An article that attempts to tie in the anti-education cuts movement with a deeper critique of the education system.

It was inevitable that, once the focusing date of the actual parliamentary vote on tuition fees passed, the ‘student movement’ in the UK would die down. It was equally inevitable that the banality-factories of liberal punditry would start wittering away, devoid of any meaningful analysis as to the extent to which it constitutes a significant change in youth organisation, or how it operates on the level of a spectacle. This media cannibalism, slowly devouring it’s own construction (do we recall the heady days of columnists asking us to ‘do a France?’) as the end point of the news cycle, is of little consequence to us.

For youth itself however, working-class youth starting to face down a year which will be defined by savage governance and social crisis, it’s probably a good time to look at how our critique of the education cuts is transforming into a critique of education itself, as it exists.

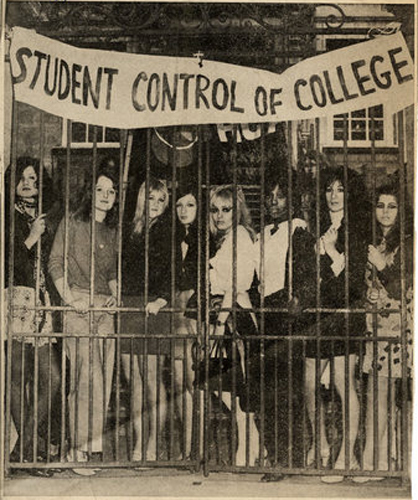

One of the Clarksonisms levelled at the student protestors was that they were, essentially, defending their own middle-class privilege. Leaving aside a much needed debate about class, as a facile criticism it nonetheless struck a chord with many of us, not because it was accurate but because it raised an important sub-question: just what are we fighting to defend? The inadequate education factories we attend, or are working towards, or have recently left? Many of us were out on the street defending an education system which we resent, for which we are full of animosity, which in no way embodies what we think education is for. We were out on the street to stop education becoming more what it already is. Banners such as ‘my students are not my clients’ are an expression of an almost utopian desire, not a statement in defence of the current situation. What did our banner, ‘WE WANT FREE EDUCATION’, really mean by free?

The problem in developing a radical critique (and hence an avenue out of the impasse of mere ‘resistance’) lies in the fact that, before these cuts and higher fees were imposed, there was an assumption on much of ‘the Left’ that the primary function of education in our society was as a public service. This illusion of further and higher education as a humanistic propagation of education for education’s sake bears little scrutiny. We see the failure of the student movement to really confront the role of higher education in the maintenance of the general intellect – that is, knowledge as the main productive force – as a very real problem in moving beyond the anti-cuts narrative and into a discussion on the creation of a society fit for humans. We say this not as a ultra-left whinge about every little bit of our life being turned into an exploitable commodity, but because it seems to us that understanding that education in our society is essentially training, is key to developing a powerful and incisive criticism of it.

So it is for this reason that we think ‘why can’t we just have learning for the love of learning’ is not an argument that cuts the mustard in a capitalist society. Of course, the Tories have been particularly tendentious and explicit in putting forward their idea that the state should only really pay for useful, profitable subjects like engineering, maths and the like. Such a position really highlights the complete stupidity of their argument, bent more by their Trumpton ideology of 1950′s Britain, with a bobby on every corner, high streets butchers with rosy-apple cheeks and the working class up t’mill or down t’pit; poor, yes, but happy in their labour, glad to know their place. The idea that our economy runs on those subjects, rather than on the service industries, media and advertising, research and development, and a cartload of other precarious ‘careers’ would be ludicrous if it weren’t so malign. It’s a policy designed to appeal to certain swing-constituencies, not to actually create a more efficient (by their standards) education system.

But for the same reason, we cannot claim that to study Art, or English Literature, or other humanities is to somehow opt out of the capitalist system for the pure love of knowledge. These educational programmes build and train workers in these industries that today provide economic flesh for the western world. We must acknowledge that those degrees are as vital in providing the skills needed for the reproduction of a capitalist economy based on immaterial and cognitive labour as engineering or modern foreign languages. Aspiration is not insignificant here. Few estate agents, call-centre managers or system designers actually get a degree in that area specifically – few would necessarily want to, such is the remaining power of aspiration over the university system. Rather, whilst they study arts and humanities, they accrue the necessary transferable skills that will subsequently become economically useful – this is where the real value lies. We barely need mention the proliferation of services and arrangements universities today offer to students to explicitly ready them for the labour market. These are the reasons the surface readings of “education should be free” are wrong- they are the calls of the established left wishing to return to the days of the social-democratic truce, days as romantic and reactionary as the Tories image of “Big Society”. Days of fordist industry, strong unions, men with big muscles using hammers and drinking tea somehow being the only path towards Good Old Socialism.

So the first step we must take is developing our critique is to make it explicit in terms of our relationship with the economy today. What the fees symbolise is a very real wage-cut in exchange for providing the economy with a higher skilled, more adaptable, less secure, more indentured workforce. We are being made to pay for our own training, with no guarantee, and often little chance, of a corresponding increase in pay. A university degree today is not a sign of becoming middle-class. It’s a way for the working class to make themselves suitable for the post-industrial workplace. This must be the basis of any class analysis of the current argument. A student movement without a radical discourse is trapped, stuck with it’s populist ‘radical’ rhetoric but without questioning capital directly, arguing only for a more humane management of capital: crumbs from the table of production.

Despite our own rhetoric, this shifting is happening not because the Tories are naturally bad people (they are, but that is just a coincidence). This position has arisen because for a variety of reasons, only one of which was the bank bailouts of the past 3 years. To claim the reason we cannot afford universal education is due to the banks confuses two concurrent symptoms with a cause and effect– it is populist left-wing grandstanding which appeals more to hearts than minds. The marketisation of higher education happened long before the current financial crisis. Both are the result of a tension, a crisis in capitalism developing from neoliberal market reforms – but a crisis that neoliberalism is ruthlessly exploiting in order to consolidate more rights, more wealth and more power. This was a blip, not a rupture, and if things go to plan, we’ll arrive the other side without even those basic social-democratic gains of the past century.

What we are building is another question entirely, but the alternative we work towards will have to contain the seeds of the disruption and destruction of that which already exists. Toni Negri asks whether ‘we might consider how the concept of general intellect can be used to define not capitalist development but its sabotage, the struggle against this development’. With the implementation of a tiny, costly and conservative education market that looks like the near future of education in Britain, we will have to build these spaces from sheer necessity, starting with models like the free school, the school-in-internal-exile and the online community and working out our models from there according to conditions and our needs.

We can wish our way back to a former society of paternalist leftism and social partnership, of a series of deals between state, capital and organised labour in order better to manage our disaffection, and then, perhaps this time, a few more working class kids can get into an inadequate education system and rise through the ranks of management, if they play their cards right. It looks unlikely, though – capital has changed too fast. Or we can find a new, slightly different educational compromise with capital, but without organised labour, and most likely a worse, less secure deal. Or we can push forward, exploit the cracks to live up to the promises on our placards in a truer sense than even we knew then. To us, this isn’t even a choice- we must confront the world we are presented with, and aim for a world we want. FREE EDUCATION.

DSG EDITORIAL

Originally posted: February 11, 2011 at Deterritorial Support Group

Comments