The following is the text of a paper delivered to the first biennial Wollongong History Conference hosted by the University of Wollongong in June, 2007. The theme for the conference was Memory, Heritage and Place: Wollongong’s Changing History.

The paper is based on part of my honours thesis completed in 2006, which involved interviewing people who were active in the Wollongong Out of Workers’ Union (WOW) during the 1980s (excerpts of two of those interviews can be found in Unity Volume 6, Number 1, 2006).

It was a powerful moment when, at the opening of a conference addressing memory and crisis, the keynote speaker (Julianne Schultz, author of Steel City Blues) was overcome with emotion when remembering parts of this cities turbulent past. It is important that we remember and acknowledge the pain and suffering that was created during the 1980s, and how for some, that pain and suffering continues to this day. Therefore, I would like to dedicate this paper to those who die, suffer and never recover, from the trauma of unemployment.

In Wollongong during the 1980s unemployment sky-rocketed as capitalist crisis brought about mass sackings and a huge rise in youth joblessness. As part of a significant fight-back by the labour movement in Wollongong against unemployment and its effects, unemployed people in the Illawarra formed the Wollongong Out of Workers’ Union commonly known as WOW. This paper will focus on the fightback by Wollongong workers and the unemployed against mass sackings, joblessness, poverty and austerity in the early 1980s. As well it will look at the activities of WOW and the historical processes of dispossession that the Union struggled against.

Wollongong has a long history of social activism, the most powerful and influential collective expression of which has been the labour movement. By the 1970s, after years of determined struggle, the workforce in the local steel and coal industries had been successfully unionised and gained relatively advanced wages and conditions. United in the militant South Coast Labour Council the region’s working class were a major obstacle to ‘market forces’. During the late 1970’s and through the 1980’s, the Illawarra felt the impact of major economic restructuring, technological change, deregulation and privatisation. Mass sackings, unemployment, poverty and social crisis gripped the region. The 1980s would see the closure of three quarters of the local mines and the eventual loss of around twenty thousand jobs in the steel industry. Already by 1983, when WOW was established, there were officially around 20,000 people registered as unemployed in Wollongong.

