A text from Hamilton, Ontario, discussing the state of play with gentrification in 2015, as well as the role of art and progressive urban planning in contributing to "regeneration". The tensions discussed in this text would later lead to the Locke Street affair of 2018.

This text is available as an imposed booklet pdf for easy printing

Introduction

For the past several years, we’ve been talking quite a lot about gentrification here in Hamilton. In the current moment, as the vanguard of art galleries decisively give way to boutique shops and condos, as sections of town are repurposed into bedroom communities for people who work in Toronto but can’t afford to live there, what do we mean when we talk about gentrification? Two years ago, even the arts industry fucks could claim, without feeling too dishonest, that they were creating something local and durable. Now we watch their flagship galleries and favourite restaurants close while a Starbucks and McMaster satellite campus open in Jackson Square, with condos going up on all sides. You were the footsoldiers of gentrification – don’t say we didn’t warn you.

What is the relationship between gentrification, culture, and development? How do issues of transit, climate change, and population growth enter in? How does an anarchist approach to these issues go beyond the good progressive urbanist line of rent control, land trusts, free transit, and affordable housing? In this context, can we imagine an urban space worth fighting for, or is it, like our friends write in Salto, that “the urban horror … is so engrained that in order to reclaim the city as a project to nourish free lives, we would have to destroy it down to the last stone.”1

We are not writing this to participate in a conversation about what development in Hamilton should look like – development is not a conversation, it is an attack. As a starting point, let’s remember that gentrification in Hamilton does not represent a change in the way power works in this town. All that’s happened is a central fact has been laid bare – that we never actually had control over our neighbourhoods. This might be the answer to why, after years of talking about gentrification, we’re no closer to an effective way of fighting back – we’ve been aiming at the symptoms, not the root causes.

For all that we might feel connected or rooted in our neighbourhoods, we are only permitted to be there while it’s convenient for those who actually control the areas we live in. But a strong wind is blowing now, and it turns out our roots here are shallower than we might have believed…

In this essay, we take aim at the progressive urbanists who work to dress up development as a public good. Although obviously it’s the developers and politicians who are the underlying problem, it’s usually the urbanists, people who are passionate about downtown “revitalization”, who push back when we set out to critique development downtown. Their visions of livable cities provide cover for the developers and justification for all the displacement and suffering urban redevelopment schemes cause. We need to push back against these ideas and put pressure on the groups and individuals who support them. By doing this, we can isolate those few who actually support the ability of capitalists and politicians to profit by reshaping our neighbourhoods.

Some Definitions

A simple definition of gentrification might be that it is a process whereby one group of people in an urban space is displaced by another that is considered more desirable (which usually means more profitable), and it is also the creation of the physical, social, economic, and political infrastructure that makes this displacement possible. Urban space can be understood in many ways, but for this essay, it’s important to remember that a city is a density of people and infrastructure that allows capitalists to increase their profits from the land and from the productive facilities they control.

Cities are mostly populated by alienated people, uprooted from any sort of traditional connection to community or place, with little control over their living conditions, and who are either useful to capitalists or are considered marginal and are therefore to be controlled and managed. Gentrification is one way that the rich and powerful rearrange urban space: to get the useful people where they need them and keep the marginal ones under wraps and out of the way.

In Hamilton as elsewhere, when we try to engage with gentrification, we usually end up in conflict with progressive urbanists long before we confront capitalists. These are the people who talk about urban revitalization, smart planning, liveable cities, poverty alleviation, social entrepreneurship, the creative class, and other clever-sounding rebrandings of a very old story. In general, urbanism is the study and design of urban space, usually with a goal towards improving in some way the lives of people who live in cities. Salto offers a different definition of urbanism: “Urbanism seeks to reproduce social hierarchies in the physical urban space, without conflict.”

When urbanists talk about improving lives, they are usually talking about projects designed to mask the contradictions of capitalism and of urban space: if we are to be an uprooted and flexible workforce, at least let there be affordable public transit so the commutes we are forced to make aren’t too much of a burden; if we are going to work minimum wage jobs, let there at least be housing we can afford; if we are going to live in crowded, oppressive conditions, at least let there be public art, good services, and native tree species slowly dying in roadside planters. However, as we get bedbugs from our library books and are hit by cars in the bike lane, we remember that these gestures are actually shit. They are meant to ease the discomfort caused by the purpose of urban space – to provide a density of physical and human resources to maximize value for capitalists. And once an area becomes a comfortable one in which to be exploited, you can bet someone is going to pay more for it than you can.

