Philosopher David Buller tackles the evidential claims of primary exponents of Evolutionary Psychology. Buller challenges the paradigm and research programme of Evolutionary Psychology, rather than the notion of a psychology informed by evolution.

by David J. Buller, (Skeptic vol.12, no.1)

In nearly every newspaper or magazine these days you can find evolutionary explanations for a variety of human behaviors — for what we seek in mates, why we are sometimes unfaithful, why we love our children (but not our stepchildren), why men and women differ, and even why husbands kill their wives. All of these explanations are offered in the name of evolutionary psychology. But what is evolutionary psychology?

There are actually two different answers to this question, and it is useful to clearly distinguish them. On the one hand, many behavioral scientists define evolutionary psychology simply as “the evolutionary study of mind and behavior.”[1]So conceived, evolutionary psychology is a field of inquiry, akin to mechanics, which is defined not by any specific theories about human psychology, but by the questions it investigates. And these questions cover a broad spectrum. Why do males in some hunter-gatherer populations hunt, which offers highly variable caloric returns, when they could reliably provide their families with equivalent calories by gathering? Why do women in some hunter-gatherer populations wait an average of four years between pregnancies? What evolutionary forces drove cortical expansion in humans? How and why did altruism, or language, evolve?

On the other hand, several prominent and influential behavioral scientists — led on the popular front by Steven Pinker (The Blank Slate) and David Buss (The Evolution of Desire and The Murderer Next Door) and on the academic front by Leda Cosmides and John Tooby (The Adapted Mind) — define evolutionary psychology as a specific set of doctrines concerning the evolutionary history and current nature of the human mind. In this sense, evolutionary psychology as a field of inquiry has been elevated by its practitioners to an all encompassing paradigm of Evolutionary Psychology (EP).

A defining doctrine of EP is that the human mind is massively modular, containing “hundreds or thousands” of “special-purpose minicomputers” called “modules,” each of which evolved during the Pleistocene to solve a problem of survival or reproduction faced by our hunter-gatherer ancestors.[2] Endowed with substantial innate knowledge, yet a very narrow range of expertise, each module is dedicated exclusively to solving a single problem — for example, detecting cheaters in social exchanges. A second defining doctrine of EP is that our minds remain adapted to a Pleistocene hunter-gatherer lifestyle — that, psychologically, we are living fossils of our Stone Age ancestors.[3] Accordingly, the evolved nature of the human mind is allegedly discoverable by “reverse engineering” the mind from the vantage of our Pleistocene past — figuring out the adaptive problems our ancestors faced and then hypothesizing the modules that evolved to solve them.[4]

Despite being an ardent fan of evolutionary psychology, I’m deeply skeptical about the Evolutionary Psychology paradigm. One problem concerns EP’s claim that the human mind is massively modular. Our best evidence indicates, instead, that the human mind is adapted to adapt to highly variable and often rapidly changing environments.[5] Our species’ great cognitive achievement was not the evolution of a legion of idiots savants, but the evolution of cortical plasticity, which enables the brain to reorganize itself in response to changing epistemic demands. In this respect, the brain is very similar to the immune system, which manufactures antibodies as needed in response to changing pathogenic demands.[6]

A second problem concerns the doctrine that our minds are adapted to the Stone Age. First, this idea greatly underestimates the rate at which natural and sexual selection can drive evolutionary change. Recent studies have demonstrated that selection can overhaul a species’ adaptations in as few as eighteen generations (for humans, roughly 450 years). Second, the principal driving forces in human psychological evolution have been the demands of competition and cooperation with fellow humans. This created an arms race in human psychological evolution, in which every bit of evolution in human psychology changed the competitive and cooperative environments to which human psychology needed to adapt. And this arms race accelerated the rate of human psychological evolution. So there has undoubtedly been significant human psychological evolution since the Pleistocene. We’re not simply Pleistocene hunter-gatherers, like Fred and Wilma Flintstone, struggling to survive and reproduce in evolutionarily novel suburban habitats.[7]

But this is all highly theoretical stuff. Nothing persuades quite like sound empirical results. And on this score EP has appeared very persuasive. Indeed, EPists boast a number of impressive discoveries, including a sex difference in mate preferences (that males prefer nubility, while females prefer nobility), evolved strategies of infidelity, a sex difference in jealousy, and the reason why stepchildren suffer a high risk of maltreatment. All of these claims have received tremendous media attention, and the coverage has made it appear that these “discoveries” have unassailable evidence in their favor. But a closer look at the evidence reveals ample grounds for skepticism regarding EP’s claims about the nature of the mind. Indeed, there isn’t unequivocal evidence to support EP’s most highly publicized “discoveries.” In what follows, I will focus on three of the most widely cited claims (presented in much greater detail in my recently published book, Adapting Minds).

Her Cheating Mind

In Alfred Kinsey’s classic sex surveys, 50% of married men, and 26% of married women, reported having had extramarital sex.[8] Why? According to EP, since a man’s maximum potential lifetime reproductive output is limited only by the number of pregnancies he can cause, every extramarital encounter represents another potential offspring. But a woman’s maximum potential lifetime reproductive output is limited by the number of pregnancies she can carry to term, and a single mate can provide a woman with all the sperm she needs for those pregnancies. So, EPists ask, what reproductive benefits do women gain from infidelity?

David Buss claims to have the answer: while women can’t increase the quantity of their offspring through extramarital affairs, as men can, they can increase the quality of their offspring. A woman can harvest “good genes” from an extramarital sex partner, and those good genes can provide her offspring with better health, superior disease resistance, and greater attractiveness to the opposite sex. Moreover, as long as she keeps the affair concealed, a woman who has an extramarital affair with a male with good genes gets the reproductive benefits of both worlds: She obtains superior genes for a child who can then be reared on the resources provided by her cuckolded long-term mate with inferior genes. “Some women pursue a ‘mixed’ mating strategy,” says Buss, “ensuring devotion and investment from one man while acquiring good genes from another.”[9]

Because of the reproductive payoffs of this “mixed” mating strategy, women evolved a “psychology of infidelity,”[10] or “a psychological mechanism in women specifically designed to promote short-term mating” when resources have already been secured from a long-term mate, the short-term extrapair sex is likely to go undetected, and the extrapair partner has better genes than the long-term mate.[11] The mechanism that promotes extrapair sex under these conditions is, according to Buss, a female psychological adaptation.

