Jasmin Mujanović charts the history of the wrestling profession, McMahon's monopolization of the industry and the precarious and sometimes devastating nature of wrestlers' labour.

Wage Labour on the Fringes

For all the attention it received, to my knowledge, no one provided much of a political analysis of Darren Aronofsky’s 2008 award-winning motion picture The Wrestler. I suspect this is largely a function of the subject matter of the film: professional wrestling has been a long standing punch-line, after all. Its participants are popularly known as ‘roid popping, juice monkeys and its fans are beer-swilling, inbred country yokels. Regardless of the accuracy of such assessments, the more substantive impact of such an opinion is that it de-politicizes the given subject matter. No human phenomenon is apolitical—not even professional wrestling.

Consider the main characters of The Wrestler: Randy “The Ram” Robinson and his sometime love-interest, the stripper Cassidy. Randy was a major superstar in the 1980s, selling out arenas and performing in front of thousands, but today is forced to live out of a trailer and perform in high school gyms. His body is a wreck, and Randy is increasingly forced to rely on drugs and steroids to make it through his matches. Cassidy, a one-time femme fatale, is likewise discovering that age has left her destitute: she is a single mother, she is barely making enough to support herself and her son, and is discovering that her body, her means of income, is no longer the commodity that it once used to be.

Both Randy and Cassidy live on the fringes of society: they are employed in sectors which are regularly mocked and derided, and their personal lives, much like their physical bodies, are ravaged by scars. They are, in truth, the truest representation of the wage-worker as portrayed by Marx. They have no means of income, no means of survival, nothing to sell but their bodies and the labour these bodies can produce. And so they sell them, for decades, and when their bodies are exhausted they are left in poverty.

"...and I'm telling you that the Labour Theory of Value more accurately determines the true cost of commodities!"

The film is a commentary on capitalism. Anyone who has read Barbara Ehrenreich’s Nickled and Dimed or Ben Hamper’s Rivethead or, for that matter, worked a day in their life should implicitly recognize what wage-labour is and what it does to both the human body and the human condition. They should also recognize the incredible prejudice that working class people have historically had to deal with. If we look at the contemporary debate surrounding migrant workers we see many of these themes alive and well, and returning with some of the most vicious elements of this prejudice: they are “illegals”, “aliens”, “un-American”/“un-Canadian”/“un-European”, carriers of disease, criminals etc. The mould that was once applied to, say, Irish or Black workers and migrants has today been applied seamlessly to Latino, South-East Asian and African workers and migrants. In short, being a working class person was (is) associated with idiocy, with poverty—with many of the very attributes associated with professional wrestling fans who themselves are overwhelmingly working class.

The sectors of the economy where these attitudes are still most acutely felt are those on the margins. We see that any sector where labour standards are not enforced stringently soon become exposed to the true nature of the capitalist system; that is, unmitigated exploitation. The history of wage labour is evidence of this fact. Today, sex trade workers are prime example. In the past two decades, for instance, thousands of women have disappeared from the streets of Canada. Predators and serial killers like Robert Pickton essentially have free reign to target these women (and men, and yes, children). As participants in an unregulated sector of the economy, sex trade workers have struggled for economic security, physical security and legal recognition. Their struggle has been one mirrored by many migrant workers, often forced into slave-like conditions, as authorities turn a blind eye.

Spandex and Union Busting

One of these dark, some say “weird”, fringes is the world of professional wrestling. The death toll for professional wrestlers is not on the level of sex trade workers, but for a billion dollar industry, with millions of fans around the world, the numbers are nonetheless shocking. Since 1985, well over a hundred professional wrestlers have died before the age of 65—many of these due to drug overdoses, suicide and heart failure (a symptom of prolonged drug use). Commentators have referred to this as wrestling’s “dirty little secret.”

