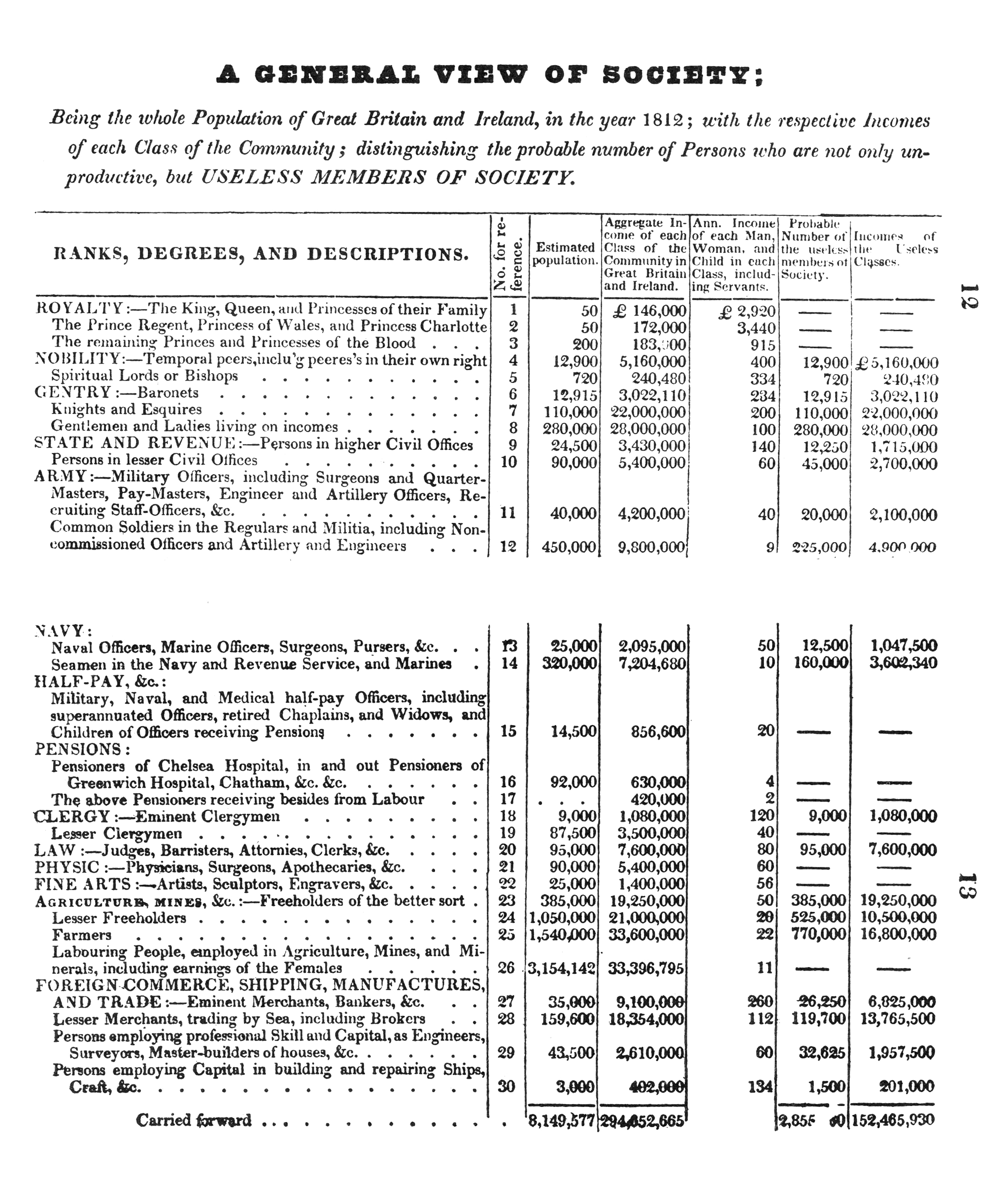

Jason Rhodes gives us a profound update and elaboration of his contribution to IN No. 1, (“Capitalism is a Waste of Time”), showing how, for 150 years, political economy from Malthus to Keynes (as distinct from Marx’s critique of political economy), bourgeois theoreticians were consciously attempting to divert attention from the huge costs of the consumption of the unproductive classes (those who consume and do not produce, Rosa Luxemburg’s lapidary “King–Ministers–Civil Servants–Professors–Whores”) and the potential—a shorter work week and greater wealth for all—if such resources and labor power were put to useful activity.

Loren Goldner turns our view to the global proletariat in articles on the struggles of immigrant logistics workers in Italy and on the class struggle in China.

Finally, in our book review section, John Garvey reviews the very interesting graphic biography of Rosa Luxemburg, Red Rosa by Kate Evans, featuring an artful use of graphics and of little-known quotes from Luxemburg’s life and letters, an excellent introduction to this woman who is one of the great inspirations of Insurgent Notes. Noel Ignatiev replies to John on the national question, as debated between Luxemburg and Lenin. And then John responds to Noel. More to come, for sure!

Finally, Loren Goldner reviews Beth Macy’s Factory Man, a book portraying the fate of wood furniture workers in Virginia and North Carolina, where the industry was largely wiped out by imports from China, Vietnam and Indonesia, another book made topical by the emergence of the “angry white male” as the apparent key to the 2016 election.

We anticipate that there will be much more to say and much more to do in the days to come.

Editorial from Insurgent Notes #12, April 2016.

Insurgent Notes doesn’t have much use for electoral politics as such. In our mind, they are useful mainly to take the temperature of society, especially to keep track with trends that emerge from the actions of the majority party of nonvoters. But American party politics have been dominated for so long by the “same old, same old” that with months to go until November, 2016 already stands out as an exception. Missing (so far) are the assassinations and nationwide urban riots that marked that last exceptional year, 1968. Most clearly in the case of the Republicans, but palpable as well with the Democrats, the “center-right” and “center-left” elites, who have graciously taken turns administering year-in, year-out misery for more than forty years, have lost control. It appears that Washington and Wall Street are loathed by a majority of people across the spectrum.

What interests us is not so much who will win—barring some as yet unforeseen upheaval, by no means excluded, it will be Clinton—as what will become of the huge bases of Trump and Sanders, once their leaders are defeated. The hard right within the Republican Party (typified by the Tea Party) and the far-right forces that operate within the party primarily for the purpose of seeking new recruits, having been newly legitimized by Trump, will not be going away. Our best guess is that the grass-roots activists in both camps will simply renew their pursuits of recruits. It may appear that there is little to do about it in either version. However, a friend of Insurgent Notes based in the Midwest, who has been closely watching the right wings at gun shows and elsewhere for years, tells us that some of Trump’s base could be attracted by a vision of a radically new society—if one were to exist in tangible forms.

Of course, what we’re mostly interested in is what might happen with the Sanders supporters. The moderate left, typified by the Democratic Socialists of America, has apparently enjoyed a bit of a renaissance. A review of the organization’s web page reveals the existence of a handful of high school chapters—we’re a bit jealous. Nonetheless, what they offer cannot possibly sustain the development of an anti-capitalist movement. We anticipate that many of Sanders’s supporters, having been drawn into a new world of anti-capitalist sentiments, will be looking for deeper understandings of the workings of the capitalist system and the ways in which more fundamental challenges might be organized against it.

Commentary across the board seems to see “angry white men” as the most contested terrain. We are aware of the recently publicized research findings about the rising death rates among white men between the ages of 24 and 59, while death rates among other groups, although still higher than those for white men, have been declining and the presumed relationship between their declining fortunes and their more or less self-inflicted misery. We suggest that it would be wise not to be distracted. Let’s instead ask a different question. For all the decades (more than four of them, and counting) during which American workers, white, black and brown, have been downsized, outsourced and deindustrialized, who has been talking to them? Not the elites of either party. Not the denizens of the cool “campuses” of high-tech firms in Silicon Valley. Surely not the middle-class left, which has been busy twisting itself into knots about various forms of identity politics.

Who, precisely, has been speaking to the hundreds of thousands of ex-workers and their extended families in ravaged ex-industrial cities such as Detroit or Youngstown or Pittsburgh or Buffalo or Rochester? Or to similar hundreds of thousands of working-class retirees and their families seeing their often-miserable pensions cut or eliminated? Or to the former furniture workers (there used to be a million of them) and their families in the forgotten small cities of North Carolina or Virginia? And who is speaking to such people today? Donald Trump and Bernie Sanders.

