Against the romanticizing of education, Leftists should recognize alternative regimes of study, as practiced in prison organizing and indigenous peoples’ movements, and participate with them toward dismantling the intertwined regimes of education and carcerality.

Left movements in North America romanticize education in many ways. Calls to “defend public education” emanate from the most radical movements of students, like the ‘Maple Spring’ in Quebec, and teachers, like the social justice-oriented Chicago Teachers Union. In struggles against prisons, with images of the ‘school-to-prison pipeline’ and calls for ‘education not incarceration,’ we on the Left often criticize contemporary education as corrupted for disproportionately funneling poor youth of color into the penal regime. Conversely, in organizing around universities, the university has been framed as losing its educational mission and becoming like a prison, an “ivory cage,” which “incarcerates” potentially resistant young people behind walls of debt.

This fetishizing of education is a key obstacle to Left movements’ revolutionary goals. Seeing ‘revolution’ as an overturning of a dominant order, a revolutionary movement would need to radically transform all of the regimes composing that order—from the family and work to transportation and prisons. Such a movement is hindered if any one of these regimes is immunized from critique. That is precisely what has happened with the regime of education.

We have a strong desire to assume that a non-racist, liberating education is possible. But who is this ‘we’? People talking about “saving public education” tend to be associated with Higher Ed institutions in some way, whether from working in or graduating from one. This desire seems to be far less evident in people who haven’t invested their identity in such an institution. People who are engaged in struggles that strike directly at the heart of the dominant order—like prison labor strikes and hunger strikes—tend not to ask for anything about this order to be saved. In their struggles, they are practicing an alternative to education—mapping and building social relations across prison cells, analyzing the terrain of surveillance for blindspots, experimenting with covert communication techniques, formulating effective demands, etc.—practices of collective studying that makes their organizing a kind in which “every crook can govern.” To reduce prisoners’ autonomous study to education would not only disrespect their ingenuity but also foreclose the possibility of studying with them across the prison walls.

A revolutionary alternative to education can also be seen in indigenous people’s struggles to undo the ongoing history of dispossession from their lands, for instance, with the Indigenous Nationhood Movement. With direct actions, such as blockades against fracking, they practice an insurgent politics toward abolishing the flows of commodified resources that churn the gears of capitalism. Indigenous peoples simultaneously enact a resurgent politics through reclaiming their land, revitalizing their cultural traditions, and reconnecting their lives in relations of reciprocity with the non-human world. In insurgence and resurgence, indigenous peoples study with each other in ways that are radically alternative to those of education.

Reflecting on these contrasts can draw out what is at stake in my call to de-romanticize education. Prisoners’ study and indigenous study are practices for composing alternative worlds—not alternative forms of modernity, but alternatives to modernity and its underside of colonial-racial-hetero-patriarchal-capitalism. Naïve faith in education gives a shortcut around the challenges of integrating study with revolutionary organizing. Instead, we should drop the abstract concept of ‘education’ in favor of the differentiating concept of ‘regimes of study’—that is, sets of practices, institutions, and processes that enroll people in particular ways of knowing, teaching, and learning. The major regime of study today is the education-based regime. Its key features are credentialed experts who teach and give exams, which prepare students for participation in governance.

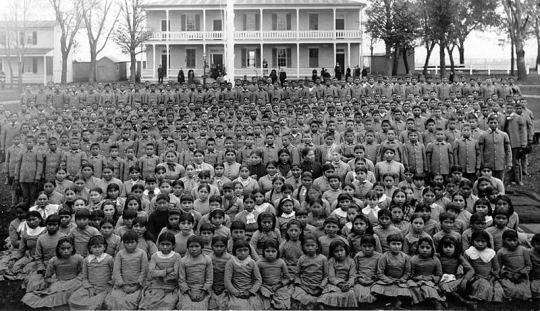

Pupils at Carlisle Indian Industrial School, Pennsylvania (c. 1900). Image via Wikicommons

Pupils at Carlisle Indian Industrial School, Pennsylvania (c. 1900). Image via Wikicommons

There are many alternative regimes of study associated with ways of composing the world alternative to modern/colonialist capitalism. To promote a regime of study based on continual circulation of study-knowledge-and-teaching, we can take the relay from indigenous communities, DIY study groups embedded in organizing, as well as movements that have sought to contest the education regime’s control of the resources for study. The Black Campus Movement sought to abolish the White University and expropriate its resources for Black study. American Indian and First Nations movements sought to replace the Colonial University with the Indigenous University. Feminist and Queer movements sought to abolish the Hetero-Patriarchal University. Communist movements sought to abolish the Capitalist University.