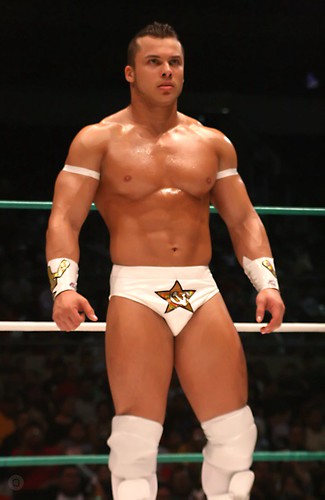

Since the high-profile deaths of Eddie Guerrero and Chris Benoit, the largest wrestling company in the world, World Wrestling Entertainment (WWE) has instituted their own drug-testing policy and on several occasions suspended talent who were found to have failed these tests. The policy has not been without controversy, as for years rumours have circulated that top-tier talent has been “protected” from testing. Moreover, as evidenced by the steroid scandal that rocked the company during the early 90s, this is not the first time that the company, and the entire industry, has come under fire for the prevalence of drugs. Even a cursory examination of the roster of top stars in the industry at any given moment would strongly suggest that bigger has always been better. Indeed, Vince McMahon, long-time head of the WWE, has amongst fans always been known as preferring “hosses”: larger-than-life, muscular individuals whose actual ability to perform in the ring was secondary. Hence, up and coming talent have always had a clear indication of what the keys to success were—and rarely were those something which could be achieved without “a little help.”

But the structural problem has remained unaddressed: why do so many wrestlers turn to drugs in the first place? Other professional athletes, even if occasionally busted for steroid use, are not dying near anywhere the same numbers as wrestlers. The answer is the nature of the industry, its unregulated character and the sheer exploitation which wrestlers face. The matter can be described succinctly: “While the outcomes of the matches are pre-determined, the effort to put on those matches takes a huge toll on their bodies. The wrestlers are on the road over 300 days a year and unlike other athletes, they do not have an off season. In addition, accidents do happen and injuries occur. Unfortunately, if wrestlers take time off, their wallets will suffer significantly. These factors all lead to the deadly slope that many wrestlers have found themselves facing. They get addicted to pain killers to numb the pain. This medicine keeps them too lethargic to wrestle, so they take drugs to get high. This deadly mixture leads to illegal drug dependency that many wrestlers have to cope with even after they retire.”

What’s more, like any large corporate empire, the WWE has gone to significant lengths to break up any potential emergence of a union for professional wrestlers. When Jesse Ventura, former wrestler and Governor of Minnesota, attempted to start such a union in the 80s, McMahon quickly put a stop to it. Still today, Ventura claims that the “Immortal” Hulk Hogan was instrumental to breaking up this attempt—arguably the most popular wrestler of all time, and one who was implicated in the steroid scandal in 90s but steadfastly defended by McMahon.

Jesse Ventura: governor, lunatic...communist?

For his part, Darren Aronofsky has called on wrestlers to become part of the Screen Actors Guild (SAG), arguing that “the problem starts with the fact that [pro-wrestlers are] not organized and they’re not unionized. That’s the main problem. I mean, there’s really no reason why these guys are not in SAG. They’re as much screen actors as stuntmen…They’re in front of a camera performing and doing stunts, and they should have that protection…Why doesn’t SAG help get these guys organized? They’re on TV performing. Or, if they’re not even on TV, the ring is a theater. So they’re not just screen actors, they’re theater actors. They’re performers. They should have insurance and they should have health insurance and they should be protected.”

But the McMahons have resisted such moves fiercely. In fact, they have for years maintained that their performers were not, in fact, “employees” but “independent contractors” and thus legally prevented from forming unions. In 2008, three former WWE “contractors” filed a lawsuit against the company on these grounds, but the case was eventually thrown out of court. Two years later, one of these men, Chris Kanyon, committed suicide.

Recently, however, the issue has come up again. When Vince McMahon’s wife, Linda McMahon, attempted a run at the US Senate in 2010, running of course for the GOP, she lost to Democrat Richard Blumenthal. But during the campaign, so called “worker mischaracterization” once again became an issue and the WWE and the McMahons were once again implicated. As of April of this year, Blumenthal has again promised to investigate the issue (with support from organized labour within the construction industry, were similar practices by crooked employers have been popular). Should these investigations evolve into something more than Blumenthal scoring points against a political opponent, it might represent the best hope for wrester’s to improve their collective lot in decades.