Three findings provide the core evidence for Buss’s claim that female short-term infidelity is an adaptation. First, an interesting study found that, on average, the more symmetrical a male, the higher his attractiveness rating by female panelists.[12] This is significant because many biologists believe symmetry (in which the two sides of the body are mirror images of one another) is a sign of developmental stability, an ability to resist the harmful effects of pathogens and minor mutations. The study also found that highly symmetrical men, on average, reported having been chosen by women as an extrapair sexual partner more often than less symmetrical men. And this, Buss claims, shows that women prefer extrapair partners with good genes.

In another experiment, T-shirts were washed in unscented laundry detergent and issued to male participants who were required to sleep in them for two consecutive nights.[13] During the two-day period, the males were to refrain from using scented soaps, eating spicy foods, drinking alcohol, smoking, and having sex. After the two days, female subjects smelled the T-shirts both during ovulation and during the infertile phase of their menstrual cycles, and they rated each T-shirt for “pleasantness” and “sexiness” of smell. The scents of the T-shirts of highly symmetrical men were rated highest — but only by women who were ovulating. Buss concludes that “women detect the scent of symmetry, prefer that scent when ovulating, and choose more symmetrical men as affair partners.”[14]

Third, in a British study, women who reported extrapair involvements also reported that approximately 60% of their copulations during the fertile phase of their menstrual cycles took place with their extrapair partners, whereas about 60% of their copulations during the infertile phase of their cycles took place with their in-pair partners.[15] So, when women have affairs, the majority of their sexual activity when they are fertile occurs with their affair partners, which tips the odds of paternity in favor of the extrapair partner.

Buss argues that these findings provide rather definitive support for the following picture: women have a long-term mating psychology, which leads them to seek a long-term mate who will provide resources. But, once they’ve landed such a mate, women can become motivated by a psychological mechanism that is “specifically designed to promote short-term mating,” and this will motivate extramarital affairs with males with good genes.

However, the claim that women have a psychological adaptation “specifically designed to promote short-term” infidelity goes well beyond the evidence. In fact, the pattern of female short-term infidelity described by Buss is best explained as a byproduct of other psychological and physiological adaptations, rather than as a direct result of an adaptation specifically for short-term infidelity.

Let’s begin with the question of why women cheat at all. A number of studies, conducted over decades, have consistently found that sexual dissatisfaction in marriage is the leading factor in causing women to engage in short-term extramarital sexual affairs,[16] and these results have recently been corroborated by EPists.[17] Indeed, although women who are emotionally dissatisfied in marriage seek extramarital emotional involvements, they are not more likely than satisfied women to have extramarital sexual affairs; only sexually dissatisfied women are more likely to have extramarital sexual involvements.[18] Moreover, women who are sexually dissatisfied in marriage have been found to be over twice as likely as sexually satisfied women to have extramarital sex.[19] Accordingly, the fact that women engage in short-term extramarital affairs can be explained simply as resulting from a frustrated “sex drive” (for lack of a better term). When the “sex drive” is going unsatisfied in marriage, women sometimes seek sexual satisfaction outside marriage. This may have reproductive benefits, but it is explicable without appeal to a mechanism specifically designed to harvest “good genes” from an extrapair partner.

Of course, while this may explain why women take extramarital sex partners, it doesn’t explain why their sexual activity with their extrapair partners increases during the fertile phase of their menstrual cycles. But several studies have consistently found a peak in the levels of female desire for sex, fantasy about sex, masturbation, and initiation of sex during the fertile phase of the menstrual cycle.[20] The rise in female desire and female-initiated sexual activity during the fertile phase is probably an adaptation, since it is too well designed for reproduction to be an accident or byproduct of something else. So, the increase in sexual activity with extrapair partners during the fertile phase of the menstrual cycle is really just a byproduct of a generalized increase in female-initiated sexual activity during that period.

Buss is aware of this research, but argues that it can’t explain the facts about female short-term infidelity, since it was only sexual activity with extrapair partners, not sexual activity in general, that was found to increase during the fertile phase. But the reason for this extrapair bias is relatively mundane. First, the large majority of women who have extramarital sexual affairs are sexually dissatisfied in their marriages. Second, if a sexually dissatisfied married woman is seeking sexual satisfaction through an extrapair involvement, she will be unlikely to repeat extrapair sexual encounters with men who fail to satisfy, since there are potential costs to getting caught in an infidelity. So, any male who is a regular extrapair partner of a married woman is very likely a man with whom sex is gratifying in a way it is not with her husband. Therefore, when a woman experiences an increased desire for sex during the fertile phase of her cycle, she is far more likely to arrange to have satisfying sex with her extrapair partner than to have unsatisfying sex with her husband.

Still, EPists will argue, none of this explains why women tend to choose symmetrical men as their extrapair partners. But, again, this is merely a byproduct of more general mate preferences. By Buss’s theory, symmetry is one of the things that women seek in a long-term mate because it supposedly signals “good genes.” Even if women have an evolved preference for symmetrical men, this preference may be part of a single set of mate preferences, which is operative in choosing both long-term and short-term mates. To illustrate, suppose that women seek long-term mates who have only two qualities — symmetry and a willingness to provide resources. When a woman seeks a partner for a short-term infidelity, the same preference structure could be operative, but resources become irrelevant. When resources drop out of the equation, only the preference for symmetry remains.