Speculation precedes development

The story of Hamilton’s gentrification didn’t start with the GO station and the condo towers. The groundwork for much of the current boom was laid in the seventies and eighties in the form of an economic collapse in the downtown. This is the era where buildings like the Tivoli and the Lister (the former recently approved to be a condo tower and the latter redeveloped into expensive offices and boutique shops) were left to rot, to become the stinking and mysterious mazes we enjoyed exploring ten or fifteen years ago. Many building were demolished and the lots left empty or turned into parking lots – take a walk north-east from the intersection of Rebecca and Hughson, or down Barton West. Business owners fled Barton St and then King St, and the rental units nearby were allowed to decay.

Downtown Hamilton’s class identity shifted from working class to economically marginal, prole to lumpenprole: the people with the industrial jobs moved to the new sprawling suburbs and large areas of the lower city were left to broke people. Downtown is still one of the national capitals of people receiving social assistance, especially disability support. Through the nineties, social services in Toronto even paid people’s bus fare to move to Hamilton – the concentration of services downtown made this area one of the few in the (so-called) Greater Toronto-Hamilton Area that was still almost liveable for broke people. By the 2000s, as industrial collapse set in, this base of broke people would support the new dominant industries in town: health care and social service.

From a developer’s perspective, this process is called speculation. Collapsing commercial property values push small capitalists out of the game and makes it easier for larger capitalists to accumulate holdings in an area over decades, to put a plan into action once the time is right and reshape the neighbourhood – Locke St, largely controlled by a single capitalist, is the prime example of this centralized reshaping in town.

Speculation means accumulate property when times are bad, then upgrade, sell, and make crazy piles of money once times are good. In the meantime, we are allowed to live in (or in the shadows of) collapsing industrial buildings (along Dundurn St S, Barton St, and in Keith neighbourhood), infested apartment towers with broken elevators ( those around the intersection Hess St and Bold St come to mind), and disused store fronts converted with plywood into multiple unit dwellings (famously on Barton St E, but Canon St and King St E too).

From developing the arts to the art of development

Of course, this kind of collapse produces opportunities for other people as well. Many of us were drawn to downtown Hamilton by the cheap rent and the opportunities for autonomy in areas largely abandoned by capitalists. Ten years ago, the antagonistic political scene mingled with an artsy scene as well as a scene united around drug use. Some of the artists made deals with property owners to take over their store fronts for either cheap or no rent with the understanding that they would fix the place up and keep it clean. Some even bought buildings and took on the slumlording responsibilities of the previous owner or undertook renovations. By the early to mid 2000s, this process was focused in the emerging art district along James st North. (Locke st would follow a slightly different path and, being a few steps ahead of the downtown, it often served as a model or point of reference; however the options for densification that exist right downtown do not exist at Locke, so development there has been limited.)

The artists had their spaces and a community of sorts formed around them. For the most part though, this community didn’t generate any money, and the spaces relied either on grants or on the day jobs of their owners. To get out of the margins of capitalism, they would need to create an industry around themselves, and the first step in this was to transform the identity of the neighbourhood into a brand. This brand, this image of the area, was used to market their businesses to people in other parts of the city to attract them to the area for special events, notably Art Crawl2 . For these events to become larger, the reality of the neighbourhood needed to be sanitized, even as a certain edginess was still an important part of the art scene’s self-marketing. So began the partnership between the arts scene, especially its business owners and various professional associations, and the police.

For those of us who lived downtown, at first Art Crawl was a good chance to busk, pan handle, or sell things to the ever-larger crowds that appeared one day a month, but as the event morphed increasingly into a policing operation, the opportunities for this shrank. By the time of the first Super Crawl, the policing operation for Art Crawls was beginning two days in advance, tearing down posters, clearing away the usual suspects, warning people they would be ticketed under the Safe Streets Act3 if they were present in their usual spots. The artsy business owners advocated for more surveillance cameras, for the removal of sex workers, and more enforcement of minor offenses. Their shit-eating snitch lobbying led directly to the creation of the ACTION team, a community policing operation, which bases its legitimacy on regular surveys of local business owners4 .

