Contents from this issue of the journal.

Introduction

We are pleased to present the new issue of Insurgent Notes.

As has been our practice for most recent issues, the contents include articles that have been previously posted on the website since our last issue was published in May, as well as new ones.

Three of the previously published articles are reviews of Loren Goldner’s collection of essays titled Revolution, Defeat and Theoretical Underdevelopment: Russia, Turkey, Spain, Bolivia—published by Haymarket Books. The three reviewers are Dave Ranney, Wayne Price and S. Artesian.

In addition, Loren Goldner has himself contributed a review of a new book on the profound and all but entirely distressing results of several decades worth of “development” in the San Francisco Bay Area.

We’ve associated two quite different articles in a section titled “Political Notes” because they speak directly to the current situation in the United States. Matthew Lyons analyzes the ways in which the “alt-right” has been set back in the last year and the ways in which they are attempting to figure out what to do next. Don Hamerquist explores the reasons why the revolutionary left has been unable to take advantage of situations and circumstances that would appear to have been quite promising.

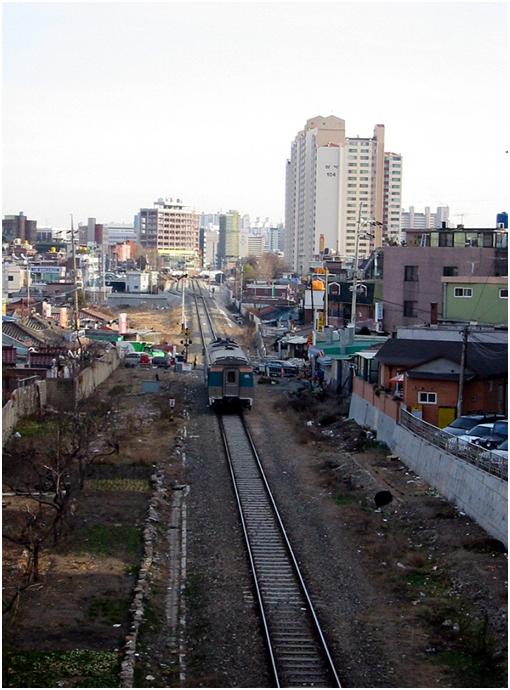

We have a number of previously posted reports from around the world—Iran, Mexico, Vietnam and Korea (all previously posted) and one new report on Costa Rica.

Finally, we’re publishing a new essay by John Garvey that is a revised and expanded version of remarks he made at a panel discussion on “What is Socialism” in early September of this year.

We’d like to alert readers to our plans to publish a number of articles in the months to come on the occasion of the hundredth anniversary of the German Revolution of 1918 and the assassinations of Rosa Luxemburg and Karl Liebknect in January 1919. We will not forget!

David Ranney reviews "Revolution, Defeat, and Theoretical Underdevelopment: Russia, Turkey, Spain, Bolivia" by Loren Goldner for Insurgent Notes issue 18, October 2018.

NB: The book itself is available on Libcom here.

The title of Loren Goldner’s latest book, Revolution, Defeat and Theoretical Underdevelopment (Haymarket Books, Chicago, Illinois, 2017) aptly sums up the basic thesis. What links his four case studies of the 1917 Russian Revolution; the experience of the Turkish Communist Party with Russia and the Communist International between 1917 and 1925; the failings of the revolutionaries in the Spanish Revolution and Civil War between 1936 and 1939; and the failure of the Trotskyist Fourth International in the Bolivian Revolution of 1952, is what he terms “theoretical underdevelopment.” None of these revolutionary movements were able to fulfill their promise of a new socialist society. And Goldner makes the case that the lack of a clear theoretical basis that could chart a direction forward was partly responsible for the failures.

In the case of the Russian Revolution, Goldner correctly focuses on the opportunities missed by underestimating the revolutionary potential of the peasantry. Peasants, at the time of the revolution, constituted 90 percent of the population. And 98 percent of them had organized production in the form of communes known as the mir. Furthermore, the peasantry had shown itself for generations to be militant revolutionaries. But there were elements in the revolutionary socialist movement inside of Russia that failed to see the possibilities of a path to socialism based on the mir itself. Instead, the dominant view was that Russia must go through a stage of capitalism to get to socialism. This had been debated in Russia during the time of Marx who, in the last decade of his life, was studying Russian agriculture and alternative paths to socialism. He argued with those who posited the need to have capitalism first that if this was Marxism that he was not Marxist. But after Marx’s death, Engels suppressed much of this work. And Lenin adopted such a stage theory before and after the Russian Revolution. His stance eventually opened up the door to Stalin after Lenin’s death to engage in a mass collectivization of agriculture that destroyed the mir and institutionalized the revolution in a state capitalist form.

This failure was compounded by Russia’s stance in Turkey after World War I. Goldner’s title for his chapter on Turkey is “Socialism in One Country before Stalin and the Origins of Reactionary ‘Anti-Imperialism.’ ” He traces the revolutionary movement in Turkey between 1917 and 1925 when Lenin’s Russia and the Third International chose to support the regime of Mustafa Kemal, known today as “Attaturk,” who had put an end to the Ottoman Empire, over a vibrant revolutionary communist movement that was also active in the region. Kemal had been successful in kicking Greece, which was supported by the British, out of Turkey. But there were soviet-style revolutions throughout what we today call the “Middle East.” Even Trotsky chose the “anti-imperialist” Kemal regime over these movements. In fact two months after the Turkish Communist Party leadership was massacred by the Kemal regime, Lenin signed a trade agreement with Kemal’s Turkey, making it clear that Turkish communists and all the other revolutionary movements in the region would not have the support of the Russians. A narrow focus on a regime intent on constructing first capitalism and then socialism took precedence over possible revolution in the East.

This direction was intensified once Lenin died and Trotsky was first exiled and then assassinated. Stalin was firmly in control of international communism and he demonstrated that in Spain. Goldner traces the origins and practice of the Spanish Revolution of 1936–39, as well as its demise after the civil war between the Spanish Republicans and the military forces of Fascist General Francisco Franco. Goldner contends that in 1936:

the Spanish working class and parts of the peasantry in the Republican zones arrived at the closest approximation of a self-managed society sustained in different forms over two and a half years, ever achieved in history.

According to Goldner, the anarchists were a clear majority and had the support of both the industrial proletariat and the peasantry. In explaining the collapse and military defeat of the Republic, Goldner offers a critique, not only of Stalin’s communism and Trotskyism, but the theory and practice of the anarchists. He argues that:

The Spanish anarchists had made the revolution, beyond their wildest expectations, and did not know what to do with it.

Their reluctance in both theory and practice to seize power, which would have involved imposing a dictatorship, opened the door to Stalin’s gambit of attacking both anarchists and Trotskyists. And that weakened the Republic to such an extent that Franco’s forces were able to defeat it militarily.

In Bolivia, Goldner examines the revolution of 1952 when a formation called the Movimiento Nacional Revolucionarío (mnr) seized state power. A military junta controlled Bolivia at the time the mnr seized power. The mnr was a broad revolutionary movement that had been in existence since 1941. By 1952, they favored the nationalization of the mines and agricultural reform. Goldner goes into great detail about the formation of the mnr in relation to many other political forces that were active in Bolivia. He discusses specifically the fascist influences on the mnr and also a dominant false view of Marxism that was rejected as “Eurocentric.” Instead, the mnr favored a form of revolutionary society that would be some synthesis of European and Andean-Amazonian cultures. The main Marxist current active at this time was Trotskyist. Goldner spends a great deal of time looking at the various currents of Trotskyism that came to bear on its influence in Bolivia. Briefly, its leaders did not believe the time was ripe for socialist revolution in Bolivia. And they saw their role as constituting a “left wing” in a bourgeois-nationalist anti-imperialist movement that could push toward socialism by giving the mnr “critical support.” As a result the actual reforms instituted by the mnr government between 1952 and 1964 were limited to, as Goldner puts it, “corporatist nationalizations and half-baked agrarian reform.”

The theme that embraces all four case studies in this book—Russia, Turkey, Spain and Bolivia—was the need for theoretical clarity in revolutionary movements. Overthrow of a government will lead to missed opportunities if there is not a clear idea of where the movement is headed once state power is gained. The book is well documented so that a serious reader can follow Goldner’s exhaustive research to gain a deep understanding of four important historical revolutionary movements.