In these movements—and often in radical struggles—what participants called ‘education’ would have been better described as an alternative regime of study. Calling for their own kind of ‘education’ can have politically useful, tactical purposes (e.g., making a claim on the resources assigned for ‘education’). But, it also has many pitfalls from confusing their own resistant practices with those of what they are struggling against. Thus, I argue for using the language of ‘regimes of study’ for analytical purposes—i.e., in developing critical analyses of strategy, visions, etc., which can include discussion of uses of 'education.’ In a particular struggle, for instance, to take over a campus and foster an alternative regime of study in that place, the movement could tactically use slogans like 'defend public education' but, simultaneously, have some critical analysis amongst their group about how they are seeking to avoid reproducing the education-based regime of study and to enact and foster alternatives to it.

The revolutionary campus movements fell far short of their goals, as evidenced by the marginalization of their projects within small ‘Studies’ departments and by the predominance throughout the wider academy of the projects they sought to destroy. Resistant study projects still emerge from these departments and they occasionally connect with wider movements. Yet, the game is rigged against them, as the wider institutions of universities are fully enmeshed in the education-based regime of study—on the top of the pyramid of education.

Despite education administrators’ tight rule over the pyramid, alternative practices of study happen in its cracks. Students create a group against sexual violence. Custodians coordinate a work slowdown. Contingent faculty organize a union. In their organizing, they integrate practices of study—such as mapping the campus and their social relations—that have nothing to do with the education regime’s exams and expertise. They contest the use of the university as a place for study.

The education regime’s way of seeing the world relies on a view of time as separate from space and as linear and developmental, on a two-dimensional scale. Students who subscribe to this view see themselves as individuals hurtling into a future with possible trajectories of either going ‘up’ as a valued graduate toward economic productivity or ‘down’ as a ‘dropout’ toward criminality. This discourse of ‘dropout’/’graduate’ was developed in the 1960s to stigmatize potentially resistant youth through individualizing of responsibility for social crises onto future-oriented students. As an antidote, we can draw from indigenous conceptions of the world that refuse such individualizing imaginaries through their rejection of dichotomized ‘space’ and ‘time.’ Grounding our bodies in particular places, we can make meaning for our lives through telling stories about our relations with these places and the people and things in them.

A first step for such a re-grounding has to be to acknowledge that universities and prisons are built on indigenous land, and that the dispossession of indigenous peoples from that land was the key precondition for building the regimes of racial capitalism on it. We can unsettle our ‘selves’ and our relations with these places through reconnecting with the land in ways that take responsibility for undoing the mess of settler colonialism. Indigenous movements have often reoccupied land for purposes of decolonizing and resurgence, such as the Alcatraz occupation of 1969-1971. Likewise, the Black Campus Movement occupied buildings, such as the Allen Building at Duke University in 1969, creating the Malcolm X Liberation University.

Allen Building takeover at Duke University - protesters attacked with tear gas (image via).

Allen Building takeover at Duke University - protesters attacked with tear gas (image via).

The state reacted with infiltration of the movements and repression of their most militant leaders, often imprisoning them. This was the beginning of the era of mass incarceration. The movement kept their relationships alive across the prison walls through prisoner support groups and occasional jailbreaks.

In some contemporary struggles at universities, the places have becomes sites for re-articulating new relationships in and through regimes of study alternative to that of education. In the occupation of Wheeler Hall at Berkeley in 2009, students and workers broke “the glass floor” through creating affective relationships, or “lines of care,” between their bodies across police barricades. Some participants have highlighted the difficulties of bridging these campus struggles with movements against policing and incarceration of working class people of color in nearby neighborhoods, such as East Oakland.

