Complete contents from this issue of the journal.

Insurgent Notes No. 13 presents an array of articles reflecting the rising curve of revolt and political turmoil in the United States and abroad. We begin with our editorial “President Trump?” on the current, fast-evolving situation of the strangest political year in the United States since 1968. We follow with Michael Hough’s historically rich article on the evolution of labor racketeering trials in the United States, culminating in the little-noticed conviction and sentencing of a Philadelphia Ironworkers’ president in 2015. John Garvey’s “Notes on a Future Politics (Part One)” offers a detailed account of the forces, over several decades, which have converged in the Trump phenomenon. Jarrod Shanahan recounts the recent revolt in the commissary at the notorious Riker’s Island prison in New York City this past summer. Following on this, and presenting a larger historical perspective, culminating in the organizing for a nationwide prison strike, Amiri Barksdale traces a history of little-known prison revolts in recent years, as well as those by immigrant detainees.

For an international perspective, our Southeast Asian correspondent Art Meen’s “Strike Wave and Worker Victories in Cambodia” offers a concise overview of a militant working class in motion in struggles largely off the radar in the west.

For historical perspective, Mitch Abidor writes up his recent interviews with 40-odd veterans, from across the political spectrum, of the May―June general strike in France in 1968, followed by two critical comments. Last but not least, Jason Rhodes discusses Ashwin Desai’s remarkable book Reading for Revolution.

Insurgent Notes editorial from issue 13, October 2016.

President Trump?

It just might happen. What seemed, a year ago, like a laughingstock candidacy is now a plausible winner in the wildest political year (and there is still the forthcoming “October surprise”) since 1968. No matter what happens, the old US party system is broken. Donald Trump is like no major candidate in living memory. Just as one had to reach back to Eugene Debs to find a candidate as seemingly radical as Bernie Sanders, finding a serious precursor to Trump is even more difficult. The quiet eclipse of Sanders in August guaranteed that many of his ex-supporters will stay home or vote for the Green Party. Respectable official society, including a good swath of the Republican establishment and even the normally “apolitical” military, is either in withdrawal or openly supporting Clinton. Generals, diplomats, foreign policy wonks and the New York Times all agree that a Trump presidency will be a disaster. The Financial Times sheds tears over the possible demise of the “internationalist” (read: US-dominated) world order in place since 1945. Such declarations make no difference; if anything, they only add to Trump’s “anti-establishment” credentials and panache.

The situation shows important parallels to the Brexit vote in Britain in June; there, the entire political and academic establishment, “left” or “right,” came out to “remain” in the European Union, and something like a class vote (albeit mixed with other less savory elements) came back with a big middle finger. That is what is brewing in the United States. What is occurring is nothing less than a (very) skewed referendum on the past 45 years of American politics and society, and those who feel they got the short end of “free trade” and “globalization” think they have finally found a voice, even as Trump’s economic program, such as it is, is a chimera. Just as in France or in Britain, the new right-wing populism does not make its inroads in the wired yuppie metropolitan centers of Paris or London, but rather in the passed-over middle and small towns, including towns where gentrification has forced the former urban working class to relocate. So it is in the United States, where Trump does not play well in the San Francisco Bay Area or in New York City, but in the medium, small-town and rural preserves of the “unnecessariat.” We might also see the rise of Trump-style authoritarian populism in a disturbing global context, one that includes the ongoing advances of the far right in western Europe (France, Scandinavia, Austria and now Germany), in eastern Europe led by Hungary and Poland, along with Putin’s Russia, Erdogan’s Turkey and, most recently, Duterte in the Philippines.

It is perhaps remarkable that, in America’s supposedly “middle class” society, the white working class is being discussed and catered to as the ultimate arbiter of this election. So unprecedented are the politics of 2016 that mainstream ideology suddenly feels the need to talk openly about the working class it previously disappeared or took for granted. UAW bureaucrats and AFL-CIO blowhard president Richard Trumka scurry hither and thither to convince the union rank and file not to vote for Trump.