Let’s emphasize that we are more than aware of the pain and suffering (in injuries, chronic illnesses and early death) experienced by workers in industries like steel, auto, rubber, mining, textiles and furniture manufacturing, and we have no interest in seeing the pain and suffering of reindustrialization imposed as the price of progress. Nonetheless, we are acutely aware of the ways in which concentrated industrial production made possible remarkable forms of camaraderie on the shop floor and, beyond the workplaces, the establishment of towns and small and large cities where working-class families were able to create communities that came quite close to the kinds of communities we might imagine desirable in a postcapitalist society—communities where forms of mutual support were all but universally present and opportunities for children to pursue expanded horizons were real rather than advertising slogans. We need a restoration of the advantages of industrial civilization of the last half of the twentieth century without the reimposition of the pain and suffering associated with it. For the moment, we’ll hold off on the matter of the deep satisfaction involved with cooperative labor in industrial production—other than to say that we imagine a return of that satisfaction at a higher level. We should note in passing, to dispense with any America-centric lenses, Trump’s counterparts—a newly vocal hard and extreme right, anti-immigrant, anti-Muslim, anti-elite, and anti-globalist politics—that exist as well in a large swath of northern and eastern Europe, drawing support in part from the same downwardly mobile and ex–working class strata produced by the post-1970s crisis. This is the “bill” come due for all the intervening decades of invisibility enforced by the globalist “Davos”1 bourgeoisie, its captive media and professoriate, and, most importantly, by a left that accommodated itself to every twist of what we refer to as devalorization.2 A good segment of the world is moving to the right, in western and eastern Europe and in Latin America (with Argentina and ugly mass demonstrations in Brazil in the lead); for that, we can in part thank the moderate left managers of capital—the Clintons, the Obamas, the Blairs in the UK, the Hollandes in France and the Lulas and Rousseffs in Brazil. But that is not all that is happening.

A mere ten years ago, at the height of the “subprime” bubble and phony “wealth effect” of debt-fueled expansion, to imagine a self-declared “socialist” calling for “political revolution” attracting millions of people, and especially young people, would have been a bad joke. That 50 percent or more of Americans today define themselves as “socialists” or claim an interest in “socialism,” or that “socialist” is the most searched word in Merriam-Webster’s online dictionary: all of this is rather mind-bending for anyone who lived through the long, glacial winter from the 1970s until a few years ago. Occupy, Black Lives Matter and the Sanders campaign were and are all different responses to the same deteriorating situation.

It has taken a while, but the real toll of decades of economic decline culminating (so far) in the 2008 crash is finally emerging to the visible surface of social and political debate. We imagine that the Obama years will be remembered as a parenthesis in which a calm, well-spoken Harvard Law School graduate and first black president, with his predictable economic advisors (Tim Geithner, Robert Rubin, Larry Summers) restored, for a while, the appearances of normalcy, at least for Wall Street. Meanwhile, seven million families lost their homes and were ground down in every aspect of their lives; record numbers of undocumented immigrants were deported; one-third of young people, into their 30s, have been forced to move back in with their parents; the electronic police state, revealed (for any remaining skeptics) by Edward Snowden, was further consolidated; the militarization of daily life continued apace; 4,700 killer drone attacks were authorized by the White House, and the United States (with military installations in 110 countries and with a budget equal to those of the seven next largest armed forces combined) continues to play with fire with potential major wars in the Middle East, Ukraine and the South China Sea.

The Obama years may well be remembered as a parallel to the 1929–37 period, during which a lame state-sponsored recovery from the crash ran out of steam and gave way to preparations for war, and then to war itself. We know very well that Bernie Sanders still mainly operates inside the “white bubble” of American politics. While it seems remarkable to hear any major candidate call for free higher education and free healthcare and to consistently denounce the role of big money in politics, there is also a “clean Gene” element to Sanders’s appeal that avoids any head-on confrontation with the American blind spot of race. Who is this Brooklyn-born man who, after working with CORE (the Congress on Racial Equality) in Chicago in the mid-1960s, joined (consciously or not) the post-1960s white flight to the counter-culture paradise of Vermont to make his political career? He enlists himself in the long tradition of socialists, including his otherwise honorable role model, Eugene Debs, who said that socialism had nothing special to offer to black people. While nominally an independent for most of his decades in Congress, he has voted 95 percent of the time with the Democrats, including for Bill Clinton’s Omnibus Crime Bill of 1994.

Hillary Clinton, for her part, dominates in the black middle class, based on both their calculation that she alone can stop Trump and on rose-tinted memories of the Bill Clinton years, memories which somehow do not include the latter’s law-and-order rhetoric, the above-mentioned Omnibus Crime Bill leading to the incarceration of further hundreds of thousands of black and brown youth, or the abolition of welfare, forcing still further hundreds of thousands of single mothers to take minimum-wage jobs.

Polls show Sanders defeating Trump more decisively than Clinton could. Hillary Clinton will never shake her obvious association with the highest levels of Wall Street and Washington, not to mention her association with the sleaze that has dogged her and Bill Clinton and, more recently, the Clinton Foundation. Even her immediate natural base of middle-class feminists seems to prefer Sanders.

We ourselves cannot suppress a smile watching him make it hot for Hillary Clinton, who a year ago seemed on her way to a coronation and who responds to his lacerating comments about her Wall Street ties with a lame “let’s stick to the issues,” as if those moneyed ties of the political class across the board are not one of the issues. Trump himself has every chance of making mincemeat of her, if not for the chattering classes, more importantly for a significant part of the downsized white population, which already loathes her anyway. On the contrary, Sanders has been politically consistent since he was mayor of Burlington, Vermont, and subsequently elected to Congress from Vermont. There is no sleaze or waffling in his background. We acknowledge that the libertarian or far-left, in which we situate ourselves, have little or no contact with, not to say influence on, the working people, of any color, who are supporting Sanders, Clinton or Trump. Nevertheless, we have some ideas to offer. We begin our critique of Sanders with the old adage: the Democratic Party is a political roach motel: reformers check in, they don’t check out. Let’s explore why the adage applies. Sanders does not have much to say about extricating the United States from the disaster inflicted on Iraq and the ensuing whirlwind in the Middle East. He would be, willy-nilly, the commander-in-chief of US imperialism, and all that entails. When considering left-wing Democrats, it is sobering to recall that Woodrow Wilson (World War I), Franklin Roosevelt (World War II), Harry Truman (the Korean War) and Lyndon Johnson (Vietnam) were all (with the exception of Truman) on the left wing of the party. Republicans have historically been the party of wealth, Democrats the party of war. It is remarkable how apologists for this lineage focus entirely on the (already problematic) domestic agenda, and rarely venture into foreign policy, which, in a superpower where foreign policy is central, is hardly an afterthought. Barring a social and political earthquake even larger than the erosion of the two parties’ elites, a hypothetical President Sanders will be even more isolated and handcuffed before a hostile Congress than Barack Obama has been.

Sanders, his supporters will say, is different. Let’s stretch the envelope a bit and concede for the sake of argument: yes, Sanders is the most left-wing major candidate for president of the United States since Eugene Debs. But immediately we see that historical context, if not everything, is almost everything. Debs was the product of decades of sharp class struggle in the United States going back to the 1870s, and lasting to the 1930s. He himself had led some of those struggles and in 1912 got 5 percent of the vote as a socialist, at the peak of influence of the old Socialist Party, whose considerable left wing (Debs included) opposed American entry into World War I. He had emerged in an era marked by mass strikes and by the upsurge of the IWW. Imprisoned during World War I for sedition, he ran again from jail in 1920 and still got 1 million votes. Rosa Luxemburg he was not, but radical, especially in American terms, he was. Sanders only recently joined the Democratic Party in anticipation of running. We can hardly criticize him for not having the class struggle profile of a Debs, since the long empty decades prior to 2011 were no kinder to him than they were to us.