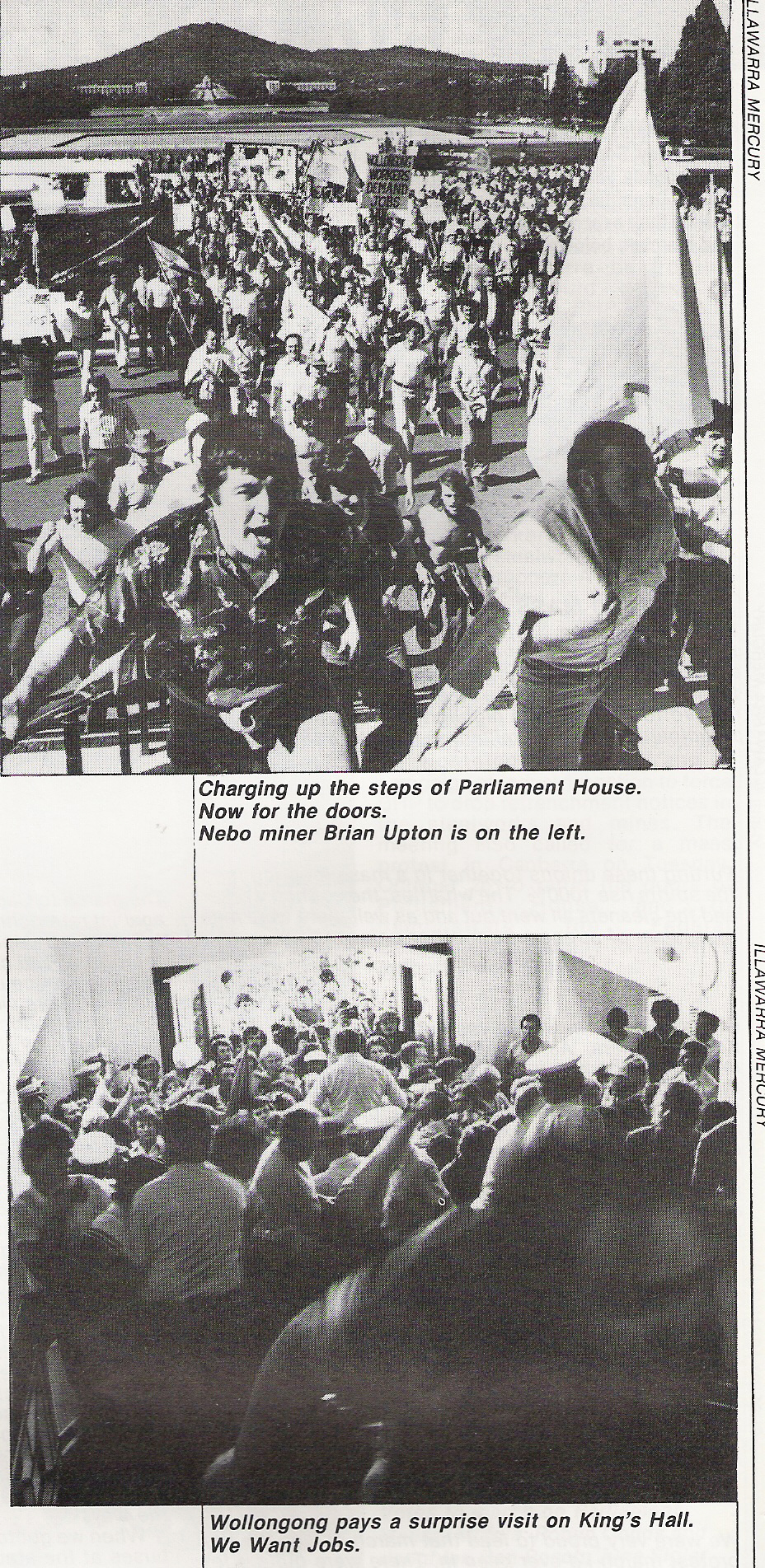

The city’s unemployment crisis brought out a collective response of militant struggle by many of its residents. In October 1982 the Kemira miners organised a sit-in strike to protest against their looming retrenchment, staying underground for 16 days. While they occupied the pit, a series of mass demonstrations filled the city’s streets, and workers packed the Wollongong Showground to vote overwhelmingly for strikes in the steelworks and the mines. This mass meeting also decided to march on Federal Parliament to protest against the Fraser Government’s lack of action to halt sackings. A special train was arranged to take thousands of workers from Wollongong to Canberra. When the workers arrived at Parliament, ALP leaders Hayden and Hawke were waiting to address them from a stage, and a flimsy barricade and a few police stood defending Parliament House. The workers swept past the stage, broke through the barricade, stormed up the steps of Parliament, and smashed their way through the doors, chanting ‘we want jobs’.

A month after the storming of Federal Parliament came the Right to Work March all the way from Wollongong to State Parliament. While initiated by another mass meeting of workers, many of those who marched to Sydney were young unemployed people. When they reached the city, the marchers were greeted by twenty thousand workers who had gone on strike in Sydney, Wollongong and Newcastle. The fight back against unemployment by Wollongong’s working class was so significant, that as leader of the Opposition, Bob Hawke, traveled here on the last day of his election campaign, promising a crowd of 10,000, gathered in the Dapto Showground, that he would save the steel industry within one hundred days of winning office. As the fight against sackings spread across the country, the Fraser Government was doomed and the Hawke Government was elected on a platform of ‘jobs, jobs, jobs’.