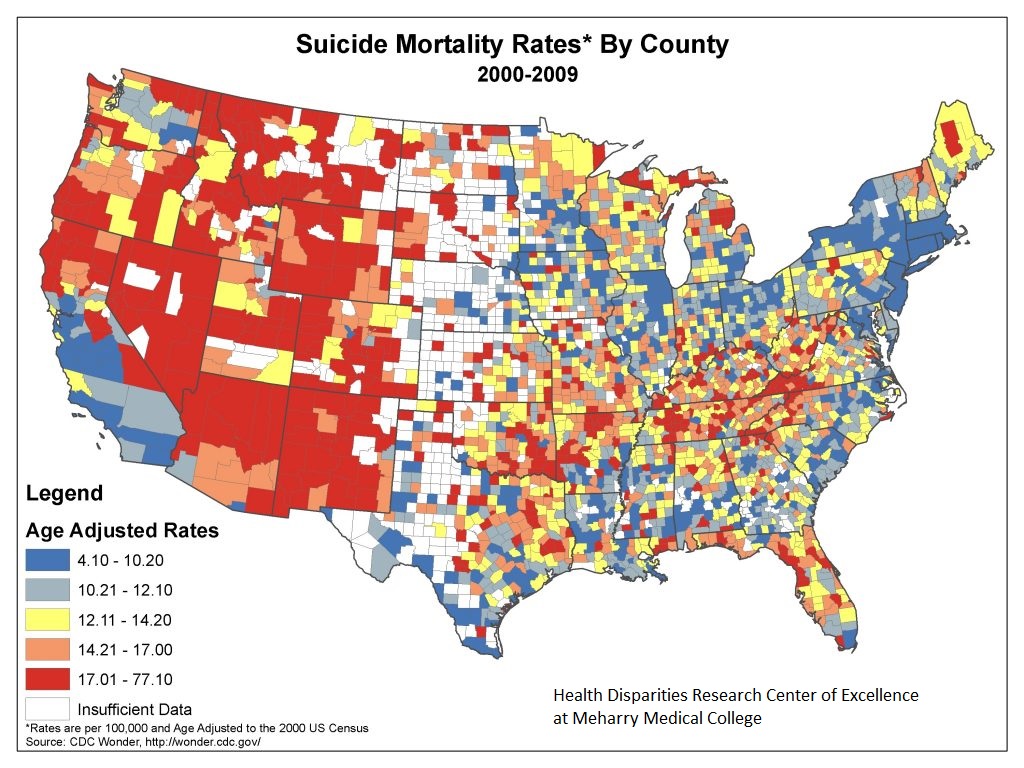

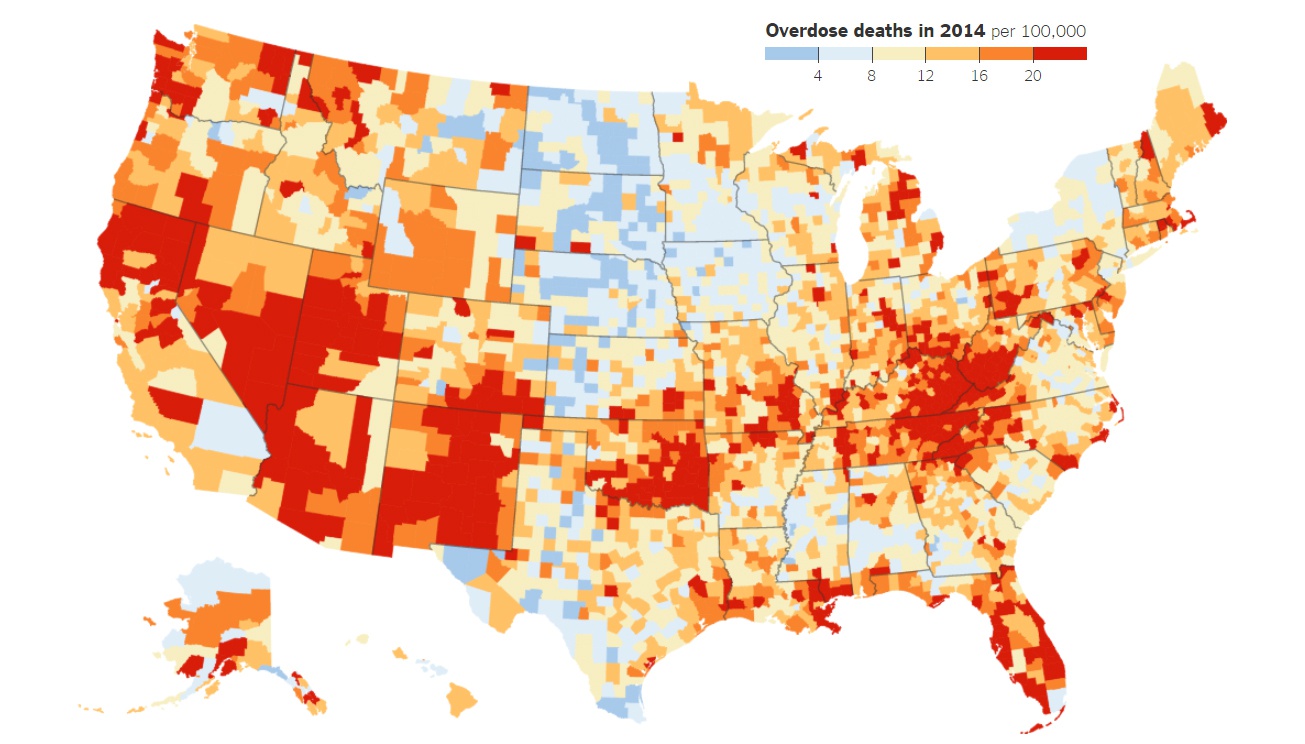

Trump, for his part, when able to stay “on message,” has made disarmingly lucid speeches about what has happened to workers in the decimated former heartland of mass industry, the key “swing states” of the Midwest. The hard-scrabble white working class of the former mass furniture industry in Virginia and North Carolina is also easy pickings for Trump, not to mention the West Virginia miners and ex-miners turned off by Clinton’s “green” agenda. And why should we be surprised, when the main surprising thing is that for the first time a candidate of a major party has bothered to talk directly to such workers about what has happened to them in the past decades, in contrast to the feel-good rhetoric of the Walter Mondales and Bill Clintons and now of Hillary Clinton? Saying “America never stopped being great,” as Hillary Clinton and the Democrats do, is already ideology run amok, and is even colder comfort to ex-industrial workers in the heartland, to a large swath of black people north and south, or to poor whites in Appalachia and elsewhere, currently subject to the highest death rates in the country by suicide, drugs and alcohol. We should not overlook, when identifying the class fractures at work, the role of identity politics, so rife in the metropolitan centers, in fueling the rise of Trump. Identity politics always had and has an explicit or implicit “suspicion” of workers qua workers, just as they have been supremely indifferent to the dismantling of the old industrial heartlands, which ravaged communities of white, black and brown workers alike. The rise of Trump is in part payback for the decades of condescension and barely concealed contempt for, or at best indifference to, the fate of ordinary working people rife in elite academia, the corporate media and the higher-end publishing world of the New York Times and posh journals of the chattering classes. Trump is a racist, you say? A misogynist? An immigrant and China basher? Yes, he is all those things, but these accusations from the garden-variety left and liberals do not get to the heart of his appeal as an “anti-establishment” figure. His apparent base does also have the highest per capita income of the major candidates and ex-candidates (Clinton and Sanders), indicating that he has forged a coalition of middle-and upper-class whites with some white workers and poor whites, itself rather unprecedented. All these groups have in common a conviction that the older America they knew is being replaced by an America with a blacker and browner working class, and multiple immigrant groups from East and South Asia, and from Latin America. Last but not least, Trump has indeed brought many elements of the far right, the David Dukes and gun-show crowd, into broad daylight, allowing them to emerge from the dark corners of the alt-right, and “freed their tongues,” as one of them put it, from the dominant “politically correct” atmosphere. Whether Trump wins or loses, such forces will not be going quietly back into their previous relative obscurity. To conclude, these advances of the far right and authoritarian populism around the world are the mirror of the failure of the moderate “left” which has collapsed into the happy family of center-right/center-left consensus of the past 45 years, led by the Tony Blairs, Francois Mitterands and Gerhard Schroeders in Europe and by the Jimmy Carters, Bill Clintons and Barack Obamas in the United States, and now joined by Hillary Clinton. Such forces are no stop-gap barrier, as many “lesser evil” theorists would have us believe, to the ascending right, but rather feed it, making it and not a serious left, of the type Insurgent Notes aims to help bring into existence, the apparent “anti-establishment” alternative to the status quo.

Comments

From Insurgent Notes #13, October 2016.

12 Men of Local 401

It’s fitting that the return of the trade union conspiracy trial would take place in Philadelphia, the city of the infamous Philadelphia Cordwainers Trial of 1805, the first known trade union conspiracy case in America. Beginning with the genesis of the first combinations of wage laborers in eighteenth-century England, trade unionism has been perceived and prosecuted as a conspiracy against private property—and rightly so. What is a trade union but a permanent conspiracy against private property and the inviolable right to private property? Engels designated trade unions as schools of war in The Condition of the Working-Class in England in 1845, and the processes underlying workers’ control and workers’ power made manifest in trade unionism then remain in operation today.

A car bomb erupts in the parking lot of the Pittston Coal Group’s Lebanon, Virginia headquarters in 1989. A scab UPS driver in Florida is stabbed multiple times with an icepick when he attempts to defend a delivery truck from having its tires punctured in 1997. Ten thousand tons of grain in Longview, Washington, are dumped from hoppers onto railroad tracks and rail cars have their brake lines cut by longshoremen in 2011. While the various sections of the political left were enamored with the promise of the September 2012 Chicago Teachers Union strike and its dissident rank-and-file leadership, community coalition-building and grassroots mobilizations, three months later over Christmas 2012, members of Ironworkers Local 401 in Philadelphia were sabotaging the active construction site for a Quaker Meeting House that was being built with non-union labor by cutting steel beams and bolts, setting fire to a crane and carving up set concrete with an acetylene torch.

Lacking all of the ideological pretenses of the Chicago teachers’ strike, the actions and fate of the Philadelphia ironworkers were ignored by all but labor’s enemies. According to the FBI, “the indictment charges RICO conspiracy, violent crime in aid of racketeering, three counts of arson, two counts of use of fire to commit a felony, and conspiracy to commit arson. Eight of the 10 individuals named in the indictment are charged with conspiring to use Ironworkers Local 401 as an enterprise to commit criminal acts. Joseph Dougherty, 72, of Philadelphia, the financial secretary/business manager of Local 401, was one of the eight individuals charged with racketeering conspiracy.”1 One night of sabotage in December 2012 garnered the full attention of the Federal government’s repressive apparatus.

Tools like wiretaps set in the union hall and bugging union officers’ phones, and the investigative resources of multiple Federal agencies were deployed against Local 401 of the International Association of Bridge, Structural, Ornamental and Reinforcing Ironworkers. Incidents of organized force and illegal tactics by the union going back to 2008 were documented, compiled and used to arrest two more men, for a total of 12 members and officers of Local 401 facing indictments. Conspiracy and racketeering were the centerpieces of the Federal prosecutor’s list of charges, which marked an epochal shift in America’s labor relations regime. Eleven of the 12 men took plea deals; seven agreed to turn state’s evidence and testify against the lone union member who refused to plead guilty: then–72-year-old Joseph Dougherty, Financial Secretary and former President of Local 401. Dougherty was tried and convicted on all six counts against him in Federal court and received a sentence of 19 years in prison and half a million dollars of restitution in July 2015.

While the acts of sabotage and arson against the Quaker Meeting House construction site was the catalyst for Federal intervention, the full menu of illegal tactics utilized by Local 401 over the years in pursuit of union objectives was necessary to use RICO in a novel, but predictable, way. The case against the 12 members and officers of Local 401 and the trial of Dougherty marks the final evolution of the narrative of labor racketeering. From focusing on the predatory schemes of organized crime and exposing organized crime infiltration of trade unions, to the illegal tactics of organized labor and the return of the trade union conspiracy trial.

The Clayton Act and Labor Racketeering

Exemption of trade unions from conspiracy laws was a demand featured in the original platform of the American Federation of Labor’s predecessor and precursor, the Federation of Organized Trades and Labor Unions of North America, at its founding convention in 1881. It wasn’t until the passage of the Clayton Antitrust Act in 1914 that juridical normalization of trade unionism was accomplished. This was the ascension of trade unions from clandestine to legal status in America, where they would no longer be persecuted and prosecuted as illegal conspiracies against private property and wage cartels obstructing commerce.