Here, then, is the byproduct explanation of female short-term infidelity. Suppose that women possess the following three adaptations, among others: the “sex drive” (the desire for a regular and fulfilling sex life, together with the patterns of planning and acting so as to ensure the satisfaction of that desire), a peak in sexual desire during the fertile phase of the menstrual cycle (with its attendant increase in female-initiated sexual activity), and a preference for symmetrical males (which is one of several mate preferences). When a woman is sexually dissatisfied in her marriage, she is more likely to begin an extramarital sexual involvement (because of the “sex drive”). In selecting an extrapair partner, the same preferences that were operative in choosing a long-term mate will also be operative, but some of them (for example, a willingness to provide resources) will be irrelevant to the specifically sexual role for which the extrapair partner is being selected. As irrelevant preferences drop out of the selection process, the preference for symmetry comes to loom large, so women will tend to choose symmetrical men as extrapair partners. Then, once a woman begins an extramarital affair, her peaking desire for sex during the fertile phase of her menstrual cycle causes an increase in the number of sexual encounters that she initiates. And, because sex with her husband is less gratifying than sex with her affair partner, the sexual encounters she initiates will be almost exclusively with her extrapair partner, so that sex with her highly symmetrical affair partner will be concentrated during the fertile phase of her menstrual cycle. In this way, the above three adaptations can conspire under circumstances of sexual dissatisfaction in marriage to produce a pattern of behavior that appears to be the direct result of an adaptation specifically for short-term infidelity. So the available evidence doesn’t provide convincing support for the claim that women have an evolved psychological mechanism specifically for strategic infidelity.

His Sexual Jealousy

According to Buss, jealousy is a psychological adaptation, an emotional alarm that is designed to go off whenever we detect signs of a partner’s potential infidelity and to mobilize us to avoid or minimize our reproductive losses. I believe that this hypothesis is one of EP’s significant contributions to our understanding of the human mind. But Buss doesn’t stop here. He further argues that, since men and women faced different threats to reproductive interests throughout human evolutionary history, the sexes have evolved distinct jealousy mechanisms, which “contain dedicated design features, each corresponding to the specific sex-linked adaptive problems that have recurred over thousands of generations of human evolutionary history” (Buss et al., 1999, p. 126). It is a woman’s sexual infidelity, Buss argues, that threatens a man’s reproductive interests by undermining his confidence in paternity and putting him at risk of investing his resources in another man’s offspring. A woman’s reproductive interests, in contrast, are threatened by a male’s emotional involvement with another woman, since that potentially entails a loss of his resources. Thus, Buss hypothesizes, women’s jealousy “is triggered by cues to the possible diversion of their mate’s investment to another woman, whereas men’s jealousy is triggered primarily by cues to the possible diversions of their mate’s sexual favors to another man.”[21]

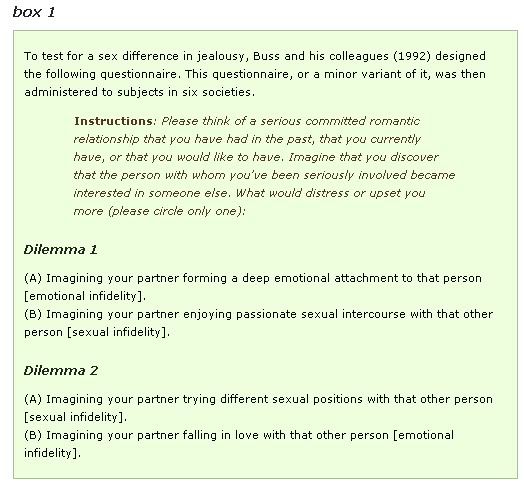

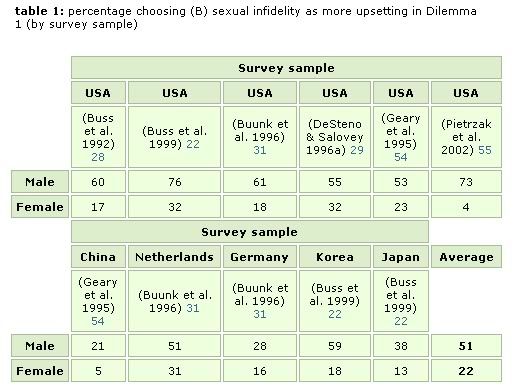

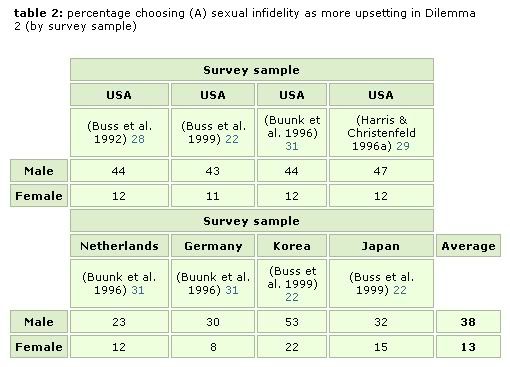

The principal data that Buss cites in support of this theory are responses to forced-choice questionnaires that have been administered in six cultures (Box 1). These data show that significantly more men than women report that the thought of a partner’s sexual infidelity is more distressing than the thought of a partner’s extrapair emotional involvement. In no study did more women than men report sexual infidelity to be more upsetting than emotional infidelity. Indeed, on average, across all studies, many more men than women reported sexual infidelity to be more upsetting than emotional infidelity — 51% of the men versus 22% of the women in response to Dilemma 1 (Table 1), and 38% of the men versus 13% of the women in response to Dilemma 2 (Table 2).

But these results don’t actually confirm Buss’s theory. Buss claims that male jealousy will “focus on cues to sexual infidelity because a long-term partner’s sexual infidelity jeopardizes his certainty of paternity,” whereas female jealousy will focus on cues to emotional infidelity because of potential loss of parental resources.[22] To confirm Buss’s theory, it’s necessary to confirm these predictions — to confirm, for example, that males care more about sexual infidelity than they do about emotional infidelity, not simply that they care more about sexual infidelity than females do. But the data do not show this. Indeed, on average, only half of male subjects chose sexual infidelity as more distressing than emotional infidelity in response to Dilemma 1 (Table 1), and a full 62% chose emotional infidelity over sexual infidelity in response to Dilemma 2 (Table 2).