A Short History of Wrasslin’

Believe it or not, professional wrestling has still more commentary to provide on the nature of capitalism. To this end, something on the origins of this industry is necessary.

The first modern pro wrestling bouts were essentially carnival acts. Much as one would have bearded ladies and double-headed kittens in jars at the local fair, wrestling matches were a frequent staple of early carnival acts. Much as with the ladies and the kittens, they were advertised as being completely on the level—a travelling champion would take on all comers, usually local strong men, who were in turn usually paid to take the dive.

The notion of the “dive” or “doing the job” as it has since come to be known came out of the simple realization on the part of promoters that actual fights were entirely too risky a monetary venture (and often incredibly boring). As anyone who is even remotely familiar with casinos should be able to tell you: the house never loses. This was the same premise behind “rigging” these fights.

Moreover, in 1908 something happened that shocked the conservative, white sports world: Jack Johnson became the first black world heavyweight champion in boxing. White America was in an uproar, and there emerged the idea of the “great White hope”—a desperate search for a white boxer to defeat Johnson. Johnson would hang on to the title until 1915 when he would lose it to a young upstart named Jess Willard in a bout that was staged in Havana, and promoted by a man named Roderick James “Jess” McMahon. McMahon was to become the patriarch of the McMahon family, his grandson Vince, of course, being CEO of the behemoth that is the (WWE). Money always such interesting roots, doesn’t it?

The Johnson debacle crystallized a number of things: on the one hand, actual fights were horribly unpredictable. Staged bouts, on the other hand were safe, and could be evolved to month, even, yearlong programs and feuds. The drama “real” sporting events sought so hard to create was usually undone by inopportune victors and losers. Staged, scripted events would simply not have this problem.

On the other hand, however, there was money to be made in “bad guys.” White America’s hatred of Johnson was a boon to the boxing industry. Over twenty thousand people turned out to see Johnson take on James Jeffries in 1910, the man who declared that his victory over Johnson would prove the superiority of the white man over the “Negro.” Johnson won, and White America was livid. However, Johnson earned three figures for the fight—and thousands kept turning out in the hope of seeing him defeated. Another twenty thousand turned out in Havana in 1915—Johnson was a draw, whether it was permitted to say or not.

These two points would go on to form the bedrock of what has become known a pro wrestling: scripted fights and simple antagonisms between “good guys” (faces) and “bad guys” (heels).

By the middle of the 20th century, pro-wrestling had become a staple entertainment commodity. Cities like New York, Chicago, Philadelphia, Toronto, St. Louis, Charlotte and Memphis would over time become Meccas of wrestling and each region or “territory,” as they would come to be known, gave rise to its own promotion(s) and champions. An obvious problem resulted, however. All of a sudden there were dozens of individuals claiming to be world champions. Clever promoters realized there was more money to be made in having one world champion who would take on all comers and be a national sensation rather than a dozen regional celebrities.

With that in mind, several of these promoters came together in 1948 to form a “governing body” of pro-wrestling in North America: the National Wrestling Alliance (NWA). In turn, they also created the NWA World Heavyweight Championship (aka “the ten pounds of gold”). The possessor of this title would be recognized as the undisputed world’s champion and would tour the territories of the affiliated promoters and take on their top talents, thus drawing bigger crowds. The champion, accordingly, was decided by a vote of the NWA Board of Directors based on who they thought could draw the most money.

For next few decades, the NWA territory system functioned quite well. Guys like Harley Race, Ric Flair, Terry Funk, and Dusty Rhodes toured all over the US and Canada while promotions like Georgia Championship Wrestling, Smokey Mountain Wrestling, and World Class Championship Wrestling, to name just a few, managed to carve out their own individual empires in their respective regions. The NWA established a collection of monopolies which, respecting “tradition,” stayed within their own borders and prevented inter-promotional wars. For the most part, everyone was happy with this arrangement. After all, even though companies like WCCW were essentially reduced to running shows strictly in Texas and parts of the Southwest, they were making money hand over fist. The Von Erich family (the owners of WCCW), for instance, were icons in the Houston area.