But a creeping problem emerged with the introduction of the word “racketeering” to the vocabularies of business and government. The word itself as it is used today is said to have originated with the Employers’ Association of Chicago as a means to describe the International Brotherhood of Teamsters in 1927. Accusations of racketeering became a functional doppelganger to redbaiting. Politicized trade unions were redbaited, while less politicized trade unions were charged with being dominated by gangsters. After the CIO purged its communist-led affiliates and amalgamated with the AFL in 1955, racketeering overtook redbaiting as the preferred ideological weapon against labor in the United States.

Beginning with the passage of the 1973 Racketeer Influenced and Corrupt Organizations Act (RICO), ostensibly non-partisan police search and destroy missions against organized crime routinely led to Federal judges installing puppet regimes in labor organizations in the form of Federal trusteeships and consent decrees, regardless of whether existing union officers were targets of criminal indictments, with union financial transactions, contract negotiations, the contents of union constitutions and even the ability to strike or engage in any form of concerted action all taken over by a government-appointed trustee. All of the expenses for anti-racketeering trusteeships (which often last for years) are paid for by union members. In the 1980s and 1990s, civil RICO suits and/or Federal trusteeships were deployed against nearly 20 labor organizations, the most important being the three International unions targeted by the Federal government: the International Brotherhood of Teamsters (1989), Laborers’ International Union of North America (1995), and Hotel Employees and Restaurant Employees International Union (1995). But in 2013–14 the police infrastructure built up and empowered to dismantle La Cosa Nostra was deployed against a local union without any connection to organized crime: the members and leaders of Ironworkers Local 401.

US v. Enmons

Congress passed the Anti-Racketeering Act, also known as the Hobbs Act, in 1934 to combat labor racketeering. It was worded in such a way as to give law enforcement the ability to arrest and prosecute gangsters who had infiltrated trade unions while explicitly preventing the Act from becoming a union-busting tool. Supreme Court interpretations of the Act exempted trade union demands from prosecution, even if such demands are objectively unreasonable and openly obstruct commerce. A 1973 Supreme Court case, US v. Enmons, expanded these exemptions for organized labor when it ruled that the Hobbs Act could not be used to prosecute union members and officers on Federal charges of extortion when they pursued lawful union objectives through illegal means. The case originated with members of International Brotherhood of Electrical Workers Local 2286 who were on strike against the Gulf States Utilities Company. A group of union members were hit with Hobbs Act charges for “firing high-powered rifles at three Company transformers, draining the oil from a Company transformer, and blowing up a transformer substation owned by the Company. In short, the indictment charged that the appellees had conspired to use and did in fact use violence to obtain for the striking employees higher wages and other employment benefits from the Company.”2 The Supreme Court ruled in favor of the workers, noting that collective bargaining is not considered an act of extortion under Federal law and thus does not present a predicate crime for prosecution under the Hobbs Act.

The underlying acts which prompted the recent spectacle in Philadelphia included filling locks with superglue, cutting steel beams and bolts, setting fire to a crane, beating non-union workers with baseball bats, slashing tires, verbally threatening sweatshop contractors and sabotaging construction equipment. In other words, the arrested ironworkers were using utterly vanilla expressions of organized force that were not unique to their organization, trade, industry or city. Collective bargaining by violence does not meet the definition of extortion under the Hobbs Act and falls within the US v. Enmons exemptions, leaving such illegal tactics to be prosecuted at the local level as isolated incidents, but episodes of organized force over a six-year period were documented and used to show a pattern of “racketeering” activity in Local 401 under the RICO Act, leading Federal agents and prosecutors to define the local union as a criminal enterprise even though the objectives pursued with illegal tactics were lawful collective bargaining objectives rather than the personal enrichment of union officers (the cornerstone of labor racketeering prosecutions under RICO). According to the Department of Justice, racketeering is not a necessary element for prosecution of Hobbs Act violations, but Hobbs Act violations can be used to demonstrate a pattern of racketeering activity for prosecution under the RICO Act. Dougherty’s trial was a racketeering case without racketeers, an extortion case without using anti-extortion statutes and a conspiracy case where the objectives and actions in question were explicitly exempted from the statutory definition of conspiracy.

Philadelphia Building Trades

As of 2012, the estimated composition of the local building trades unions was 99 percent male, 76 percent white and 67 percent who did not live in the city limits. When members of the laborers’ union (LIUNA) are removed from the sample, the racial composition skews further to 81 percent white.3 Affirmative action in the building trades unions originated in Philadelphia with the 1969 “Philadelphia Plan,” Lyndon Johnson’s executive order 11246—which established mandatory hiring guidelines for minority workers on government funded construction projects in the city through a quota system. It was a test case and later marketed as a model for the rest of the country to bring black workers into the skilled trades, primarily in metropolitan areas.

It was bitterly fought in court by the Contractors Association of Eastern Pennsylvania. At the 29th Convention of the International Union of Operating Engineers, General President Wharton reported, “Without the training provisions, the Philadelphia Plan was doomed to failure… The hard fact remains that there has been no significant increase in minority membership in the local unions covered by the Philadelphia Plan. Simplistic formulas are no substitute for trained mechanics and an equitable dispatching system.”4 Under his direction, the IUOE developed its own “Affirmative Action Plan” for its local unions in the Pennsylvania region which established an alternative means for increasing minority membership in the building trades and thus more skilled minority workers on construction projects: a change in union policy to drastically increase the number of minority apprentices. IUOE Local 542 in Philadelphia won Federal exemption from the Philadelphia Plan quotas on the basis of its internal plan, which largely became the model for the other building trades unions.

In a report on minority membership in the skilled trades in Philadelphia and specifically in Ironworkers Local 401 in 1995, a New York Times reporter inadvertently outlined the role of contractors in perpetuating white hegemony in construction: they are merely required to make a “good faith effort” to hire minority tradesmen, which often means simply making formal inquiries to the building trades unions who are responsible for supplying the labor pool. This situation was noted by an officer of a carpenters’ union district council:

Pulling a folder of letters from contractors out of the clutter on his desk, he says they all make the same request—that he refer qualified minority workers for possible employment in future projects.

“I have my secretary call them and ask how many minorities they want tomorrow and where to send them,” Mr. Coryell says. Do they ever request any?

In reply, Mr. Coryell summons his secretary, Maureen McGovern. “They all say, ‘Thank you, we’ll make a note of it,’ she said. “None has ever called back, and I have been doing this since 1981.”5

The same article gives the impression that IUOE Local 542 challenged the Philadelphia Plan in court as a kind of white resistance to black entry to the trade, when in reality the union was put in the position of being mandated to supply minority operating engineers who largely did not exist—leaving the union to formulate concrete means by which to change this. By the 1990s, Local 542 had a 21 percent minority membership; twp black members had been elected to the nine-member Executive Board and 30 percent of members dispatched to jobs from the hiring hall were minorities. Marc Halpern, a court appointed “outside expert” whose job it was to oversee the IUOE “Affirmative Action Plan” in Philadelphia in the 1980s–90s, concluded that the problem of minority tradesmen maintaining equal employment opportunity with their white fellow union members was a creation of the employers, the contractors, rather than the unions. This was the experience of a black member of Ironworkers Local 401, who noted that he would be dispatched from the hiring hall relatively often, but would be routinely laid off.

Another aspect of the problem was noted by the then-president of the AFL-CIO Building and Construction Trades Department Robert Georgine: “Minorities have been trying to enter the skilled trades just as opportunities have shrunk.” Apprenticeship programs administered by local building trades unions have been the practical means by which minority workers join the skilled trades. As economic recession or open crisis reduces the number, size and duration of available jobs, the labor pool controlled by the trade unions necessarily tightens to protect the integrity of the existing membership. Without apprenticeship opportunities, which require several years to complete, the racial composition of the unions becomes static. Ironworkers Local 401 is a product of this environment. A 2008 article from the Philadelphia Inquirer profiles the demographic history of Ironworkers Local 401 under Joseph Dougherty’s leadership:

Not only was this union nearly 100 percent white, but it was nearly 100 percent Irish, too – and not just any Irish either. Most members were descendants of immigrants from Newfoundland.

Now, the 804-member still-primarily-Irish local is one of the most diverse of the Philadelphia building trades. Now, 96 of the members are black and 19 Hispanic. Overall, nearly one in five members is from a minority group, according to data given to City Council.

