The story of the first successful squatters of private property in Lambeth. In 1972, Olive Morris and Liz Turnbull, both members of the Brixton Black Panthers, occupied a flat above a launderette in Railton Road and successfully fought off attempts at illegal eviction. In doing so, they set an example for hundreds of homeless young people in Brixton and the flat remained squatted for many years.

At the end of 1972, Olive Morris and Liz Turnbull (Obi) found themselves without a place to live and not much money to rent. Taking the cue from a group of white women who had squatted a building on Railton Road and were running a Women’s Centre, they decided to inspect the area and find a suitable property.

They settled for 121 Railton Road, an empty privately owned property on a corner, with a shop on the ground floor. They squatted the building, and made it their home. As opposed to Council owned property, squatting private buildings was a much more tricky affair. The owners and property agents waged war against squatters, aided by a local police force only too happy to get their hands on the job of harassing Black youth, whose behavior was mostly construed as being either criminal or subversive.

Liz and Olive resisted several eviction attempts, and were arrested in many occasions. Every time, they went back to the squat and just carried on. The most notorious of the evictions was well documented in the local press. On a January morning of 1973, while Olive was away at work, the police forcefully took Liz from the house and brought her to the police station. When Olive returned to the house, she simply got back in the building. The police came back to take her away too, but Olive climbed onto the roof of the house and from there she harangued the policemen on the street.

Pictures from the day appeared in local papers, and several years after the episode the iconic photograph of Olive climbing onto the roof of the building went on to the cover of the Squatters Handbook 1979 Edition.

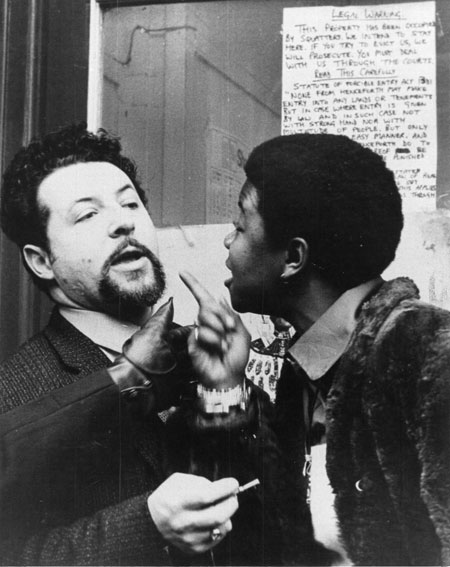

This picture from 1973 shows Olive confronting a rather overwhelmed property agent Mr Defries, whilst in the background a sign proclaims:

LEGAL WARNING

THIS PROPERTY HAS BEEN OCCUPIED BY SQUATTERS. WE INTEND TO STAY HERE. IF YOU TRY TO EVICT US, WE WILL PROSECUTE. YOU MUST DEAL WITH US THROUGH THE COURTS.

And so the owners of the building did. Eventually, after resisting several evictions, and going through legal steps that made it very hard for them to remain squatting the same property, Liz and Olive decided to move down the road and squat a Council property at 64 Railton Road. 121 Railton Road was continued to be used for meetings of Black organisations, and the Sabaar Bookshop was also run from the premises.

Lambeth Council purchased the property at some point during the 80s, and the building continued to be squatted by anarchists and feminists from 1981 until the final eviction in 1999, making it one of the longest squats in the history of Brixton.

The squatters movement in Brixton was particularly strong, starting at the end of the 50s and stretching well into the 90s. Housing shortages in Lambeth were severe. In A History of Brixton, Alan Piper explains how after the Second World War the combination of damage caused by the bombings and rent controls introduced after the First World War, meant that in Lambeth no one was building to rent, whilst the existing housing stock was deteriorating quickly. Demand for accommodation from West Indian immigrants was high. For the Black population it was particularly hard to find decent and affordable accommodation. John Salaway, in his book about the 1981 Brixton riots, refers to the housing crisis of the 70s:

Sheila Patterson suggests that Lambeth Council, managing a slum clearance resettlement putting enormous pressure on waiting lists, was deliberately allowing Black overcrowding of properties go unchecked so that tenants would not have to be re-housed in Council property.