Moreover, there are some anomalous data for which Buss’s theory can’t easily account. First, there is significant cultural variation in the questionnaire results. While the percentages of males reporting sexual infidelity to be more upsetting than emotional infidelity in response to Dilemma 1 are as high as 76% in a U.S. sample and 59% in the Korean sample, they are as low as 21% in the Chinese sample and 28% in the German sample (Table 1). Similarly, although the percentages of males selecting sexual infidelity in response to Dilemma 2 are as high as 47% in a U.S. sample and 53% in the Korean sample, they are as low as 23% in the Dutch sample and 30% in the German sample (Table 2). These low-side outliers hardly support Buss’ claim that male jealousy is focused on cues of sexual infidelity and that this is true “across cultures.”[23]

Second, the results of three studies in which the infidelity dilemmas were administered to homosexual men are difficult to reconcile with Buss’s claim that there is a sex difference in the evolved “design features” of the psychological mechanisms of jealousy. In one study, only 24% of homosexual men chose sexual infidelity as more upsetting than emotional infidelity in Dilemma 1, and only 5% chose sexual infidelity as more upsetting in Dilemma 2.[24] Another study administered only Dilemma 2 to a sample of homosexual men, of whom only 13% chose sexual infidelity as more upsetting than emotional infidelity.[25] Finally, when both dilemmas were administered to both homosexual and heterosexual men and women, it was found that homosexual men were even less upset by sexual infidelity than were heterosexual women.[26]

Third, the psychologist Christine Harris found that, although heterosexual males who were asked to imagine their partners’ having sex with another male showed greater physiological arousal than those who were asked to imagine their partners’ forming an emotional attachment to another man, males who were asked to imagine having sex with their own partners showed just as great a physiological arousal as those imagining being cuckolded.[27] Indeed, Harris found that there was no significant difference between the one group’s physiological arousal in response to imagined sexual infidelity and the other group’s physiological arousal in response to imagined sexual intercourse. This indicates that the results obtained by Buss and his colleagues are confounded by the fact that males become more aroused by imagining events with sexual content, in general, than by imagining events with emotional content. And this is something that Buss himself has admitted would undermine his theory.[28]

I believe that a more minimal hypothesis concerning the nature of our evolved jealousy mechanism can better account for the data. I call it the relationship jeopardy hypothesis, according to which both sexes have the same evolved capacity to learn to distinguish threatening from nonthreatening extrapair involvements and to experience jealousy to a degree that is proportional to the perceived threat to a relationship in which one has invested mating effort. This same capacity leads to a common sex difference in how infidelities are viewed, however, because the sexes acquire different beliefs about opposite-sex sexual strategies. So the standard sex difference is a product of typical differences in the information believed by the sexes, not of a sex difference in the design of the mechanisms that process that information.

Consider how the relationship jeopardy hypothesis accounts for the data. According to the relationship jeopardy hypothesis, the sexes differ in their acquired beliefs about infidelity, and a series of studies found precisely that.[29] These studies found that men believe that, for women, sex implies love more than love implies sex and that women believe that, for men, love implies sex more than sex implies love. The most dramatic finding was that women believe that it is not that likely that a man’s having sex with a woman implies any kind of emotional involvement with her. Given these beliefs, men should find sexual infidelities more distressing than women because a female’s sexual infidelity signals a potential threat to a relationship (via the likely combination with an emotional involvement) that is greater than the potential threat signaled by a male’s sexual infidelity (which is likely not accompanied by an emotional involvement). Moreover, as we saw earlier, women having extramarital sex are far more likely to be dissatisfied in their marriages than unfaithful men.[30] So, even in the absence of an accompanying emotional involvement, a woman’s sexual infidelity is threatening because it signals dissatisfaction in the relationship in a way that a man’s sexual infidelity does not. Thus, if both sexes have the same evolved capacity to distinguish threatening from nonthreatening infidelities and respond accordingly, we should expect men to find emotional infidelities very threatening, but we should also expect men to find sexual infidelities more threatening to a relationship than women find them. And Buss’s questionnaire results show both effects.

In addition, if the relationship jeopardy hypothesis is correct, if there are cultural differences in the degree to which sexual infidelity is correlated with desertion, then the members of a culture in which there is a weaker correlation between sexual infidelity and desertion should be less bothered by sexual infidelity than the members of a culture in which the correlation is stronger. Interestingly, Buss and his colleagues noted that the German and Dutch “cultures have more relaxed attitudes about sexuality, including extramarital sex, than does the American culture,” and that in the Netherlands “a majority feels extramarital sexual relationships are acceptable under certain circumstances.”[31] Accordingly, German and Dutch males should be less likely than American males to assume that a female partner’s sexual infidelity portends desertion, and consequently they should be less distressed by sexual infidelity than American males. And, on average, 61% of American males chose sexual infidelity as more distressing than emotional infidelity in response to Dilemma 1 (Table 1), and 44% chose sexual infidelity in Dilemma 2 (Table 2). In contrast, on average, only 40% of German and Dutch males chose sexual infidelity in Dilemma 1 (Table 1), and only 26% chose sexual infidelity in Dilemma 2 (Table 2).

Finally, when homosexual and heterosexual men and women were asked their beliefs about relationships and infidelity, the only significant correlation that emerged was between degree of distress over sexual infidelity and the belief that sexual infidelity indicated likely abandonment.[32] All subjects — whether men or women, whether homosexual or heterosexual — were far more likely to be distressed by an imagined sexual infidelity if they believed that sexual infidelity portends the end of a relationship. Further, heterosexual males were by far the most likely to believe that a sexual infidelity is a likely precursor to abandonment. Women, both homosexual and heterosexual, were far more likely than heterosexual men to “discount” a sexual infidelity as nonthreatening to a relationship, and homosexual men were even more likely than women to discount a sexual infidelity as nonthreatening. If these beliefs were processed by the mechanism postulated by the relationship jeopardy hypothesis, it would generate precisely the pattern of questionnaire responses from heterosexual men and women Buss found, but also the responses of homosexual men discussed earlier.