Joseph Dougherty joined Local 401 in the 1960s, became local president in 1982 and has served in a variety of leadership positions ever since. Like IUOE Local 542, Local 401 signed a consent decree to increase minority membership by reaching out to minority communities to fill apprenticeship positions after facing the identical problem of having an all-white membership unable to dispatch minority tradesmen to construction jobs. But the ironworkers’ trade has a long established heritage of Native American workers entering the trade going back to the turn of the twentieth century—however, they are often highly mobile and follow large jobs around the country, taking out union traveling cards or local union work permits when entering another local’s jurisdiction (as of 2015 Local 401 charged $5.00/week for a work permit and $50.00 per transfer). One such ironworkers’ union member was a chief of the Onondaga tribe in New York, who Dougherty reached out to in an effort to convince mobile Native American ironworkers to relocate permanently to Philadelphia as members of Local 401 while simultaneously opening apprenticeships in the local to young Native American men. As of 2008, Local 401 had 36 Native American members. Like the experience of the carpenters and operating engineers, contractors shifted the blame for low minority participation to Ironworkers Local 401, and like the other trades the ironworkers, through Dougherty, were able to demonstrate that the low minority participation on publicly funded construction projects was due largely to contractor resistance, not union foot-dragging:

Applicants started by taking a test. Those who passed were put to work immediately. If they impressed the foremen and supervisors, they would be admitted to the apprentice program, when there was enough work to build an apprentice class.

The best got in—the rest had to wait, even if they were sons and brothers.

He said that he managed to increase minority numbers in the apprenticeship programs, but that it took additional nudging from the court to get contractors to hire the minority ironworkers his union produced.

The contractors told the judge that Dougherty wasn’t supplying minority workers. They didn’t know Dougherty kept daily records of available workers, noting whether contractors had requested minority workers. They also didn’t know Dougherty had shown the records to Judge Green.

“They were caught lying,” he said. “After that, I got more cooperation.”6

None of this denies the existence of racism among white members of the building trades, or the existence of structural racism in the systems running between union hiring halls, Project Labor Agreements (“checker boarding” where minority members are dispatched to PLA projects while white members work on projects without racial quotas), union and non-union contractors and construction employment itself. Local 401, like IUOE Local 542 and many other building trades unions, opted to replace the exclusive hiring hall system to allow contractors to directly hire union tradesmen when work was sparse. In practice, this allowed white union foremen to select who would be hired for jobs—generally other white members, often with familial ties. Black members of Local 401 have long struggled to win representation on the local’s executive board. However, Joseph Dougherty’s and Local 401’s record is nonetheless better than most.

Two Labor Movements

In a statement released after it was revealed that union members had sabotaged, vandalized, burned up their project, the local Quakers said, “Chestnut Hill Friends Meeting stands in support of the ideals and achievements of the labor movement, which strongly resonate with our long-held beliefs in the equality of all and the right of all workers to a living wage and safe working conditions, and with our testimonies of peace, integrity, and community,”7 and yet, when it was time to select a contractor to build their $8.5 million project, an opportunity to put this resonance of long-held beliefs into tangible form, they accepted the bid of a non-union contractor to save money.

But the labor movement is not an idea; it’s a social and physical fact. The Philadelphia ironworkers’ union implicitly recognized that the class struggles of wage labor against capital can’t be neutered and domesticated. It comes from a place where trade union discipline is derived from the legitimacy embodied in the local union leadership and where winning new and defending past material gains is not just a social but a physical struggle as well. Their tactics are a reminder that solidarity is not a moral choice but a material necessity, that words and ideas are worthless if they are not anchored in actions.

Three months before the Quaker Meeting House construction site in Philadelphia met an acetylene torch, Chicago teachers went on strike for eight days. The Chicago Teachers Union and its strike action represent all of the things that the socialist and progressive left finds appealing in the labor movement. Its leadership comes from a dissident reform and rank-and-file group called the “Caucus of Rank and File Educators” (CORE); it’s committed to a social justice or social movement program and emphasizes grassroots community partnerships through a diverse alliance of teachers, students, parents, taxpayers, politicians and others in a general defense of public education and delivering professional excellence. This is the kind of labor movement that groups like the Quakers in Philadelphia support. It’s the kind of labor movement that the government has been trying to foster with the carrot of legal protections and the stick of Federal regulations and law enforcement for decades.

But a trade unionism, which exists through government fiat, is not capable of standing on its own when precarious legal protections are removed. We came extremely close to witnessing the Wisconsinization of American public employee unionism nationwide with the recent Friedrichs v. California Teachers Association stalemate; a narrow miss due only to the unexpected expiration of Supreme Court Justice Antonin Scalia before he could render a vote on the case.

The reaction of Philadelphia’s trade unionists to the charges and Dougherty’s trial were mixed. Pat Gillespie, longtime Business Manager of the Philadelphia Building and Construction Trades Council AFL-CIO, was quoted in October 2014 as saying, “I’m saddened that people are in such a desperate state of mind that this kind of thing would be done… It’s kind of ironic. Do you know how many schools and churches the trades have built pro bono? It’s hard to count… And then they have a place of worship that’s desecrated before it’s even done? That’s just sad.”8 But after Dougherty’s conviction in July 2015 when local union members organized a support rally, Gillespie said he would, “be at the rally despite the image it may portray. If the rally is a rally to support Joe, then never mind the consequences.” The organizer of the rally, Jim Moran, an old timer in the Philadelphia labor movement, called Dougherty’s trial, “part of a corporate attack on unions.” These words became fodder for labor’s progressive allies at the media outlet Daily Kos, who had this to say about Dougherty, Local 401 and their supporters:

LABOR MEMBERS HOLDING SOLIDARITY RALLY FOR DOUGHERTY ON MONDAY! WHAT POLITICALLY – DUMB IDIOTS!

Is there anyone dumber than Jim Moran?

For union members to rally around such criminals as the 12 convicted members of the Ironworkers union aids and abets the right wing’s attacks on unions.

What is it about arson, violence, extortion, vandalism and threats to 8 and 11 year old children and a woman that union leaders Jim Moran and Patrick Gillespie find worthy of a public rally?

These idiots are handing ammunition to every right wing Republican opponent of unions.

Joseph Dougherty and the other 11 union convicted criminals should be condemned and shunned by anyone who truly supports all of the good things that come from unions.9

Daily Kos, it should be noted, routinely publishes exceedingly generous articles on the Chicago Teachers Union and has done so for years. Gillespie’s mixed public statements to the media are representative of a labor movement at war with itself. Since the dissident movements of the 1960s–70s like Steel Workers Fightback and Miners for Democracy, the AFL-CIO has moved further away from the workplace and sought to dilute labor’s ultimate leadership role to one in which labor has abdicated into just another constituent voice of the 99 percent, The People, and transparently accountable to liberal, progressive and community allies. The condemnations published by Daily Kos speak to the same impulse which led the AFL-CIO 2013 Convention to bring the Sierra Club, NAACP, National Council of La Raza, Mom’s Rising and United Students Against Sweatshops into more formal partnership with the labor movement while programs like Union Summer create a transmission belt for college and university student activists to become union staff members, replacing union structures derived from within union memberships.

Local 401 and the Chicago Teachers Union each represent the two combatants within every American labor organization: creating, building and maintaining organizations capable of extracting new and protecting past material gains extracted from employers, forming centers of resistance of labor against capital—and the contemporary pressures of non-violent passive resistance and civil disobedience, community partnerships and alliances based on the values of democratic-civil society at the foundation of social movements.

If the agency shop is banned, if the scope of bargaining is legislatively limited to wage increases, if public sector collective bargaining agreements are statutorily limited to 1 year terms—will there be another Chicago teachers’ strike, will there be a Chicago Teachers Union, will there be such gushing displays of social justice, community activism? With Wisconsin public sector unions as a guide, and their overnight starvation of two-thirds or more of their members and overnight evaporation of their basic functionality, the answer is a simple no.

The kind of labor movement we need won’t be hurt by legislative or judicial curtailment of bargaining rights, won’t be afraid to lose allies who give only verbal and not material support to organized workers, and won’t wilt under adverse political climates. That kind of labor movement, the kind we had when the Clayton Act was force fed to Congress, was dealt a major blow in a Federal courtroom in 2015. It’s terribly revealing that no one noticed. Something very fundamental to the socialist movement is in the hand that held the torch, swung the bat, slashed the tires, dumped the grain, blew up the car, stabbed the scab: the legitimacy of the officers who gave the order or led the union, the discipline to carry out any task or the initiative to take sides and to hell with the consequences, the genetically anti-democratic content of workers’ control and workers’ power, class discipline and class violence. Aside from questions of theory and practice, our conceptions of labor’s class struggles, trade unionism and the revolutionary movement, Joseph Dougherty deserves the same support as was given Mooney and Billings, Sacco and Vanzetti, Haywood, Pettibone and Moyer and the McNamara brothers. As much as this case reminds us what kind of labor movement we used to have, it equally reminds us what kind of socialist movement we used to have as well.