Before it was elected the Labour Party had cemented an ‘Accord’ with the Australian Council of Trade Unions. After the election of the Hawke Government, the nature of the Accord process was made evident in Wollongong with the implementation of the Steel Industry Plan announced in 1983. Here the Government and the ACTU accepted BHP’s long-term strategy, by supporting the provision of hundreds of millions of taxpayers’ dollars to the company, which was then invested in job-displacing technology. The Steel Industry Plan was rejected by local unions. But as the steelworks’ general manager, John Clark, pointed out “there is nothing like the contemplation of the hangman in the morning, to get people to co-operate”. While some would learn to cooperate with BHP’s plans, many of Wollongong’s unemployed soon became their own executioners, driven to suicide by the despair of joblessness.

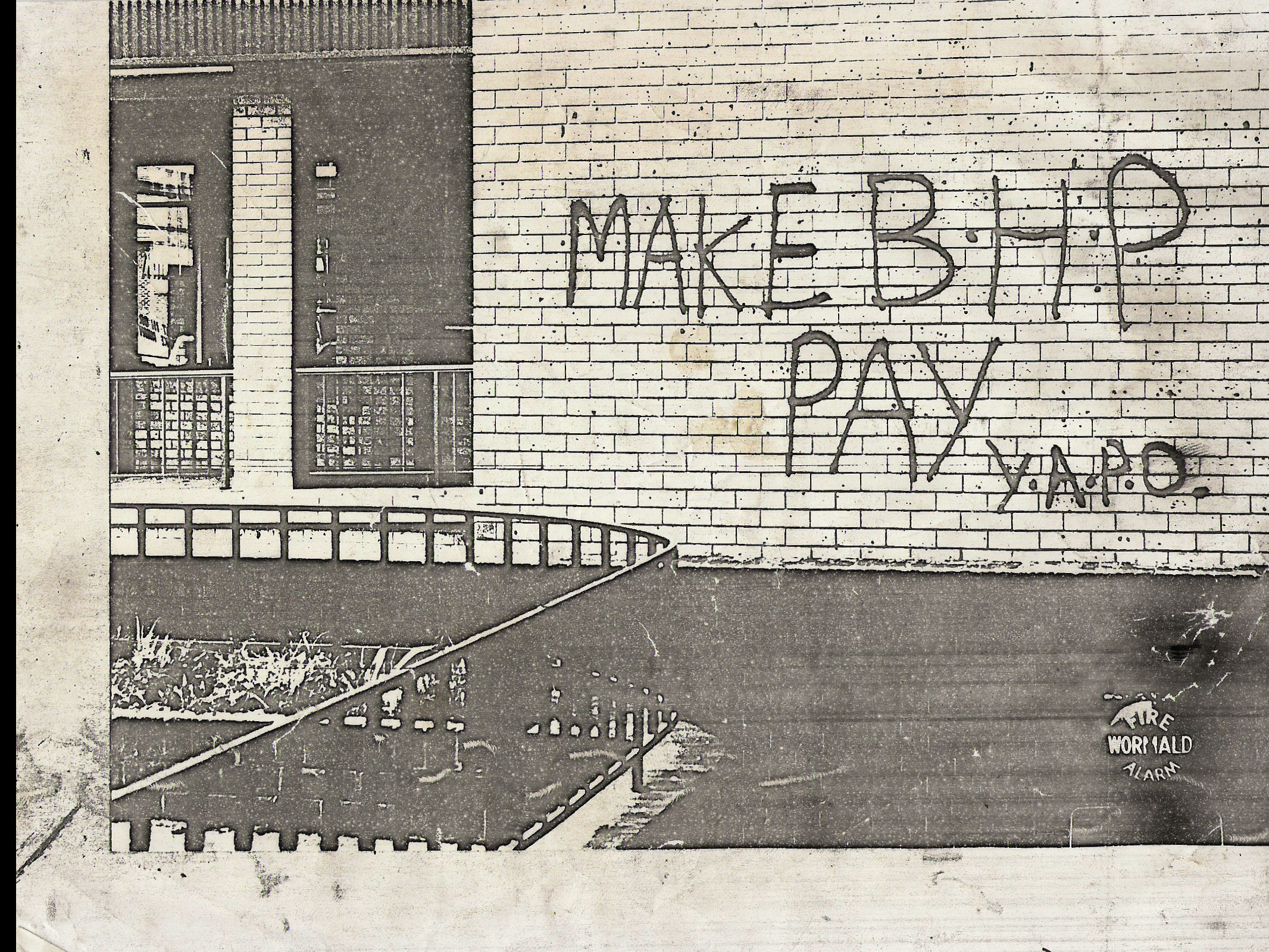

As news’ headlines around the nation proclaimed Wollongong’s agonising jobs’ crisis, local business interests launched a promotional campaign that named the area ‘The Leisure Coast’ and announced that the Illawarra was ‘alive and doing well’. In response, the young unemployed members of graffiti group YAPO (Young and Pissed Off) sprayed on the main symbol of the Leisure Coast, the North Beach International Hotel, “It’s unemployment not leisure”. While I haven’t got a picture of that graffiti, which featured on the front page of the Sydney Morning Herald, this is what YAPO sprayed outside the Wollongong Social Security office.

YAPO was one manifestation of a growing punk scene in Wollongong at that time. Around the same time, Redback Graphix, an anarchist/communist-inspired and punk-influenced poster collective was established in Wollongong. Redback produced a wide variety of brightly coloured posters for political and social struggles, including some for WOW, which were regularly plastered all around town. They also produced t-shirts, banners and other art works in support of workers’ struggles. In 1982 some of the people involved in Redback Graphix helped to produce the film Greetings from Wollongong. This punk-influenced feature film had ‘an unemployed all star cast’ of local youth. The film exposed the growing economic and social crisis of rising unemployment and the emergence of a ‘no future’ generation of young people. The award winning film was criticised by many of Wollongong’s political and business elite and the Wollongong City Council refused to allow the screening of the film in any council building.