In 1982, however, all this would change. There had been some successful outliers to the NWA from the beginning, most notably the American Wrestling Alliance (AWA) and the World Wide Wrestling Federation (WWWF). Yet while the AWA and WWWF recognized their own world champions, they still largely had amicable relations with the NWA and talent exchanges were frequent. But in 1982, a young Vince McMahon Junior bought the WWWF from his father, Vince McMahon Senior. McMahon the elder had been a promoter in the mould of the NWA, a man largely respectful of the traditions and customs of the wrestling industry and eager to avoid conflict with his competitors. Junior, however, had a different vision. He wanted to take the WWWF global.

By the end of the decade, the WWWF had become the World Wrestling Federation (WWF), and had exploded across the world in a manner previously unheard of in the industry. McMahon began hosting massive cable and pay-per-view spectacles like Wrestlemania (1985) and the Survivor Series (1987) which were seen in millions of homes and, likewise, made millions for the company. He negotiated exclusive contracts with cable providers, forcing all competitors off the air, and in the process offering their talent contracts to “jump ship” which their previous employers could never hope to match.

The last hold-outs of the McMahon empire were consolidated in 1988 in a new promotion, owned and funded by the media mogul Ted Turner, which become known as World Championship Wrestling (WCW). In September of 1995, WCW would revolutionize the industry when they were granted, by Turner, a live, initially one, then later two hour, Monday night primetime slot on TNT. The WWF had, had a Monday night program (Raw) since 1993 but it was a taped show and had done little to “grow the brand” as such. Nitro (as the WCW show was called) and Raw, and WCW and WWF as a whole, were thenceforth locked in an actual blood feud that could only end with one company going out business. While Nitro would defeat Raw in the ratings war for a startling 84 consecutive weeks, by 2001 McMahon had successfully managed to buy out his competition once more.

The Monopoly of Capital

Since then, the WWE changed its name again (resulting from a lawsuit from the World Wildlife Fund) and has become a publicly traded media empire worth billions: the latest installation of the Wrestlemania spectacular (emanating from Atlanta, the former home of WCW) drew over 70,000 fans and made millions for the company in a single night. The WWE has numerous television programs, its own film studio, and has increasingly been branding itself as an “entertainment” company rather than merely a “wrestling” company. Its closest competitor Total Non-Stop Action (TNA) Wrestling (along with their moronic moniker) has struggled to draw even fraction of its audience.

And they say the Left just isn't "sexy" anymore...

This short history of the industry should make one thing clear: it is the history of capital. From its earliest beginning, promoters were driven by profit, by greed and by the monopolistic logic of capitalism. With the arrival of Vince McMahon on the scene in the early 80s, the industry began a process of consolidation, from petty bourgeois to big capital. McMahon destroyed his competition, and the name WWE has become synonymous with pro-wrestling itself though hundreds of smaller entities continue to exist in the US, Canada, Mexico, Japan and Europe. Fans who remember the so-called “golden age” of the “Monday Night Wars” and even the period of the 80s and 70s, bemoan the state of wrestling today: an industry dominated by one brand, which produces a product largely devoid of content or quality but still draws millions as it has increasingly been marketed towards children (rather than to young adults, in particular, as had been the case in earlier periods).

The biggest challenge facing the McMahons today is the UFC, which while involved in actual sports rather than “sports entertainment”, has taken a large chunk out of the WWE’s pay-per-view revenue. It remains to be seen whether this competition will take on quite the same character as the one with WCW, though it seems unlikely (and in any case, one which the WWE would likewise be unlikely to win, at least, if the UFC continues to grow at its present rate). However, like Coke and Pepsi, like Microsoft and Apple, the WWE and UFC, while ostensibly engaged in competition, remain empires in their own right and are likely to remain as such—while posturing as “diversity” in the marketplace.