- 1Racketeering and Arson Charges Filed Against Members of Ironworkers Union, FBI press release, February 2, 2014, FBI archives.

- 2US v. Enmons, 410 US 396 (1973).

- 3“Despite pledges to diversify, building trades still mostly white males,” Axis Philly, June 10, 2013.

- 4Mangum and Walsh, Union Resilience in Troubled Times: The Story of the Operating Engineers, AFL-CIO 1960–1993, M.E. Sharpe: New York (1994).

- 5Louis Uchitelle, “Union Goal of Equality Fails the Test of Time,” New York Times, July 9, 1995.

- 6Jane M. Von Bergen, “One trade union’s road to diversity: How ironworkers surpassed other building trades,” philly.com, February 7, 2008.

- 7Simon Van Zuylen-Wood, “After Arson, Chestnut Hill Quakers Defend Labor Movement,” Philadelphia Magazine, January 23, 2013.

- 8MaryClair Dale, “Indictment: Pa. Ironworker Union ‘Goon Squad’ Committed Arsons, Intimidation,” NBC Philadelphia, October 5, 2014.

- 9“Why would Phila labor leaders help anti-labor agenda?” Daily Kos, July 19. 2015.

Comments

From Insurgent Notes #13, October 2016.

I hope this essay makes sense. It’s intended to enable those of us associated with Insurgent Notes and others to imagine how we might contribute to the emergence of an emancipatory, anti-capitalist mass politics in the aftermath of the 2016 presidential election. The most important point that I want to make is that no variety of liberalism, progressivism or social democracy will be adequate for addressing the multiple global crises of capitalist society nor will they be adequate for providing a genuine alternative to the many millions of people who are drawn to varieties of populist or fascist politics. Put simply, only a large, international, anti-capitalist and socialist movement can provide the alternative to capitalism the people of the world need and an alternative that can defeat the challenge of what I’d call revolutionary reaction.

A central task in the development of that movement is the expansion of people’s understandings of politics beyond participation in electoral politics. Such an expanded understanding would have few limits and would include sustained engagement with all of the aspects of people’s daily lives at work, in their communities, and in their personal lives. But it cannot allow that engagement to result in a subordination of a commitment to a revolutionary transformation for all to the amelioration of the conditions of some. In that context, international solidarity will be indispensable.

It will also require some new ways of thinking and acting about what it means to “do politics.” At the end, this essay explores some aspects of what such new ways might look like.

In spite of hours of work on it, the essay is not complete and it needs the ideas of others to make it so. More than anything, it’s an invitation to others to respond. I would welcome the opportunity to talk with individuals or groups about the document—to answer questions, to clarify confusions and to push beyond where I leave off.

These are its parts:

- Setting the Stage for 2016

- On Trump and His Supporters[1]

- On Sanders and, by contrast, Rosa Luxemburg’s Opposition to “War as Such”

- Resemblances to the Past

- The Almost Fifty Years’ Assault on the Working Class

- The Moment and a Response

- Core Principles of a Strategy

- A New Start for Revolutionary Political Organization

- An Earlier Conjuncture

- Doing Politics: Notes from an Earlier Moment

- What Insurgent Notes Could Contribute

Setting the Stage for 2016

We need to make our own distinctive sense of the reasons for and the significance of the breaking apart of the United States electoral system that Dave Ranney described as a “vehicle to keep American common sense intact and unchallenged.” In 2014, Ranney wrote: “A system of perpetual and increasingly expensive elections, two dominant parties that have programs well within the New World Order system, and a media that channels all political discourse into the confines of electoral issues combine to eliminate any serious challenge to the system itself. As a result, elections, far from being an exercise of democracy, are a form of thought control.”[2]

Later in his book, Ranney anticipated how this well-developed system of thought control might begin to unravel under the threat of a fascist movement. The potential for such a movement would be characterized by the following:

- Situated in context of new world disorder

- Total rejection of the current system

- Right-wing and conservative labels are not helpful

- Mass popular movement composed of a number of different classes

- Unification around notions of “superior people” and “living space”

- Exclusion of “inferior peoples”

- Mobilization around some imagined glorious past

- Order and discipline imposed by a powerful leader

- Belief in the use of violence by armed forces and police.[3]

Ranney commented:

Today’s crisis is a toxic stew that leaves society susceptible to fascist movements. That stew includes: paralysis of both capitalist private enterprise and governments; the inability of the new world disorder to generate enough value to keep the global system going; and an inability of the system to even sustain the people who live in it. These elements could breed a fascist movement capable of overthrowing and replacing the new world disorder. Increasingly, there are masses of unemployed and disaffected peoples around the world who will find considerable appeal in finding their identity as a part of a “special people” who need “living space,” and a life grounded in some glorious if mythical past.[4]

It’s not as if we shouldn’t have seen something like this coming; there have been rehearsals of it for many years. I’d suggest that all of the candidates below were precursors, of sorts, of the Sanders and Trump phenomena of 2016:

1964—Barry Goldwater;

1968—Richard Nixon, George Wallace & Curtis LeMay, Peace & Freedom;

1980—Ronald Reagan, David Koch running for VP on the Libertarian Party line;

1988—Pat Robertson, Ron Paul;

1990—David Duke running for US Senator from Louisiana;

1991—David Duke running for Governor of Louisiana;

1992—Pat Buchanan, Ross Perot;

1996—Ralph Nader, Pat Buchanan, Ross Perot;

2000—Ralph Nader, Donald Trump & Pat Buchanan (Reform Party);

2004—Ralph Nader, Howard Dean, Dennis Kucinich;

2008—Ralph Nader, Dennis Kucinich, Ron Paul;

2012—Ron Paul, Herman Cain.[5]

Looking back at this list, I’d note that the right-wing sparks and spurts have been of much greater consequence than the “left” variants. And, of course, the rise of the Tea Party movement gave clear evidence of something different brewing on the right. But before the Tea Party, and perhaps more significant than the Tea Party, were Pat Buchanan and David Duke.

In 1992, Buchanan ran in the Republican primaries against the sitting president, George H.W. Bush, and won 3 million votes. His platform included restrictions on immigration (and building a border fence) and opposition to abortion and gay rights. Buchanan eventually supported Bush but he used his appearance at the Republican Convention to give what came to be called the “culture war speech.” For him and for many of his supporters, there was “a religious war going on in our country for the soul of America.” On the other side of that war were the Clintons:

The agenda Clinton & Clinton would impose on America—abortion on demand, a litmus test for the Supreme Court, homosexual rights, discrimination against religious schools, women in combat units—that’s change, all right. But it is not the kind of change America needs. It is not the kind of change America wants. And it is not the kind of change we can abide in a nation we still call God’s country.

Like Trump, Buchanan thoroughly enjoyed making fun at the expense of the Democrats. Here’s an especially memorable line:

Like many of you last month, I watched that giant masquerade ball at Madison Square Garden—where 20,000 radicals and liberals came dressed up as moderates and centrists—in the greatest single exhibition of cross-dressing in American political history.

But what galvanized the Buchanan supporters was his fervent opposition to trade. Not long before, he had been a regular garden-variety free trader. But, and I think this is a real but, he saw the devastation being left behind by the abandonment of American industries (especially in the cities), and he seized upon it like a dog upon a bone. His nostalgia for a lost America is, I think, genuine and blinded—black folks never appear in his remembrance of things past; only the hard-working white folks count. But, and this is another real but, his version of what has been destroyed and lost needs to be reckoned with. We’ll get back to Buchanan in a moment when he makes another appearance on the electoral stage in 2000.