Thus, not only is there not good evidence of Buss’s hypothesized sex difference in the “design features” of the jealous mind, but Buss’s hypothesis doesn’t easily account for a variety of data. In contrast, a simpler hypothesis, according to which there is no sex difference in the “design features” of the mind, but only in the beliefs typically acquired by the sexes, better explains all the data.

His Abuse of Her Children

One of the “discoveries” that Pinker and Buss frequently tout as a signature achievement of EP is the finding, by Martin Daly and Margo Wilson, that children who live with stepparents are at a greater risk of maltreatment than children who live with both genetic parents.33 An evolutionary perspective on human psychology should lead us to expect this, Daly and Wilson argue, because “parental investment is a precious resource, and selection must favor those parental psyches that do not squander it on nonrelatives.”[34]

Daly and Wilson hypothesize that motivational mechanisms of parental love have evolved to be triggered by (genetic) offspring during a “critical period.” Once triggered, parental love serves as “inhibition against the use of dangerous tactics in conflict with the child.”[35] Since these evolved mechanisms of parental love, which inhibit violence, aren’t triggered in substitute (nongenetic) parents, “angry lapses of parental solicitude” in conflictual situations more frequently elicit “the use of dangerous tactics” from substitute parents than from genetic parents.[36] This leads Daly and Wilson to what they call “the most obvious prediction from a Darwinian view of parental motives”: “Substitute parents will generally tend to care less profoundly for children than natural parents, with the result that children reared by people other than their natural parents will be more often exploited and otherwise at risk.”[37] In particular, since stepparenthood is the most common form of substitute parenthood, Daly and Wilson expect stepchildren to be at greater risk than genetic children. Even more particularly, since at least 80% of children living in stepfamilies live with a stepfather and a genetic mother,[38] Daly and Wilson expect that this elevated risk to stepchildren is due to maltreatment at the hands of stepfathers.[39]

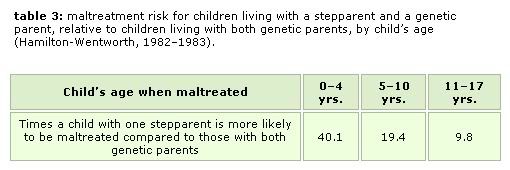

Daly and Wilson cite several studies as confirmation of this prediction, but most provide only indirect evidence, since they lacked important controls. The best direct evidence for this prediction is Daly and Wilson’s landmark 1985 study of 99 cases of child maltreatment in the municipality of Hamilton-Wentworth in Ontario, Canada, during a one-year period from 1982 to 1983.[40] Daly and Wilson found that children under the age of five who lived with a genetic parent and a stepparent were 40.1 times more likely to be victims of maltreatment than same-aged children who lived with both genetic parents (Table 3). The relative risk to stepchildren aged five and up dropped sharply, and even sharper for stepchildren aged eleven and up, but in all age groups children living with a genetic parent and a stepparent were at a significantly greater risk of becoming victims of maltreatment than children living with both genetic parents.

There are, however, three shortcomings of Daly and Wilson’s study. First, Daly and Wilson’s sample consisted of 99 cases of maltreatment, which included not only physical abuse (inflicted injury), but 21 cases of sexual abuse and an unreported number of “unintentional omissions” considered neglect by a child welfare professional. But sexual abuse and physical abuse appear to be distinct phenomena with distinct etiologies. Indeed, intrafamilial child sexual abuse is rarely accompanied by physical abuse,[41] so it doesn’t consist in “the use of dangerous tactics in conflict with the child.” Moreover, in the U.S., the class of “unintentional omissions” often includes allowing truancy and failing to secure a child with a seat belt.[42] These also don’t involve “the use of dangerous tactics in conflict” situations. Since Daly and Wilson claim that stepchildren are at greater risk because the “inhibition against the use of dangerous tactics in conflict” is not triggered in stepparents, cases of maltreatment that don’t involve the use of dangerous tactics in conflict don’t belong in the sample against which to test their prediction. If we want to understand the “lapses of parental love” that result in “the use of dangerous tactics in conflict with the child,” as Daly and Wilson claim, we should explore data regarding physical abuse, rather than the amorphous category of maltreatment, to test whether substitute parents are more physically abusive than genetic parents.

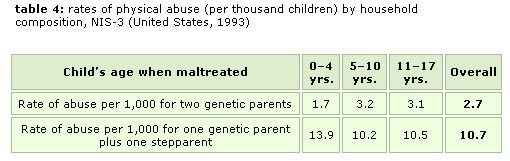

In order to test Daly and Wilson’s prediction against a much larger and far more representative sample of cases of physical abuse, Elliott Smith, the Associate Director of the National Data Archive on Child Abuse and Neglect, and I analyzed child abuse data compiled in the Third National Incidence Study of Child Abuse and Neglect (NIS-3). We found that children under the age of five living in a stepfamily were 8.2 times more likely to be physically abused than same-aged children living with both genetic parents (Table 4), which is drastically lower than the 40-times-greater risk of maltreatment that Daly and Wilson found. And children aged five and above who lived in a stepfamily were only 3.3 times more likely to be physically abused than same-aged children living with both genetic parents.

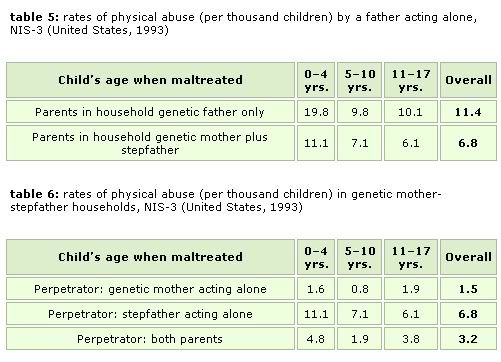

While not as dramatic as Daly and Wilson’s findings, these results nonetheless appear to confirm Daly and Wilson’s prediction. But this brings us to the second methodological shortcoming of Daly and Wilson’s study. Daly and Wilson’s data concern the risk of maltreatment to children living in households of varying parental composition, rather than a child’s risk of being maltreated by a stepparent or genetic parent. That is, Daly and Wilson’s data don’t identify the perpetrators of maltreatment, even though their hypothesis predicts that stepfathers will be disproportionately represented among perpetrators. Since the NIS-3 data identified perpetrators, they allow a more direct test of Daly and Wilson’s prediction, and those data yield two surprises. First, in a clear anomaly for Daly and Wilson’s hypothesis, single genetic fathers were actually 1.7 times more likely than stepfathers to physically abuse their children (Table 5). Second, the data on physical abuse of children living with a genetic mother and a stepfather show that genetic mothers are involved in a significant portion of that abuse, either acting alone or in concert with the stepfather (Table 6).