The creation of an industry in a part of town that had previously been vacated by capital, along with the “cleaning up” carried out by the police and the business owners, created opportunities for more conventional capitalists, who at present are steadily replacing the artists. Coffee shops, restaurants, and bars took advantage of the customer base created by the artists; however, unlike the art business owners, these capitalists could actually compete in the market. So as the grants slowly dried up and rents and property taxes in many instances doubled, the artists began to be pushed out in turn. Now, as the area becomes cooler and more expensive, offices for consultants, architects, tech start-ups, social entrepreneurs, and other small “creative class” businesses replace the arts studio spaces. The remaining businesses that meet the needs of the local community are also being replaced by this sort of hip capitalism – the loss of Treguno Seeds, downtown’s only gardening store, and its replacement by a seed-themed collaborative office is truly an insult.

The influx of capital and the physical improvements carried out by small-scale developers in the core sent a message to the big property speculators that it was time to act. Throughout the downtown, abandoned buildings and vacant lots filled up with construction workers – a dozen or so condo developments are in progress. This is further fuelled by overflow from Toronto’s real estate bubble: in what may be Canada’s most ridiculous property market, developers seeking to diversify their assets (for when the bubble inevitably bursts) hear on the CBC that Hamilton is the next big thing and that it will soon be getting all day commuter GO train service, and they quickly either find partners in town or jump in themselves.

In their high-density rental buildings downtown, big landlord Homestead Holdings hands off their operations to Greenwin to evict tenants and raise rents5 . Their push to remove undesireable (meaning poor and racialized) tenants coincides with changes to Federal immigration policy and deportations become another tool to make begin replacing broke people of colour with broke white people, while making the renovations that will eventually allow them to get out of the broke people business all together.

The rising cost of living in the downtown has created a wave of economically displaced people being pushed east of Wentworth St, creating a surge in unsafe informal rooming houses and contributing to a further collapse in quality of life in Ward 3’s apartment buildings (notably on Sandford St, but this is quite widespread). The gentrification of the core has also coincided with the growth of the payday loans industry, offering loans to broke people at interest rates as high as 60%. This further misery dumped on broke people is a direct consequence of rent increases, of so-called urban renewal.

Populist leftists in that area, including the councillor, want to crack down on the manifestations of the problem – the unsafe living situation, the exploitative loans – while also hoping to cash in on its cause. Out of one side of his mouth, Councillor Matthew Green wants to go after those who exploit the poor, but out the other, he brags that Ward 3 will be Hamilton’s next economic success story6 .

Green capitalism and other scams

Some words about transit: The increasing profits of developers, the hype around a revitalized Hamilton, and the shifting demographics of the area now coincide with a wave of infrastructure investment under the guise of the PanAm Games. This has included relatively benign projects like the Cannon St bike lanes, the Social Bicycles program, and the new HSR hub on MacNab St as well as game changers like the James St North GO train station7 , the Gore Park redesign, and (further in the future) light rail transit.

Let’s not be fooled, even small projects of this sort are physical transformations designed to literally open up our neighbourhoods to investment. Though we may use the bike lanes or GO network ourselves, they are nonetheless part of a model that sees us all as uprooted subjects of capitalists, our value tied to our flexibility – by making us more flexible, more able to easily and cheaply move from place to place, we become more valuable to the capitalists while also experiencing less starkly the fact of our oppression8 .

All the green rhetoric about alternative transportation also serves to mask the contradiction that capitalism is killing the planet and making our lives miserable in the process. Ecological collapse is a crisis of capitalism and we are being asked to participate in helping the economic system survive it. Like in other crises, the richest are the most able to adapt and so will collect the profits as the poorest get crushed. The racial dimension of this process is impossible to ignore, in Hamilton and around the world. Yes, obviously it makes sense to live in ways that poison the earth less, but if we accept patchwork solutions that maintain the power structures that produced this disaster in the first place, we are being scammed.

The GO station makes this dynamic particularly clear. It opens up the North End, Beasley and Jamesville neighbourhoods as potential homes for those who work in downtown Toronto, no longer less convenient than other satellites of Canada’s financial centre, such as Oakville and Burlington. Public transit within the region is considered smart urban planning by urbanists, because they take for a given that we have no control over our own lives and will be forced to travel from wherever we can afford to live to wherever some boss is willing to pay us. Because of the ever-worsening traffic around Toronto and in the name of reducing greenhouse gas emissions, we are told all-day passenger train service is a public good. Under the guise of a supposed public good, North End, Beasley, and Jamesville residents are asked to be excited about the infrastructure producing the economic conditions that displace them.