Enough, though, of elections! Let’s get back to where we began. What will become of Sanders’s considerable base when, as we anticipate, his not-quite-so-quixotic campaign ends? The current period reminds us, in a bizarre way and in much more dire circumstances, of the early 1960s. Then as now, an idealistic new generation was awakening to politics. Then as now, in both the nascent New Left and early civil rights movement (both deeply interconnected in the Jim Crow South) and today after Occupy and Black Lives Matter, something got out of the bottle that will not easily be put back in. We insist above all, where the potential role of our marginal milieu as conscious communists is concerned, that small groups do not shape consciousness, events do. Events for the 1960s were the later years of the Southern civil rights movement, the war in Vietnam, the radicalization of black people after the civil rights movement hit a wall, and the rank-and-file and wildcat upsurge in the United States working class. By the late 1960s, some many thousands of young people coming out of the New Left and the Black Liberation Movement had declared for revolution, and many joined groups organizing for it. It did not end well, for reasons that we cannot do justice to here. For the most part, the emerging revolutionary movement was dominated by either Stalinist/Maoist/Trotskyist sects or by groups well on the way to embracing an all-purpose, and hardly anti-capitalist, “progressive” politics. A not insignificant part of the black left turned towards nationalism. And a small part of what might be considered the middle-class white left was drawn into the substitution of terrorist violence for politics. Little of consequence is left of all of it although, to be fair, Sanders’s current vision has more than a little in common with the above-cited progressive politics.

For this new generation as well, events there will be, events that will demonstrate the dead end of electoral politics and, in short, of anything except mass struggle, a struggle which has already begun. There is no end in sight to economic crisis and decline: workers’ wages and pensions and the threadbare social safety net will continue to be cut; the threat of war on several fronts will remain serious; terrorist attacks will continue and probably increase (and will be used to intimidate the emerging mass movement); and black and brown people, immigrants and Muslims will be again be targeted. Our task, in those circumstances, is to intersect the fallout from Bernie, and contribute to the convergence of a consciously anti-capitalist movement that will say at last: “Hic Rhodus, hic salta! Here is the rose; here we dance.”

To be successful, a new movement will have to be armed with a theory of capitalism’s evolution up to the present moment, and a program that communicates a concrete vision of a world beyond capital, not one that merely seeks to paint the world green. This program is not “pie in the sky” but the conscious expression of what existing social forces on a world scale can already do, forces whose potential is the actual force undermining capitalist social relations everywhere. We are the opposite of utopians: we draw our force from a worldwide practice of working people and potential working people whose unwilling collusion with the dominant social relationships is what actually drives the world. “Material conditions” today begin with the huge productive power that is squandered and destroyed by these relationships; we might mention for starters the 2 billion people around the world consigned to the planetary social parking lots named Palestine or Pakistan or Congo or the Brazilian favelas, or to the suburban rings around Paris or Brussels, or the 270 million migrant workers in China, a permanent floating population in search of casualized work.

We continue with the hundreds of millions of wage-labor proletarians in North America, Europe and East Asia that modern ideology and mainstream media and academia have “disappeared.” On the other hand, we’d point to the emerging struggles in logistics (shipping, trucking, railroads, warehouse work, delivery services) where some of the most interesting struggles of recent years (such as the immigrants in the IKEA warehouses in Italy3 or the Hong Kong dockers’ strike) have made visible a vulnerability of capital in the heartland in some ways as acute as that provided by the old assembly line. In previous issues of Insurgent Notes, (above all issue No. 1), we have begun to sketch out the kind of program we mean. It includes an equalization of conditions upward around the world, taking the wealth currently wasted in the enormous “FIRE” (finance–insurance–real estate) and military sectors and putting it and the labor trapped in them to useful activity. We propose the large-scale reduction of the individual automobile culture whose ramifications probably make up half the “economy” in the United States, from fossil fuel consumption to the dispersion of population in suburbia and exurbia, all of this implying a complete reconfiguration of people’s living environments to overcome what Marx long ago called the alienation of city from countryside. When we consider the abolition of the military, police, prisons, state and corporate bureaucracy, along with the cashiers and customer service representatives of daily life—all sectors which consume social wealth and destroy it while producing nothing useful—untold horizons of possibility unfold from all the aspects of current social life which exist merely toenforce capitalist social relations. (See, for example, the Jason Rhodes article in the current issue.) We will have to deal with the emerging crisis of global warming, which itself alone implies a fundamental break with the way humanity produces and reproduces itself. Without this programmatic perspective, only minimally sketched here, the coming explosions will be doomed to dissipate themselves. Most people instinctively understand how absurd and meaningless much contemporary “work” is. Our task, or one of them, is to show, from the future struggles that will emerge, the “beach under the pavement” (to borrow a wall slogan from the French May 1968): how what is already possible can be made both conscious and practical.

A new movement will demand new forms of communications, language, education, political debate, cultural production and organization. We hope to contribute to the development all of those spheres.

- 1Davos is a resort town in Switzerland and is the site of the annual meetings of the World Economic Forum—effectively a gathering of the representatives of the world’s ruling classes and their favored advisors.

- 2In 1981, Loren Goldner, one of IN’s editors, addressed this issue directly. See The Remaking of the American Working Class: The Restructuring of Global Capital and the Recomposition of Class Terrain.

- 3See “Struggles in Logistics In Italy (2015).”

Comments

Matthew Quest in Insurgent Notes #12, April 2016.

Introduction

Many are the imperial crimes that can be detailed against oppressed nations’ sovereignty, and Cuba specifically. Given the recent visit of President Obama to Cuba, and the expression of his desire to end the United States embargo, these have again become common currency. And yet discussion of these impositions often paper over unresolved historical problems in the development of the anti-imperialist movement.

C.L.R. James’s “critical support” of Fidel Castro’s Cuba is little understood among scholars of his life and work. This essay explores James’s 1967–1968 visit to Cuba and reconstructs private debates and discussion on Cuba within his revolutionary organizations, based in Detroit, in the 1950s and 1960s, and among anti-imperialist movements. Many of James’s commentaries and disputes were consistent with his attempts to reconcile anti-colonialism with direct democracy and workers self-management.[1] If what it means to oppose empire appears fairly straightforward on the surface, the meaning of critical support of oppressed nations and the content of socialism, as a measure of evaluating radical developments in oppressed nations, is often obscure.

Empire is the military domination, economic exploitation, and cultural subordination of one nation by a foreign power. The search for identity of colonized people and the pursuit of self-government denied is not necessarily synonymous with rejection of the empire of capital or affirmation of labor’s self-emancipation. Support for national liberation struggles need not mean support for its aspiring leaders, in contrast to solidarity with an oppressed nation’s commoners. This only makes sense if we understand that there are conflicting tendencies within all freedom movements and to discuss them does not undermine but can enhance solidarity. James’s historical and political legacies, regarding Cuba, are dynamic measures for learning about these contours.

Critical Support and Workers’ Self-Management

How can we criticize a regime in a formerly colonized society, especially where it appears to embody a strong resistance to racism, empire, and genuine aspirations toward a socialist revolution? Still, what does Cuba solidarity mean when we find the Cuban Revolution has been at times neither socialist nor democratic, and has been repressive to Blacks’ and workers,’ gender and sexual autonomy? We cannot simply assume that James, anti-imperialist and revolutionary socialist, saw Cuba as the uncritical embodiment of the search for a new identity for the Caribbean—though this was at times his public stance.

“Critical support” of a former colonized nation that appears to be on a non-capitalist path requires a stance of “no blank checks.” This means the offer of solidarity is not simply evaluated by what imperialists think of the peripheral government it is seeking to subordinate. Nor can it be conceived only by what those governments claiming to resist empire might ask of anti-colonialists abroad. Rather, it is crucial what those offering solidarity also believe about the content of socialism and democracy. This may more easily be expressed at a distance than when visiting a foreign land as an official guest of the aspiring peripheral capitalist or socialist government resisting empire. Nevertheless, historically, this is something radicals have had to negotiate if we wish to offer solidarity to ordinary people, not primarily the governments above them. We should wish to learn about the actual social relations in that society, so we may return to educate our own people in what has been found abroad, not simply confirming everything we may have already believed in theory.