Nonetheless, children who were abused by a parent acting alone were 4.5 times more likely to be abused by their stepfather than by their genetic mother (Table 6), and this does appear to confirm Daly and Wilson’s prediction. But this brings us to the third of the methodological shortcomings of Daly and Wilson’s study, which is a shortcoming of our NIS-3 study as well. Daly and Wilson’s sample and the NIS-3 sample consisted entirely of officially reported cases of child maltreatment — that is, cases of maltreatment that were brought to the attention of a professional who worked in a capacity concerned with child welfare, were investigated in some way by that professional or others to whom the cases were referred, and were determined to be genuine cases of child maltreatment by the investigators. But some family violence researchers have pointed out that child welfare professionals sometimes take the presence of a stepparent in the household into consideration in deciding whether a bruise or broken bone resulted from an accident or abuse.[43] That is, many child welfare professionals take the presence of a stepparent in a household to be partly diagnostic of maltreatment. So, Gelles and Harrop argue, “injuries to children with non-genetic parents are more likely to be diagnosed and reported as abuse.”[44] As a result, official case reports of child maltreatment may contain a bias against stepparents, which distorts the facts concerning the relative rates of maltreatment by stepparents and genetic parents.

Daly and Wilson are fully aware of the potentially confounding effects of diagnostic bias on their studies, but they dismiss it with the following single argument: “If reporting or detection biases were responsible for the overrepresentation of stepparents among child abusers, then we would expect the bias, and hence the overrepresentation, to diminish as we focused upon increasingly severe and unequivocal maltreatment up to the extreme of fatal batterings.”[45] “At the limit,” they argue, “we can be reasonably confident that child murders are usually detected and recorded.”[46] When Daly and Wilson examined “validated” cases of child homicide in America[47] and cases of child homicide in Canada that were “known to Canadian police,”[48] they found that stepchildren were far more likely to be victims of fatal maltreatment than children living with both genetic parents. Thus, Daly and Wilson conclude that comparable findings regarding non-fatal maltreatment are not confounded by a reporting bias against stepparents.

There is substantial evidence, however, that “validated” child homicides and those “known to police” are but a partial record of child maltreatment fatalities in the United States, and there is little reason for doubting that Canada is similar in this regard. Indeed, when review boards undertook comprehensive studies of up to nine sources of information about each child fatality in four U.S. states, they consistently found that only 40–50% of all identifiable child maltreatment fatalities, including inflicted injury fatalities, were coded as maltreatment fatalities on death certificates or in police records.[49] The remainder were coded as accidental deaths or, more commonly, deaths due to an “undetermined manner.”

More importantly, analysis of Colorado records revealed direct evidence of a potential diagnostic bias against “stepfathers.”[50] For maltreatment fatalities at the hands of “other relatives,” which included legally married stepfathers, were 1.37 times more likely to be recorded as maltreatment fatalities on death certificates than were maltreatment fatalities perpetrated by genetic parents. Moreover, maltreatment fatalities at the hands of “other unrelated” individuals, which included “live-in boyfriends” of victims’ mothers, were 8.71 times more likely to be recorded as such on death certificates than maltreatment fatalities at the hands of genetic parents. This last fact is particularly important for two reasons. First, Daly and Wilson classified “live-in boyfriends” as stepfathers (as did Smith and I).[51] Second, in the Canadian filicide data mentioned above, Daly and Wilson found that “common-law” stepfathers accounted for a full 89% of the filicides that were attributed to stepfathers in police records.[52] Thus, “common-law” stepfathers, who almost single-handedly accounted for the higher rate of filicide among stepfathers in Daly and Wilson’s study, were in a group that is 8.71 times more likely than genetic parents to have a perpetrated child maltreatment fatality actually identified as a maltreatment fatality in official records.

If, as Daly and Wilson argue, the effects of any reporting bias should be less in cases of fatal maltreatment than in cases of non-fatal abuse, this degree of reporting bias in U.S. cases of fatal maltreatment implies a higher degree of reporting bias in cases of non-fatal abuse, which is then more than sufficient to account for the overrepresentation of stepchildren in the NIS-3 data (Table 4). So, available evidence indicates that American physical abuse data are sufficiently confounded by reporting bias that they can’t confirm Daly and Wilson’s hypothesis, and there is little reason to think that the Canadian records are immune to this problem. Since all of our evidence to date concerning stepparental abuse derives from official case reports, we simply don’t know whether stepparents are more likely than genetic parents to abuse their children. Daly and Wilson’s claim that stepparents are more likely than genetic parents to abuse their children goes beyond the available reliable evidence.

Conclusion

I’ve argued that some of the principal pieces of evidence cited in support of three of Evolutionary Psychology’s highly publicized “discoveries” in fact fail to establish EP’s claims. And I argue in Adapting Minds that other evidence cited in support of these “discoveries” suffers similar evidentiary problems. EP’s other “discoveries” enjoy no better empirical support. For example, I argue in Adapting Minds that the evidence fails to establish Buss’s claims about evolved mate preferences (that males are fixated on nubility, while females are fixated on nobility) and Cosmides’ claim that we have an evolved module for detecting cheaters in social exchanges.[53] Although EP is a bold and innovative explanatory paradigm, it has not provided convincing evidence for its claims about the nature and evolution of human psychology. We really don’t yet know how to understand human psychology from an evolutionary perspective. Perhaps some day we will achieve that understanding, but that day is not at hand. Coming to terms with the shortcomings of Evolutionary Psychology, however, may help us eventually achieve a new and improved evolutionary psychology.