One aspect of each case that was not dealt with directly was that each revolutionary regime was threatened militarily by outside forces. After the Russian Revolution, there was an ongoing ferocious civil war aided and abetted by Britain and France. In Turkey, Kemal was opposed by the British who also suppressed communist forces. In Spain, it was Franco who attacked the Republic and Stalin who attacked the anarchists who controlled the Republican regions of Spain. And in Bolivia, there was constant military upheaval up to 1952 and the threat of us intervention. The question is whether strong theoretical clarity could have helped the regimes unite the people in opposition to these threats.

Goldner’s argument is grounded in his view that the wage-labor proletariat continues to be a “key force for a revolution against capital.” He also contends that the number of such proletarians in the world today is greater than ever. I agree and believe this book is an important read for today as we strive to meet the present crisis of capitalism and turn aside the reactionary trends that are on the ascendancy.

Comments

Wayne Price reviews Loren Goldner's "Revolution, Defeat, and Theoretical Underdevelopment: Russia, Turkey, Spain, Bolivia" (2017). Originally published on anarkismo.net and linked from issue 18 of Insurgent Notes.

NB: The book itself is available on Libcom here.

A review of a book by a libertarian Marxist sympathetic to anarchism who analyses four revolutions in the 20th century and discusses their lessons

This book brings together a set of analyses of popular struggles in a number of countries—as its subtitle indicates. It is written by a someone within “the libertarian or left communist milieu” of Marxism (43), although he expresses a friendly attitude toward anarchism. Overall it has a conclusion, a rejection of “a methodology repeated again and again whereby different variants of the far-left set themselves up as the cheering section and often minor adjuncts to ‘progressive’ movements and governments strictly committed to the restructuring (or creation) of a nation-state adequate to…world capitalism. This methodology involves imagining…a healthy ‘left’ wing of a bourgeois or nationalist or ‘progressive’ or Third World ‘anti-imperialist’ movement that can be ‘pushed to the left’ by ‘critical support’, opening the way for socialist revolution….Their role is to enlist some of the more radical elements in supporting or tolerating an alien project which sooner or later co-opts or, even worse, represses and sometimes annihilates them.” (225)

Goldner believes that rejecting this statist and capitalist “methodology” is necessary to re-arm the far-left if it is to overcome “the nearly four decades of quiescence, defeat and dispersion that followed the ebb of the world upsurge of 1968—77…the long post-1970s glaciation….” (1) “I nevertheless part ways with a swath of currently fashionable theories; I still see the wage-labor proletariat—the working class on a world scale—as the key force for a revolution against capital.” (2) He writes, “the key force,” not the “only force,” since he includes peasants and other oppressed as necessary parts of an international revolution.

This overall conception, from a (minority) trend in Marxism, is consistent with revolutionary class-struggle anarchism, as it developed from Michael Bakunin and Peter Kropotkin to the anarcho-syndicalists and anarcho-communists.

However, Goldner shows the limitations of his knowledge of anarchism by a number of errors. For example, he remarks that “the ideology of pan-Slavism [was] also advocated by their anarchist rival Bakunin….” (57) Actually Bakunin had been a pan-Slavist before he became an anarchist, not since. Goldner refers to “the early mutualist (Proudhon-inspired) phase of the Peruvian and Latin American workers’ movement (…superseded by the global impact of the Russian Revolution).” (171—2) But after an early period, most anarchist influence in the Latin American working class was anarcho-syndicalist (although there was still some interest in credit unions and coops, alongside unions). This is why the Sandinistas and other Central American revolutionaries (nationalist and Marxist) later adopted black and red as their colors.These had traditionally been the colors of the anarcho-syndicalist-influenced workers’ movement.

Lenin and the Russian Revolution

Goldner writes that revolutionary libertarian socialist currents, such as anarchism, syndicalism, council communism, and the IWW, “were effectively steamrollered by Bolshevism…and the ultimately disastrous international influence of the Russian Revolution….” (9) In this book, his criticism focuses on Lenin’s misunderstanding of the Russian peasants. Lenin overestimated the extent of the peasants’ production of commodities for sale on the market. He overestimated the extent to which capitalism had taken root among the peasants. He overestimated the decline of the peasants’ communal institutions (the “mir”). He overestimated the class stratification among the peasants. These misunderstandings led to an authoritarian, repressive, and exploitative relationship of the Soviet state to the peasants. They were a major factor in the split between the Bolsheviks (Communists) and the peasant-based Left Social Revolutionary Party. That in turn contributed to the formation of the single-party dictatorship. (See Sirianni 1982) “The Soviet Union emerged from the civil war in 1921 with the nucleus of a new ruling class in power….” (43)

Goldner also reviews the relations of the early Soviet Union with Turkey, then led by the nationalist, Kemal Attaturk. Goldner had previously believed, with the Trotskyists, that it was only under Stalin that international Communist parties were turned into agents of the Russian state and the world revolution subordinated to Russian national interests. But he found that the government of Lenin and Trotsky had sought close relations with the Turkish nationalists, even as the Turkish government was repressing and murdering Turkish communists. He quotes a memo from Trotsky at the time, saying that the main issue of revolutionary politics in the “East” was the need for Russia to make a deal with Britain.

However, Goldner defends Marx, and—more oddly—Lenin from anarchist charges of laying the basis for Stalinism. “I…reject the commonplace view one finds among anarchists who see nothing problematic to be explained in the emergence of Stalinist Russia.” (43) If he means that the Russian Revolution needs to be analyzed in detail, without assuming any inevitabilities, then I agree. And there are libertarian-democratic, proletarian, and humanistic aspects of Marx’s thought. But anarchists correctly rejected Marx’s program of a revolution in which the working class (or a party speaking for the working class) would seize power over a state and establish a state-owned, centralized, economy. The anarchists had predicted that this would lead to state capitalism and bureaucratic class rule. Whether this is “problematic,” it seems to have been justified by experience.

Goldner denies “that there exists a straight line, or much of any line, from Lenin’s 1902 pamphlet What Is To Be Done? to Stalin’s Russia.” (43) Maybe not; there is a democratic aspect of WITBD?, a call for the working class party to champion every democratic cause large or small (peasants, minority religions, censored writers, etc.), no matter how indirectly related to working class concerns. But Lenin treated support for democratic issues as instrumental, steps toward his party’s rule, rather than as basic values. Overall he had an authoritarian outlook. This can be demonstrated from much more evidence than just WITBD? (See Taber 1988.)

Anarchists and Trotskyists

Discussing the Spanish revolution/civil war of the ‘thirties, Goldner is “anything but unsympathetic to the Spanish anarchist movement.”(119) His views are similar to that of the council communists (libertarian Marxists) Karl Korsch and Paul Mattick. Then living in the U.S., they were supportive of the anarchist-syndicalists in the conflict (Pinta 2017). Goldner writes, “The Spanish working class and parts of the peasantry in the Republican [anti-fascist—WP] zones arrived at the closest approximation of a self-managed society, sustained in different forms over two and half years, ever achieved in history.” (118) He quotes Trotsky saying pretty much the same thing.

However, “Spain was the supreme historical test for anarchism, which it failed…,” adding, “in the same way that Russia was, to date, the supreme test of, at least, Leninism, if not of Marxism itself.” (118) Instead of organizing the workers and peasants in their democratic unions, factory councils, communes, and militia units, to replace the collapsed national and regional states—the mainstream anarcho-syndicalists joined the national Popular Front government and the Catalan regional government. “The Spanish anarchists had made the revolution, beyond their wildest expectations, and did not know what to do with it….Everything in the anarchists’ history militated against ‘taking power’ as ‘authoritarian’ [and] ‘centralist’….” (126-7)

Goldner does note that there were some anarchists who advocated a revolutionary program, not of joining the bourgeois government or of “taking state power,” but of organizing a democratic federation of workers, peasants, and militia organization to manage the economy and the war. In particular, there were the Friends of Durruti who “called for a new revolution.” (141) (For more on the Friends of Durruti , see Guillamon 1996.)

