Issue 22 of Anti-Fascist Action's Fighting Talk magazine.

Contents

- In The Area - AFA news from around the UK

- Levelling The Score - football

- Flabby Pacifism - review of Dave Renton's "Fascism: Theory and Practice"

- Behind Enemy Lines - update on fascist organisations

- Between The Sheets - mainstream coverage of fascism

- AFA and the media

- Letters

- Report from Red Antifa, Berlin

- Anti-Fascist History - Birmiingham

- The Beat Goes On - music

Attachments

Anti-Fascist Action's review of the Socialist Worker Party member Dave Renton's "Fascism - Theory and Practice" published by Pluto Press in 1999. The review appeared in issue 22 of Fighting Talk magazine.

At a time when the Far Right have lust polled over 11 million votes in the European elections in June and the BNP more than doubled their vote in a number of parts of Britain, this book clearly shows the failure of the Socialist Workers Party/Anti-Nazi League (SWP/ANL) to come to terms with modern day fascism.

Much of the book is an academic analysis of what other writers and historians have said on the subject since the 1920s and is written in such a way as to be of little use to active anti-fascists, but when the author (a member of the SWP/ANL) deals with the current period the weakness of the ANL strategy is fully exposed.

It goes without saying that Anti-Fascist Action is written out of history, and gross exaggeration is commonplace, but his comments on the British National Party's election victory on the Isle of Dogs (1993) draws attention to the flawed analysis. He scoffs at the BNP's anticipation of further electoral success, based on the fact that Beackon lost his seat eight months later, without saying anything on the significance of this episode.

Firstly, despite considerable anti-fascist propaganda, Beackon's election showed the limitations of just being 'anti' and the need to put forward a positive alternative; this led to AFA developing the Filling The Vacuum (FTV) strategy.

Secondly, there is no mention of the Left's support for Labour (who won the seat from the BNP) when it was local disillusion with the Labour Council that caused the problem in the first place. This put the SWP/ANL in the position of defending the status quo, of anti-fascists being hostile to the working class desire for change.

Renton writes that "the revival of the Labour Party as an electoral force undermined the BNP and made it harder for (them) to pose as a viable alternative.” In fact it is precisely because of the election of Labour, both locally and nationally, armed with its anti-working class agenda that, in the absence of a genuine working class alternative, allows the BNP to pose as a very "viable alternative".

As he states later on, "if anti-fascists fail to use the language of class against capital, then they will not persuade working class or lower middle class people who are genuinely angry about the world they live in."

So quite how the SWP/ANL manage to resolve the contradiction between their support for Labour and their role as a “revolutionary socialist party fighting for the interests of the working class” remains a puzzle; and by all accounts is starting to split the party.

According to Renton “Beackon lost his seat in May 1994 and since then the BNP have gone into decline." This is absurd. Not only do the SWP/ANL ignore the writing on the wall after the Isle of Dogs election with regards to anti-fascist strategy, but basic reality is denied. Since 1994 the BNP have adopted the Euro-Nationalist strategy, so successful elsewhere, and have steadily built the necessary infrastructure to sustain it.

Even the most basic knowledge of fascism in Britain would reveal that the BNP have grown in numbers, equipment, technical expertise, and the ability to exploit the media. On what basis can you claim the BNP has "gone into decline"?

Further evidence that the SWP/ANL strategy is built on sand is Renton's assertion that despite the growth of the Far Right, there is also a "rebirth of radical forces on the Left''. The evidence in Britain is that the Left is in terminal decline. While it is obviously true “that it would be wrong to see the continuing success of fascism as inevitable" the situation clearly won't improve if the Left continues to follow strategies that have failed so spectacularly for the last 30 years. The Socialist Labour Party, the main 'left of Labour' rival to the fascists in the Euro-elections were beaten in 7 out of 10 regions where they competed. Despite the BNP's recent attempts to attract middle class support, their main base of support is in white working class areas. Until the Left start to represent the needs of these communities the fascists will continue to grow.

The reason Fighting Talk is reviewing this book in some detail is because the "final section proposes a strategy by which it may be possible to drive fascism, once again, beyond the pale". So, what is this strategy?

Renton starts off by arguing that the best way to defeat fascism is through the United Front - a ''strategy of working class unity". When Trotsky developed the theory in the 1930s he argued that the Socialist and Communist parties. should unite to beat the fascists; in those days both parties were mass working class parties.