For the moment, though, let’s turn to David Duke—who believes he has been given a new lease on life by the success of the Trump campaign thus far; in 2016, he’s now running for Senator from Louisiana. His earlier efforts to win high-level offices (in 1990 and 1991) were beaten back only through an intense mobilization of those who opposed him but revealed the extent of support he had among white voters—at least in Louisiana. Leonard Zeskind of the Institute for Research on Education and Human Rights has described Duke this way:

David Duke has been an ideological national socialist all his adult life. (Remember that the real name of Hitler’s Nazis was the National Socialist German Workers Party.) Before he became a Klansman, he was a junior national socialist, even marching around the LSU campus wearing a brownshirt uniform with a swastika armband once. His Klan…was a “nazi” Klan. He quit his Klan in 1980 and it has been 36 years since David Duke was a Ku Klux Klan member.

….

Mr. Duke is no longer the premier white nationalist movement leader that he once was. Others have emerged to push him into the second-tier ranks. It is a mistake, however, to discount his campaign. In this year of the “angry white male,” a significant stratum of white voters could be available if he asks for it. With 24 candidates in the primary, Mr. Duke needs a relatively small number of voters to push him into the run-off.[6]

Of special importance in this sorry tale is the brief entry of none other than Donald Trump into the primary process of the Reform Party in 1999―2000. The Reform Party was the odd child of Ross Perot’s third party campaign in 1996. By 1999, the party had splintered and, after a long song and dance, there were two possible candidates—Trump and Pat Buchanan (again!). A decade and a half ago, Trump’s powers of political perception were much greater than now and he called Buchanan out for being an anti-Semite and an admirer of Hitler. Truth be known, the Reform Party of that year was a strange creature. Trump kind of got it right when he said: “The Reform Party now includes a Klansman, Mr. Duke, a neo-Nazi, Mr. Buchanan, and a communist, Ms. Fulani.”[7]

Also worth noting in historical perspective is the sustained popularity of right-wing talk radio hosts (like Hannity, Limbaugh, Levin and—hard as it is to believe—the even more repulsive Michael Savage), Fox News and an array of social media news outlets (such as the Drudge Report established in 1995 and Breitbart established in 2007), the continued popularity of opinion makers like Pat Buchanan and Ann Coulter, the arrival of the conspiracy right (exemplified by Alex Jones’s infowars), and so on. My point is that the Trump moment is and continues to be the emergent result of a whole bunch of internally contradictory projects. But, we need to appreciate that they were all political projects—efforts intended to change the way that people thought and acted.

Ironically, perhaps no one can take more satisfaction with how things have worked out than Pat Buchanan—as was headlined in a recent op-ed, “Trump Stole My Playbook.” This turn of events reminds me of the fate of what were called the “anti-Semitic” parties that arose in Germany in the 1870s and gathered considerable support. Their electoral successes were short-lived and they all but disappeared as distinct organizations. At the time, some commentators thought that their views were little more than a brief hallucination. But it was no hallucination. The parties disappeared because there was no longer any need for them by the turn of the century—their views on the Jews had become all but completely accepted by all of the organized political parties, including the leaders of the Social Democrats (with the noteworthy exception of Rosa Luxemburg).[8] The proof of this powerful cultural absorption into the core assumptions of German political culture of what had been a political heresy, if not joke, was the relative ease with which the Nazis’ anti-Semitism became widely accepted after World War I. As I’ll get to below, there’s an even more dangerous version of Buchanan waiting in the wings of the Trump campaign today.

While it makes some sense to link the Trump and Sanders phenomena as a way of estimating the extent of the electoral upheavals in 2016, the differences between their respective campaigns deserve attention. Perhaps most important is the very different relationship between each candidate and his bases of support. While both candidates tapped into what had been a not quite visible level of deep discontent with politics as usual, their campaign activities had little in common. What Sanders more or less did was to put forward a set of rallying cries around a set of progressive measures (progressive especially in comparison to what Clinton was saying through much of the primary season) and enlist supporters in relatively traditional activities—contributing money, attending enthusiastic, but orderly, rallies and serving as campaign workers (making phone calls, knocking on doors, leafleting prospective voters).

On Trump and His Supporters

It was quite different with Trump—for all practical purposes, there has been only one activity for Trump supporters, apart from voting—attending rallies, rallies which often enough could as well be understood as white mobs. See, for example, the video of scenes from a number of different Trump events across the country posted on the web page of The New York Times in early August of 2016.[9] Hard as it is to believe, it seems evident that Trump’s rhetoric from the stage is at times quite tame in comparison to that of some of his supporters. There is more than a little about mob behavior that’s evident among some Trump supporters.

Mobs have loomed large in the ways in which white folks have come together to deprive blacks of their freedom and rights—the nightriders after the Civil War, the lynch mobs of the Jim Crow era, the attackers of students attempting to desegregate high schools in the 1950s and 1960s. During the Civil War, Karl Marx had noted “the abject character” of the poor whites and that characterization proved true long after the war was done.

But lest we miss something important, while the attractions of the mob have won out far too often, there were exceptions. By way of example, the recently released movie titled The Free State of Jones shines light on an all but completely forgotten moment during the United States Civil War—when miserably poor whites in Mississippi made common cause with runaway slaves to defy the Confederate and Northern powers and began to build a free state.[10] What in the world happened? I’m not going to answer the question. Watch the movie, and maybe read the review I’ve referenced, and then we can talk. I will say that while people are seldom talked into changing their minds, new circumstances can create new possibilities. In that context, it would be very helpful to develop ways of thinking that can become practical truths that drive what people might do—given the right set of circumstances.[11]

We need to appreciate the complexity of the support for Trump so we can avoid rather simple-minded notions that what we have to do, for example, is to “Stop hate!” Over the last couple of months, I have read plausible accounts of the characteristics of Trump supporters that are all but completely contradictory. His supporters are, variously, mostly people out for the entertainment value of a spectacular event; people who have seen their towns and small cities all but disappear as companies left; people who see no place for themselves, ever, in the world around them; and men who still aspire to the Hugh Hefner Playboy life style and are stuck with what they consider to be a bad substitute. I’m sure that there are other equally useful and limited characterizations.

I suggest that we assume that they’re all right. Each captures a slice of the complex composition of the Trump alliance. It would be helpful to get to some understanding of what holds them all together. Tentatively, and not so terribly originally (not surprising in a year when there are dozens, if not hundreds, of Trump interpretations offered everyday in newspapers and on cable TV), I’d argue that his supporters are:

- worried about the security of their relative well-being because they don’t have the credentials or family connections that would allow them to survive another 2008 meltdown of the economy;

- worried about their own personal and family safety because of a steady diet of warnings about terrorist threats (see, for example, this security-system TV ad) and deep-seated fears of the dangers posed by real or imagined criminal elements;

- inclined to be very respectful of the authority and authoritative views of law enforcement personnel of all sorts (if they are not law enforcement officers themselves or family members of those officers);[12]

- significantly influenced by the sense-making of right-wing talk radio, web-based news media and Fox News;

- in the case of the men, more than a little bit influenced by a notion that “we’re not going to allow them to kick us around any more.”

But at the end of all that, they still come in many different flavors—some will vote for the remnants of a conservative platform that Trump barely espouses (Paul Ryan kinds of people); some feel that they have no choice in light of a Hillary Clinton campaign that all but completely represents the continuation of business as usual; many are really angry about what has been going on and want someone to do something to stop it; some are convinced that the blacks “are getting everything,” and some are self-conscious reactionary revolutionaries.[13]

There may be others still.

There seems to be little evidence that Trump’s supporters are overwhelmingly people who have been victimized by industrial downsizing (although they exist).[14] There may very well be people who think that they should be doing better than they are—as do most of us. There also seems to be a lot of evidence that he has many more men backing him than women and that is a fact worth reckoning with.[15] And then, most important of all, there are the whites—cutting across virtually every other category of support for Trump. If nothing else, Trump is a white movement—notwithstanding his small assortment of black supporters.[16]

In the background of the Trump campaign, there are two developments related to the white character of his campaign worth recognition for the dangers they portend. On the one hand, there is the coalescence of a fairly broad variety of white nationalist leaders who have made common cause in their support of the Trump campaign. A main vehicle for that coalescence is the American Freedom Party. Its very up to date web page includes articles by a who’s who of white nationalists and re-postings of columns by Pat Buchanan and Ann Coulter. At the same time, The Occidental Observer, a white nationalist intellectual site edited by Kevin McDonald, a retired professor from the California State University system, has emerged as a significant source of analysis of the influence of white nationalists on the Trump campaign and on the development of a self-conscious strategy to see beyond the election.

