A short history of the mass strike of miners in Nazi-occupied northern France from 27 May to 10 June. Despite heavy repression it won improvements to pay and conditions.

Background

In May 1940, Germany launched its offensive in the West.

After invading the Netherlands and Belgium, German troops marched into northern France.

The Nord-Pas-de-Calais area was attached to the military command in Brussels and its administration entrusted to the OFK 670 (Oberfeldkommandantur) Lille, led by General Niehoff.

After the armistice, these areas were declared a "forbidden zone", cut off from the rest of France by the Somme demarcation line.

The highly industrialised region was of key strategic interest to the Germans, who quickly moved to get production running again.

The mining companies, governed by a committee of the industry under supervision of the OFK, became auxiliaries of the occupying army, and the mines reopened on 15 June, 1940.

To increase yields, workdays were lengthened, breaks abolished and wages frozen, and production at pre-invasion levels was achieved by September.

Living standards for the miners were also hit by rationing and a rapidly growing black market, and famine peak during the winter of 1940-41.

The policy of collaboration of the Vichy government becomes increasingly resented by a population that feels abandoned to the Germans.

Working class discontent

As working and living conditions continued to deteriorate, discontent of the miners increased.

In the first months of the occupation, there were sporadic but repeated strikes and work stoppages, leading to a significant decline in yields.

In response, the Germans increased the length of the working day by half an hour from 1 January 1941, with no increase in wages. The decision enraged the miners, and communists and underground union activists took the opportunity to agitate amongst the workers - unions had been banned by the Vichy government.

The next day, the miners began a series of go-slows, carrying out work stoppages half an hour at the beginning or end of service.

Beginning at Pit 7 Escarpelle, near Douai, the movement spread to all the pits in Aniche and Escarpelle over the next two weeks.

Despite injunctions and measures taken by the French and German authorities, the movement continued until the arrest of nearly two hundred miners. Faced with a renewed strike in Escarpelle in March, the Germans sent in troops to occupy the pits.

On 1 May, International Workers Day, French tricolours and red flags appeared, and radical leaflets were circulated.

The following week the discontent spread to Belgium, where 100,000 steelworkers and miners walked out. Conditions were ripe for the underground organisers.

Towards a general strike

Finally, on 27 May there was the straw which broke the camel's back.

On top of the longer days, wage freezes and insufficient rations, the mining companies decided to impose payments by team, rather than individual, which would have meant lower wages for some miners.

Again beginning at Pit 7 in Dourges, the movement spread rapidly.

Workers prepare a list of demands calling for higher wages, better working conditions, improved supplies of butter, red meat, soap and more is presented to the employers.

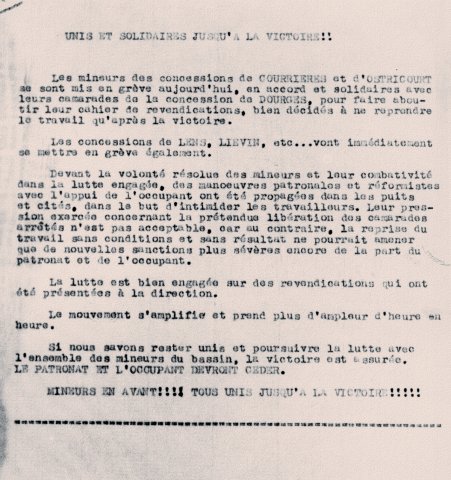

Leaflet produced by striking miners

By 29 May, the strike had spread to Courrières and Ostricourt, then to Carvin and Escarpelle the following day and Anzin the day after that.

In five days, the strike became general in the Nord and Pas-de-Calais regions and peaked 4-6 June, with over 100,000 striking from a workforce of 143,000.

Related industries including coking plants and power stations were affected, which then had a knock-on effect on the textile industry.

The movement was widely supported by women, who helped spread the strike. Everywhere they formed pickets, barring the entry of tanks and urging miners to strike.

They demonstrated outside oil company offices in Lievin, in Hénin-Liétard and Billy-Montigny to name but a few. And in some cases could only be disbursed by German troops using live ammunition.

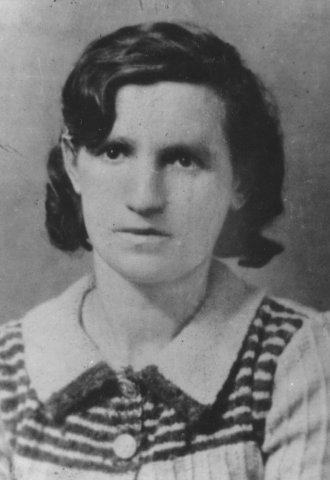

Émilienne Mopty (pictured) was one such woman. The wife of a miner, during the strike she became the key organiser of the women's demonstrations in Hénin-Liétard on May 29 and Billy-Montigny 4 June.

Forced into hiding, she was later arrested by the Gestapo and beheaded in Cologne on January 18, 1943.

Repression

Faced with this dire situation, the occupation authorities began to ramp up the repression.

The first arrests were made on 28 May from lists provided by the mining companies from reports made by engineers and mine guards.

However this was insufficient to halt the spread of the strike, so army reinforcements were brought in.

On June 3, General Niehoff ordered the putting up posters containing two notices: the first requiring miners to return to work, the second announcing the sentencing of eleven strikers to five years of forced labour and two women and two to three years of hard labour.

Still, the strike continued, so German troops occupied the pits. Public places, cafes and cinemas were all closed and gatherings of people banned. Payment of wages was suspended and ration cards were no longer distributed. Arrests multiplied.

Men and women were taken to the prisons of Loos, Bethune, Douai and Arras. The Kleber barracks in Lille and Valenciennes Vincent barracks were transformed into internment camps.

The toll was heavy: hundreds of people were arrested. 270 minus were deported in July in Germany; 130 died. Others were shot later in the year. Many of those who avoid arrest chose to go underground.

Michel Brulé (pictured), for example, was a miner at pit 7 Dourges, where he played a key role in initiating the strike, and he also committed numerous acts of sabotage. He was arrested and shot April 14, 1942 in Marquette-Lez-Lille.

End of the strike

The wave of terror and hunger took its toll on the miners, and they were forced to return to work on 10 June, having cost the German war machine 500,000 tonnes of coal in lost production.

However the authorities were forced to grant concessions: German authorities introduced a special service to bring additional food and workloads to the miners, and the Vichy government granted a general increase in wages on 17 June.

Source

La greve des mineurs du Nord-Pas-de-Calais, 27 mai-9 juin 1941 - retrieved 16/05/16

Comments