When we speak of direct democracy and workers’ self-management as measures of a future socialist society, there are some anti-capitalist thinkers of differing schools of thought who inquire if this emphasis obscures important tasks of the future or evolving socialist economy? For those who believe socialism is primarily a state plan above society not labor’s self-emancipation, that the market will be constrained by the state for the better, but not the wage-system or labor laws that discipline the working class in the name of national unity, their objection to direct self-government or popular self-management reveals “thin” conceptions of socialism and democracy. There may even be present autocratic tendencies in the name of national unity against the external imperialist enemy.

Still, there are others who speak of labor’s self-emancipation and workers’ self-management but who have more genuine concerns. For example, a self-managing socialist economy may find workers without bosses in water and sewage plants, steel mills, and farming bananas. But it might also find autoworkers in factories voting to abolish their jobs, deciding, for example, that luxury cars are no longer needed. With a commitment to social ecology and the expansion of public transportation, even modest cars may no longer be desired. Self-managing workers and farmers may wish to create cooperatives, as they directly plan a socialist economy. Cooperative relations can appear to overturn the thin idea of “jobs and justice.” Yet wage labor and capital relations may or may not be sustained. Self-managing farmers may reject the cash-crop culture of state-run marketing boards, even as the state claims to be concerned about the ravages of the market only to have an aspiring monopoly on foreign trade. How can statesmen from above society, or more decentralized cooperatives, claim to be eliminating market activities, if they accept in fact, that the market is essential to their own conception of political economy? Socialist transitions may be complex economically but this should not be an argument for less self-directed liberating activity.

Toilers may wish to abolish national boundaries, forging new federations, and eliminating job categories, like police. Some of these decisions authentically exist in tension, at least as conversations unfold, with decisions about national defense for a country such as Cuba, that has been subject to imperialist invasion and subversion. However, successful national defense need not mean a professional army with all the hierarchy and privileges this implies, centralization of spying and show trials, or neighborhood committees that only snitch but don’t actually govern.

Popular assemblies, workplace councils, or neighborhood committees, if they exist side by side with a nation-state for a time, should be able to maintain a record of policy disagreement (and independent initiative) with politicians above society, without finding themselves in prison or the subject of abuse. A self-directed decentralized government in embryo need not revel in proof of “reforms”—the taking off of restrictions the state had placed on their activities—for this type of surveillance should not be happening at all.

Working people who actually govern directly will be more confident in making decisions knowing that the necessities of life are not simply guaranteed to them as the subjects of welfare (or protected by the voice of a politician above society), but that these are the priorities of economic and social reproduction they make and fulfill themselves. But some can speak of labor’s self-emancipation and still have a very restricted sense of the content of socialism. This has something to do with a limited notion of democracy.

In view of the fact that American imperialists call their project of empire “spreading democracy,” many socialists mistakenly discard the idea altogether. Or some see it as defense of civil liberties under the state, which makes freedom of speech and assembly subordinate to the state, legitimizing the state as a permissive guardian of “rights.” Certainly, we cannot take seriously a “democratic socialism” that complains about “totalitarianism” where such advocates are “State Department socialists.” And yet, many supporters of Cuba have, in fact, been State Department socialists, for they have been concerned to mobilize the State Department for Cuba solidarity equally (if not more so) to mobilizing the American working people. Anti-imperialism should not be falsified as diplomatic history, or quibbling over comparative human rights and development standards—solidarity must be expressed by direct workers’ sanctions. To laugh at the latter as absurd is to accept that “socialism” and “democracy” are activities of professional administrators.

A direct democracy of popular assemblies, in addition to workplace councils, must mean pursuit of not simply self-managed economic planning, but also judicial affairs, foreign relations, education, and cultural matters. Direct democracy is not simply a process or an idea (“let the people decide”). Beyond a process or an idea about a form of government, it should also be a political program. There must be a striving for the abolition of professional intellectuals as the embodiment of culture and government. Those with specialized knowledge (military experience, technological know-how, ability in a foreign language, knowledge of history or political philosophy) can be delegated to facilitate a discussion or project but this should not make them a condescending savior. But even this proposition is not as precise as it could be. Should a vanguard be humble in the pursuit of the redemption of others otherwise seen as damaged or underdeveloped? The content of socialism, not simply its democratic substance but its equality, must be advanced in the future as well. Socialism is not affirmative action or equal opportunity to enter the rules of hierarchy, diversifying who gets to manage our lives from above (among the conqueror and the colonized). It should be the project of the abolition of hierarchy and domination.

We must pay closer attention to the elements and complexity of socialism in world politics, state power, political economy, and popular self-management as guided by C.L.R. James’s legacies, some of which are still obscure without primary and archival research. With these sources in play, James’s viewpoints on Castro’s Cuba, and that of his movement associates pursuing labor’s self-emancipation and colonial freedom, begin to have many more nuances than only surface readings of James’s books and essays in print may have led us to believe. James’s approach is not perfect or even consistent, though he cultivates illuminating moments and exhibits heroic acts at times in his own fashion. Rather, what James’s engagement with Cuba offers us, its strengths and limitations, is a series of questions we should be asking.

Direct Democracy and the Colonized Nation’s Search for Identity

C.L.R. James saw Fidel Castro’s Cuba primarily through the prism of a search for national identity and purpose for Caribbean people. But he also was part of conversations that insisted that socialist revolution, that Castro’s Cuba claimed to embody, must be distinguished by workers’ self-management. James is vaguely remembered for a critical discourse on Cuba begun as a report back from the Havana Cultural Congress of 1967–1968. Even as we record James’s attempt to retain an anti-Stalinist outlook that was his hallmark, we must keep in mind his ambiguities on Black autonomy and workers’ control in Cuba. We must also inquire what contributed to the muted aspects of James’s “critical support” of Cuba? While James was a very original political thinker and contributed to a sense of national purpose for Caribbean people against racial and colonial degradation, he always understood that popular self-government and radical democracy (majority rule) had to be the taking of power away from the minority, regardless of their racial or national identity, who ruled above society. Power to “the people” meant nothing if it was not an empowerment of the common people, not the professionals and elites who oversaw the Caribbean.

Cuba and the Double Value of State Capitalism

In Caribbean politics one must engage, oppose, or embrace C.L.R. James’s ideas when choosing one’s loyalties. An assessment of the Cuban Revolution as part of the Caribbean search for national identity, but also socialism, must overcome preoccupation with ideas originating from Moscow or Washington and London. Grappling with James’s analysis of state capitalism, developed within and later independently of the American Trotskyist movement, is part of making such an evaluation.[2] Given the dual character of James’s analysis of state capitalism, however, it is difficult to assert what that meant for his approach to Cuba. In contrast to his opposition to Stalinist Russia, James had “a less strident” and at times subtle opposition to Castro’s Cuba.[3] In a Cold War environment, critiques of state capitalism, as opposed to simplistic binaries of free market democracies and totalitarian one party states, could have many meanings. Castro’s Cuba has been condemned as a one party state dictatorship but also commended as a radical democratic experiment—could it be both these things? Many post-colonial moderates in the Caribbean Fabian tradition (as embodied by Grantley Adams, Eric Williams and Norman Manley) saw “socialism” as a welfare state that could be accomplished without blood, wearisome struggles, and disturbing empire. Clearly, Cuba had disturbed empire and the United States had attempted to topple Castro’s government many times during the Cold War—including trying to kill Castro by a poisoned milkshake, bacteria laced scuba gear, and exploding cigars.

Most, who have visited Cuba after the Cold War in the last three decades from the United States and expressed solidarity, speak of its education and healthcare programs, and return to the United States to vote for the Democratic Party. Is it not a peculiar disposition toward “a socialist revolution” to visit it, as a vacation abroad, while supporting bodyguards of capital at home? Did this contradiction in solidarity only emerge after the Cold War came to an end or was it rooted in how many people understood socialism? And what of these education and healthcare programs in Cuba? Is this the content of a social revolution? Does public housing, social security, and food stamps/debit cards make the United States “socialist?”