At the end of August, Clinton delivered a harsh attack on the involvement of the alt-right in Trump’s campaign; she didn’t go very far. Specifically, she completely left out any explanation for why it was that “fringe elements” were gaining a growing audience. She did not acknowledge the possibility or likelihood that steadily worsening material conditions, and the threats they appear to pose to lots of people, might have anything to do with the development of far-right movements. It’s not surprising since, after all is said and done, the economic policies advanced by Clinton I, Obama, or Clinton II are more or less the same—advance the advanced economy (meaning technology plus finance) and figure out how to control the rest (by carrot or stick). By way of comparison, Trump’s policies promise a return of good jobs for the millions of ordinary folks who can’t really touch high-paying job sectors.

Truth be known, neither Clinton nor Trump will be able to do terribly much to affect where investment capital goes or who will benefit. They can grease some wheels rather than other ones but they will not get to pick the wheels. On the other hand, either one of them will have a great deal of political and military power—power that is more or less awful for the people of the world. Those on the left who are enamored with Clinton’s more polished explanation of how she would wield that power, as opposed to Trump’s blundering, will all but certainly be terribly disappointed (but maybe not) with what she will do. She, like Obama, will launch murderous drone attacks across the global war-scape and continue his all too willing arming of Israel and other supposed allies in the Middle East. The results will very well be more Gaza’s and Syria’s, more deaths, more maimed children, and more refugees (who, like the European Jews of the late 1930s and 1940s, will search the world for places that will let them in).

More importantly, Clinton’s approach is opposed to an insurgency from the left as much as it is to one from the right. It is our terrible failing that, by way of comparison, we on the radical left pose no threat at all and we don’t even merit a mention in her attack. For too long, the mainstream left has been preoccupied with making its politics agreeable—with virtually no real uptake—until the Sanders campaign. Meanwhile, a radical left has barely existed outside of the sectarian groups that use a vocabulary that is all but meaningless for most ordinary people (for examples across the sectarian spectrum, see the Spartacist League, the Revolutionary Communist Party, and endnotes, or is understandable only when it effectively represents a betrayal of principle (see, for example, the International Socialist Organization (ISO)).[17]

Through all this, there has been both deep continuity and substantial change on the right. It may be that the changes (around matters such as defense of homosexual rights against Islamic attacks) have made the realization of aspects of the continuity (such as the establishment of the legitimacy of a European or “white” people with legitimate group rights within the US) more politically feasible.

In spite of the crazy ups and downs of the Trump campaign thus far (end of September), I think that it’s possible, and maybe even likely, that a crystallization of Trump’s messages might still be articulated and will meet with a positive response (especially in the context of the ongoing miseries of the Clinton campaign, grounded, as they are, on the essential truth of the matter—that Hillary and those she represents benefit from virtually every aspect of the current state of affairs and want to maintain it, while pretending otherwise). The headlines of Trump’s messages would be:

- Unfair trade is ruining America

- Uncontrolled immigration is also ruining America

- Terrorism is a danger that must be obliterated

- Law and order must be preserved

- America is weak

- America is over-engaged overseas

- The political and media elites control the country

- Those elites rely on hypocrisy and corruption for their continued power.

And truth be known, as a friend pointed out, there is a small spot in the back of all of our revolutionary brains that wants Trump to win—in part because he makes mincemeat of all those who defend the “consensuses” that result in:

- trillions of dollars wasted on wars, in thousands of members of the American armed forces dead and many more wounded—including those who wind up in TV ads for the “Wounded Warrior Project” scam[18] or as props for politicians seeking votes by insisting on how much they care about Veterans’ Administrations hospitals—and, worst by far, in many hundreds of thousands of people from other countries who have been killed or maimed and millions more forced into fleeing from the killing fields that their countries have become during more than thirty years of continuous war;

- the inevitable elimination of jobs and the destruction of communities, small and large, by the all powerful movement of the markets and the inevitable forward march of technological innovation (made tangible by containerization and robotization).

On Sanders and, by Way of Contrast, Rosa Luxemburg’s Opposition to “War as Such”

The Sanders phenomenon clearly represents something much more hopeful. More than twelve million votes for someone prepared to be identified as a socialist in a one-on-one against arguably the most powerful Democratic Party politician in recent times hint at the possibility of a mass socialist movement that might overcome capitalism. Needless to say, changing votes into mass political activity beyond voting will be no easy task.

At the same time, the fairly obvious weaknesses of the Sanders campaign when it comes to US world domination and military engagements pose additional obstacles to the transformation of the genuine accomplishments of the Sanders moment into something that goes beyond it. To be more precise about this matter, it is more or less obvious why Sanders steered his campaign the way that he did (systematically avoiding any substantive engagement with the realities of the American empire); he wanted the votes of those who wouldn’t be willing to do the same. What’s less clear is the extent to which Sanders supporters themselves share their candidate’s reluctance. If they, like many more before them, are willing to embark on a “political revolution” that’s built upon the defense of the interests of American workers and the broader population at the expense of people around the world, their “revolution” will prove to be an empty one—one that will only harden the chains that keep people within the system that imprisons them.

In the wake of Sanders’s endorsement of Clinton and the months since (with Sanders’s quite limited participation in the Clinton campaign—either because of his preferences or, more likely, hers, as she “pivots,” in that memorable word from the 2016 campaign, to the right), it is not at all clear what will be left of that Sanders moment. The political organization intended to carry the Sanders movement forward, Our Revolution, appears to have gone off the rails before it got on them (read about the staff revolt within the new organization, and for an overly friendly criticism, see Michael Albert’s open letter).

What is clear is that the Clinton campaign is making every effort to consolidate the Democratic Party as the one real capitalist party—by which I mean a party with an unequivocal commitment to serving and preserving the national and global interests of the owners of capital and of the nation state that remains the most powerful guarantor of the existing state of affairs. (Those are the interests that she presumably addressed in her speeches to Goldman Sachs.) Let me be clear—this does not mean that Clinton will offer no programs designed to win the support and the votes of many millions of poor and working class people. In order to win and to rule, a central task of those seeking election to positions of great power remains the cultivation of the confidence and hopefulness of large numbers of those being ruled. In spite of the rightward turn of her campaign messages, Clinton will continue to make much of her support for a party platform that incorporates many of the demands of the Sanders campaign for various domestic reforms.

At the same time, though, she will be attempting to secure broad support for continued aggressive US military involvements across the globe—most importantly, in southwest Asia, the Middle East, North Africa, Eastern Europe and the Far East. These involvements pose a great danger of more prolonged and more explosive wars. This is the light within which we should view the celebratory patriotism of the Democratic Convention and especially the staging of the much-heralded speech of Khzir Khan attacking Trump’s anti-Muslim stances resulting in widespread applause for him and his wife as “Gold Star” parents (parents who have lost a son or daughter in combat)—both at the Convention and beyond it.[19]

The speech was orchestrated so well that it seemed inconceivable that Trump would not be cowed. Needless to say, he was not and he came up with ways of attacking the couple’s integrity. However, perhaps more significant than Trump’s own response was the curious response of Trump supporters to a mother of a current soldier who spoke at a campaign event for Mike Pence. They cheered when she said that she was a mother of a serving soldier but jeered when she challenged Pence to distance himself from Trump. This suggests that some Trump supporters retain a strong sense of affection for people in the armed forces and veterans but are not willing to allow that support to drag them into support for the military adventures launched by the country’s political and military leaders. The John McCain option of unqualified support for the warriors and the wars may be becoming obsolete among a population that was long assumed to be endlessly available for both purposes.

All this confirms the need for a consistent anti-war and anti―world domination position as an essential element of a challenge to Clinton and the Democrats. There was an encouraging moment at the Democratic Convention when chants of “No more war!” erupted from Sanders supporters during the speech of Leon Panetta (the former Director of the CIA and Secretary of Defense), where he was praising Hillary’s determination and willingness to pursue military options.