Have you stopped and wondered why the same interests that never gave a shit about broke people in the core are now excited to make the GO Station happen? People downtown have been talking about how expensive and slow the HSR is for decades, so why is it now that powerful people are talking about LRT? The urbanist line would attribute it to successful organizing by the creative class downtown, but this ignores the fact that this lobby group didn’t exist downtown before – they all had to move here first. The fact is that transit improvements are for the wealthy and upwardly mobile or for those who share their ideology – now that those folks are here and organizing amongst themselves, of course power is listening.

As the excellent text “Against the tyranny of speed”9 asks, do we really consent for the journey between two places to be transformed into a form of waste that is to be reduced as much as possible? If we were in fact travelling freely instead of from economic necessity, would we accept any destruction of our communities in order to make a trip slightly shorter? The authors also point out that the ability to move more quickly between two places goes along with those places becoming more similar – the compression of space is also its homogenization. They ask, if all that these trains offer us is the ability to find in Hamilton the same condo towers and hip cafes we left in Toronto a few minutes more quickly, does the entire project of speed have any value?

Do we really want to be exploited in a greener and more efficient way? And will it even be the people of downtown Hamilton riding this train? More likely, it will simply open up our neighbourhoods and their cheap housing (generally, about a quarter or less the cost of comparable housing in Toronto or Mississauga) for purchase to workers from Toronto and we will join the thousands of our neighbours already shunted further east, into areas still being degraded by speculation whose time has not yet come.

When capitalists ask us to commute to work in an environmentally friendly way (to jobs that exploit us and benefit only them) as part of a solution to climate change (a problem they created and now try to profit from) the only appropriate answer is to attack all their feel-good crap in any way we can.

Right now, transit infrastructure developments are widely supported by leftists and urbanists in Hamilton, who forget that all technologies are produced by and produce in turn a specific social context, a way of life. It’s not that we want to oppose all trains, it’s that in our situation, the technology of the passenger train is inseperable from the broader questions of development, work, alienation, and environmental degradation. To simply support public transit in the absence of a meaningful attack on the economic system is to support the economic system and to strive for its improvement.

A similar critique can be made of urban densification, another common urbanist argument in favour of gentrification/revitalization. The idea is that existing urban areas need to build the infrastructure to house a greater density of people – the most progressive urbanists will add that this needs to include low-income units, and some developers will even make a token (and temporary) gesture in this direction. In Hamilton though, we get continued expansions of the urban boundary for residential use (been following the aerotropolis lately?) while also being asked to not complain so loudly about the economic impact of hundreds of condo units entering the housing market for the same price as four-bedroom houses. The same developers are happy to play both sides, arguing against environmental regulations on the city’s edges and in favour of densification in its centre. An abstract concept like densification cannot be separated from the developers and politicians who would be the ones putting it into practice.

Do we actually stand to benefit from causes like transportation and urban densification, or are they sold to us in moral terms so that we accept being swept aside by the gentrification they bring? If we understand urban space as being a concentration of value and resources that benefit the productive capacity of capitalists, then making that space denser means one of two things in a given area: either a larger concentration of productive workers makes it easier to create infrastructure for them (while also increasing property values); or the concentration of economically marginal people makes them easier to manage with social services and police (which depresses local property values and favours speculation). However, we don’t want to be managed or put to work – we are suspicious of anyone who tries to sell us these roles as though they were a moral duty.

The progressive urbanist will object that their goal is mixed-income neighbourhoods, where distinctions of class become, like race, religion, ability, or sexuality, an aspect of “diversity” to be included. The political forces and the realities of oppression that these categories describe are to be erased and replaced with a neutral idea of difference in the context of membership in a common “society”.

Remember, urbanists seek to reflect social hierarchies in urban space, without conflict. By seeking token concessions to the needs of those pushed aside by development, by framing development in moral terms, by insisting that profiteering look pretty and be environmentally sound, progressive urbanists try to soothe and conceal the obvious violence of capitalist urban development. They envision capitalism becoming a force for the common good, but there is no common good and society doesn’t exist – our identity labels describe our relationships to systems of domination that are to be destroyed, not incorporated into a mosaic10 .