The main lesson Goldner draws from the anarchists in the Spanish Revolution is the need for radicals “to think more concretely about what to do in the immediate aftermath of a successful revolutionary takeover….[to devote] serious energy to outlining a concrete transition out of capitalism.” (149)

Discussing the Bolivian revolution of 1952, Goldner shows how the Trotskyists made the same sort of errors as the anarchists had in Spain. There was a revolutionary situation, where the Trotskyists for once had a large influence among the rebellious (and armed) working class. Instead of advocating independent power to the mass workers’ organizations, the Trotskyists gave support to radical (bourgeois) nationalists, claiming that they were really on the road to socialism (although, Goldner demonstrates, the nationalists had fascist influences in their formation). “The Trotskyist POR…ended up providing a far-left cover for the establishment of the new [bourgeois] state.” (214) Eventually, the Trotskyists were no longer useful to the nationalists and were repressed (the classical “squeezed lemon” process). The regime swung to the right. This was another illustration of the “methodology” of radicals tailing “progressive’ movements and governments strictly committed to the … nation-state [and] capitalism,” as I quoted in the first paragraph.

Anti-Imperialism? Anti-Capitalism? National Liberation?

I find Goldner’s opinions on “anti-imperialism” and national liberation to be unclear. He is correct in rejecting the left program which substitutes national struggles for class struggles, which ignores class (and other) conflicts within oppressed nations, and which spreads illusions about the “socialist” nature of nationalist and Stalinist rulers. But it is unclear whether he regards national oppression as a real issue for millions of workers and peasants. If we recognize this as a real concern, then libertarian socialists can be in solidarity with the people of oppressed nations, while opposing their nationalist would-be rulers. It becomes possible to advocate national liberation through social revolution and to propose a class struggle road to national freedom.

This would seem to be consistent with Goldner’s agreement with Lenin’s WITBD? strategy of revolutionary working class support for all democratic struggles, as well as Goldner’s expressed agreement with Trotsky’s theory of “permanent revolution.” He specifically condemns the Popular Front government in the Spanish civil war for “the failure of the Republic to offer independence or even autonomy to Spanish Morocco (…) which could have had the potential of undercutting Franco’s rearguard, his base of operations, and, in the Moroccan legionaries, an important source of his best troops. “ (129) That is, the liberal-socialist-Stalinist-anarchist coalition failed to adopt anti-imperialist policies (due to Spain’s imperialism and its attempted alliance with French and British imperialism).

This is a fascinating book, with detailed analyses of revolutionary turning points in world history. Loren Goldner’s discussion of these events and the issues which arise from them is important and useful for anti-authoritarian revolutionaries to consider.

References

Guillamon, Agustin (1996). The Friends of Durruti Group: 1937—1939. (Trans.: Paul Sharkey). San Francisco: AK Press.

Goldner, Loren (2017). Revolution, Defeat, and Theoretical Underdevelopment: Russia, Turkey, Spain, Bolivia. Chicago: Haymarket Books.

Pinta, Saku (2017). “Council Communist Perspectives on the Spanish Civil War and Revolution, 1936—1939.” In Libertarian Socialism; Politics in Black and Red. (Ed.: Alex Pritchard, Ruth Kinna, Saku Pinta, & David Berry.) Oakland CA: PM Press. Pp. 116—142.

Sirianni, Carmen (1982). Workers Control and Socialist Democracy: The Soviet Experience. London: Verso.

Taber, Ron (1988). A Look at Leninism. NY: Aspect Foundation.

*written for www.Anarkismo.net

Comments

S. Artesian reviews "Revolution, Defeat, and Theoretical Development: Russia, Turkey, Spain, Bolivia" by Loren Goldner. Originally published at Anti-Capital and then linked from Insurgent Notes issue 18, October 2018.

NB: The book itself is available on Libcom here.

Revolution, Defeat, and Theoretical Underdevelopment:

Russia, Turkey, Spain, Bolivia

Loren Goldner,

Haymarket Books, $28.

When Marx wrote that a specter was haunting Europe, he didn’t mean “national liberation,” anti-imperialism, the “tasks of economic development,” or the stages theory of history. He said what he meant and he said “communism,” requiring the overthrow of capitalism, its ruling class and its ruling relations of production, by the proletariat. Marx didn’t quite imagine the corollary proposition to his evocation of the specter of communist future– that the socialists, the “left,” the big and small C communists would be the ones scared to death of ghosts.

If all of the bourgeoisie’s economics, philosophy, sociology, and psychology of the past century amounts to the evasion of, and flight from Marx’s critique of capital (and it does), that’s only because all of the history of the last 100 years has been the flight from proletarian revolution through the substitution of national liberation, anti-imperialism, stages theory, popular fronts, for class struggle. Nothing persists in capitalism like obsolescence, planned or unplanned. Nothing has more currency, more staying power than the forms of rebellion that embody, embrace, and imitate the capitalist relations of production.

Loren Goldner, activist, author, and editor of Insurgent Notes, has produced four essays on the obstacles placed in the path to power by revolutionists themselves and Haymarket Books has compiled the essays under a single cover, and the single title Revolution, Defeat, and Theoretical Underdevelopment: Russia, Turkey, Spain, Bolivia.

The essays examine four ideologies, Leninism, anti-imperialism, anarchism and Troskyism through the real history of revolutionary struggle.

We begin with Russia. We are always beginning with Russia. The Russian Revolution is, after all, that location in time and space where the working class created and installed the original organs of its power to rule society, the soviets.

Russia was the crucible that yielded up the compounded upheaval of proletarian power and peasant war known as permanent revolution, itself the translation of the theory of uneven and combined development into the practical activity of class struggle.

There is no mistaking that each of Goldner’s studies– Russia before and after the revolution; Russia’s engagement with Turkish nationalism 1920-1925; the Spanish Civil War 1936-1939; the 1952 MNR revolution in Bolivia–is a “grapple” with uneven and combined development and with permanent revolution as the only viable path to the overthrow of capitalism.

The basics of uneven and combined development are well…basic. Capitalism does not develop uniformly, or by formula, across the globe. The ability of capital in any particular, local, environment to refashion society, to revolutionize the relations of production is circumscribed, and compromised, by the existing relations of property in which capital emerges, or is grafted on its “host.”

Marx wrote that a certain productivity of agriculture is required for the development of social organization. Capital, in its quest to fulfill its essential, and only essential task, the accumulation of more capital, requires more than just a certain level. It requires continuous advances in agricultural productivity, expelling the population from rural production, detaching that population from direct production of its own subsistence, and transforming agriculture from a subsistence activity where only a surplus product is available for exchange and into an activity where all product must be exchanged for a) the producer to subsist and b) surplus product to be replaced by surplus value extracted by and for the owner of the means of production.

To create those conditions of laboring, capital has to overthrow the pre-existing relations of property, of private property. That’s a risky business for capital as its private property is enmeshed in the general networks of credit, debt, commerce, and trade with those pre-existing forms. That’s a risky business given the sanctity of private property to the bourgeoisie in general.

Where “local” capital finds itself surrounded, stifled even, by pre-existing relations of land and landed labor, capitalism as an international system is able to insert “islands”– “zones” of industrial activity where the condition of labor is that of wage-labor, essentially the same as the condition of labor in the most advanced countries.

The result of this uneven and combined development is that agriculture does not achieve a level of productivity able to sustain a “reciprocity” between city and countryside; sufficient to sustain the accumulation of capital; and that advanced capitalist economies dominate these areas.

Just as capital is overwhelmed by the weight of all pre-existing relations bearing down on it, the capitalist class cannot make, much less lead, a revolution.

This also means that while the working class can seize power during a social upheaval, that seizure can only be sustained through the transformation of agricultural production beyond the conditions of capitalist accumulation, beyond the condition of labor as wage-labor. For the proletarian revolution to be successful, the transformation of agriculture cannot be the imitation of or analogy to capitalism, i.e “state” as the imitation or analogy to “corporate” units.

So Goldner begins with the “agricultural question” and the Russian revolution. He explores Lenin’s misrepresentation of production in the countryside as being “capitalist” not only in tendency but in fact. No such capitalist dominance had occurred or was even emerging in Russian agriculture. The large landed estate, the landlord-peasant relation, as opposed to landowner-free farmer relation continued to dominate, and the Russian peasant commune, the mir or obschina, remained at the heart (and soul) of the peasant social organization.