Nowadays Labour (the equivalent of European Socialist or Social Democratic parties) is not a mass party but a middle class electoral machine, and their standing in working class communities is well illustrated by the fact that they lost all their council seats in the former Labour stronghold of the Rhondda Valley in May's council elections. Unity with Labour only serves lo discredit anti-fascists and helps the BNP appear as a radical alternative.

Similarly the Communist Party has all but disappeared and certainly the SWP are in no position to present themselves as a mass working class party. So the two central components of the United Front strategy, mass working class reformist and revolutionary parties, are missing. Hardly an auspicious start!

And it’s worth pointing out that as far back as April 1990, when the BNP's Rights For Whites campaign was launched, AFA wrote to the SWP inviting them to "join with us to fight fascism". Not only did they not reply, but two years later; having made no effort to fill the political vacuum created by AFA, they relaunched the ANL to try (unsuccessfully} to duplicate the work AFA was already doing. So much for unity.

As for his claim that "the ANL was established as an orthodox United Front”, not only have we shown that the necessary components are missing, but the ANL's cooperation with Searchlight and the Labour Party, who work closely with the police and intelligence agencies, in fact makes it a Popular Front in Marxist definition (i.e. an alliance with 'anti-fascist’ sections of the establishment) - or perhaps better described as an Unpopular Front!

Renton then goes on to say that "where fascism is already seeking to control the streets, the most important thing to do is to confront the fascists". But when SWP paper sales were being targeted and beaten off the streets all across the country in the early 1990s, the official response was to deny the attacks were taking place.

At a time when the BNP leadership was seriously concerned about the damage that AFA was doing to them, these attacks on the SWP were vital morale boosters for a disillusioned membership. Due to AFA implementing a strategy that the SWP/ANL promote but refuse to act on, the BNP have withdrawn from street activities which is why AFA has developed new strategies to keep the pressure on the fascists. The lack of discussion about this important change of strategy, evident since 1994, is another weakness.

Presumably the absence of any BNP marches and rallies allows the ill-informed or superficial anti-fascist to believe they have gone away, which coupled with a lack of involvement with working class communities leads to complacency. He tells us that “where fascist groups are small, isolated and squabbling, it would be a mistake for Marxists, democrats, or socialists to devote their entire energy to hounding down the few remaining fascists”.

Since 1980 the SWP have often tried to reduce militant anti-fascism to some form of gang warfare, having expelled their own squads, and while they deflected criticism of their abandonment of anti-fascism during the 80s by using this sort of smear, it takes on a new meaning in the present situation where the Far Right are growing, but largely ‘invisible'. Just because Searchlight have told them the BNP are in decline doesn't mean it’s true. And in yet another contradictory move, it is in fact the ANL who insist on mobilising against the "few remaining fascists" of the dead-in-the-water National Front while failing to develop a strategy against the real threat posed by the BNP.

This failure to address the political problems facing anti-fascists is matched by their inability to deal with the physical side of the struggle. Masters of the militant slogan (‘Smash the BNP!', 'By Any Means Necessary!' etc.) their confusion is complete when contemplating anything more demanding than lollipop-waving.

Renton advocates a militant No Platform position and urges “anti-fascists to go into areas where fascists seem strongest” but then argues that any “physical confrontation… must be primarily non-violent”. The contradiction is glaringly obvious, and any of the young students sent into the BNP ambush on the ANL's first ever mobilisation (east London 1992) could testify to the serious injuries that are inflicted when security is ignored. It is no consolation for him to add "where fascism poses a significant threat, anti-fascists may have to defend themselves", because if this isn't organised it won't happen.

Significantly, when he describes the success of the original ANL in the 1970s he mentions the leaflets, the badges and the carnivals but not the squads. The success of the ANL was the combination of physical and political opposition, one could not have succeeded without the other. Not only were the squads used to disrupt fascist marches and meetings, sometimes with devastating effect, but when left-wing paper sales got attacked, fascist sales were targeted in retaliation to dissuade the NF from this course of action. And it worked.

In a bad attack of liberalism Renton says “for anti-fascists, violence is not part of their world view" and dismisses militants as “professional anti-fascists". The whole history of anti-fascism, in this country and everywhere else, has involved the use of force - so why should 'revolutionaries' be so keen to distance themselves from it?