Why do we tell these stories?

The purpose of retelling the story of gentrification in Hamilton is not to become indignant or to engage in a debate about appropriate development. These displacements are not themselves the problem – the real problem is our lack of control over our own lives, individually and collectively. We tell the story of gentrification here in broad strokes. Although it’s important to remember the specifics, these details are not the point. Let’s not forget which gallery owners (YouMe and the Pearl Company) set up the photo display of sex workers in order to support a “crusade” against them and which collaborate with the police to discourage postering and graffiti, or that Darko Vranich stands outside his new hotel thinking of the collapsing buildings on Hess, Dundurn, and Aberdeen that are going to make him and his son Denis even richer – but let’s also not mislabel individual assholes as being the source of the problem. Even the arts scene’s biggest boosters are quickly realizing that they were just the disposable footsoldiers of gentrification after all, and though Denis Vranich is a despicable sexual predator and scumbag developer, his role is totally interchangeable with that of dozens of other rich creeps.

We need to remember these broader contexts in order to stay clear of the false solutions we are offered by leftists, politicians, and, most sinisterly, “social entrepreneurs”. In the years of conversations about gentrification, we have been asked to lobby politicians for affordable housing, to ask for increases to welfare and disability support rates to allow people to keep up with rising costs, and to not criticise too loudly progressive developments like the West Ave school condos with its certain number of unit-years of affordable housing and in-house daycare. We’ve been told that the solution is in rent control, land trusts, and job creation. All these solutions share the flaw that they keep the real problem in place and in fact hide it from view – whether we rely on the intercession of politicians, angel investors, or enlightened planners, we still do not have control over our own neighbourhoods or over the conditions of our own lives.

The process of struggling for rent controls or against evictions can create the autonomy we need, but we gain this through the process of struggle itself, not by achieving the goals we may name. In fact, the surest way to take away the autonomy a community finds through struggle is to offer concessions on its demands – the areas of New York City long protected by rent controls (that at present have almost entirely been undermined) are perfect examples of this. As the combative, autonomous spirit fades, the gains are rolled back and the areas become subject to the whims of the economy again.

In the recent text “To Our Friends”11 The Invisible Committee reminds us that, paradoxically, the conditions we struggle to defend do not precede the act of entering into struggle. When we engage a determined struggle over any issue, but especially one very close to our subsistence like housing, we form strong relationships, gain practical autonomy in our territories, develop networks of mutual aid, exchange skills and tools, and begin to take back the daily flow of our lives that has been hijacked by capitalism. If we insist on remaining alienated and asking those in power for minimal demands like affordable rent, then the best we can hope for is to maintain our sad comforts without ever tasting the autonomy we actually need.

And what can we do?

We can produce some nice rhetoric about struggle, but what does this actually mean in Hamilton? After so many years of trying to find a way to confront gentrification, after so much talk, we need to admit that we don’t know. Mostly, all the struggles against gentrification we’ve ever seen (and certainly the most we’ve ever achieved here) have only succeeded in making the process uncomfortable for those involved. Prices go up, people are driven out, but at least we have a vocabulary to describe the situation and it’s a bit harder for yuppies and urbanists to cheerlead revitalization.

When people from Toronto remind us that they’ve been priced out of their neighbourhoods too, we have to admit that people moving to different places is not the problem in itself. As the authors of “Oakland is for Burning?”12 explain, it’s absurd to end up telling people where they can or can’t live.

A bare minimum ask we might make of people moving here (and of ourselves too) is to refuse to become the political base for developers and for gentrification’s boosters. The wave of people moving here, primarily from Toronto, has combined with the existing artsy, urban progressive space to produce a pro-development population in the core. Many people who move here get swept up in this – they’re paying twice the rent of the previous tenant or paying a hundred thousand dollars more than a house was worth a year earlier, joining on calls to clean up the neighbourhood, calling the cops on their neighbours rather than getting to know them.

Some ways to begin refusing this are to learn the histories of the neighbourhoods you’re moving to, to connect with your neighbours and build relationships, to enter slowly, understand the various interests competing in the downtown and pick sides consciously. But reducing the issue of gentrification to one of personal conscience is pretty obviously insufficient.