As youth unemployment grew, so did punk culture. In Wollongong, punk’s focus on cultural rebellion and individual autonomy, mixed with the more overt political struggles that erupted during the early 80s. As punk historian Richard Boon explains: “The threat posed by early punk was that intelligent young working class people would throw off the shackles of oppression and step into history!” During the upsurge of struggle in 1982, many unemployed and soon-to-become unemployed workers did step into history, supporting the Kemira stay-in strike, the storming of Parliament and the Right to Work March. Some of these unemployed people were also active in Young and Pissed Off, the Community Youth Support Scheme or the Wollongong Unemployed People’s Movement. For various reasons none of these groups seemed able to provide unemployed people with their own organisation, solely controlled by unemployed people, an organisation that would help them unite and fight.

And so WOW was formed in 1983. Its constitution guaranteed unemployed people’s control over their own organization, by ensuring that only unemployed people could become full members with voting rights. As stated in its constitution WOW’s main aims were: to unite and organise the unemployed, to defend and extend their rights, to campaign for jobs and a living income and to foster closer ties with the trade union movement. Soon after being formed, WOW put together a Log of Claims as a political program for action, around which Wollongong’s unemployed could organise. The Log of Claims was a living document evolving as the union developed. It recognised that there were no jobs for most unemployed people and that it was not unemployed or employed workers but capitalism which was to blame for the unemployment crisis. The Log called for: the right to work to be a constitutional guarantee; permanent work under award wages and conditions; a continual shortening of the working week without loss of pay; and worker and community control over the use and implementation of new technology. Other claims included that the term ‘unemployment benefit’ be changed to ‘Minimum Living Wage Payment’ and that it be raised to the level of the minimum wage, and the conversion of military jobs to civilian jobs. The Log also included a wide variety of other claims covering tax, social security rights, essential services and more.