While the Czar’s bureaucracy saw the mir as a tax collecting body, the mir was an organization designed to ensure an equitable distribution of land, and tools, among its members. This equitable “rationing” made the commune deeply resistant to commercial penetration

To argue that capitalism was becoming dominant in the Russian countryside required both a distortion of the empirical data and an ideological commitment to “developmentalist” economics, which is itself nothing but stages theory all dressed up in the clothing of “destiny.” It was an argument that, when turned into policy, was made at the expense of historical materialism and ultimately, social revolution.

After the civil war in Russia, the Bolsheviks adopted programs designed to appeal to the so-called “economic rationality”– the “individual commercial interest”– of the rural producer as the mechanism for developing agriculture and transferring surplus from the countryside to the city, from agriculture to industry. Goldner demonstrates that the commune undermined the appeal to such “rational self-interest.” The policies did, however, make the Bolsheviks advocates, even if unwilling or unwitting ones, for an economic differentiation among the peasantry, and thus made them, the Communists, substitutes for a bourgeoisie.

In discussing the NEP, Goldner correctly points out that the Bolsheviks intended it to “guide capitalism” in an effort to revive agriculture and industry. And he’s right when he says that the NEP was not a “restoration of capitalism,” but he’s wrong when he says “because capitalism had never been abolished in the first place.” The NEP was not a restoration of capitalism because capitalism had never been established in the countryside in the first place.

The peasant communes were under attack, prior to the revolution, certainly, as the “enlightened Czarists” (an oxymoron to beat all other oxymorons) sought a capitalist transformation of agriculture, but the communes survived, and remained as they had always been– subsistence plus marginal surplus units of production. The surplus was “marginal” in the sense that the surplus was not the organizing principle of production. The surplus product was made exchangeable, unlike the condition of capitalist agriculture where all product must be produced for exchange in order to realize the surplus value embedded in the whole.

The Bolshevik predicament was that the revolution could not adequately enhance agricultural productivity because agricultural productivity was already too low. The escape from this trick-bag, of course, was only possible through the expansion of the social revolution into the advanced countries, and this in turn required the ability and willingness to continue the pursuit of revolution in the less-developed countries.

Which gets us to Goldner’s second essay “Socialism in One Country Before Stalin.” This essay deals with the ebbs and flows of the Bolsheviks’ accommodation to post-WW1 Turkish nationalism, and in particular the “romance” with Kemalist Turkey under the guise of support for “national liberation.”

The raising of post-Ottoman Turkey as struggle for national liberation endorsed by the Bolsheviks (and the Third International) was a pragmatic decision by the Bolsheviks as no issue of national liberation existed. The conflict was an inter-, and intra-,capitalist, competition. The Bolsheviks engaged in their maneuvering in order to secure their borders with Asia against the British even if, or precisely because, revolution appeared imminent on those borders.

Those maneuvers involved the sacrifice, literally, of Turkish communist militants to the Kemal regime; the transfer of gold and weapons to Kemal after that sacrifice; and all of this in the period 1921-1925, before the policy of socialism in one country was announced; before the sacrifice of the Chinese Revolution on the altar of national liberation.

This might help us understand how of much of the “ebb” of the revolutionary wave was the result of the Bolsheviks’ (and the Third International’s) own actions. The answer? “A lot.”

National liberation has not always been presented as a mechanism primarily for class collaboration with a “national” “patriotic” or simply “petty” bourgeoisie but it has always been rationalized as a precursor, a stage necessarily prior to a proletarian revolution, akin to a “bourgeois democratic revolution” or even the unworkable “democratic dictatorship of the proletariat and the peasantry.” What the Russian Revolution exploded in its triumph, the stages theory, the Bolsheviks brought back through the trap door of national liberation.

From precursor, national liberation becomes the substitute for class struggle; and from substitute it moves to become the opponent of class struggle. Thanks to Goldner’s essay we can answer another question: When does a workers’ state stop being a workers’ state? When it establishes policies and undertakes actions separate, apart, distinct from, and in opposition to the advance of proletarian revolution.

Goldner’s remaining two essays in the volume, “The Spanish Revolution, Past and Future,” and “Anti-Capitalism or Anti-Imperialism…” (concerning the MNR and Bolivia), deal with the legacy of two revolutions where defeat was snatched from the jaws of victory.

In both Spain and Bolivia, the revolutionary struggle, populated by workers and rural poor is again sacrificed to the “stages” of history, the “economic tasks of development,” the ideology of substitutionism that becomes the practice of opposition to social revolution.

In the case of Spain, the anarchists presented overwhelming, but atomized class power. Failing to centralize that power, to exercise that power as its class dictatorship, the anarchist organizations allowed the popular front to organize counter that class, counter that proletarian revolution, as if the struggle were one for a bourgeois democracy.

Finally, in the examination of the MNR and Bolivia, Goldner engages in an exhaustive examination of the fascist, near-fascist, populist, and corporate ideologies on the formation of a “national movement.” Goldner is fascinated by the impact of German Romantic Populism, and the German military, on the formation of movements among intellectuals and the military officer in the countries of Latin America. If I were a glib person, I might say comrade Goldner is a bit too concerned with the ideological formulations of intellectuals.

I’m not. I’d say that the development of capitalism in Bolivia was so constrained by internal factors like the Spanish mita, the encomienda, the hacienda, and by the market power of the advanced capitalist countries that intellectuals, administrators, professionals, students, military officers were compressed between the rock and the hard place, that space between the rock and the hard place being a void. Under those circumstances, ideologies of the state, as an entity somehow raised above class differentiation, and representing the “people” as the volk provided the intellectuals with a fantasy of accumulation in the midst of the most impoverished of realities.

Beyond that, the story of the Bolivian Revolution and the MNR is the story of the armed intervention of the workers in the coup initiated by the MNR against the mine-owners’ government; the conversion of a coup into class struggle; the frittering away of that revolution by the Trotskyist POR which, terrified by the specter that once haunted Europe, constituted itself as an adjunct to the “left wing” of the MNR. Goldner is correct when he writes that “to ‘blame’ the POR for ‘betraying’ the Bolivian Revolution is to fall into the idealist trap of saying ‘they had the wrong’ ideas’ instead of explaining why they had the ideas they did.” The explanation is not, however, that those ideas were then— that those ideas were the legacy of a capitalism not sufficiently, nor globally, dominant. In fact, those ‘ideas’ were precisely a recoil, a flinching, in the face of a capitalism that was indeed globally dominant, had itself overgrown the notions of definitive stages– it was and is, and will always be until its overthrow, a capitalism where the limitations are not simply limitations upon capital, but limitations of capital itself.

February 27, 2018

From: https://anticapital0.wordpress.com/impermanent-revolution/

Comments

S. Artesian wrote: When Marx wrote that a specter was haunting Europe, he didn’t mean “national liberation,” anti-imperialism, the “tasks of economic development,” or the stages theory of history. He said what he meant and he said “communism,”...

The Manifesto states that the ghost of communism haunts Europe. In other words, it is communism's spectre, not communism itself. Therefore, it is precisely the type of things that Artesian lists that Marx is referring to in the preamble of the Manifesto. National liberation, establishment of the nation, is one means of subverting communism, of subverting our class struggle into its opposite, its ghost, its death.

When the day labourers of Gaza rose up against the Israeli Defence Force in 1987 against the daily torture and humiliations of working in the State of Israel, for Israeli capital, the proletariat asserted communism. In defence of its own capital interests the Palestinian mercantile class attempted to portray the intifada as a national liberation struggle. It attempted and attempts to create a mirage.

Admin: eugenicist Covid-denial removed. User had been repeatedly warned against posting Covid-denial. Now banned.

So stupid "repeated covid-denial" is a banning offence - but the far more topical repeated posting of links to active fascist sites is not?? https://libcom.org/article/untold-experiment-national-syndicalism-when-fascism-was-decay-socialism

Loren Goldner reviews "Pictures of a Gone City: Tech and the Dark Side of Prosperity in the San Francisco Bay Area" by Richard A. Walker for Insurgent Notes #18, October 2018.

…Silicon Valley fever is a disease of a social body infected with the overheated pursuit of riches and expansion.