By the historical moment of the Cuban Revolution in 1959, James had developed an original body of political theory. Books like The Invading Socialist Society and State Capitalism & World Revolution explained how state capitalism (whether the one party state or welfare state) was an obstruction to direct democracy and workers self-management on a global scale.[4] Yet, he also began in the late 1950s and 1960s to also see state capitalist regimes in the Third World as the project of a progressive statesman who was aspiring to break up the former plantation economy and colonial order toward an economics of national sovereignty within the capitalist world system. This outlook could be found in his speeches about Caribbean federation and his address to Kwame Nkrumah’s Convention People’s Party in Ghana.[5] “Self-determination,” in the latter conception, was the push for the relative independence of local politicians and aspiring capitalists in Third World societies (in dialogue with the former and perennial colonizer as an aspiring peer). Negotiations with the IMF, World Bank, the terms of trade, loans, and debt were really negotiations about who would be the sovereign administrators of degraded toilers’ lives. Once state power was accomplished, the Third World statesmen, regardless of their relatively moderate or radical ideas, did not wish to encourage insurgency against themselves. We cannot forget this commonality between socialist and nationalist paradigms.

Simplistic discussions that compare the merits of “race first” and “class first” frameworks never capture the full contours of James, the Pan African and independent socialist. The peculiarity of seeking a genuine autonomy by negotiation and compromise, and not social revolution, for the colonized under empire is rarely challenged in Caribbean studies. Often insurrectionary tendencies and corporatist welfare state visions are conflated under one discussion of Caribbean Marxism.[6] Any discussion of James’s Cuba cannot submit to the notion that there is a singular “Marxist” paradigm. While it is true that a historical outlook on James can see his politics either retreating from previously stated political ideals or being strategic in different contexts as he moved between the Caribbean Diaspora and his native land and region, this awareness can still obscure much. Certain interpretations of Marxism do support the search for national identity among the colonized. But these same interpretations, especially by those affiliated with Moscow during the Cold War, could peculiarly divide the world between “fascist” and “democratic” imperialists—something James ridiculed in his first sojourns in Britain and the United States in a most entertaining fashion.

Neglected in most scholarly analyses thus far is how bewildering it is to promote a discourse of how capitalism undermined the development of peripheral or formerly colonized sectors of the globe while having no interest in pushing for the abolition of wage labor and capital relations. Capital, Karl Marx asserted without secrecy, actually is not produced by “nations” but by “labor.” All businessmen and statesmen, no matter their propaganda seeking to deceive their own people, in fact know this, and understand profits are something extracted from subordinate toilers. This is not to reduce a Caribbean anti-imperialist outlook to a “class first” position or deny the racial side of capitalism. But African, Indian, Amerindian, or Chinese autonomy in the Caribbean will not be a product of the world turned upside down if the content of independence, self-government, and socialism is perennially mystified.

Where James desired to cultivate the popular will in his politics, we must be alert when he is doing this essentially to advise and defend politicians to retain state power versus educating and agitating for ordinary people to topple hierarchy and domination. James’s viewpoints on Cuba emerged not merely from visiting that island nation. His debates and discussions within solidarity movements and his small revolutionary organizations helped shape his perspectives and critically inform his public stances. The 1959 Cuban Revolution allowed him to confidently break away from more compromised commitments, such as editing The Nation for Eric Williams’s People’s National Movement in Trinidad. His Correspondence group in the United States heralded the Cuban Revolution as “a turning point.” But James Boggs’s and Grace Lee’s emphasis on national liberation struggles in the Third World as increasingly beyond public criticism, exemplified by how they saw Cuba and their loss of faith in the self-managing capacities of the working class in the United States under the burden of what they saw as imperial and consumer privilege, compelled C.L.R. James and Marty Glaberman to break with them. The latter formed the Facing Reality group in 1962.

Organizational Debates during the Bay of Pigs and Cuban Missile Crisis

The Cuban Missile Crisis of 1962 immediately provoked contentious debate among the membership of the new Facing Reality group. Cold War media portrayals of Cuba’s subordination to, and dependence on, the Soviet Union, left Frank Monico, an actor by profession who had been visiting Cuba, unconvinced. Monico preferred to believe that Cuba was in control of the Russian missile bases on their soil. In contrast, Seymour Faber, a labor activist from Windsor, Canada, felt that Cuba is too corrupted by Stalinist influences to be worthy of the group’s support.[7]

The FBI, at the same time, harassed group members such as Constance Webb, James’s second wife, at her workplace. In a letter of November 11 1962, she revealed security concerns for the group as a result of Frank Monico’s travels in Latin America and the group’s public support of Fidel Castro. Webb’s letter also communicated the fact that the James circle had previously played a crucial role in arranging Castro’s reception and stay at the Hotel Theresa in Harlem, where he had the now-famous meeting with Malcolm X.[8] The owner of that hotel, at the time of the encounter between Fidel and Malcolm, was Love B. Woods, who ended that building’s practice of racial segregation around 1940. Woods, while recorded elsewhere as an African-American, may have also been a Caribbean sojourner.[9]

From the very beginning, James was very invested in the fortunes of the Cuban Revolution. He advised the group what their approach must be: each member would be permitted different positions on Cuba. We have previously delineated the contours of what these may have been. But similar to his past “blind eye” toward some members “burning up” to have a dispute about Israel, he advised Glaberman to make sure the debate did not rip the group apart.[10] James confessed, at the time of the Cuban Missile Crisis, that he was unclear about the actual penetration of Stalinist Russia over Cuba. Nevertheless, “as Marxists” he asserted, “we have to be the last to abandon Cuba either practically or theoretically.”[11]

From 1961 to 1963, associates of C.L.R. James, including James Boggs, Grace Lee, Constance Webb, Kathleen Gough, and Selma James were in constant correspondence with Robert Williams, who was in exile in Cuba, and Conrad Lynn his attorney. Conrad Lynn was coordinating a defense campaign for Williams, a North Carolina NAACP leader who had organized a militia to repel the Ku Klux Klan. Williams, who had visited Cuba in 1960 with the first African American delegation to travel there, was granted asylum to avoid an FBI frame up at the end of 1961. Nonetheless, Williams ultimately came into conflict with the Cuban authorities and by 1963 he left Cuba for Mao Tse Tung’s China. His perception was, that, after the Bay of Pigs and the Cuban Missile Crisis, the Castro regime, if not Castro as a singular personality, was becoming conservative.[12]

The James circles of influence had been involved with Robert Williams and Monroe, North Carolina since the famous “kissing case” (October 1958), where two little African American boys were jailed and placed on trial under Jim Crow laws, accused of kissing a white girl on the cheek. Lynn, earlier a friend but not a member of the Johnson-Forest Tendency, when he was a participant in the Leon Trotsky movement, received vital assistance from all his former comrades despite their factional disputes.

Selma James re-routed some of the Williams-Lynn correspondence past the American feds through her residence with C.L.R. in London. Constance Webb, a white woman born in California but who was raised in the southern United States, in daring and understated fashion, helped Williams and Lynn by taking a trip to Monroe to gather intelligence for the defense case. She flirted with the Monroe police chief, who had direct ties to the KKK. And, while in London, Webb sent Lynn contacts for a potential speaking tour and fund raising.

James Boggs and Grace Lee helped produce a major Correspondence pamphlet called “Turning Point in American History,” which contained two of Lynn’s speeches. Kathleen Gough, among the most personally friendly with Lynn, discussed and mailed her pamphlet “The Decline of the State and the Coming of World Society” to Williams in Cuba. These are all major reasons why the Correspondence and Facing Reality groups in this period were under surveillance in relation to the Cuban Revolution.[13]

Kathleen Gough’s Cuba Speech at Brandeis University

David M. Price’s Threatening Anthropology locates Kathleen Gough as among radical scholars in her field in the twentieth century who was under government surveillance from the time she visited with C.L.R. James in Trinidad in 1960 to after her rupture with him in 1961–1962, staying with the Correspondence group and taking the side of the circle led by the Boggses. The FBI obtained a copy of a speech Gough gave at Brandeis University to a student protest in 1962 leading to her repression in her workplace. Price offers the transcription in full. This speech tells us something about the perspective developed among James, his comrades and rupturing former comrades. Gough explained she was “not a liberal” but more radical than that, an “internationalist.” She agreed with the sentiment “Viva Fidel, Kennedy to Hell” expressed by protesters during the period of the Bay of Pigs Invasion and the Cuban Missile Crisis. Herbert Marcuse, who taught at Brandeis, and was later Angela Davis’s graduate school advisor, complimented Gough for having more courage than him to say difficult things.