Should we be ashamed of the Italian Arditi Del Populo, the German Red Front Fighters League or even the International Brigades? Is it because the middle classes see violence as 'right-wing', are they scared of upsetting their friends in the Labour Party (Peter Hain MP is the Chair), or do they simply not have the members with the stomach for the fight?

Whatever the answer, it has always been a dishonest position, posing 'mass action' against organised physical opposition, when in fact they are complementary tactics. A similar argument was put forward by the leadership of the German Communist Party in the struggle for power with Hitler's Nazis, leading to a militant from the Communist Youth to comment, ''we don't care for the idea that if we are murdered by SA (Brownshirt) men, a small part of the working class will carry out a half hour protest, which only makes the Nazis laugh for having got off so lightly".

And even Trotsky, the theoretical godfather of the SWP's anti-fascism, insisted that “fighting squads must be created". He stressed that “nothing increases the insolence of the fascists so much as 'flabby pacifism' on the part of the workers organisations" and denounced the "political cowardice" of those who argue "we need mass self-defence and not the militia. But without organised combat detachments, the most heroic masses will be smashed bit by bit by the fascist gangs".

Apart from the obvious necessity of being able to defend your own activities, at present the need for the use of physical force against fascists is minimal. While this may only be temporary, it does call into question the No Platform strategy. Again Renton is found lacking in terms of understanding the current situation.

In the 1970s No Platform was an achievable objective, but in the late 90s, with the BNP withdrawing from public activities, it becomes less relevant. Even when the NF have held an occasional march, never numbering more than 50, the size of the police operation against anti-fascists has prevented any effective confrontation. And despite tampering with the numbers of candidates required to get TV broadcasts and the increase in the cost of standing those candidates, designed to exclude the BNP, the fascists have succeeded in meeting the new targets and gaining a platform. The media are prepared to discuss Euro-Nationalism quite favourably at times, but even so the BNP are developing their use of the Internet and video to ensure their propaganda can't be banned.

His coverage of European events shows the same gap between theory and reality, suggesting mass protests have stopped the growth of fascism. Activists on the ground have a very different view, leading an experienced militant from Hanover to comment “it is bullshit and this Dave Renton knows nothing about fascists and anti-fascists in Germany". He claims that the Far Right are very weak, an absurd assessment, particularly in light of the Deutsche Volks Union entering regional government in Saxony-Anhalt earlier this year, and now Brandenburg as well.

Even if Renton's motive for writing this book was to challenge the views of right-wing historians, it doesn't alter the fact that it proposes a strategy that doesn't work. The SWP/ANL have made no analysis of the changes in British fascist strategy and are sticking to a blueprint drawn up by Trotsky in the 1930s (but never implemented), which largely worked in the 1970s, but is redundant today. His closing comment is that fascism will only be finally defeated when capitalism is overthrown, but with an anti-fascist strategy that makes no impact on the fascists, what chance have they got of overthrowing the capitalist State?

AFA verdict: This is not anti-fascism.

Comments

An article about the history of anti-fascism in Birmingham and the West Midlands from Anti-Fascist Action's Fighting Talk magazine (issue 22, October 1999)

The West Midlands, heavily populated and industrialised, has long been an important target of the Far Right. In the pre-war years the British Union of Fascists (BUF) attempted to establish themselves in Birmingham. After the war immigration from Asia and the Caribbean became the primary focal point for fascist groups, especially as the boom turned into decline and working class areas took the brunt of the State's divisive social and economic policies.

The effects felt in the communities of Birmingham and the Black Country were acute and were inherited by Anti-Fascist Action from its inception years later. It’s against this backdrop that we investigate a few examples of the opposition to fascism that came from within the same class the Far Right sought to dominate - a tradition that continues to this day. The BUF was launched by ex-Birmingham Labour MP Oswald Mosley in 1932, and soon after opened up its first offices in Stratford Rd, south Birmingham. The BUF quickly gained much interest and support from sections of the media and the establishment. Hitler and Mussolini were being keenly observed and admired by influential figures in the British status quo, hence the growth of the BUF to a viable organisation of government was not inconceivable.