Although it falls far short of an organized response to development, forming relationships and discussing the issues that face us is crucial for developing an understanding of the specifics of the situation we’re confronting. In this moment, where gentrification is undeniable, we need to push back against all the false solutions to it we are offered.

We don’t need to offer some compelling vision of a happy, peaceful urban future to attack the root causes of gentrification. A purely negative approach to gentrification and development allows us to clarify our position and distinguish ourselves from the innumerable managers and profiteers who seek to cash in on gentrification: for instance, Hamilton Land Trust realized that rent increases are a great opportunity to start another registered non-profit and create jobs for the creative class by building a few rental units for the dissposessed. Probably a smart business move.13

A purely negative orientation also helps bring fault lines to the surface and force the contradictions that urbanists and leftists try to plaster over. Before being able to attack the developers and politicians, we need to pressure the urbanist and leftist scenes, to force a split in them between those who actually support development and capitalist control downtown and those who don’t. We need to dramatize the conflict that is playing out around us. In the downtown arts/progressive/whatever scene, everyone is so polite to each other, yet some people are being evicted while others are flipping their investment properties – that such a contradiction can co-exist peacefully is central to the entire idea of a “creative class”.

Especially as it becomes obvious that most of the stalwart ‘urban pioneers’ who opened up the “empty territory” of downtown Hamilton are no longer useful to capitalists and are being displaced, many of the voices that once argued against an antagonistic approach to development are being discredited. Can anyone still take Matt Jelly seriously as he “appeals to the good of the community” about Mex-I-Can restaurant closing, after he’s spent so many years spent helping along the process of gentrification?14

Often, texts critical of gentrification end with some sort of call to broad-based neighbourhood organizing. For now though, with the progressive discourse of urbanism so pervasive, offering a purely negative response to gentrification seems more attainable – hopefully, this can also clear away some of the bullshit and make the need for organizing without politicians, granting bodies, or neighbourhood workers seem more urgent.

By purely negative, we mean a total refusal of the entire urbanist project and all its details, including (but not limited to):

- Fuck your transit. It isn’t for us, and only serves to push us into regional labour and housing markets, uprooting us and putting downwards pressure on our living conditions. This is especially true of GO transit, but applies to LRT, improved bus service, and bicycle infrastructure to various degrees.

- Densification is code for condos – it’s a scam. These developments are sold to us in moral terms, but they serve the same purpose as sprawl in making the rich richer.

- Drop out of “art”. The arts scene has been the enemy of most people in the downtown for a long time now, all while pretending to care for the communities it parasitizes. Sure, create and beautify, but destroy the identity of “artist” — it just means someone who participates in the arts industry and benefits from all its filthy alliances with police, capitalists, and politicians.

- Refuse the logic of charity. Basic needs are out of many peoples’ reach – but rather than seeking to address the root causes of inequality, charity seeks to provide a minimum of subsistence while maintaining a clear division between the haves and have-nots. It is the opposite of autonomy and the opposite of struggle.

- Affordable housing is not a solution by itself – remember, gentrification is not the problem, it’s a symptom of the underlying issue. Although organizing around tenancy issues can be an important starting point, be wary of trading the autonomy gained through struggle to a politician for some limited concession and of watering down your own analysis to appear more palatable to some imagined ‘ordinary person’.

- Yes, against even the cool spots where you like to hang out. When we organize our lives around shows at yet another trendy fucking place, we are giving away our skills and energy to capitalists and developers. The cafés, the bars, the venues, the restaurants, all of these places produce the social (and, increasingly, economic) capital that drives gentrification. A boycott is not sufficient – we need a form of suicide, killing the identities we’ve built around our attachment to this scene.

- Go beyond the limits placed on our opposition. The smothering blanket of democracy offers us a certain amount of space to be critical, and in fact relies on it – by obligingly stepping into the role of loyal opposition to development, we actually contribute to its legitimacy.

In the short term, a purely negative approach might look like graffiti and propaganda targeting transit, anti-poverty, and environmental groups that seek to present development as a social good and entrepreneurial capitalism as a solution to our problems. Propaganda might build towards public meetings to discuss ideas more openly, disruptions of pro-gentrification/development events, or occupations of public space. Today, some of gentrification’s fiercest critics in town are people who, when persistently confronted with the contradictions of “revitalization”, stepped away from their former projects and positions. So far, the most effective tactics in Hamilton have been ones that drive open fissures and force belligerent, defensive responses from gallery owners and social entrepreneurs convinced that their self-interest is also good for everyone.