Gough argued she was against war and nuclear war in particular. But in the event that extensive war emerged between Castro’s government and the United States, she hoped the Cubans would win. Gough explained that she admired Castro for putting down the Batista government, implementing agrarian reform, taking up attempts at literacy, building schools and hospitals, while ending corruption and prostitution. She was proud that Castro “sent the rich away empty to Miami” and that he supported the African American freedom fighter, Robert F. Williams. Yet Gough in characteristic Jamesian fashion also argued that she was disturbed by the summary executions during the Cuban Revolution, and those that followed with no justification. While she acknowledged that the United States threatened the safety of the Cuban regime, Gough was not sure that mass killings were necessary to establish its security. She argued that the mass killings that accompanied the Cuban Revolution were unfortunate and had been seen in every historical revolution, but it still disturbed her. She also found Cuba’s growing affiliation with Moscow, especially given her organization’s memory and concern with Stalinism, troubling. But this alliance with the Soviet Union had become inevitable with the Bay of Pigs invasion. Gough made it clear that she “does not support any nation” equipping themselves with nuclear weapons even as she supported the national sovereignty of Cuba.[14] What is remarkable are the similarities and differences of approach with that which James would take in his Cuba Report of 1967–1968.

The C.L.R. James and James Boggs Dispute

Stephen M. Ward raises some interesting issues for the conflicting tendencies we have been surveying in C.L.R.’s politics on Cuba. He explains that in 1956–1957, James Boggs debated C.L.R. about the merits of the spontaneous revolt of workers councils in the Hungarian Revolution in contrast to the emerging Bandung nation-states and what he saw as their aspiring progressive rulers such as Ghana’s Nkrumah, China’s Mao Tse Tung, and Egypt’s Gamal Nasser—especially because the Suez crisis happened at the same historical moment as Hungary. This was two years before the Cuban Revolution but foreshadowed the diverging conceptual frameworks that would soon emerge around socialism and national liberation. While Boggs professed to be equally excited about rebellions in all parts of the world, he began to make a distinction between labor revolts in Europe and the United States among white workers, and colonial revolts. He believed the latter should be more central in the Correspondence group’s approach. Boggs believed the colonial revolts disturbed the Western world whereas Hungary was used by Cold War logic in imperial foreign policy to create a false democratic discourse. These same white supremacists and imperialists who cried false tears for Hungary showed deeper fear of colonial revolt. Boggs also saw the movement up to colonial dependence for Nkrumah’s Ghana being strangely neglected by C.L.R., which was also occurring at the same historical time as the Hungarian revolt of 1956 and its aftermath. James was seeking to sustain labor’s self-emancipation as part of his conception of the Ghana anti-colonial revolution, and while going further than James Boggs, ultimately failed.[15]

However, Ward could have clarified better, in his overwhelmingly insightful approach to Boggs, C.L.R.’s emphasis on Hungary at this historical moment. He favors Boggs’s view as mirroring an unfolding historical consensus while mystifying whether Boggs, in contrast to C.L.R., had the sharper political analysis for both the colonized, and modern industrial nations’ toilers.

This mystification is part of a simplification. C.L.R. in 1961–1962, and in the earlier conflict with Boggs, did underscore that “the real issue” was the American working class’s capacities for self-emancipation—for this was the location where they were collaborating to build an American revolutionary organization. For many at this juncture, inside and outside their organization, the real issue was racism and opposition to empire in an increasingly vulgar materialist analysis of modes of production, not the struggle of social classes. The latter of course had to be propagated not just observed, as did opposition to racism, sexism, and empire. When combined with his valuing of worker’s self-management in Hungary, C.L.R. could appear to be flat footed, when contrasted with Boggs, in the transition from the Age of the CIO to the Third World national liberation epoch. But Boggs, as many anti-colonial thinkers before and since despite their Marxist analysis, was not prepared to see labor revolt within post-colonial societies as crucial to socialist revolution. Ward’s Boggs fails to inquire why and instead saw the American working class as increasingly a signifier for the white racist working class (this had not been so in their earlier collective work of 1957–1958). C.L.R. and Boggs agreed the Age of the CIO was declining and coming to an end. But C.L.R. did not see the American working class—which was not only white and racist—declining because of racism’s relationship to undermining the class struggle. He certainly was militantly opposed to racism and colonialism and was not forgetting himself. Instead, C.L.R. was challenging Boggs and the Correspondence group that their special brand of Marxism was not a fusion of a flat historical materialism and a critique of racism and empire. A paramount thread was the direct self-government and autonomy of all oppressed sectors of American, Western and the colonized spheres. Further, one does not simply observe social movement realities at each historical moment but speculates about their meanings for the future.

In Facing Reality (1958), initially a book by the Correspondence group that emerged a year before the Cuban Revolution, Boggs and C.L.R.’s dispute was reconciled in an ambiguous tension. On the first page Facing Reality declared, “the whole world lives in the shadow of state power.” This was a thread that declared the content of socialism as direct democracy and workers self-management. In contrast, it argued in another chapter “the new society” and “new people” could be ushered in by nationalist politicians of the Third World where labor did not especially hold the reins of those movements.[16] This is obscured by Ward and many observers before him. Boggs could not understand why behind the scenes in private organizational correspondence, and despite being associated with Kwame Nkrumah, why C.L.R. was not excited about the emerging “independence” of Ghana in 1956–1957. Instead of dividing the world into “the white world” (which was how the Bandung conference was speaking) and the global victims of the colonizer, C.L.R. was seeking to reconcile together the search for national identity of the colonized and workers’ self-management one year before the Cuban Revolution emerged.[17]

Ward recognizes this tension between workers’ self-management and national liberation in the second major dispute between James Boggs and C.L.R. James in 1961–1962. But Ward’s Boggs sees the Correspondence group’s analysis of bureaucratic state planners as not equally applicable to the American working class and the colonized toilers abroad. This is why a careful approach to the contours of C.L.R. James’s shifting approaches to state capitalism is crucial. Boggs at this historical moment did not have a nuanced valuing of state capitalist analysis and instead abruptly discarded it for peripheral nations—at least where it was seen as repression of workers self-management.

How should the Correspondence newspaper have responded to the early Cuban revolution? Boggs wished to defend the Cuban revolution in an array of propaganda primarily centered on struggles for civil rights and anti-colonialism. C.L.R. James’s and Marty Glaberman’s approach in this dispute was that the Cuban Revolution had to be explained to “the American workers” (not the American “white racist” workers in any permanently damaged and psychotic sense) from the perspective of workers self-management. Ward is correct that while C.L.R., Glaberman, and Boggs agreed that that the Cuban revolution deserved “unqualified support,” nationalist autonomy meant for Boggs that Cuba, seeing their identity as equivalent to the Castro regime only, could “arrange their revolution as they wished.” C.L.R. and Glaberman, in contrast wished for a strategy for agitation and propaganda to the multi-racial American working class that searched for in Cuba radical “non-party” political forms and the efforts at labor’s self-emancipation through workers “self-organization” in Cuba.[18] As we shall discuss subsequently, these forms and efforts existed before and after the early Cuban Revolution of 1959.

Toussaint L’Ouverture, Fidel Castro’s Cuba, and Hungary

In 1963, the second edition of The Black Jacobins was printed with a new appendix that linked Toussaint and Castro as part of the Caribbean search for national identity. Perhaps more scholars of James’s life and work are familiar with this treatment of Cuba by him more than any other. The essay by C.L.R. elides class conflicts within the Haitian Revolution and raises no critical perspective on the Cuban Revolution. “The Gathering Forces” manuscript of 1967, written for the Facing Reality group but unpublished, presented the Third World as completing the Russian Revolution. On one level, it suggested that Russia had completed the struggle for socialist revolution. But James’s Lenin, based on the latter’s last writings on literacy education, peasant cooperatives, and the workers’ and peasants’ inspection, that insisted that there could never be a complete socialism in a preliterate culture distinguished by fragmented productivity, appeared. There is a tension between the Hungarian Revolution, which embodied direct democracy and revolution in modern industrial nations, and Cuba, an underdeveloped country which is also depicted as partially distinguished by direct democracy. While the Cuban Revolution is said to be a product of a series of general strikes, “The Gathering Forces” argued that it completed the Russian Revolution not so much by independent labor action, but rather, by seeking to humanely abolish value production in economic planning in contrast to harsher and insensitive Stalinist visions.[19] Some of the tensions in James’s comrades’ interpretation of Cuban political economy are a product of the tensions between direct democracy and national liberation in his own politics. Yet we must also be alert to shifts in James’s analysis and inquire what are the merits of looking at labor and colonial revolts as distinct movements on separate terms—for many historically view these separately from a vulgar historical materialist lens. The revolt against surplus value production (wage labor and capital relations) initially a self-emancipating rebellion of labor, could subtly be recast as an act of certain state capitalist planners in peripheral nations, where labor did not hold the reins of society. This would be consistent with Boggs’s earlier dispute with C.L.R. James.