References

1. Caporael, Linnda R. 2001. “Evolutionary Psychology: Toward a Unifying Theory and a Hybrid Science.” Annual Review of Psychology 52: 607–628.

2. Cosmides, Leda, and John Tooby (1997). The Modular Nature of Human Intelligence. In A. B. Scheibel and J. W. Schopf (Eds.), The Origin and Evolution of Intelligence (pp. 71–101). Sudbury, MA: Jones and Bartlett.;

Pinker, Steven. 1997. How the Mind Works. New York: W. W. Norton.;

Tooby, John, and Leda Cosmides (2000). Toward Mapping the Evolved Functional Organization of the Mind and Brain. In M. S. Gazzaniga (Ed.), The New Cognitive Neuro-sciences (second ed., pp. 1167–1178). Cam-bridge, MA: MIT Press.

3. Tooby, John, and Leda Cosmides. 1990. “The Past Explains the Present: Emotional Adaptations and the Structure of Ancestral Environments.” Ethology and Sociobiology 11: 375–424.

4. Tooby, John, and Leda Cosmides. 1992. “The Psychological Foundations of Culture.” In J. H. Barkow, L. Cosmides and J. Tooby (Eds.), The Adapted Mind: Evolutionary Psychology and the Generation of Culture (pp. 19–136). New York: Oxford University Press.

5. Sterelny, Kim. 2003. Thought in a Hostile World: The Evolution of Human Cognition. Malden, MA: Blackwell.

6. Buller, David J. 2005. Adapting Minds: Evolutionary Psychology and the Persistent Quest for Human Nature. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, chapter 4.

7. Buller, 2005, chapter 3.

8. Kinsey, Alfred C., Wardell B. Pomeroy, and Clyde E. Martin. 1948. Sexual Behavior in the Human Male. Philadelphia: W. B. Saunders.;

Kinsey, Alfred C., Wardell B. Pomeroy, Clyde E. Martin, and Paul H. Gebhard. 1953. Sexual Behavior in the Human Female. Philadelphia: W. B. Saunders.

9. Buss, David M. 2000. The Dangerous Passion: Why Jealousy Is as Necessary as Love and Sex. New York: Free Press, 162.

10. Buss 2000, 159.

11. Greiling, Heide, and David M. Buss. 2000. “Women’s Sexual Strategies: The Hidden Dimension of Extra-Pair Mating.” Personality and Individual Differences 28: 929–963, 960.

12. Gangestad, Steven W., and Randy Thornhill. 1997. “The Evolutionary Psychology of Extrapair Sex: The Role of Fluctuating Asymmetry.” Evolution and Human Behavior 18: 69–88.

13. Thornhill, Randy, and Steven W. Gangestad. 1999. “The Scent of Symmetry: A Human Sex Pheromone That Signals Fitness?” Evolution and Human Behavior 20: 175–201.

14. Buss 2000, 162.

15. Baker, R. Robin, and Mark A. Bellis. 1993. “Human Sperm Competition: Ejaculate Manipulation by Females and a Function for the Female Orgasm.” Animal Behaviour 46: 887–909.

16. Terman, Lewis M. 1938. Psychological Factors in Marital Happiness. New York: McGraw-Hill.;

Chesser, Eustace. 1956. The Sexual, Marital and Family Relationships of the English Woman. London: Hutchinson’s Medical Publications.;

Bell, Robert R., and Dorthyann Peltz. 1974. “Extramarital Sex among Women.” Medical Aspects of Human Sexuality 8: 10–31.;

Tavris, Carol, and Susan Sadd. 1975. The Redbook Report on Female Sexuality. New York: Delacorte.;

Glass, Shirley P., and Thomas L. Wright. 1985. “Sex Differences in Type of Extramarital Involvement and Marital Dissatisfaction.” Sex Roles 12: 1101–1120.;

Glass, Shirley P., and Thomas L. Wright. 1992. “Justifications for Extramarital Relationships: The Association between Attitudes, Behaviors, and Gender.” Journal of Sex Research 29: 361–387.;

17. Greiling and Buss 2000.

18. Glass and Wright 1985, 1992.

19. Bell and Peltz 1974; Tavris and Sadd 1975.

20. Adams, David B., Alice Ross Gold, and Anne D. Burt. 1978. “Rise in Female-Initiated Sexual Activity at Ovulation and Its Suppression by Oral Contraceptives.” New England Journal of Medicine 299: 1145–1150.;

Hill, Elizabeth M. 1988. “The Menstrual Cycle and Components of Human Female Sexual Behaviour.” Journal of Social and Biological Structures 11: 443–455.;

Stanislaw, Harold, and Frank J. Rice. 1988. “Correlation between Sexual Desire and Menstrual Cycle Characteristics.” Archives of Sexual Behavior 17: 499–508.;

Regan, Pamela C. 1996. “Rhythms of Desire: The Association between Menstrual Cycle Phases and Female Sexual Desire.” Canadian Journal of Human Sexuality 5: 145–156.

21. Buss, David M. 1994. The Evolution of Desire: Strategies of Human Mating. New York: Basic Books, 128.

22. Buss, David M., Todd K. Shackelford, Lee A. Kirkpatrick, Jae C. Choe, Hang K. Lim, Mariko Hasegawa, et al. 1999. “Jealousy and the Nature of Beliefs About Infidelity: Tests of Competing Hypotheses About Sex Differences in the United States, Korea, and Japan.” Personal Relationships 6: 125–150, 125.

23. Buss, David M. 1999. Evolutionary Psychology: The New Science of the Mind. Boston: Allyn and Bacon, 326.

24. Sheets, Virgil L., and Marlow D. Wolfe. 2001. “Sexual Jealousy in Heterosexuals, Lesbians, and Gays.” Sex Roles 44: 255–276.

25. Harris, Christine R. 2002. “Sexual and Romantic Jealousy in Heterosexual and Homosexual Adults.” Psychological Science 13: 7–12.