—Richard Walker

Richard Walker says in his exceptional book Pictures of a Gone City that someone who grew up in the San Francisco Bay Area in the decades following World War II would not recognize the place today. As one such person, who fled the gentrification of the area decades ago, I can only agree. Walker is an emeritus professor of geography at uc Berkeley and seems to have made the social, political demographic and environmental history of the Bay Area his life’s work. He also uses a Marxist framework of analysis, though is a bit weak on real class struggles and strategies looking forward. He also seems to treat some official state and local institutions with more respect than I would, presenting them as partial ramparts capable of slowing or correcting the negative trends at work, at least under pressure “from below.” He is no fan of the Democratic Party, but also no mass strike theorist, and this blind spot is one main flaw of the book. But I’ll take Walker and this flaw, along with all his rich layers of analysis, rather than neither. (He takes his title from Lawrence Ferlinghetti’s poem “Pictures of the Gone World” which opens the book.)

The Bay Area after 1945 was a unique “scene” in the United States, something of which I only became fully aware when I left it. What happened (or at least accelerated) there after the mid-1970s was the superimposition of a fictitious, artificial, culturally and historically ignorant, self-satisfied and narcissistic tissue over most aspects of the previously lived reality, as if those driving the process were using Guy Debord’s Society of the Spectacle as a counter-insurgency manual. Not to jump ahead, but the fact that almost no ordinary black people any longer live in San Francisco, says just about everything.

Based on Walker’s title, I for one opened the book expecting more of a portrait of postwar Bay Area Bohemia and its general demise. The San Francisco/Berkeley core of the region was something of a refuge for 1930s and 1940s leftists keeping their heads down during the worst (late 1940s/early 1950s) years of McCarthyism, for which payback came in the 1960 riots against the notorious huac (House Un-American Activities Committee) hearings in San Francisco, which effectively killed it off. The working-class Italian restaurants in San Francisco’s North Beach, frequented by radical longshoremen and poets alike, the cafés, the jazz clubs, the (black) Fillmore district, night clubs such as the Hungry I or the 1960s satirical review The Committee, art cinema houses, Pacifica Radio, bookstores such as City Lights (founded by Ferlinghetti in 1951) or Cody’s in Berkeley, the affordable rental housing in the pre-hippie Haight-Ashbury and elsewhere in pre-yuppie Victorians, were all part of a “scene” that tilted left, building on Kenneth Rexroth’s post-1945 circle of poets and anarchists. Beat poets and writers such as Allen Ginsburg and Jack Kerouac later animated this scene, in which writers and artists and musicians and political activists could live cheaply and pursue their work. It was a scene of a time and a place, about whose broader social and economic limits those who breathed its heady atmosphere did not think too much, until gentrification wiped it out or neutered it, leaving behind little except icons (as with City Lights bookstore or the Cafe Trieste at Vallejo and Grant Streets) of a bygone era. It was the exact opposite of rank apologist Richard Florida’s “creative classes” of web site designers and the startup capitalists who displaced it.

Walker is aware of this demise, and critiques it, but not quite as forcefully as the money-driven forces that buried Bay Area Bohemia and working-class radicalism deserve.

Meanwhile, at the south end of the bay, those money-driven forces, associated with Silicon Valley high tech (or simply “tech”) were preparing to turn parts of the region into one of the wealthiest areas in the world, one which had little or no place for the left Bohemian and labor scene sketched above. Much has been written about the role of the hippie counter-culture in the rise of Silicon Valley, embodied in its best-known icon Steve Jobs of Apple, who traveled barefoot in a saffron robe in India before becoming an entrepreneur. So be it. Walker argues that this counter-cultural background of Silicon Valley tech partially explains its triumph over Boston’s more staid Route 128, being more inclined to “think outside the box.”

This “high tech” scene had origins in the South Bay region (Palo Alto and environs) as early as the 1940s, but truly took center stage in the 1970s, ultimately giving rise to most of “tech’s” contemporary “fangs” (Facebook, Amazon, Netflix, Google and Snapchat). To the high tech “campuses” of the South Bay, however, outfitted with everything from exercise rooms to free gourmet food to childcare available 24/7, Walker counterposes the three or more million proletarians, increasingly Latino and Asian, who do the unglamorous scut work that keeps the region moving, and who are immune to the hype surrounding Silicon Valley since, as he puts it, “so little of the manna from tech heaven fell their way.” Nor does he neglect to mention the extra-long hours that tech workers themselves put in, in between their extra-long commutes. (Some of them merely sleep under their desks.)

Walker gives a “thick description” of the dot.com scene of the 1990s, notorious for such short-lived meteors as pets.com, or others, described by older, less sanguine figures such as banker and onetime Federal Reserve chair Paul Volcker, marveling at multi-million dollar ipos (Initial Public Offerings) of startups that had never turned a profit, all of it culminating in the dot.com meltdown of 2000. The 1990s were the era of the “New Economy,” presumably one which had transcended the grey-on-grey laws of capitalist accumulation, until it hadn’t. This was similarly the era of the Bill Clinton mini-boom of the late 1990s, the only uptick to date for workers’ wages in a (briefly) tight labor market since the long stagnation began in the early 1970s. It also saw the ephemeral beginnings of a pay down of the Federal deficit, with “surpluses as far as the eye could see.” It seemed too good to be true, and it was. In a new expansion after 2000, hundreds of millions were again “pouring in to back up start-up Wag Labs, whose app connects dogs owners and dog walkers.” “In the end,” Walker writes, “the ideology of plucky start-ups ran into the hard realities of commerce and capital…”

Given the intrusion of the big tech firms into every aspect of life, as has, for example, been coming to light in Facebook’s Cambridge Analytica scandal, it is hardly surprising that disillusionment “with the lords of the Tech World…has been exploding in the last few years, taking the shine off the image of once shining knights of liberty, equality and information for all.” Walker demystifies the “much ballyhooed entrepreneurs and start-ups of today” who in reality draw on a century of earlier electronics technology development. They cannot be reduced to the “discoveries of modern science and men in white coats.” He does not forget the “cold bath of governmental assistance”: World War II purchases of radar and sonar tubes “made” by Hewlett Packard and Varian; the Department of Defense dominated digital computing right through the 1960s. Not to be forgotten was the National Science Foundation, funding research at Stanford and Berkeley: “The original internet was a DoD project…”

The theory of the creative class, writes Walker, “leaves out the majority of workers in the industry.”

The tech industry may be the pinnacle of modern industrial sophistication, innovation, and profitability, but it still rests on a mountain of ordinary labor…the tech industry could not function without a host of people doing manual, routine and unglamorous jobs. Counting such workers is made more difficult still by widespread subcontracting, primarily of people of color, Filipino, Vietnamese and Latino. This goes together with the failure to mention all the labor done in and for the tech industry overseas. The global reach of the Bay Area’s tech giants is motivated by one thing above all: access to cheap labor.

These include Foxconn’s workers making iPhones in Shenzhen, where a wave of high-rise suicide leaps in 2010 led the company to “install nets outside dormitory windows.” Contrary to the dominant ideology touting “risk takers,” writes Walker, “the success of the region rests on broader foundations, which are too often missing from the story of Silicon Valley fever: industrial clustering and urban agglomeration, the base technology of electronics nurtured in the region, and the labor of thousands of skilled workers and millions of others.” The fangs and the tech elite also engage in massive tax avoidance though the usual venues of “the Bahamas, Luxembourg and the Channel Islands.”

For all this wealth, Bay Area tech has been slammed by two major stock market routs, in 2000 and then in 2008. The region lost “half a million jobs, and only crept back to the employment level of 1999 by the end of 2015.” These meltdowns “bankrupted thousands of homeowners”; two million state employees lost their jobs and unemployment hit 12 percent. Commenting on the post-2009 expansion still underway when his book went to press, Walker writes:

The mainstream press rarely delves into the cumulative consequences of recessions, other than quoting unemployment figures. Reports on growing homelessness, poor health, and rising divorce rates are rarely connected to the hidden costs of economic recession crashing down on the heads of ordinary folks. But when the current economic wave breaks on the reef of capitalist excess, a huge amount of wreckage will be revealed on the shores of the Pacific Coast’s star performer.