Mosley made an attempt at a breakthrough in Birmingham a year or so later, when the BUF organised a rally in the Rag Market. The meeting was plagued by scenes of disorder, as anti-fascists fought with BUF stewards. Mosley returned to the Birmingham area the following January, when the BUF hosted a large rally at Bingley Hall. Clearly conscious of the Rag Market rout Mosley elected to place no less than 2,000 Blackshirt stewards on duty for the event, drafted in from across the Midlands, Liverpool, Manchester and London. 5,000 people attended in all, but the heavy security presence prevented any serious disorder within the meeting. Outside though there were a number of clashes between anti-fascists and Blackshirts as Mosley left, quelled only by large numbers of police.

The right-wing press reported on Mosley's keynote Bingley speech in favourable detail. Birmingham papers the Mail and Gazette endorsed Mosley, printing what amounted to lengthy policy statements on behalf of the BUF, praising the general organisation of the rally, and presenting overt endorsement of much of what was said from the platform.

Despite considerable press sympathy, including the newspaper Baron Lord Rothermere, Mosley's movement was still struggling to strike a chord with the Midlands working class. Hence in the summer of 1934 G.K. Chesterton was drafted to Birmingham as officer-in-charge of Warwickshire and Staffordshire BUF, in an attempt to shape up and reorganise the local movement.

In May 1935 there was another large Mosley rally at Birmingham town hall. Proceedings were disrupted throughout by crowds of anti-fascists involved in hand to hand clashes with Blackshirt stewards all around the hall. Arthur Mills, BUF organiser for Birmingham, was amongst the injured. Mosley told the press that the disturbance was the most serious he had seen for two years, except that at Olympia. “Members of our movement were violently assaulted by reds in the audience”, he said, and that anti-fascists had come organised for violence. At ten o'clock the meeting was closed down and Mosley made off, flanked by his Blackshirt minders.

Attentions turned to Spain in 1936, and anti-fascists rallied in Birmingham's Bull Ring. 71 volunteers from the industrial Midlands joined up to the international Brigades to fight Franco. Some never came back and many more were injured. Colin Bradsworth was a doctor from Birmingham who became battalion medical officer. His bravery during some of the worst fighting at Jarama was exemplary - ferrying the injured and dying under heavy gunfire until he was shot himself. He still continued dressing and treating the injured, despite his own wounds.

As concern about fascism in Europe grew, there were a number of demonstrations at the town hall, and also in Neville Chamberlain's Edgbaston constituency, against what were seen as the Liberal government's pro-fascist policies. In February 1937 a socialist 'United Front' was set up in Birmingham to promote the defence of working class interests against fascism at home and abroad. The following year Chamberlain, in an unconvincing appeasement speech at Birmingham town hall, vowed to “eat his hat” it war broke out!

During 1940 the BUF tried to set up a new headquarters and bookshop in Grove Lane, Handsworth. In less than a week local women forced its closure - threatening that the shop would be smashed, as would the local organiser. The BUF in Birmingham had become a spent force. After the war there began a huge influx of immigrant labour to Birmingham and the Black Country. Hence during the 50's and 60's racial conflict became the catalyst for resurgent fascist activity. Successive governments manipulated the economy, declared war on the unions and gradually wound much of the traditional industry down.

The result of this overall labour and social policy brought hardship, unemployment and urban decay - and the immigrants who were initially shipped in to do much of the menial low paid work were now resented by many of the white working class, spurred on by the institutionalised racists of the middle classes and the establishment. Even the unions played their part - in the late 50's, for example, Birmingham TGWU leadership objected to immigrant bus workers, on the grounds that white women members would not be safe.

Racial violence in the Black Country was a feature throughout this period. In Dudley the mid-50's were marred by three consecutive nights of some of the worst anti-immigrant violence the Midlands has ever seen. 'Paki bashing' became a sport amongst many white gangs in Wolverhampton, activities further 'legitimised' when Wolverhampton MP Enoch Powell gave his 'rivers of blood' speech in Walsall.

Smethwick too became a national focus during the early 60's, where colour-bars were openly enforced in pubs, clubs and even barbers' shops - leading to the Tories crushing Labour in the 1964 council elections under the slogan “If you want a nigger for a neighbour, vote Labour”, Birmingham Immigration Control Association and the Racial Preservation Society threw all their resources at the areas of Handsworth, Smethwick and West Bromwich, with fascists coming from far afield to whip up racial conflict. Race was rapidly overtaking class as a primary grassroots political focus. The stage was being set for the National Front's forthcoming campaigns right across the West Midlands.