The Hector-Roberts Debate and Ken Lawrence’s Critique

The influence of Alfie Roberts’s Caribbean International Service Bureau (CISB), based in Montreal, was at its height within the Facing Reality Group in 1967–1968, as is clear in the Cuba section of “The Gathering Forces.” The CISB also included Tim Hector, who later led the Antigua Caribbean Liberation Movement, and Franklyn Harvey, later a major leader of the Trinidad based New Beginning Movement and mentor of the Movement for Assemblies of the People, a forerunner of Maurice Bishop’s New Jewel Movement in his native Grenada. James’s study circles with these Caribbean youth illuminate his take on Cuba at this historical moment and aspects of what he taught the Caribbean New Left generation.

C.L.R. James had initial disagreements with Alfie Roberts on the proper interpretation of Cuba. The Cuban Revolution, as a part of the search for Caribbean autonomy, while certainly an influential framework for the Montreal circle, cannot easily be said to overshadow a sympathy for direct democracy among certain members. In 1967, among activists like Harvey and Hector, the affirmation of direct democracy was sometimes greater than James’s own emphasis at that juncture. This is especially so when compared to James’s comparatively lesser faith that such ideas could be applied to peripheral nations five years after the heated debate with Boggs and shortly after his only electoral campaign, with the Workers and Farmers Party, in Trinidad one year before.

David Austin, the major scholar of this Caribbean Black Power circle in Canada influenced by James, reminds us of a little known “Hector-Roberts debate” that lends light to contextualizing the conversations James was having about Cuba with Caribbean activists in Canada. Both argued within two evolving frameworks. Hector argued the Cuban Revolution was not distinguished by mass participation; it was a nationalist revolution not a socialist one. The Cuban state was vanguardist and did not meet the criteria for a socialist future as outlined by James in his original political theory. Roberts, in contrast, always more sympathetic to the Soviet Union, argued that Castro’s pronouncements on state power suggested that the society would soon go in a socialist direction, as led by Castro from above.[20]

In a February 18, 1967, letter, in response to internal debate about “The Gathering Forces” manuscript, Ken Lawrence shared with his comrades his dissatisfaction with the section on Cuba. Because Lawrence was reading the work in an earlier draft, we cannot be sure how the Cuba section appeared at that time. Nevertheless, Lawrence’s discussion revealed other questions in James’s circle.

Lawrence’s contentions about the diverse forces that overthrew Batista show that before James visited Cuba, he had access to critiques of Castro that could not lead easily to the conclusion that Castro was the most radical or democratic force in the Cuban Revolution. Batista, in Lawrence’s view, was overthrown primarily through sabotage and armed conflict in Havana not the rural campaign of Castro’s July 26th Movement (J26M). The urban movement led by workers in the Labor Unity (LU) group and the Revolutionary Directorate (RD) took the major brunt of the casualties in the conflict. J26M had ten times fewer casualties and probably lost comparatively few leading cadres. It was significant to Lawrence that LU and RD were disarmed and their leadership replaced by choices handpicked by Castro. The circle around the journal Vos Proletario was also smashed. Many left wing critics of Castro, not merely counter revolutionaries, were known to be “rotting in his prisons.”

Lawrence argued that while all of this may not be enough to indict the Cuban regime “in full,” the James group should not speak so vibrantly of the personalities of Fidel Castro and Che Guevara as making immortal contributions to civilization, “particularly, when they say things which we are so eager to believe.” Lawrence here is influenced by C.L.R. and Glaberman’s position in contrast to Boggs’s approach. Lawrence argued, “I will be a lot more interested in them when they tell us something we didn’t already know” about socialism, “or better still when they have proved us wrong about something.”[21]

Marty Glaberman: From “Critical Support” to “Genuine Exchange?”

Thus the discussion in James’s group exposed him to critical outlooks on Castro’s Cuba before he actually had a chance to visit. We must keep this in mind, even as James, in published remarks on Ernesto “Che” Guevara from a 1967 memorial meeting in London, perceived him as the embodiment of world revolution, the heroic guerilla, and the Cuban Revolution.[22] Rarely, save for the defense of the Mau Mau of Kenya, did James place guerilla warfare as central to his radical vistas. Marty Glaberman’s statement on the Cuban Revolution in May 1968 tells us something about the outlook James was bringing to his visit to Cuba and what he would have shared with his comrades upon his return:

A genuine exchange exists between those who are leading Cuban society and those who make up the basis for the society, and within that framework, it is not a matter of saying Cuba is a socialist society, or is not a socialist society. It is possible to say Cuba is developing in a direction, to the extent that it can, of building a socialist society, but the building of that society is only possible in the framework of the industrialized world.[23]

Glaberman’s perspective on Cuba is very informative for how James’s organization was thinking about socialism for peripheral nations after the split with James Boggs and Grace Lee. First, what is “a genuine exchange” between leaders and led in a socialist society? Second, what does it mean that those who do not lead are “the basis” of that society which aspires to approximate socialism? Third, a capitalist society must be rooted in the framework of an industrial economy but why also in a “socialist” society? Glaberman, like C.L.R., who wished to avoid assessing whether Cuba was a socialist society or not in public, did not seem to have a valid criteria for distinguishing between national liberation (resistance against empire) and a socialist future as equal to workers’ self-management.

This was remarkable because Marty Glaberman often tried to sustain the state capitalist analysis he shared with C.L.R. from the late 1940s through the late1950s that used one vision of a critique of political economy to measure labor’s self-emancipation for the whole world. In the initial argument with James Boggs in 1961, Glaberman agreed with C.L.R., that critical support of Cuba should be framed with an emphasis on the self-organization of Cuban labor. Yet by 1968, Glaberman was recasting Castro as cultivating the popular will with muted public criticism.

Anton Allahar and Nelson P. Valdes see in Glaberman’s and James’s perspective that social revolution is about “contradiction, change, advances, and reversals, and even periodic stagnation.” But is it the Cuban state or the Cuban people who are advancing, retreating, or stagnating? There is a critical tension in how Allahar and Valdes marshal Marx’s Capital and Lenin’s political economy while being alert to James’s critique of bureaucracy.

In certain respects Castro was aware that without the masses increasingly solving problems themselves the revolution would become bureaucratized. From another vantage point though, Castro’s state can critique problems of bureaucracy while obscuring that it was the Castro regime which was the force of hierarchy and domination. It is not merely that Cuba needs external allies to facilitate a different type of economy in a hostile world.[24] Direct democracy is something which can be organized even under scarcity in peripheral nations. If this is not plausible than equally a peripheral nation-state’s claim to critique bureaucracy should also be seen as inauthentic. For the critique of bureaucracy than becomes a challenge of one sector of state or party hierarchy against another.

James’s Cuba Report

James visited Cuba for more than four months from late 1967 until the early spring of 1968. His “Cuba Report,” a transcript of a public lecture given in London, suggested problems in evaluating the revolutionary content of societies after a short visit as a guest of the state. “You know, I have listened to a lot of people who went to Russia in 1936, and they came back and said all they had seen, the number of people…getting on well and doing well…backward, but in reality full of hope and prospects.” After the visitor’s return, however, within a few months, Stalin created show trials and shot many of the people the visitors had met.