In the Bay Area work force, the area “may be a high average wage region, but millions of people still go home with middling to lousy paychecks… People in humble jobs, such as custodians, security guards, and nursing aides, are not feeling the buzz.” As for comparative national income differentials, “the four counties of the West Bay come out much worse, ranking somewhere on a par with Guatemala, putting the heartland of High Tech neck and neck with a nation of latifundia…Low-wage work employs well over a third of the labor force, or around 1.3 million people, which translates into 3–4 million in those working families. This is only slightly better than the proportion of low-wage work in California and the nation…the well-off elite and salaried workers depend every day on the labor of millions of ordinary workers who are overwhelmingly not white and not male.” Inequality, Walker points out, “literally makes people sick and unhappy… Not surprisingly, among rich nations, the United States and Britain—where inequality is greatest—come off as the worst in measure after measure, from longevity to obesity, mental health to physical ailments.” The two countries also have “the weakest social safety nets and the harshest attitudes toward personal failure… The glow of the Bay Area’s success is deeply tarnished by the tragic residue of thousands of homeless people on street corners, living out of cars, and camping under freeways.” One troglodyte member of the tech elite did not mince words:

Every day, on my way to and from work, I see people sprawled across the sidewalk, tent cities, human feces and the faces of addiction. The city is becoming a shantytown… The wealthy working people have earned their right to live in the city. They went out, got an education, work hard, and earned it… I shouldn’t have to see the pain, struggle and despair of homeless people on my way to work every day.

Cities such as San Jose, San Francisco and Oakland have ramped up the war on the homeless, ejecting (among other things) tent encampments. A “society that allows so many people to fall into public destitution in the face of abundance is a moral failure of the first order.”

“A truly shocking aspect of work in the bay metropolis is how many lousy jobs there are in such a high-flying, sophisticated economy.” Walker identifies these in retail, hotels, cleaning services, food preparation and domestic services. When high costs price such workers out of housing, “a chorus of howls about their absence goes up from employers, politicians, and upper-class households.”

“The postwar regime of stable, full-time and lifelong employment is a thing of the past.” The new normal is flexible or contingent employment, subcontracting, temp work and self-employed “consultants.” These latter make up between one-quarter and one-third of all jobs, culminating in the “Gig Economy.” The latter is “the antithesis of collective responsibility and class solidarity.”

Walker is presenting an ongoing process of class formation: “A new American working class is coming into being and it is heavily weighted with people of color…something unprecedented is happening here in the Bay Area and across the state… The working population has been transformed from majority White to majority Brown, with a touch of other colors.” Day laborers are undocumented immigrants “from native Indio groups in Southern Mexico and Guatemala who do not always speak Spanish, let alone English.” They stand on street corners and work in “heavy landscaping, debris clearing, crawling under houses, and other nasty jobs.” One quarter of all Californians are foreign born, coming from all over the world. This “overlap between immigrant rights and labor organizing” has made California a national vanguard while “the rest of the United States is still trying to get its collective head around mass immigration.” Nevertheless, Bill Clinton, George W. Bush, Barack Obama, and now Donald Trump have deported millions, and the current amplified hysteria around “illegal and criminal” immigrants is feeding the raids of ice (Immigration and Customs Enforcement) and Homeland Security around the country.

There is much more to Walker’s book, far more than can be included in a (relatively) short review. I urge Bay Area (and other) militant comrades to bracket Walker’s shortcomings as a Marxist and to use this book for more incisive interventions of their own. The hard left would do well to produce its own, improved version of such an exposé.

August 2018

Comments

From Insurgent Notes #18, October 2018.

I haven’t written much lately…partly for personal reasons. I’m old and my head and hands find it increasingly difficult to combine chain-sawing and wood splitting with thinking about politics and manipulating a keyboard. However there are some more general reasons for my silence that others may share to some extent. We’re at a political moment that is disorienting on many levels. Experiences that should strengthen us do the opposite. Opportunities and potentials explode on the scene only to disintegrate almost as quickly as they arise…generally leading to increased demoralization rather than providing the foundation for new initiatives. And such initiatives, to the extent they attempt to develop functional and resilient structures on a left mass or left cadre basis, start too small and tend to quickly get smaller—fragmenting and imploding over dismayingly similar conflicts—typically routine dilemmas and disruptions that we should have learned how to deal with, but quite apparently haven’t. And this all happens when a number of features of objective conditions appear to favor the emergence of a generalized opposition to established power.

It’s not much of a comfort, but these problems aren’t unique to our sector of the left, to this part of the world, or to this period of history. This is where I think it might be helpful to remember Gramsci’s oft-cited words about the characteristics of a period where the old is dying but the new is not ready to be born:

The crisis consists precisely in the fact that the old is dying but the new cannot be born; in this interregnum a great variety of morbid symptoms appear.1

Not that that such an observation provides much comfort either!

For some decades we have lived through a period where capital’s global triumph also marked the beginning of its secular crisis. The ruling class’s chronic and expanding difficulties in maintaining capital’s productivity and profitability interact with growing fault lines in its political legitimacy and effective power…shredding the pretensions that capitalism marks the end of history that were widespread not so long ago. Our dilemma…or one of them…is that this underlying crisis doesn’t develop uniformly. It passes through rough cycles and we are at a relatively bad point in the latest of these where capital is achieving some adaptive successes. One of the benefits of being quite old is that I have lived through a number of such cycles, including the end days of the one that initiated in an earlier period of capitalism—the depression of the ’30s. Hopefully I’ve maintained sufficient political awareness to provide some context and perspective for the current left malaise.

If we take 1935, 1968, and 2009 as points of significant breaks in capital’s evolutionary stability—a rough periodization that I know doesn’t apply uniformly across the global terrain, although it works for most of the capitalist core—they start from sharp breaks with political routine characterized by a flowering of radical possibility. Elements of creative spontaneous struggle appear everywhere and look to be inexorable. What previously seemed utopian or even impossible becomes a basis for live action on a mass level; mass action that includes widespread epistemological breaks that appear to foreshadow the emergence of a mass revolutionary subjectivity. Experience indicates that every cycle of crisis and the explosion of political possibility that accompanies it lead to an adaptive response of capital on both the level of profit (the economic) and that of power (the state). For examples; the emerging conflict between nationalism and globalism—too simple a dichotomy I know—is both an index of crisis and a path towards a possible capitalist recovery. The juxtaposition of an autonomous fascism with new forms of globalized social democracy should be understood in the same vein in my opinion.

Failures to adequately understand these circumstances promote some distinct left responses and an assortment of illusions. One such rests on the expectations that the dramatic changes of the moment of crisis are linear and incremental—and will define the political context for an extended period—if not permanently. A possible implication of this view—familiar in our tendency—is to limit our role to facilitating the mass process and, above all, to avoid becoming an obstacle to them—even as such processes begin to lose their oppositional potential. An alternative approach of others on the left sees the transformed political scene as the long-delayed fruits and validation of past labor and takes steps to implement a claim on organizational leadership. In the process the “vanguard’s” politics become either irrelevant or more frequently, indistinguishable from those of overt reformists. The best that can be said about such positions is that they fail to recognize major characteristics of these cycles of struggle.

Unfortunately, moments of general insurgency tend to be short-lived and, like the initial burst of popping popcorn, they are followed by increasingly sporadic and incomplete explosions of the lagging kernels. This process creates some forks in the road for radicals where diminishing grouplets search for better outcomes from fewer struggle opportunities while attempting to survive as groups and individuals. This frequently contains a tinge of desperation and results in a moralistic exhortative approach to political work that is not sustainable with normal-assed people. At the same time an increasing fraction of the momentarily radicalized lapse into cynicism or accommodations to some variant of reformist politics—which itself is often only a stepping stone to cynicism and passivity. As the reality of a mass epistemological break with established politics recedes into nostalgic memories and overly hopeful estimates of current forces, we quickly find ourselves in a period which the jaded among us call a lull—sometimes not very helpfully. I think it’s useful to think about what can and should be done in such a “lull”—particularly if it can be kept in mind that no lulls will be permanent.

I want to raise two related responsibilities and opportunities: first it’s important to use the opportunity to collectively think about our circumstances; and second this collective thinking should never lose focus on the potential for the radically changed circumstances which will certainly materialize. Sooner, I think, rather than later. Just a few words on both points!