Having a comprehensive Log of Claims meant that WOW was constantly campaigning on a wide variety of issues and often allying with other community organisations, trade unions and political parties around shared concerns. Seeing the need for coordinated action by the unemployed on a national level, WOW also helped to establish, and became the Secretariat for, the National Union of Unemployed People (NUUP), linking unemployed unions from Melbourne, Sydney, Canberra, Adelaide, Perth, Newcastle, Hobart and Launceston. Together these unions drew up an agreed list of national campaign aims and coordinated action around an agreed political platform. Through the NUUP, links were also made with unemployed unions in Britain, New Zealand, Canada and South Africa.

Shortly after WOW was formed it was decided to go to Canberra to greet the incoming Hawke Government and present them with a log of claims on behalf of the unemployed. On the first day of the new Parliament WOW was there to greet them. It was against the law to camp on the lawns of Parliament, but WOW set up a camp anyway, and set about lobbying the new ministers. On their first two visits to Canberra WOW’s members were invited inside to meet Ministers and various MPs. A week before the Hawke government’s first budget, WOW members returned and held a hunger strike outside Parliament, to protest the level of the dole. On this trip, access to Parliament was barred. So a sit-in protest was staged on the Parliament steps. The police, with unexpected violence, broke up the demonstration. The following day, WOW members took their protest to the National Press Club, disrupting Treasurer Paul Keating’s speech, in front of a national TV audience.

Back in Wollongong, the Union began its ‘Steal, Sleepout or Starve” campaign, to highlight the fact that young unemployed people had to survive on $40 per week. In the middle of June, with icy westerly winds whipping down on the city, WOW members began a two week day and night vigil outside the Social Security offices in Market Street. The aim was to collect the signatures of all the unemployed in central Wollongong, on a petition demanding dole increases, and by sleeping out on the street, in the middle of winter, to highlight youth homelessness. When some of the WOW members taking part were hospitalized, with exposure, it was decided to break into and occupy one of the empty houses across the road. With community support, including that of the South Coast Labour Council, who put pressure on the police and the owner, this house became WOW’s offices, for the next six years. Here unemployed people could meet, organise and help support each other.

About twenty WOW members made the Market Street house their home, sharing a couple of rooms to sleep in. With a permanent base, WOW quickly established a drop in centre, soup kitchen and welfare rights centre. A layout and graphics workshop was set up in one room of the house, and the laundry was turned into a darkroom. A PA and portable recording studio were donated and used for community radio shows, theatre productions, conferences, meetings and concerts. From the house, WOW also produced its own free monthly newspaper, The Gong, and thousands of copies of each issue were widely distributed. Soon WOW’s membership grew into the hundreds.

To run various campaigns and organise protests, WOW established sub-committees, made up of interested members. The union’s welfare rights centre didn’t just rely on traditional advocacy, but also used a form of direct-action casework, staging militant group actions when problems remained unsolved. At various times this involved WOW members occupying the local Social Security offices, the local taxation department and even the national headquarters of the Labor Party in Canberra. WOW also played an active part in the local women’s, peace and environmental movements.

Two years after its formation, the union was featured on the ABC’s Four Corners program, as an example of how alienated and unemployed youth could break their social isolation, be ‘empowered’ and become a progressive social force. WOW had a fairly high and positive public profile, as indicated by the Four Corners program. Yet, for many, WOW was seen as a group of punks. And while not everyone involved in the union was into punk, many of the more active members were. For the union members interviewed, WOW’s punk culture was based on the idea of “doing it yourself” and a rejection of the way capitalist society operated.

As its name indicates, WOW members also saw themselves as workers and unionists, who had been dispossessed of work. WOW took part in, and supported, many trade union campaigns, working with unions, to help win a number of struggles, for the payment of award wages, for workers employed on short-term job schemes. The Union also took part in trade union pickets, and when deemed necessary, conducted its own sit-ins, occupations, pickets and demonstrations against corporations, such as BHP. But, faced with a growing neo-liberal offensive, some unions began to back-pedal on defending wages and conditions, as part of the general retreat of social democracy during this period. While WOW continued to campaign for ‘real jobs with real wages’, some unions began to support the creation of short-term jobs, paying below award wages, and with eroded working conditions.