The Council was busy demolishing the slums and rehousing their population in newly built Council Estates such as Angel Town and Stockwell Park. Private owners were either selling their run down property to West Indians at extortionate prices, or to developers that accumulated properties and simply let them crumble away empty, waiting to cash on the promised regeneration of the area. Lambeth Council had in the pipeline ambitious plans for demolition and development, and so repairs were not being made to their existing housing stock.

From: A decade of squatting: The story of squatting in Britain since 1968 by Steve Platt

For those people who fell between the twin stools of home ownership and council housing (ie those who would traditionally have been housed in the private sector), opportunities were shrinking, rents rocketing and security diminishing. This increasing desperation of people at the bottom end of the housing market together with the growing number of empty houses, led to the growth of squatting both in scale and scope.

[...]

By the end of 1975 unlicensed squatting had almost established itself as a routine method of finding housing in the short term. A number of housing officials stated in private that squatting had to be tolerated, quite simply because it was impossible to envisage any alternative for the estimated 40-50,000 squatters. The Advisory Service for Squatters (ASS) reported in a press release that housing aid centres, social service departments, citizens advice bureaux, probation services and even the police were regularly referring people to them. Brixton Women’s Centre [the so-called White Women Centre also located in Railton Road] received as many as 30-40 referrals in one week from Lambeth Social Services Department.

Official attitudes towards squatting were, however, paradoxical. While there was often a measure off acceptance of squatting as inescapable, even necessary, there was also strong determination to bring it under control. As an officer’s report in November 1974 to Lambeth Council’s Housing Committee put it: “The council is faced with a situation which is clearly out of control and the need is to bring it under control as quickly as possible”.

There are several references to the 121 Railton Road on squatters and anarchist online literature, but aside from Steve Platt’s essay quoted above, there is no mention to the original occupancy of the property first by Olive and Liz, and other Black activists throughout the 70s.

What follows are two accounts of the 121 Railton Road squat during the early 80s:

From: Bulleting of the Kate Sharpley Library

Number 121 Railton Road was a large corner building covering three stories plus cellar, it’s ground floor was formerly a shop. In the early days no real attempt was made to do anything with the building other than to hold meetings, parties and act as a hostel for the numerous comrades visiting the big smoke. As the number of anarchists in Brixton grew and contact was made with local anarchists (one of the big lies about the 121 anarchists was they were all outsiders) 121 was transformed into an almost 24 hour a day activity centre, housing a bookshop (admittedly running very erratic opening times but none the less it was to remain open for 10 years), a cafe and a disco in the cellar – the only place where one could be sure the floor would not cave-in.

From: Albert Meltzer – I couldn’t paint golden angels

When the Brixton riots began in 1981, the police did their best to blame anarchists, who had just squatted an empty shop at No. 121 Railton Road, and might otherwise have been the perfect patsy. It was rather difficult as the rioters were Black youths pushed by harassment, and few of them at that time knew what anarchism was about, certainly theoretically. The riots started in Railton Road, and 121 was left untouched when the pub that had operated a racist policy opposite was burned down, but it was the police who unwisely started a battle there, driving the battling youths out of Railton Road on to the main Brixton shopping centre.

Written by Ana Laura of the Remembering Olive Collective.

Comments

Cheers for this.. really

Cheers for this.. really interesting stuff..

Interesting stuff. 121

Interesting stuff.

121 Railton Road had a whole bunch of Direct Action Movement folks in it. I was there in 1984. It seemed like a pretty well kept place. The flat I was in was decent.

Had hot water and so forth.

I'm sure there's got to be a bunch of ex-121ers around.

i used to live a few doors

i used to live a few doors down from there, not at the time or owt, but people kept referring to this place. on urban75 (i know) there was an interesting thread about it. lms if i can find it. doubt it'll add any more knowledge to this thread though!

http://www.urban75.net/forums

http://www.urban75.net/forums/threads/railton-road-the-frontline-etc.125265/

(No subject)

[youtube]Egye9tBl-y8[/youtube]

Ha, ha! I was one of the

Ha, ha! I was one of the 'outsiders' - that was a long time ago

Urban75 has a small section

Urban75 has a small section on the whole history of 121 Railton Road:

http://www.urban75.org/brixton/features/121.html