I emphasize the importance of combining attempts to develop a radical collective will with an organized approach to developing capacities to think collectively—involving exchanges of estimates and hypotheses between positions that don’t agree and don’t necessarily look to reach agreement; exchanges designed to expand critical participation in the discussion rather than gaining adherents to some version of the truth; exchanges that aren’t subordinated to organizational empire-building or distorted by assumptions that the relevant questions are self-evident and that adequate answers are close at hand.

My initial assumption is that the general instability of the situation—the “flailing and churning” within capitalist power and the diverse questioning of its legitimacy and permanence—will turn out to be decisive. However, that is certainly open to question and challenge and I recognize that history is not clearly on my side on the issue. While this assumption is in some tension with the need for clear and critical political discussion that is not weighed down with a lot of preconceptions, I think it is vitally important to focus on the circumstances, objective and subjective, that raise possibilities for breaks, “events,” qualitative changes in context, and to propose approaches to deal with the possibilities that these will create.

- 1“Wave of Materialism” and “Crisis of Authority,” Selections from the Prison Notebooks. International Publishers, 1980: p. 276.

Comments

“Racial dissidents have lost the ability to organize openly”: Alt-rightists on Trump, ice, and what is to be done. Matthew Lyons in Insurgent Notes #18, October 2018.

The alt-right, or alternative right, represents the most recent major upsurge of far right politics in the United States. Blending white nationalism, misogyny, and aggressive social media activism, alt-rightists helped put Donald Trump in the White House and proclaimed themselves the vanguard of the Trump coalition. Although they never believed Trump shared their politics, most of them hoped he would buy time and political space with which they could further their own goal of a white ethno-state.1

In 2017 alt-rightists made a push to broaden their scope and impact by linking up with more traditional neonazi forces and expanding their activism from the internet to physical rallies and street violence. But since the brutal August 2017 “Unite the Right” rally in Charlottesville, at which one antifascist counterprotester was killed, the alt-right has suffered a series of setbacks. Several major alt-right websites have been forced to find new platforms or shut down entirely, infighting and personal conflicts have weakened the movement, and antifascist mobilizations have blocked their mobilizing drive. In addition, as Trump embraced conventional conservative positions and priorities on many issues (from cutting corporate taxes to bombing Syria) and pushed out several of his more “America First”–oriented advisors (such as Mike Flynn and Steve Bannon), many alt-rightists became increasingly alienated from Trump. Some declared that he has been bought off or blackmailed by Jewish elites, while others held out hope that his populist-nationalist tendencies could still win out.2

Recent actions by Trump (launching trade wars against China and the eu, criticizing nato allies, and holding friendly meetings with Kim Jong Un and Vladimir Putin) have reintensified his conflict with the conservative establishment, while the crackdown on undocumented immigrants has made his administration look more nativist and authoritarian than ever. How have alt-rightists responded to these developments? In this article I’ll explore alt-rightists’ current outlook, focusing on three issues: attitudes toward Trump, responses to the border crackdown and law enforcement more broadly, and political strategy in a time of weakness.

In broad terms, the alt-right’s views on Trump fall in between those of the Patriot movement (which appears to be squarely behind him) and neonazi groups unaffiliated with the alt-right (which are generally hostile).3 Alt-rightists like the steps Trump has taken to restrict immigration and punish immigrants, but wish he would go a lot further. Applauding the Supreme Court’s decision upholding Trump’s third ban on travel from majority Muslim countries, Hubert Collins of American Renaissance called on him to ban immigration from El Salvador, Honduras, and Jamaica, claiming that “such a ban would save lives and slow the displacement of white Americans.”4 Identity Evropa (arguably the most successful effort to move alt-right politics from the internet to real-world organizing) simply calls on the president and Congress to end all immigration to the United States.5

Writers at Occidental Dissent have been generally scathing in their assessment of Trump’s administration. Marcus Cicero, for example, wrote, “We were promised isolation and got further Middle Eastern conflict, we were promised a protectionist economy and got watered down free trade, we were promised sealed borders and a wall and got hordes of feral Mestizos, and we were promised realpolitik and got slavish devotion to Israel.”6 Brad Griffin, Occidental Dissent’s founder, who blogs under the name “Hunter Wallace,” agreed with Mitt Romney (an establishment conservative loathed by alt-rightists) that Trump’s actions in his first year as president were very similar to what Romney himself would have done.7 But even Griffin and Cicero have praised a few of Trump’s actions, such as ending Obama-era affirmative action policies and holding peace talks with North Korea’s Kim.8

In contrast, Andrew Anglin of the Daily Stormer has tended to downplay his criticisms of Trump. “I know his faults. I know there are Jews in his office. I know he bombed Syria. Twice…. But when I watch these rallies, my heart is saying ‘there’s the leader of my people, he is fighting to protect us.’ ” And further: “what he is doing, at least with the rallies and the tone, is Fascist in spirit. He is authoritarian, nationalist, and anti-liberal. The racial element isn’t there yet explicitly, but it certainly is there implicitly.”9

As a rule, alt-rightists have been strongly supportive of the Trump administration’s border crackdown and “zero tolerance” policy toward undocumented immigrants and asylum seekers. Hubert Collins declared that Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ice) protects Americans against foreign criminals and deserves full support.10 Many alt-rightists, like Patriot movement activists and other Trump supporters, have deflected criticisms of ice’s family separation policy by turning pro-family arguments against ice’s critics. American Renaissance wrote of “illegals” “using children as human shields” and dismissed criticisms Trump’s border policy as “hysteria” and “liberal viciousness.”11 Huntley Haverstock of Counter-Currents, drawing on the manosphere-type misogyny that has become standard across the alt-right, declared that newsmedia sound clips of immigrant children crying for their parents represented “emotional abuse against women”—more specifically, an “attempt to hijack women’s hindbrains and override all possibility of rational thought” because “the sound of crying has such a powerful mammalian impact on women that it can literally cause them to lactate.” Haverstock called this supposed physiological reaction healthy and positive in the right context, but in a political context it was “an argument against giving women the vote.”12

However, alt-right discussions regarding ice have gone well beyond these sort of reflexive attacks on immigrant rights politics. Anglin proclaimed that ice is Trump’s “Praetorian Guard,” the only non-corrupt federal enforcement agency, which the president will use to implement martial law and impose a dictatorship.13 As with many of Anglin’s statements, it’s hard to know to what extent he was being serious and to what extent he was just mixing wishful thinking with provocation for its own sake. In contrast, VDare columnist Federale has long argued that ice is a sham immigration enforcement agency that actually prefers to target non-immigrants.14 R. Houck of Counter-Currents went much further, declaring that all police and federal law enforcement agencies are part of a “hostile occupation force” and “are used first and foremost to protect Jewish interests.” Reversing the arguments of Black Lives Matter activists, Houck claimed that police actually are more likely to use deadly force against whites than blacks, and that “all bias in policing is in fact against the white race.”15 These assertions, aimed to counteract many rightists’ pro-police sentiments, highlight the difference between system-loyal and oppositional versions of right-wing politics.

The alt-right’s setbacks of the past year and misgivings about Trump have spurred some members to take a sober look at the movement’s strategic prospects. Many Republicans are predicting an electoral triumph this November and see the recent victory of democratic socialist Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez in a New York congressional primary as proof that the Democratic Party is out of touch with most voters. American Renaissance’s Gregory Hood disagreed, and, like other alt-rightists, his political hostility extended not just to liberals and leftists, but also to conservatives:

Despite (or because of) media coverage, racial dissidents have lost the ability to organize openly, while the socialist Left has gained in strength…. The established conservative movement has largely cheered this process. The Trump victory did not lead to a more welcoming environment for identitarians within the gop but increased scrutiny and barriers.

In contrast, the dsa [Democratic Socialists of America] has the most powerful combination in politics—revolutionary cachet combined with support from the power structure.

* * *

The Republican message of “economic growth” is uninspiring compared to the Democrats’ racial socialism, especially when corporate America and economic elites are more favorably disposed towards multiculturalism than they are to Trump-style nationalism. Unless President Trump can truly transform the gop into the “Workers Party” as he promised during the campaign, it’s unlikely his coalition will last.