Carrying the burden of anti-Stalinists in the 1930s and perhaps more subtly in his 1968 analysis of Cuba, C.L.R. James made a public challenge to those aligned with Moscow and perhaps their influence on and interpretation of Cuba. James reminded his colleagues that he questioned past assessments by those who visited Stalinist Russia and thought what they saw was a progressive society. James’s opponents dismissed his criticisms as that of a treacherous Trotskyite traitor. “So,” he explained, “they went back in 1937 and said ‘Well this time, the folks we have met, I mean these are the real people.’ They were scarcely back when Stalin shot more than he shot the time before.”

James introduced his “Cuba Report” with a cautionary tale perhaps hinting at his own concerns about: “How wrong you can be, on an estimate it is difficult to say.” He appeared to allude to evidence of show trials, political prisoners, and summary executions under the Castro regime but never clarified the nature of what he may have been aware or made this central to any public statements on Cuba.[25] A historical approach to James’s “critical support” of Fidel Castro’s Cuba must make a clear distinction between the production of agitation and propaganda for public exchanges and private internal organizational discussions where more complex nuances may be expressed in internal debate.[26] James insisted that the achievements of Russia could not be reported by discussing the supposed economic and welfare achievements of the Five Year Plans. Here is a reference to his state capitalist analysis not merely of Russia but of all nation-states on a world scale. Though he wished Nkrumah in Ghana well, he knew that discussion of all the factories and roads Nkrumah had built, and his Volta River project (the Akomsombo Dam) didn’t explain properly his society either. Just because an ex-Trotskyist (Michel “Pablo” Raptis) had advised Ben Bella on economic planning in Algeria, James asserted, his view on the problems of state planning there had not changed.

James’s perspective desired not to get lost as a witness to a society based on a few days or months. His “Cuba Report” purposely did not emphasize how many roads had been built or how many children had been sent to school. His vision of socialist revolution was not one that was concerned with increasing material welfare alone, but rather as a revolt against value production itself. Further, James contended, the great number of professional people trained in Cuba—a surprisingly large number of doctors, engineers, and economists—were in fact a liability, and not the much promoted advance. These newly formed elites would only create a bureaucracy who would imagine themselves, at best, as society’s guardians.[27]

After examining the historical legacies of Jose Marti, Maximo Gomez, and Antonio Maceo and the anti-colonial struggle of 1898, and Fidel Castro’s initial defeat at the Moncada Garrison in 1953 after which he gave his famous speech while on trial, “History Will Absolve Me,” James explained that Castro’s call for a greater democracy and justice for the peasantry captured the spirit of national purpose making inevitable his success in 1959.[28] But James explained, that unlike in the Russian Revolution where the appearance of soviets (workers’ councils) preceded Bolshevik seizure of state power, and unlike the great Putney Debates in Cromwell’s Puritan Revolution about the validity of a standing army, the Cuban Revolution, if not a mere coup, did not follow upon mass direct action initiating a challenge to bureaucratic conceptions. Without overstating the forces on the ground in Cuba fighting for a libertarian or romantic socialist revolution in 1959 distinguished by a self-managing autonomy, one could get the mistaken idea from James’s analysis in this transcript that such forces were not present at all.[29]

James asks in his “Cuba Report”: “Is it a one party state? Is Castro’s party the one party and other parties prohibited, prevented or sat upon in the same way as we have seen in Eastern Europe and which the world today is beginning to understand is the surest way to tyranny of the worst kind?” James suggests, rather, that Fidel Castro’s Cuba was faced with the challenge of initiating a democratic revolution after seizing state power with an army.[30] The necessary socialist content, he asserts, only became clear to Castro after the 1961 Bay of Pigs invasion by John F. Kennedy’s United States.

James, inspired by the writings of Lenin, who he insisted: “absolutely refused to be a dictator,” argued that coercion applied to the middle strata of the peasantry does “great harm.” Facilitators of socialism needed to avoid trying to control this class and must become masterful communicators in their cultural idioms winning them to their side. James argued that Castro’s revolution had not only put an end to sharecropping and granted the peasantry ownership of the land but had also allowed small family owned businesses not to be nationalized so long as they didn’t employ new wage earners.

Castro had ended the control of landlords, who lived by collecting rent, over many houses, but had generously, in James’s view, not seized the homes of old Creole nobility. Castro’s state capitalism, in James’s eyes, had the tendency of sensitive compromise—unlike Stalin’s approach. Shortly after the purging of Anibal Escalante, C.L.R. saw the Cuban Communist Party members he had met as, from “head to toe, superior people in morality and general behavior.”

On the Isle of the Pines, Cuba experimented with a program educating young leaders to become “the new men,” by seeking to stamp out consumerist and capitalist instincts, in exchange for financial arrangements taking care of their families’ needs. James suggested that the Cubans were hoping to develop skills, make these youth “heroes in production,” and internationalists like Ernesto “Che” Guevara, who had been killed in Bolivia shortly before James’s visit.[31]

James also saw in Cuba an effort at the reconciliation of mental and manual labor. Encouragement of quality and quantity in production, and participation in economic planning were happening, but still elusive was self-government at the point of production. However, as James also explained in his “Cuba Report,” just because the Cubans had the goal of socialism, one could not assume that they, themselves, were clear on how they would get there. But, they were attempting to innovate as an underdeveloped peripheral nation in the world economy, which, James attests, is very difficult.

At the Cultural Congress at Casa de Las Americas, James had found Cuba’s conception of the role of intellectuals in the Third World and the proletariat in advanced nations to be entirely wrong. Guests were taken to see Cuban popular art, music, dance, and theater, but James wondered why there were no ordinary Cuban workers and farmers participating in this cultural congress? They should, he says, have been part of the discussion and debate as to how to prepare this conference, not excluded and reported to in the newspapers after the fact. James goes even a step further: Why was there so much concern over shortages of food and oil in Cuba, yet the visitors were treated like royalty, driven around in cars, put up in a hotel with a cornucopia to eat?

Race and Cuba

James contested Stokley Carmichael (later Kwame Ture), who had told Cubans about how the American white working class was racist and privileged following the evolving analysis of Boggs. Instead, C.L.R. maintained the white workers of imperialist countries had revolutionary potential. To say they do not, he protests, is not Marxist, since, as Marx himself says in Capital (Volume One), the proletariat is united and disciplined, be their payment high or low, by the very contradictions of capitalist production itself. Whether this was an accurate approach to Karl Marx’s theory by C.L.R., the French workers shortly appeared to prove him right, despite being from an imperial nation, in their rebellion of 1968.[32]

C.L.R. has some interesting anecdotes to share about what has by now become a perennial debate: the extent to which the Cuban Revolution has eradicated racism. James, after a few weeks visiting, shares what he observed about where that struggle had developed after nine years of the Cuban Revolution. To great laughter, he claimed, “Number one, the African influence, the African religion, the African art, have an enormous influence on Cuba and are still powerful to the present day. You know that is not so in Barbados.”[33]

Second, James did not see many dark-skinned people around the hotels in Havana where they stayed, but he saw a disproportionate amount at a public demonstration celebrating independence. While there weren’t many Black people among the teaching fraternity and professional intellectual classes, they seemed to be fairly represented in every other profession. “But elsewhere they couldn’t move a yard without the support of Black people. If Black people were dissatisfied the thing would fall apart especially around Havana.”[34] James observed in the Cuban newspapers that Black people were doing well in track and field, in tennis, and in other sports. He inquired to Cubans of fairer skin what they thought the meaning was of these disproportionate achievements in sports, in contrast to their comparative absence in government jobs and limited pursuit of formal education? He was impressed that their responses “didn’t fool around.” Appearing to be sincere, those whom C.L.R. was in dialogue with made clear they felt there was no problem that could not be overcome.

James’s counterparts weren’t anxious when faced with the proposition that Blacks appeared to achieve so much in sports and not in some other sectors of Cuban society. James recalled their reply, but was perhaps partially embellishing his presentation with his own style. Blacks had lived “a hard life.” They disproportionately had come from the peasantry and ex-slave populations. If Blacks were given the same educational opportunities, they would be better represented in the upper echelons of Cuban society. James said, in contrast: “in America,” distinguished by white supremacist doctrine, “they fool around and pretend” the problem “doesn’t exist.” “But the people I spoke to in Cuba, some intellectual, were very firm about it and that is something rather unusual.”[35]