26. Bailey, J. Michael, Steven Gaulin, Yvonne Agyei, and Brian A. Gladue. 1994. “Effects of Gender and Sexual Orientation on Evolutionarily Relevant Aspects of Human Mating Psychology.” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 66: 1081–1093.

27. Harris, Christine R. 2000. “Psychophysiological Responses to Imagined Infidelity: The Specific Innate Modular View of Jealousy Reconsidered.” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 78: 1082–1091.

28. Buss, David M., Randy J. Larsen, Drew Westen, and Jennifer Semmelroth. 1992. “Sex Differences in Jealousy: Evolution, Physiology, and Psychology.” Psychological Science 3: 251–255, 255.

29. DeSteno, David A., and Peter Salovey. 1996a. “Evolutionary Origins of Sex Differences in Jealousy?” Psychological Science 7: 367–372.;

DeSteno, David A., and Peter Salovey. 1996b. “Genes, Jealousy, and the Replication of Misspecified Models.” Psychological Science 7: 376–377.;

Harris, Christine R., and Nicholas Christenfeld. 1996a. “Gender, Jealousy, and Reason.” Psychological Science 7: 364–366.;

Harris, Christine R., and Nicholas Christenfeld. 1996b. “Jealousy and Rational Responses to Infidelity across Gender and Culture.” Psychological Science 7: 378–379.

30. Glass and Wright 1985, 1992.

31. Buunk, Bram P., Alois Angleitner, Viktor Oubaid, and David M. Buss. 1996. “Sex Differences in Jealousy in Evolutionary and Cultural Perspective: Tests from the Netherlands, Germany, and the United States.” Psychological Science 7: 359–363.

32. Sheets and Wolfe 2001.

33. Daly, Martin, and Margo Wilson. 1985. “Child Abuse and Other Risks of Not Living with Both Parents.” Ethology and Sociobiology 6: 197–210.

34. Daly, Martin, and Margo Wilson. 1988. Homicide. New York: Aldine de Gruyter, 83.

35. Ibid., 75.

36. Ibid.

37. Ibid., 83.

38. Daly, Martin, and Margo Wilson. 1994. “Some Differential Attributes of Lethal Assaults on Small Children by Stepfathers Versus Genetic Fathers.” Ethology and Sociobiology 15: 207–217, 208.;

Buller, 2005, 389.

39. Daly, Martin, and Margo Wilson. 1999. The Truth About Cinderella: A Darwinian View of Parental Love. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

40. Daly and Wilson, 1985.

41. Parker, Hilda, and Seymour Parker. 1986. “Father-Daughter Sexual Abuse: An Emerging Perspective.” American Journal of Orthopsychiatry 56: 531–549.

42. Christoffel, Katherine Kaufer, Peter C. Scheidt, Phyllis F. Agran, Jess F. Kraus, Elizabeth McLoughlin, and Jerome A. Paulson. 1992. “Standard Definitions for Childhood Injury Research: Excerpts of a Conference Report.” Pediatrics 89: 1027–1034.

43. Gelles, Richard J., and John W. Harrop. 1991. “The Risk of Abusive Violence among Children with Non-Genetic Caretakers.” Family Relations 40: 78–83.;

Giles-Sims, Jean. 1997. “Current Knowledge About Child Abuse in Stepfamilies.” Marriage and Family Review 26: 215–230.;

Giles-Sims, Jean, and David Finkelhor. 1984. “Child Abuse in Stepfamilies.” Family Relations 33: 407–413.

44. Gelles, 1991, 79.

45. Daly and Wilson, 1988, 88.

46. Daly and Wilson, 1999, 31.

47. Daly and Wilson, 1988, 88–89.

48. Daly, Martin, and Margo Wilson. 2001. “An Assessment of Some Proposed Exceptions to the Phenomenon of Nepotistic Discrimination against Stepchildren.” Annales Zoologici Fennici 38: 287–296, 291.

49. Christoffel, Katherine K., Nora K. Anzinger, and David A. Merrill. 1989. “Age-Related Patterns of Violent Death,” Cook County, Illinois, 1977 through 1982. American Journal of Diseases of Children 143: 1403–1409.;

Ewigman, Bernard, Coleen Kivlahan, and Garland Land. 1993. “The Missouri Child Fatality Study: Underreporting of Maltreatment Fatalities among Children Younger Than Five Years of Age,” 1983 through 1986. Pediatrics 91: 330–337.;

Herman-Giddens, Marcia E., Gail Brown, Sarah Verbiest, Pamela J. Carlson, Elizabeth G. Hooten, Eleanor Howell, et al. 1999. “Underascertainment of Child Abuse Mortality in the United States.” Journal of the American Medical Association 282(5): 463–467.;

Crume, Tessa L., Carolyn DiGuiseppi, Tim Byers, Andrew P. Sirotnak, and Carol J. Garrett. 2002. “Underascertainment of Child Maltreatment Fatalities by Death Certificates,” 1990–1998. Pediatrics 110(2): e18.

50. Crume et al. 2002.

51. Daly and Wilson, 1985.

52. Daly and Wilson, 2001, 291.

53. Cosmides, Leda. 1989. “The Logic of Social Exchange: Has Natural Selection Shaped How Humans Reason? Studies with the Wason Selection Task.” Cognition 31: 187–276.

54. Geary, David C., Michael Rumsey, C. Christine Bow-Thomas, and Mary K. Hoard. 1995. “Sexual Jealousy as a Facultative Trait: Evidence from the Pattern of Sex Differences in Adults from China and the United States.” Ethology and Sociobiology 16: 355–383.

55. Pietrzak, Robert H., James D. Laird, David A. Stevens, and Nicholas S. Thompson. 2002. “Sex Differences in Human Jealousy: A Coordinated Study of Forced-Choice, Continuous Rating-Scale, and Physiological Responses on the Same Subjects.” Evolution and Human Behavior 23: 83–94.

Comments

will format and fix tables

will format and fix tables now

nice one, interesting stuff.

nice one, interesting stuff.