By the mid-70's the National Front were successfully raising their electoral profile. One union had responded to a 1974 appeal to oppose the NF stating:

“Our organisation is not here to protect coloured people but to protect whites from competition for housing and jobs.”

The NF also used the IRA pub bombings of the same year to stir up a wave of animosity and attacks against Birmingham's large Irish community, further bolstering their potential support. For the next five or six years the NF would stand candidates in virtually every election contested in the West Midlands, polling some 8,000 votes in the 1977 County elections in Wolverhampton town alone.

In 1976, 3,000 took part in a counter-demonstration against the NF in Stetchford. The march was called by Asian and black organisations and set out to remain in the immediate area where 1,000 NF were marching. The Trades Council insisted on calling their own march of 300 for the same day which was to be a 'show of strength', in the city centre, safely out of way of the NF. The Labour Party opposed any counter-demonstration against the Front. The gravity of the situation would only be remedied by more urgent tactics.

The following August, three days after heavy violence was inflicted on the National Front at Lewisham, they had another taste of 'red terror' at a by-election meeting due to be addressed by John Tyndall in Birmingham's Ladywood constituency. 120 fascists were besieged in Boulton Road school by a mob of 5-600 anti-fascists, armed with bricks, sticks and bottles, and fierce fighting erupted.

The police came under heavy sustained attack as they did their utmost to protect the NF. Dozens of police were injured. As the meeting closed a crowd of about 300 anti-fascists smashed a police roadblock, and attacked Thornhill Road police station in an attempt to free anti-fascist prisoners. The Times report reflected the new militancy of the protesters:

"A police bus bringing reinforcements from the meeting more than a mile away ran a gauntlet of missiles and had all its windows shattered. Several officers, including a policewoman, were helped out with blood streaming from their faces.”

The NF still took third place out of ten, but Ladywood marked a turning point for all sides.

During the election campaign three Labour Party headquarters had their windows broken, owing to their election agent, Peter Marriner, being forced to resign over allegations that he had previously had extreme right-wing associations (Marriner resurfaced three years later attacking a Bloody Sunday commemoration in Birmingham, as regional organiser for the British Movement!).

The National Front's by-election headquarters in Broad St. were also attacked and ransacked by anti-fascists a few days before the election. At the count there was further trouble, culminating in Anthony Reed Herbert, the NF candidate, getting punched square in the face and having his glasses broken by Raghib Ahsan, the Socialist Unity candidate. Ahsan and other anti-fascists were ejected by police, but he later told the press “I did it and I am proud that I did it. I would do it again if I saw him.”

Reed Herbert announced his resignation from politics less than a week later, unnerved by increasing violence and a glut of telephone and written threats. The jewel in the crown that week though was a shotgun attack on the family antique shop in the East Midlands, in which his brother escaped a bullet in the head by no more than an inch or two. Reed Herbert, like many other Front officials across the country at that time, could not cope with being both outmanoeuvred and out-terrorised by the new strain of uncompromising opposition.

In February 1978 the Young National Front returned to march through the Digbeth area of the city, amidst more scenes of militancy from anti-fascists. Some 400 NF gathered at Digbeth Civic Hall, countered by around 7,000 anti-fascists.

The Birmingham Post described the initial outbreaks of violence:

“The main body moved right, but a group of about 50 realised there was no police force preventing them from moving towards Digbeth. Youths aged between 13 and 18, black and white, many wearing football scarves, ran to a demolition site in Floodgate Street to collect bricks and stones. Bricks, bottles, spark plugs, sticks and broken paving slabs rained down on the police...”

Riots broke out that cost the city in the region of £1,000,000, and although the NF meeting went ahead the siege of Digbeth was another bitter blow to the NF. The Lord Mayor of Birmingham called for the reintroduction of the birch in the aftermath of the rioting. The Trades Council, who had helped organise the counter-demonstration, attempted to distance themselves from the more militant elements, as they did at Stetchford nearly two years earlier. Ironically they again distanced themselves along racial lines, telling the Birmingham Post:

“There were several hundred people. including black and Asian youths, who broke away and became involved in a confrontation situation with the police.”

The inference was that violence was 'beneath' the Left, and the presence of black youth had inflamed the situation. Not surprising then that 18 months previously Bill Jarvis, then head of Birmingham Trades Council, had capitulated to the 'race not class' lobby by calling for a temporary halt to immigration.