In order for places like Wollongong to expand their economic base, ‘the market’ now demanded increased labour ‘flexibility’, the cutting of labour costs, more profits, increased management power and an undermining of the power of labour. To grease the wheels of the ‘new economy’, people socialised in a region dominated by relatively stable unionised work, advanced wages and conditions, and class consciousness, would have to be re-trained and re-educated. As mass unemployment and social breakdown grew, employers and governments created new ways of managing workers and the unemployed, often with the cooperation of concerned labour and community organisations. These new forms of organisation were specifically focused on social containment and control via varied training, retraining and temporary employment schemes. The new training and education programs not only prepared workers for new forms of work but often operated as short term casual non-unionised workplaces themselves. Many unions keen to be doing something about unemployment cooperated with short-term job creation and ‘on the job’ training schemes turning a blind eye to the low wages, lack of decent working conditions, precariousness and increased power for employers. The legacy of mass participation in these schemes has been the creation of a new workforce conditioned to expect short-term or casual jobs, with poor conditions and low pay.

The deepening of the Accord process, led to increasing tension and divisions between WOW and many of the labour organisations which had previously supported the union. Unemployed people were excluded from the Accord process yet were expected to support a strategy that would result in cuts in real wages, attacks on the social wage, and continuing sackings. As unemployed unions continued to resist the Accord’s corporatist strategy, they were increasingly deserted by sections of their previous support base. As one ex-WOW member, who is now a trade union secretary, explained when being interviewed, “WOW was an organisation where class struggle and the concept of the class struggle as a motor for change in society developed as it got older. Whereas in that period the trade unions were winding back in terms of class struggle”.

At the same time, the Australian Security Intelligence Organisation (ASIO) decided to classify people trying to help organise the unemployed, as subversives. As trade union power and support for the organised unemployed receded, the federal government began a crackdown on unemployed unions. This included Federal police raids on the Launceston Unemployed Workers’ Union. For WOW, the crackdown involved continual harassment of union members by the Department of Social Security. In 1987, the government introduced an activities test for the unemployed, which was used to cut the benefits of unemployed people attending protests and those active in ‘political’ organisations, since they were deemed not to be ‘actively looking for work’. Faced with growing attacks from the state and withering support from the labour movement WOW disbanded in 1989.

A year later, Wollongong’s Lord Mayor, Frank Arkell, proclaimed that Wollongong was now vital, progressive and vigorously developing, providing “boundless opportunity and economic growth”. Yet, when the ABC’s Four Corners program revisited the Illawarra, the following year, journalist Chris Masters told the local media he was shocked by the lives of the regions poor. When his show went to air, it was titled The Callous Country, and detailed the continuing mass poverty and unemployment of the region, and how the screen pulled down over the unemployed, had been very effective.

Today, unemployment in Wollongong is still higher than the national average, and nearly one in every two young people are out of work. The average income of Wollongong workers is now significantly less than the NSW average and the lack of local jobs sees twenty five percent of the workforce commute to Sydney each day for work. Many of Wollongong’s unemployed remain economically and socially marginalised, condemned to a life of poverty and insecurity, consigned to the worst public housing estates and subjected to police and Centrelink harassment. While the constant push for development and job creation continues to show little regard for quality of employment, regional corporatism continues to re-brand the region as a commodity and its residents as a largely tamed workforce.

While many of the houses in Central Wollongong, like much of the cities history, have now been demolished, the WOW house in Market Street is still there, dwarfed by the businesses on either side. Originally built in the Great Depression of the 1930s, by local funeral director, Mr. Parsons, it links Wollongong’s two depressions with today. A small almost forgotten part of Wollongong, shadowed by the glittering new businesses that surround, dominate and help to conceal it. But, while the history of Wollongong’s unemployed people’s struggles tends to remain hidden, the memories and affects of those struggles live on, in the hearts, minds and continuing struggles of those who took part and are connected to them.

Comments