All along this process, the WWE (and most of its historic competitors) have continued to promote storylines that have only entrenched its standing as a “performance art” founded in gratuitous violence, sexism, homophobia and racism—thereby consolidating the aforementioned stereotypes of wrestling fans as inbred yokels. And yet, at the heart of it, there is little within the essential form of pro-wrestling itself that need demand this. No more than football fans need be rage-fuelled hooligans, as I have written before. Yes, it based in “violence” but so are many other sports, and the violence in wrestling is largely simulated. At its heart, it is simply athletic theatre: good vs. evil, the thrill of competition. It simply embraces as its soul what most other sports seek develop through accident: drama. As such it is little different from the film industry, and why Aronofsky was quite astute in his call for pro-wrestlers to be included in the SAG.

To that end, smaller companies like Ring of Honor (ROH) have increasingly moved away from the crass (or “crash” as it was known in the 90s) model of the WWE and prompted storylines advanced almost entirely through the simple athleticism of the in-ring performers (thus, largely restoring the “sport” element to the “sports entertainment” equation). But while ROH has garnered a cult following among fans, it is peripheral phenomenon to the dominance of the behemoth of the WWE and all its corrosive elements.

As pro-wrestling has grown to unheard of heights, it has still remained trapped within a conceptual bubble. This bubble has largely serviced promoters and come at an incredible toll to the talent. It is unlikely that wrestling will ever be embraced by the larger public, and will always remain something of a fringe phenomenon. While it is interesting to discuss the politics and economics of this process, what is more urgent is a need to take care of the human beings employed within this industry. We have come to understand the exploitative nature of capitalism, and the way it permeates most every facet of our world. While certain industries or sectors may not employ as many individuals as others, and may have a sordid reputation in one way or another, these people still require protection and they deserve rights. The women and men of the pro-wrestling industry are no different. And like the passionate football fans who have tried to save their clubs from creeping corporatization, passionate wrestling fans have a role to play in this process too—their voices and support can improve working conditions and save the lives of the talent who have broken their bodies in the process of entertaining them.

Written by Jasmin Mujanović, 2nd May 2011.

Comments

deleted

deleted

I really liked this article.

I really liked this article. Thanks for uploading it.

Yeah, I read this recently

Yeah, I read this recently and wanted to post it here but haven't had time so thanks very much!

Ditto the above - found this

Ditto the above - found this really interesting, both politically and as a wrestling fan.

ooh lookin forward to readin

ooh lookin forward to readin this :)

Wrestling is not about

Wrestling is not about victory like boxing, its theatre, drawing the audience into a melodrama and parochial sentimentalities, often a parody of socio/economic conditions, creating heros and villians depending on the social and political climate. The capitalists in Hollywood even made Rocky3 a cold-war drama, but real boxing is never about politics, its about winning.

Rocky 4 mate, not Rocky 3

Rocky 4 mate, not Rocky 3

Boxing is never about

Boxing is never about politics? What about the frantic search for a "great white hope" who could beat Jack Johnson and thus reestablish the supremacy of the white race? What about Muhammad Ali going to jail for defying the draft?

On a related topic, ESPN has

On a related topic, ESPN has an article on the low pay of UFC fighters.

Choccy wrote: Rocky 4 mate,

Choccy

Oops, yeah

.

Peter

True, but not a rehearsed or scripted political parody. ''The great white hope' was a publicity stunt to sell more tickets, and Alis house arrest was driven by religious conviction. What I should have said was that 2 boxers facing eachother only see a biological muscle machine controlled by a conquest driven consciousness opposite them. Taxes, elections and foreign policy are the last things on their minds. They are there to punish any who attempt to rise up and oppose them. In a way they are individual anarchist wrecking machines (with a heart)

Quote: On a related topic,

Thanks, Pete. As an MMA fan it was very interesting reading.

The stuff in Peter's link

The stuff in Peter's link about the MMA wages and their monopoly is really interesting.

'the Fertitta brothers have had a contentious history with organized labor.

"Station Casinos is an extremely anti-union company. It has been running an aggressive and nasty anti-union campaign," said Ken Liu, research director for the 60,000-member Culinary Workers Local 226 in Las Vegas.

For years, the Culinary Workers Union has been trying to organize service industry employees at the Fertitta-owned Station Casino properties, which largely cater to the local market in Las Vegas.'