At the end of April 1979, the NF held another pre-election rally at Cronehills School, West Bromwich, an area where they'd enjoyed good electoral support in the early seventies. There was fighting inside the venue, between the NF and 150 or so opponents, broken up by a hundred police forcibly entering the hall. Outside youths split away from the Anti-Nazi League march and clashed with some of the 2,000 police present on West Bromwich ringway. Searchlight man Dave Roberts, in the guise of ANL assistant secretary, was on hand to blame the violence on the NF and rogue elements. He commended the police on doing “a very good job”.

The Tories stole the NF's anti-immigration thunder at the '79 election - but fascism didn't entirely disappear. Irish events were systematically attacked throughout the 80's, which in part led to the formation of Midlands AFA as the decade drew to a close.

Not so well documented is the significant role of youth culture - both in aiding the growth of fascism and combating it. There were many clashes at punk and ska gigs, as well as between street gangs. The growing influence and strength of black and Asian youth on the streets played a vital role in helping to stem the tide, outlined in this recollection:

“Around the Black Country there were a number of clashes between skinhead NE supporters and the opposing Rude Boy gangs, which were racially mixed.... The NF came a couple of times to the school distributing 'Bulldog', their youth magazine, to kids on their way home.

The NF made out they were for the whites, but what I ask myself now is who was for the working class? My elder brother became infatuated with the Front. Only a year later he'd buy Socialist Worker and other left-wing papers outside work - like everyone he was looking for a voice, an outlet, not that he would've found much joy there either but, I can see how he thought now in hindsight.

A sister of mine also fancied herself as a skinhead girl, though not in the slightest bit racist, more to do with the kudos of being associated with lads who were seen to be something. It was almost like a Robin Hood scenario, being seen to stand up and reject the establishment - a sense of identity. even if it manifested itself in a reactionary way, such as supporting the NF. But circumstances gelled to provide the NF with support from the worst off.

National Front 'suits' apparently came to the pub at the top of our road to address a NF meeting, comprised mainly of the teenage ‘Oakham Skins', who had by now adopted a reputation for violence, irrespective of the fact that many of the black kids and the Rude Boy elements, including the Asian contingent, were fast becoming the hardest and most feared 'firms' in the area. Further afield, a mile or so away in Tipton, I was told how the NF had suffered heavy casualties when a gang of Brumrnie punks had teamed up with Tipton residents to smash an NF meeting.

Yet the NF's ability to maintain a fearsome reputation was unabated. From the Oakham meeting a group of skinheads left, equipped themselves and burnt down an Asian shop in nearby Netherton, killing one family member. Some of the perpetrators would've been off our estate. A family friend at the bottom end of our road went out with a black bloke and woke up one morning to find her dad's house daubed from top to bottom with painted swastikas and NF graffiti.

The Indian shop at the top of a relative's street in south Birmingham was attacked. Racist street attacks, particularly towards the more vulnerable, seemed commonplace. Retaliation did take place though, with a fair degree of organisation. Ultimately I suppose it came down to who could instil the most fear and get the situation under their control. Looking back now the fascist skins lost it physically, the climate was such that they couldn't operate.”

The NF never really recovered, and on occasions since when they've tried AFA have often been on hand to ensure it stayed that way. Part of a proud tradition of working class militant anti-fascism that continues to the present day. To those who sneer about AFA 'thuggery' and 'squadism' - take a look at those you revere in history, and tell us why it's suddenly different now. “At which point in this continuous tradition of confrontation do you draw the line and say physical opposition is no longer acceptable?”

A booklet A History of Fascism And Anti-Fascism In Birmingham and the Black Country will be available from the WM AFA PO Box in September, price £2.00.