In 2015, the United States deployed its military forces in at least 135 countries—ranging from specific targeted missions to long-term engagements. Recently, the Pentagon confirmed that the United States had 662 military bases of one kind or another in 38 nations (a good number of them encircling what are at times portrayed to be its most serious adversaries—Russia, China and Iran). Its warships and warplanes patrol the oceans and the skies and add emphasis to the warnings that are embedded in its military bases. It is a monstrous force, bearing comparison with one or another of the great armed nations in George Orwell’s 1984 or, perhaps of greater relevance to an audience in 2016, the empire in the Star Wars movies. The only defensible thing to do is to tear it down and make it impossible for it to be built again anywhere. But alas, many will say that such a move will enable some really bad folks to take advantage. Truth be known, none of us should be inclined to think that a defense of the Russian, Chinese or Iranian regimes is a good starting place for thinking about how to fight against the United States military monster. We have an unusual claim to make and we challenge those who dismiss it to make a better one.[20]

What’s needed is not “America First!,” but rather international solidarity with all of those who are exploited or oppressed by the current state of affairs. A writer at the Tampa Bay Communist League has brought the wisdom of Rosa Luxemburg to our attention:

Rosa Luxemburg, three times a minority as a Jewish-Polish woman in Germany, rose to international prominence by issuing the definitive Marxist statement regarding the war [World War I] from prison:

This war’s most important lesson for the policy of the proletariat is the unassailable fact that it cannot parrot the slogan Victory or Defeat, not in Germany or in France, not in England or in Russia. Only from the standpoint of imperialism does this slogan have any real content. For every Great Power it is identical to the question of gain or loss of political standing, of annexations, colonies, and military predominance. From the standpoint of class for the European proletariat as a whole the victory and defeat of any of the warring camps is equally disastrous.

It is war as such, no matter how it ends militarily, that signifies the greatest defeat for Europe’s proletariat. It is only the overcoming of war and the speediest possible enforcement of peace by the international militancy of the proletariat that can bring victory to the workers’ cause. …Proletarian policy knows no retreat; it can only struggle forward. It must always go beyond the existing and the newly created. In this sense alone, it is legitimate for the proletariat to confront both camps of imperialists in the world war with a policy of its own.

…But to push ahead to the victory of socialism we need a strong, activist, educated proletariat, and masses whose power lies in intellectual culture as well as numbers. These masses are being decimated by the world war. …The fruits of decades of sacrifice and the efforts of generations are destroyed in a few weeks. The key troops of the international proletariat are torn up by the roots.

…This blood-letting threatens to bleed the European workers’ movement to death. Another such world war and the outlook for socialism will be buried beneath the rubble heaped up by imperialist barbarism. …This is an assault, not on the bourgeois culture of the past, but on the socialist culture of the future, a lethal blow against that force which carries the future of humanity within itself and which alone can bear the precious treasures of the past into a better society. Here capitalism lays bear its death’s head; here it betrays the fact that its historical rationale is used up; its continued domination is no longer reconcilable to the progress of humanity.

The world war today is demonstrably not only murder on a grand scale; it is also suicide of the working classes of Europe. The soldiers of socialism, the proletarians of England, France, Germany, Russia, and Belgium have for months been killing one another at the behest of capital. They are driving the cold steel of murder into each other’s hearts. Locked in the embrace of death, they tumble into a common grave.

We need to stop comparing Bernie Sanders to Hillary Clinton. Instead, we need to compare him and ourselves to revolutionaries like Rosa Luxemburg or, closer to home, Wendell Phillips. At the same time, we need to recall and reclaim a mostly lost legacy of class struggle as the road to world peace:

The political meaning of the concept of exploitation is the most radical denial of capitalist legitimacy. This forced the workers’ movement to adopt internationalism as its main political doctrine which—in modern conditions—is also a denial of institutionalized political power (the nation-state) as well as a rejection of property and of the (patriarchal) family. It tends to be forgotten, but it was quite clear to everybody around 1900 that internationalism was a radicalization of the idea of perpetual peace, as it tends to be forgotten, too, that perpetual peace was a revolutionary idea. The official teaching was that civil war (revolution) was illegitimate, but war legitimate. Socialism had taught the opposite of that. Global class struggle would create perpetual peace, as the agent of war (the supreme coercion), the state, will be dead. Even today, if there would be tens of millions of people believing this, the powers-that-be would be frightened. One needs to have a little historical imagination to picture how this kind of “godless communism” affected those stable, conservative, puritanical, diligent, respectful, hat-raising societies of the late nineteenth century.[21]

Resemblances to the Past

In recent discussions, Loren Goldner has suggested that the period we are entering might resemble the early 1960s—exemplified by the interconnection between the Southern Civil Rights movement and the nascent New Left. I suggested, a bit differently, that a comparison might be made with the moment after the election of Lyndon Johnson in 1964 and the almost immediate escalation of the war in Vietnam—leading dramatically and, incredibly quickly, to an explosive growth in the numbers of people in SDS and other groups and to their radicalization (including a break with the Democratic Party and, more broadly, with an orientation to electoral politics).

We synthesized our views in a recent Insurgent Notes editorial:

The current period reminds us, in a bizarre way and in much more dire circumstances, of the early 1960s. Then as now, an idealistic new generation was awakening to politics. Then as now, in both the nascent New Left and early civil rights movement (both deeply interconnected in the Jim Crow South) and today after Occupy and Black Lives Matter, something got out of the bottle that will not easily be put back in. We insist above all, where the potential role of our marginal milieu as conscious communists is concerned, that small groups do not shape consciousness, events do. Events for the 1960s were the later years of the southern civil rights movement, the war in Vietnam, the radicalization of black people after the civil rights movement hit a wall, and the rank-and-file and wildcat upsurge in the United States working class. By the late 1960s, some many thousands of young people coming out of the New Left and the Black Liberation Movement had declared for revolution, and many joined groups organizing for it. It did not end well, for reasons that we cannot do justice to here.[22] For the most part, the emerging revolutionary movement was dominated by either Stalinist/Maoist/Trotskyist sects or by groups well on the way to embracing an all-purpose, and hardly anti-capitalist, “progressive” politics. A not insignificant part of the black left turned towards nationalism. And a small part of what might be considered the middle-class white left was drawn into the substitution of terrorist violence for politics. Little of consequence is left of all of it although, to be fair, Sanders’s current vision has more than a little in common with the above-cited progressive politics.

Let me be explicit. What was missing as the 1960s ended was a substantial and self-conscious revolutionary and emancipatory bloc that rejected Leninism-Stalinism-Trotskyism-Maoism. What might have provided the basis for such a bloc was a new synthesis of libertarian communism (opposed to all of the miseries of supposed socialism in the Soviet Union and its copycats in places like eastern Europe, China, North Korea and Cuba and grounded in a “new reading” of the works of Karl Marx) and anarchism. The remnants of the earlier small groups that might have provided the basis for the development of such a bloc were not ready for the challenge. I’m thinking of groups such as the Johnson-Forest Tendency, News and Letters, Root and Branch, the people around Murray Bookchin, the League of Revolutionary Black Workers, etc. It didn’t help much that individuals in these groups were inclined to spend more time competing with each other than seeking common ground with those in other groups.[23]

As I look back at the period, what seems evident is that the turn to the working class by a good number of ex-student radicals as the potential driver of revolution was not accompanied by an equally serious turn to the work needed to understand exactly what capitalism was up to. By way of a small personal recollection, when the study groups of the Taxi Rank & File Coalition, that I was active in for the better part of the 1970s, were initiated in the early 1970s, the readings of Marx were almost entirely limited to Value, Price and Profit and selected excerpts from some of his other works. Recently, I have come to realize that Value, Price and Profit was a better work than I thought at the time but it remains the case that the engagement with Marx was quite limited for many genuine radicals (see more about my re-reading below).

Keep in mind that, at the time, the Monthly Review folks were quite hegemonic in advancing their Marxism for modern times and the Maoist Guardian newspaper was arguably the most influential voice of supposed revolutionary politics. But it was not completely dreary—this was also a time when Radical America, Liberation, New Left Review, Race and Class, the first New Politics, as well as perhaps hundreds of local radical newspapers, supported by a remarkable national news service (Liberation News Service), provided some balance and alternative interpretations.

To back up a bit, in 1968, with the war in Viet Nam raging and, unlike now, scenes of dying US soldiers and Vietnamese soldiers and civilians filling the TV screens night after night, the energy of great numbers of young people was drawn into the campaigns of the peace candidate, Eugene McCarthy, and a bit later, Robert Kennedy. (I should know—I was one of them and think I might even be able to dig out the articles I wrote for my college newspaper about why). What I want to emphasize is the very uneven and relatively long-term processes of radicalization that were in play even in the context of a quite explosive historical context. I think it’s likely that the same pattern will be evident now—although the background context of profound world economic crisis and increasingly murderous conflicts across the globe, as compared to a somewhat localized imperialist war, could make a difference.