In this climate, Hood urged white nationalists “not to daydream about Donald Trump’s ‘Red Tide,’ but to build institutions to ensure our people’s survival in the years when whites will be living under an occupation government.”16

Writing from a similar perspective, James Lawrence of Counter-Currents dismissed hopes that large masses of whites will embrace white nationalism and rise up against the established power structure as “alt-right victory fantasies.” He urged alt-rightists to learn from how twentieth-century fascist movements achieved power. Using Robert O. Paxton’s analysis in The Anatomy of Fascism (which is also a favorite among many critics of the right), Lawrence drew a number of lessons, including these:

- “The fascist experience…illustrates the importance, yet also the limitations, of metapolitical action,” i.e., a “process of mental preparation going back decades, in which the failings of liberalism and democracy were exposed and the decline of Western civilization was discussed. This smoothed the way for the creation of fascist movements in the wake of the Great War, but did not guarantee their success.”

- “successful fascist movements must cultivate not only the masses but also the vested interests of society. They must be encouraged, or at least tolerated, by an established ruling elite focused on the greater threat from leftist revolution.”

- fascism “cannot be recreated in the present era.… The modern avatar of leftist revolution is not a military threat from beyond the frontier [such as the ussr in the 1920s], but a political enemy ensconced in every official institution, and it is now the ‘antifa’ and ‘sjws’ who enjoy judicial leniency and elite patronage.”

- “Of the three stages of fascist pathbreaking, the only one available to us right now is metapolitics…. This can never induce the masses to rise up and replace that oligarchy of their own accord, but it can ensure that they become convinced of its illegitimacy and unwilling to react strongly against threats to its power. That is the first step from which all others must follow.”17

Lawrence and Hood’s pessimistic but reasoned call for alt-rightists to prepare for many years of base-building stands in stark contrast to Anglin’s glib optimism, in which Donald Trump serves as a deus ex machina for the movement’s own failings. These are two sides of the same movement. Today the alt-right is significantly weaker and more isolated than it was a year ago. However, it has bolstered supremacist violence, expanded the space for hardline rightists in mainstream politics, and demonstrated the political power of internet memes and coordinated online attacks. The alt-right remains a significant political force, which could either rebound or pave the way for other incarnations of far right politics. Andrew Anglin and other in-your-face trolls have been the most public face of past alt-right efforts. But in the years ahead, it is strategic thinkers such as Hood and Lawrence who represent a greater threat.

- Matthew N. Lyons, “Ctrl-Alt-Delete: The Origins and Ideology of the Alternative Right,” Political Research Associates, January 20, 2017.↩

- Lyons, “An Alt Right Update,” Poliitical Research Associates, August 7, 2017; Michael Edison Hayden, “Is the Alt-Right Dying? White Supremacist Leaders Report Infighting and Defection,” Newsweek, March 5, 2018; Shane Burley, “The fall of the ‘alt-right’ came from anti-fascism,” Truthout, April 7, 2018.↩

- Shorty Dawkins, “Yes, The Tide is Turning Against the Globalists,” OathKeepers, June 25, 2018; “Yep, Even Donald Trump Serves the Jews,” Vanguard News Network, April 14, 2018; “anp Report for January 27, 2018,” American Nazi Party, January 27, 2018.↩

- Hubert Collins, “Time for More Travel Bans,” American Renaissance, July 1, 2018. ↩

- “America First Banner Drop,” Identity Evropa, December 5, 2017. ↩

- Marcus Cicero, “President Trump Pulls Off Excellent Peace Talks With North Korea,” Occidental Dissent, June 12, 2018.↩

- Hunter Wallace [Brad Griffin], “Mitt Romney: Trump’s First Year Was ‘Very Similar To Things I’d Have Done My First Year,’ ” Occidental Dissent, May 2, 2018. ↩

- Hunter Wallace, “Trump Administration Reverses Obama Affirmative Action Policy,” Occidental Dissent, July 3, 2018; Cicero, “President Trump Pulls Off Excellent Peace Talks With North Korea.” ↩

- Andrew Anglin, “Trump on Putin: ‘He’s Fine. We’re All Fine,’ ” The Daily Stormer, July 6, 2018. ↩

- Hubert Collins, “The ice Fight Against Criminal Aliens,” American Renaissance, June 20, 2018. ↩

- Jared Taylor, “Human Shields on the Southern Border,” Podcast, American Renaissance, June 22, 2018. ↩

- Huntley Haverstock, “Mexicans & Motherhood,” Counter-Currents, June 2018. ↩

- Andrew Anglin, “ice as Trump’s Praetorian Guard?” The Daily Stormer, July 5, 2018. ↩

- Federale, “Trump Foes, Friends Fighting It Out At uscis—Director Cissna Must Weigh In,” VDare, May 25, 2018.↩

- R. Houck, “Law Enforcement & The Hostile Elite,” Counter-Currents, June 2018. ↩

- Gregory Hood, “Aprés Ocasio-Cortez, le Deluge,” American Renaissance, June 28, 2018. ↩

- James Lawrence, “Thoughts on the State of the Right,” Counter-Currents, June 2018. ↩

Addendum – A note about Proud Boys and Patriot Prayer I want to add some brief comments about Patriot Prayer (PP) and Proud Boys (PB) in light of the August 4th confrontation in Portland, Oregon, when a Patriot Prayer rally faced off against a larger counterprotest—until the counterprotesters were violently attacked by police. Joey Gibson’s Patriot Prayer and Gavin McInnes’s Proud Boys were both founded in 2016 as part of the wave of right-wing enthusiasm surrounding candidate Donald Trump. The two organizations are not identical, but they represent similar politics and have become closely intertwined. They offer a slightly sanitized version of right-wing racism. Both organizations have longstanding close ties with white nationalists and are staunchly anti-Muslim and anti-immigrant, yet they disavow explicit white supremacist ideology and include small numbers of people of color as members. Both groups uphold patriarchal ideology and glorify political violence. Unlike alt-rightists and other white nationalists, Proud Boys and Patriot Prayer do not advocate a white ethno-state or a radical break with the U.S. political system. Rather, they want to reassert white male dominance within the existing system. As “The Grouch” put it on the antifascist website Its Going Down: “what they want most of all is to be called on by the State in order to attack perceived enemies of the existing social order. Chiefly this means social movements in the streets, but also journalists who are critical of Trump (or the Proud Boys and the far-Right), migrants, people of color, queer and trans people, and so on.” Unlike the alt-right, Proud Boys and Patriot Prayer are solidly and unambivalently pro-Trump. Patriot Prayer and Proud Boys are currently engaged in a drive to rebuild the kind of broad coalition of right-wing streetfighters that operated for several months in 2017. This coalition encompassed alt-rightists, neonazi skinheads, and other white nationalists, alongside “alt-lite” Trump supporters and Patriot movement activists. The effort fell apart in the wake of Charlottesville, amid in-fighting, deplatforming by media companies, and mass antifascist resistance. So far the revival of a right-wing streetfighting force has been limited to the Pacific Northwest. Continued militant opposition is needed to shut it down and keep it from spreading. Yesterday’s events in Portland, like previous confrontations, indicate a close, friendly relationship between Patriot Prayer/Proud Boys and the police. As The Grouch commented, despite the fact that militant rightists are perpetrating more violence than their opponents, police look on right-wingers “as a group of victims, and anyone that stands up to them as instead a group of criminals and terrorists.” System-loyal right-wing groups such as Proud Boys or Patriot Prayer are better positioned to develop a collaborative relationship with the police than alt-rightists or neonazis, who don’t accept the existing system as legitimate. However, the intricate ties between Patriot Prayer and Proud Boys on one hand and white nationalists on the other underscores that we can’t treat the dividing line between system-loyal right and oppositional right as rigid or fixed. This is a dynamic situation, and I would not want to predict how things will develop from here.

Sources:

The Grouch, “In Portland, Patriot Prayer & Proud Boys Want Immigrants Heads ‘Smashed Into the Concrete;’ Gave Nazi Salutes While Screaming Racial Slurs,” Its Going Down 5 July 2018, https://itsgoingdown.org/in-portland-patriot-prayer-gave-nazi-salutes-while-screaming-racial-slurs/

“Unite the Right, Patriot Prayer, Joey Gibson, & the Proud Boys,” Its Going Down, 2 August 2018, https://itsgoingdown.org/unite-the-right-patriot-prayer-joey-gibson-the-proud-boys/