Comments

There is a good (but watermarked) image of the aftermath of the riot at the 1931 town hall meeting here:

https://www.gettyimages.co.uk/detail/news-photo/riot-at-a-new-party-meeting-in-birmingham-held-by-sir-news-photo/138602796

UNITED KINGDOM - MARCH 15: Riot at a New Party meeting in Birmingham held by Sir Oswald Mosley, 1931 (Photo by National Media Museum/Daily Herald Archive/SSPL/Getty Images)

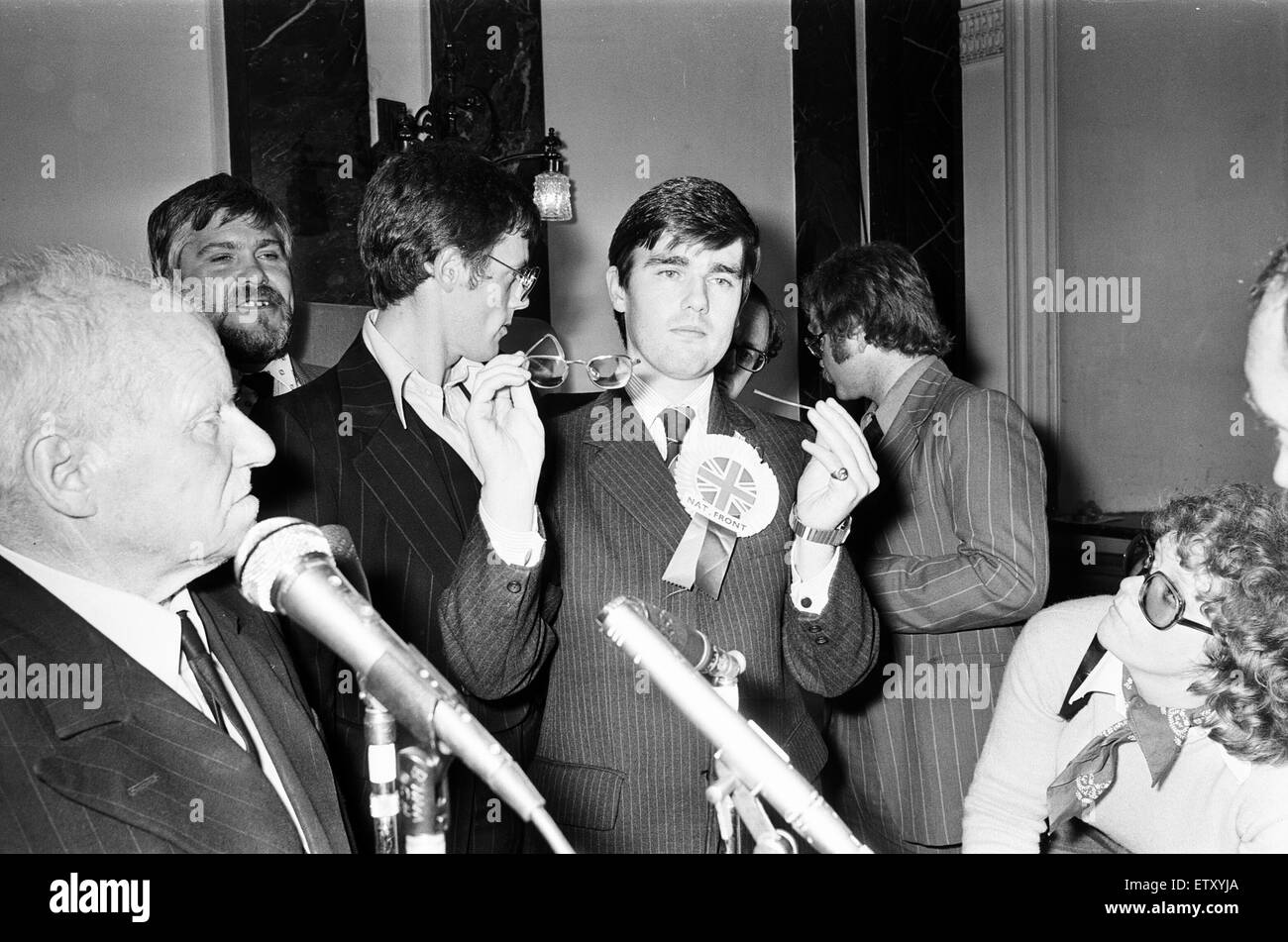

That's a good one. When I started reading your post I thought the picture it was gonna be this one of Anthony Reed Herbert holding his broken glasses after getting them smashed at the Ladywood election count mentioned above:

Comments

Fozzie, are you taking

Fozzie, are you taking requests in terms of articles you're pulling out of the PDFs and sticking on the site as separate articles? Coz I'd really like to see the anti-fascist history of Birmingham piece from this issue as a stand-alone article if you are!

Sure!

Sure!