The Left creates its own imaginal obstacles to seeing how prisons and universities are co-constitutive through subscribing to liberal narratives, like ‘dropout’/’graduate’ and ‘school to prison pipeline,’ that romanticize education and see incarceration as its despised Other. Some projects are taking on these obstacles, such as Damien Sojoyner’s de-mystifying of the ‘school to prison pipeline’ by showing how schools have long been places of policing young people, with a case study of Los Angeles’s programs of police in schools in the 1960s as means of suppressing Black Radicalism and normalizing racial oppression. Through such critical historicizing of the ‘school to prison pipeline’ metaphor, it can become a useful tool for drawing attention to the long-standing co-implication of schools and prisons as disciplinary institutions of racial capitalism.

By contrast, the ‘education not incarceration’ framing—with its naïve treatment of education as a social good—might be impossible to recuperate for radical purposes. Conversely, comparisons of universities with prisons, such as implying deviation from their educational mission into becoming “ivory cages,” also pose such an extreme challenge, though perhaps not insurmountable. Such comparisons can foreclose thinking about the ways that the institutions are co-constituted with each other within racial capitalism. Yet, if framed carefully, they can also be used to show how the institutions share common logics—they both perpetuate logics of the regimes of carcerality and education, which are instantiated in crucially different but inter-related ways. The problem of romanticizing education (and conversely, demonizing incarceration) often arises from a failure to make these distinctions between 'institutions' and 'regimes,' their different types, and how they are related. Comparisons tend to imply assuming the possibility of creating institutions of schools and universities that are ideally free of carcerality and full of education. Such an ideal is romanticizing because the regimes of carcerality and education have always co-constituted each other and infused all institutions of racial capitalism.

Against this historical neglect, movements should articulate our ideals in ways that call for schools and universities free not only of carcerality but of education as well. Inspired by the revolutionary campus movements who fought for a ‘Black University’ and an ‘Indigenous University,’ we should demand, not ‘free education,’ but ‘freedom from education.’ Through reoccupying the places that have been used for both education and carcerality, we can turn them toward other purposes: to enact alternative regimes of study in and for our revolutionary movements.

One of the American Indian Movement’s “first actions was to support the nineteen-month occupation of Alcatraz, the abandoned island prison off the coast of San Francisco, that an ad hoc group of Indigenous activists had seized. The proclamation announcing the occupation declared that reservations already resembled abandoned prisons.” – Dan Berger, The Struggle Within - (image via)

One of the American Indian Movement’s “first actions was to support the nineteen-month occupation of Alcatraz, the abandoned island prison off the coast of San Francisco, that an ad hoc group of Indigenous activists had seized. The proclamation announcing the occupation declared that reservations already resembled abandoned prisons.” – Dan Berger, The Struggle Within - (image via)

In addition to such de-romanticizing, the best paths toward breaking down these obstacles are through study embedded in organizing with the people who are most affected by the brutal, exploitative functions of both prisons and universities. The beginning of an abolitionist regime of study can be created through connecting with campus workers and students who are more likely to have friends and loved ones in the penal system. Collaborating together, they can build relationships and communicative, co-research projects with the inmates of jails and prisons so as to amplify the voices of those inside.

At the same time, refusing to fall back on a view of education as redemption, those working and studying on Higher Ed campuses can take the relay from the revolutionary energies of their inmate collaborators. Seeing the regimes governing the spaces inside the campus and the prison as serving inversely related functions in the same racial capitalist, settler colonial world, they can devote their energies to expropriating the resources of their campuses and organizing and studying for a decolonial, abolitionist world in which there would be no prisons—and maybe no universities either.

……..

Abraham Bolish [pseudonym] is an independent researcher who lives and organizes in the Southeastern United States.

Comments

The very concept of education

The very concept of education within a capitalist society is surely false. The correct term should be "brainwashed" subduecation". (how the fuck do you spell it) To turn us into useful tools for the capitalist "meat grinder"