If you're interested, the No Holds Barred podcast talks about this stuff a lot, esp the Culinary Workers Local 226 and their various disputes. That show is pro fighters union and although we wouldn't agree a lot of the hosts conclusions, it informed me about various disputes I didn't no about.

And me, more wrestling

And me, more wrestling articles!

Some reactions to the ESPN

Some reactions to the ESPN piece on UFC pay from my favourite MMA site Bloody Elbow, here, here and here

For what is generally a fairly liberal site the reactions from both writers and commenters at Bloody Elbow have mostly been pro-UFC with a common theme being that low fighter pay is necessary so Zuffa can invest in expanding MMA.

Somewhere in one of those articles it's suggested that the UFC pays its fighters only about 10% of its revenue compared to the ~ 50% that the UFC claims and other US pro-sports actually pay the players.

http://bleacherreport.com/art

http://bleacherreport.com/articles/1110575-wwe-news-wrestlings-risks-warrant-a-labor-unions-rewards

Really interesting, if long; goes into a fair bit of depth on the legal, health and political issues around workers rights in the wrestling industry, as well as quotes from prominent wrestlers and union leaders/organisers, bits of history, etc.

Hmm...

Hmm...;)

Here is a brief discussion of

Here is a brief discussion of the political economy of the Wrestler.

not sure if anyone here

not sure if anyone here follows WWE, but...

they're currently running a storyline in which Jack Swagger has been taken in by Zeb Coulter (aka Dutch Mantell) and become a hardline "American patriot" ala the Tea Party - replete with "Don't Tread On Me" flags, anti-immigration rhetoric, etc.

Subsequently they've produced extremely xenophobic promos from Swagger and Coulter, references to Swagger being a "real American", and putting him in a feud with a Mexican wrestler (Alberto del Rio). The way they're playing it is that del Rio is the face (good guy) while Swagger is the heel (bad guy) - with announcers regularly calling Coulter/Swagger xenophobic and sometimes calling them racist, tho with usual liberal provisos about "freedom of speech" et al.

this has been recognised by the Tea Party movement itself, to the point that Glenn Beck had a bit of a tantrum about WWE demonising Tea Party. They responded (in publicity stunt fashion obv) by offering Beck a spot on Raw in which he could address them - tho he refused.

Why John Oliver is calling

Why John Oliver is calling for WWE fans to protest at WrestleMania

wojtek wrote: Why John Oliver

wojtek

Half-watched that. It was a bit surprising to see Oliver saying he's a fan, as I find it mostly asinine as far as entertainment goes, and the people who are into it mostly unsavory, or right-wingers, or both - the Jim Sterling guy is surprisingly into it as well (I think). I don't really get it...

I remember Chris Hedges writing something politically about it in his Empire of Illusion: The End of Literacy and the Triumph of Spectacle. Don't recall all he wrote there (he's just some liberal of course), something along the lines of it being an idiotic form of distraction and reinforcement of people's values/beliefs, such as pro-capitalist and nationalistic beliefs (see for example the

"communist" "Nikolai Volkoff" portrayed as the bad guy up against the patriotic "Hulk Hogan", etc.)

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=dc7_lbEirnA

Mujanović wrote: What’s more,

Mujanović

Not sure how seriously this is supposed to be taken, but Ventura being depicted as some labor-organizing commie is just farcical: he has right-wing libertarian sympathies and endorsed Ron Paul and Gary Johnson, describing himself as "socially liberal and fiscally conservative", as well as going on Alex Jones' show expressing doubt about 9/11.

Ventura on Johnson:

Ventura

Mujanović

I'm not sure what "being a working class person" means here. My only guess is that the author doesn't know that office-type workers are also part of the working class, and that class has nothing to do with whether or not your wear a suit to work. The comparison of the ~200 or so "poor, abused performers" (mostly rotten people honestly as the article points out, with scripts based in "violence, sexism, homophobia and racism") to the millions of migrant wage-laborers who face real struggles is just insulting to say the least, especially considering these "performers" have average salaries of ~$500,000.