All this and more. Can we break our own identification with the discourses and groups driving gentrification? Can we find ways to attack urbanist and progressive tendencies and force those persuaded by them to recognize the contradictions? We hope that this analysis contributed to a clearer understanding of how gentrification is produced in Hamilton and offers some starting points for confronting it. Though it may seem scary to push open rifts in a scene, silence only serves the powerful and our quiet complicity betray our own interests. This summer, let’s embrace conflict as a creative and transformative force and confront development’s boosters no matter what mask they wear.

- 1Salto is a journal published in Brussels. This quote is from the august 2014 edition and the translation is ours.

- 2For those who might not know, art crawls are monthly events where galleries would co-ordinate their launches and collaborate on promotion to attract a large crowd to James St N.

- 3A set of laws further criminalizing pan-handling, vagrancy, and loitering. With these additional powers to arrest for crimes of poverty, police are able quickly clear out target areas. Toronto’s Queen St W was the first target of these laws, but they are now applied all over.

- 4The ACTION team are a team of bike cops who hang around ‘priority areas’ bullying broke people about nuisance crimes, collecting lists of contacts, and keeping cosy relationships with the local business associations. A critique of the ACTION team written during their early days is available here: http://toronto.mediacoop.ca/fr/story/questioning-action-team/6936

- 5Their properties on Market St were later handed off again to DMS Properties

- 6Check out the Spring 2015 issue of the GALA community hub’s newsletter to get it in his own words.

- 7For those outside the GTHA, GO is the name of the regional transit network.

- 8This is the same for other favourite urban environmental causes, like access to healthy food and decent medical care. If we eat to fuel ourselves at work, let the food at least be adequate and nutritious; if we need to stay healthy at the risk of losing our jobs, at least let the care be comprehensive and convenient. We could go on like this: if we are to live in a concrete hell, let there at least be public art and shade trees…

- 9Relevé provisoire de nos griefs contre la tyrannie de la vitesse, a text out of France analyzing struggles against high-speed rail lines as a broader conflict over modernity.

- 10Racialized identities exist in the context of a dominant whiteness and the racist state of Canada; queer identities exist relative to a smothering sea of heteronormativity; the terms ‘poor’ or ‘working class’ clearly only have meaning while there is a rich ruling class – an attempt to reduce struggles to a simple question of inclusion is an attempt to make the violence and illegitimacy of systems like white supremacy, capitalism, and patriarchy seem invisible, comfortable, and inevitable. The goal of diversity and inclusion has been largely adpoted by the economic and political elite, which is useful for silencing a leftist opposition that typically takes a few decades to notice its priorities have been recuperated.

- 11Published in late 2014 as À Nos Amis

- 12Oakland is for Burning? Beyond a critique of gentrification. Published in 2012 on Bay of Rage

- 13Land trusts are very frequently held up as potential solutions to gentrification. However, they are really just an example of social entrepreneurship stepping into the gap in the economy left by the contraction of government social service. The Hamilton Land Trust is focussing on purchasing vacant lots to build affordable housing, sharing with condo developers the goal of putting as much land in the core as possible back into the economy (and taking it away from the coyotes and red-wing blackbirds). We don’t doubt their ability to create pockets of (more) affordable rent in the midst of a condo boom, just like city housing programmes did in the past. Land trusts are at best no different than city housing, in that they become just a large landlord to the still-powerless folks in their buildings.

- 14Jelly’s by-law crawls and attempts to force action on cleaning up abandonned industrial sites are one example. Another might be his snitching on neighbourhood residents and on those critical of gentrification. Yet another would be his attempts at leveraging his notoriety into a political career. One could go on… (See Matt Jelly’s response to this in the comments on the original article)

Comments

Quote: Two years ago, even

Here's an article from from the late 1980s dealing with the same question in the US & UK; http://libcom.org/library/occupation-art-gentrification

I imagine you may well have

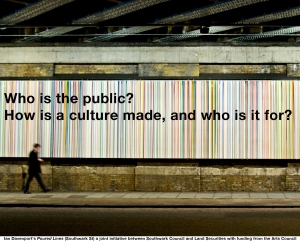

I imagine you may well have seen it, but I remember Southwark Notes' coverage of similar issues there being good as well: