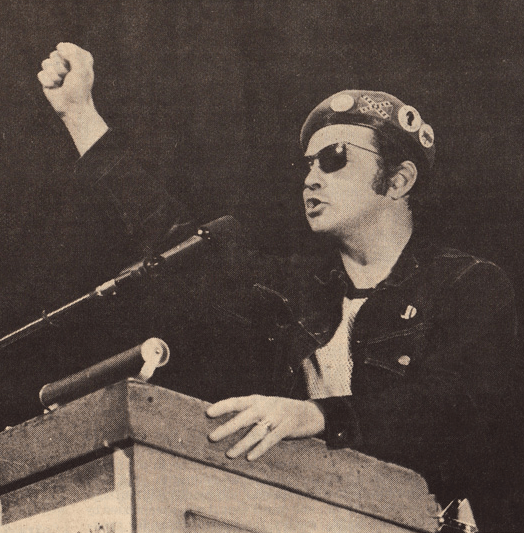

A speech by William "Preacherman" Fesperman at the 1969 anti-fascism conference held by the Black Panther Party in Oakland.

Content note: the below text includes offensive and racist language which has been reproduced in its original format as it was published in the Black Panther newspaper.

Introduction

The following speech was given by William “Preacherman” Fesperman at the United Front Against Fascism Conference held by the Black Panther Party in Oakland from July 18-21, 1969.1 Fesperman was the field secretary of the Young Patriots Organization (YPO) and a former theology student. The YPO was a Chicago-based group of poor, white, and revolutionary southern transplants. They played a crucial role in founding the original 1969 Rainbow Coalition, a groundbreaking alliance initiated by the Illinois chapter of the Black Panther Party, which also formally included the Puerto Rican street gang-turned-political organization, the Young Lords, and Rising Up Angry, another group that appealed to working class white youth. The Young Patriots are also, because of their explicit identification as “hillbilly nationalists” and symbolic adoption of the Confederate flag, one of the most fascinating, controversial, and understudied organizations to emerge from the intersection of the New Left student movement, civil rights movement, Black Power struggles, and new forms of community organizing that unfolded over the course of the 1960s in urban neighborhoods across the United States.

The lack of attention given to the group is understandable; with the exception of a two-page write-up included in the New Left collection The Movement Towards a New America, and a brief statement published at the end of the Black Panthers Speak anthology, very few writings from the YPO are easily available to the public.2 Moreover, until Amy Sonnie and James Tracy’s 2011 work Hillbilly Nationalists, Urban Race Rebels, and Black Power: Community Organizing in Radical Times, a timely study of radical and anti-racist activism during the 1960s and 70s within working class white communities in Chicago, Philadelphia, and New York, and Jakobi Williams’s recent book From the Bullet to the Ballot: The Illinois Chapter of the Black Panther Party and Racial Coalition Politics in Chicago, one of the only full accounts of the history of the Chicago Rainbow Coalition, very little in-depth historical care had been paid to the group.3 Republishing this vital archival text is a small attempt toward filling said void in the scholarship.

But just as important, we wager that, given renewed attention to racism, the legacies of the South, and the Confederate flag today, disentangling the visible contradictions of the YPO and analyzing their role as a key constituency of the Rainbow Coalition can help us demarcate certain positions within contemporary debates about radical history, organizing strategy, and political identity. In our current conjuncture, the idea of white and black radicals rallying side-by-side around cries of “Black Power to black people!” and “White Power to white people!,” as the Chicago Black Panthers and the Young Patriots did, seems absolutely unthinkable; but to dismiss this as mere anachronism would be to overlook a pivotal episode in American political activism and thus disregard what “strategic traces” and resources this experience could hold.4 To be able to investigate the YPO further, and understand how such a multiracial assemblage of groups like the Rainbow Coalition was possible in the first place, we should heed the advice of Cha-Cha Jimenez, leader of the Young Lords: “in order to understand [the Young Patriots], you have to understand the influence of nationalism.”5 This also requires us to chart the specific organizational forms and styles of political work that this nationalism assumed.

***

Formed in 1968, the YPO quite consciously took after the Panthers by combining revolutionary nationalism and community defense as a political strategy, and in their viewing of the “pig power structure” as a common enemy for both poor whites and African Americans. The YPO was also marked by the specific conditions of radical politics in Chicago where the “organize your own” activist model, famously advocated by SNCC in its later phase, meant not identity-based essentialism but a forging of connections across class, race, and ethnic lines. This is reflected in the YPO’s own 11-Point Program, which, while modeled on the original version put forth by the Oakland Panthers, contained a prominent addition. Following demands for full employment, better housing conditions, prisoners’ rights, and an end to racism, the Patriots also proclaimed that “revolutionary solidarity with all the oppressed peoples of this and all other countries and races defeats the divisions created by the narrow interests of cultural nationalism.” This principle of shared spheres of struggle and a division of political labor – a relative autonomy or independence at the community level – became driving features of the “rainbow politics” developed in Chicago.6 As opposed to the frustrations that many white radicals expressed concerning the new organizing model proposed by SNCC and other Black Power groups, the YPO and a broader network of community activists treated it as an opportunity for political experimentation from their own social position or frame: an opening to collectively think through the most effective strategies for united action and novel forms of solidarity politics, as well as the construction of participatory projects around the very real and specific problems facing southern migrants that wouldn’t be easily solved.

These initial considerations generate an obvious question: on what grounds could the Patriots see themselves as white revolutionary nationalists? How could they claim solidarity with the struggles being fought in the name of national liberation by oppressed groups at home and abroad? After all, the YPO’s student activist contemporaries in the Revolutionary Youth Movement (RYM) – a section of Students for a Democratic Society (SDS) which later split into the Weather Underground and a number of organizations in the New Communist Movement – took a radically different approach, theorizing whiteness as a “ruling-class social control formation” born of strategic alliances consolidated under the banner of white racial identity. Though these emerging tendencies agreed that whiteness conferred privileges on this sector of the working class, and that such benefits presented a serious obstacle to revolutionary class politics, they disagreed in their strategic assessments of how to proceed. The Weather Underground advocated for a complete divorce of white revolutionaries from the white working class. But the rest of RYM, rallied around the future leadership of the Sojourner Truth Organization, argued that the benefits bestowed by white supremacy ultimately proved to be a trap, a betrayal of any proletarians’ “real interests.”7 So how did the YPO arrive at and reconcile such a heterodox position?

The answer lies in the fact that the Patriots had a coherent regional identity around which to organize, and one with a history that often took on radical political valences: its membership was composed of southern migrants mainly from Appalachia, whose families had settled in the Uptown neighborhood of Chicago, a major hub along the northbound route dubbed the “hillbilly highway.” Historically, Appalachia has had a fraught relationship to other regions of the South, especially in terms of racial formation and ideological perspective; often, its inhabitants were marked as distinct from other white, Anglo-Saxon groups, and this produced combative expressions of both “national identity” – as “mountain people” – and at times, expressions of discontent against economic and state authorities and solidarity with other oppressed groups.8 In other words, there was a strong understanding of Appalachia as its own region of the South, and, because of its economic status as one of the most impoverished areas in the country, there was a general current of class resistance against the massive coal and power companies that monopolized whole towns and even counties (popularized in films like Matewan and Harlan County, USA). This went the other direction, too: for example, certain Marxist theorists arguing for black self-determination in the South, like Nelson Peery, saw poor Appalachian whites as a primary basis for unity with the white working class, and counted them as an “Anglo-American minority” in the “Negro nation.”9 In this reworking and unsettling of racial and national identity categories, common territory, language, culture, and post-Civil War labor forms became unifying aspects, rather than color.10

A document from the Southern Conference Educational Fund, a social justice and anti-racist organization led by Carl and Anne Braden, with a project-oriented approach patterned after SNCC, showed how far an understanding of the relations of oppression prevailing among poor white communities had progressed by the 1960s, with a practically anti-imperialist bent:

Appalachia is a colony, lying mostly in the Southern United States. Its wealth is owned by people who live elsewhere and who pay little or no local taxes… Like all colonies, Appalachia is run by men and women beholden to the absentee owners and the banks. Judges, sheriffs, tax assessors, prosecutors, and state officials are tied to the coal operators in one way or another. These people led the drive to stop union organizing in the mountains in the 20 and 30s, and they now lead the fight against organizing white and black people for political and economic power.11

Still, the composition of this “internal colony” had been changing for some time: between 1930 into the late 1960s, millions of southerners traveled to Northern industrial cities in search of work. Appalachia was especially transformed soon after WWII when a wave of automation and mechanization swept through the coal mining industries in West Virginia and Kentucky, leaving rampant unemployment and poverty in its wake.12 For those who left, the trip to the North did not ease these difficulties. Cities like Chicago and Detroit each faced their own problems: in the context of emergent processes of deindustrialization, work was often hard to find for many newcomers.13 Migrants faced scrutiny from state authorities, law enforcement, and other residents, with accusatory and sensationalist Chicago Tribune exposés labelling them as “one of the most dangerous and lawless elements of Chicago’s fast growing migrant population,” and police captains demanding they be expelled from the neighborhood.

Additionally, the housing situation in Uptown was deplorable. Single-room tenement houses were carved out of larger homes, with speculators and landlords paying little attention to real living conditions. Bob Lee, a Black Panther organizer who would be integral to formalizing the Rainbow Coalition, remembers these as “some of the worst slums imaginable,” even when compared to the African American-concentrated areas of the South Side; a Harper’s Magazine profile of Uptown was even more blunt, describing the neighborhood “as the most congested whirlpool of white poverty in the country.”14

The people who moved to Uptown did not leave everything behind, bringing their own cultural forms which were only reinforced due to the skepticism and outright prejudice they experienced. The area soon garnered comparisons to a “Hillbilly Harlem,” and the popular pastimes of Appalachia – pool halls, honky tonks, barbeques, country and bluegrass music – became points of community pride. Navigating this cultural landscape was vital to indigenous activists, and the young YPO organizers possessed a unique ability to draw upon the political potential and roots of these establishments and practices.15

This isn’t to say that a shared sense of resentment simmering among Uptown residents didn’t exist already: faced with discriminatory hiring practices and welfare policies, constant police harassment, and housing displacement through urban renewal projects, the southern migrant community in Chicago proved that even in purportedly homogeneous white communities, there were layers of stigmatization and processes of class stratification. As historian Jennifer Frost notes,

Whites, too, shared a consciousness based on whiteness, but the white identity of southern and Appalachian migrants in [Chicago and elsewhere] was complicated by class, as they were seen as “white trash” and “dumb hillbillies.” In fact, well before SDS arrived in Uptown, residents had carried signs declaring “hillbilly power” at a local protest. Community participants… did not think of themselves as “poor,” but “as a Negro who is poor or a Hillbilly who is poor.”16

Encounters with the existing political apparatus made it evident that municipal government was a limit, not a route, towards enhancing this power. As even the smallest attempts at changing local conditions could be blocked by the overwhelming forces of Mayor Richard Daley’s electoral machine, a new politics of community empowerment began to coalesce and constituted a specific but malleable organizational form and a range of insurgent practices that could connect issues of neighborhood improvement with better access to social services.17 Thus, a new front of struggle materialized, and offered unique opportunities for heightening the political capacities, awareness, and activity of grassroots forces.18

One of the vehicles for building this kind of community power in Uptown came, paradoxically, through the participation of outside student activists from SDS, albeit those from a different political milieu and ideological background than others who would go on to form the RYM theoretical current.19 These earlier members of SDS would help form the JOIN (Jobs or Income Now) Community Union in 1964, which was the Chicago chapter of SDS’s Economic Research Action Project (ERAP), one of the first large-scale community-organizing efforts of the New Left. The initial ideas for ERAP stemmed from the broadly Keynesian precepts shared by the first leaders and theorists of SDS, chiefly Tom Hayden, and its first strategic plans included organizing unemployed young men across the country, calling for full employment and/or guaranteed wages on a national scale, and, more generally, advocating democratic planning within the economic sphere. All these steps were intended to lay the groundwork for an “interracial movement of the poor.”

But activists soon discovered that such conceptions were more difficult to carry out in practice. They hit a wall trying to frame unemployment as a directly relatable issue. Where JOIN found greater success, however, was in engaging community concerns, or “immediate grievances”: welfare rights, housing issues, police brutality, to name a few. This shift towards addressing inadequate city and social services invited a high degree of skepticism from SDS members who wanted to keep pushing a national program, and they snidely nicknamed the new locally-focused approach GROIN (Garbage Removal or Income Now).20 In other words, many student leaders did not see any political content to these felt grievances.

Despite the pushback, the new strategic orientation, which responded to tangible social struggles on the ground, turned the Uptown Chicago JOIN initiative into a larger neighborhood-wide, and indeed city-wide, project. It was obvious that the political terrain had shifted, and that, to use Ira Katznelson’s terms, the “politics of community” could more successfully tap into already existing sources of political activism than the “politics of work” approach taken by ERAP.21 Following a broader trend, organizing issues proposed by community residents themselves – welfare rights, voter registration and education, public education issues, housing problems – opened up new possibilities for political awareness, especially following the often lackluster and highly restrictive implementation of many War on Poverty programs.22

Student organizers found indigenous leadership already present in Uptown, as some community members had direct experiences in the Civil Rights movement in the South and were ready to mobilize others around issues of racial discrimination. Support of black-led organizations and a consistent emphasis on anti-racist work were a key part of JOIN’s outlook and message, and the organization linked up with Martin Luther King’s first campaigns in 1966 to desegregate housing and schools in the city by participating in the Open Housing Marches (which encountered intense reactionary violence in the majority white suburbs). These new neighborhood-based activists included Peggy Terry, Rennie Davis, Dovie Thurman, Mary Hockenberry, and Jean Tepperman. Terry in particular became a highly respected community leader – a seasoned activist who took after Anne Braden, and a former member of CORE (and future vice-presidential candidate on a ticket with Eldridge Cleaver for the Peace and Freedom Party), Terry assumed a mentorship role for young members who would go on to join the Young Patriots Organization, not unlike Ella Baker’s relationship with members of SNCC.

Rent strikes and tenant occupations become effective tactics to leverage power against absentee landlords and indifferent housing boards. There was a proliferation of community-based projects: a JOIN community school was set up, where student organizers tried to tie problems in Uptown to national political and economic trends in discussion with residents. Student organizers and neighborhood activists formed a welfare committee, which contested rules around privacy, dispensation of funds, and aid revocation, and eventually won key protections for day laborers – a pressing question in Uptown. Terry also became the editor of a newspaper, The Firing Line, which relayed information about various Black Power movements, the war in Vietnam, and national liberation struggles abroad, including the struggle in Ireland.

While this encounter between student activists and neighborhood people eventually disintegrated in 1967 because of the failure of the ERAP project and demands from Uptown residents for greater autonomy, it also enabled more radical currents to emerge, including the Young Patriots. The roots of the YPO can be traced to the anti-police brutality committee of JOIN, founded in 1966. In fact, this work group was the Uptown Goodfellows, what Tracy and Sonnie describe as a “cross between a street gang and loose-knit radical social club.” Composed mainly of young men, these were also some of the most vocal critics of overbearing SDS involvement in JOIN. Members included Jimmy Curry, Doug Youngblood (the son of Peggy Terry) Junebug Boykin, and Hy Thurman, patient and skilled organizers all. Their central issue and focus was a salient one; police harassment was a ubiquitous, quotidian phenomenon in Uptown, and JOIN members had already set up an informal police watch and conducted several independent inquiries, with local help, into Uptown residents’ run-ins with police.

Like many youth gangs in Chicago of the period, including the Black Gangster Disciples and the Blackstone Rangers, the Goodfellows had an explicitly political message that went beyond turf skirmishes: to unite and coordinate with other local gangs, whatever their race or ethnicity, by fighting back against police harassment and intimidation – the most visible manifestation of the “real enemy,” i.e., corrupt politicians, capitalism, and the war. On this point, the Goodfellows bucked a dominant historical trend by openly aligning themselves with black or brown-led gangs and social organizations, since there is a long-established legacy in the United States of youth of color forming themselves into gangs as a measure of collective self-defense against violence and abuse carried out against them by not only the police, but by both white youth and white adult gangs.23

This nascent coalition-building came to fruition in August 1966 when, with the help of other JOIN activists, the Goodfellows organized a march with white, African American, and Puerto Rican youth on a local police station to protest police violence, ending with calls for community control of police. While the march proved that poor whites could play an active role in political organizing with other oppressed communities, it also helped to spark a wave of police attention towards the Goodfellows, foreshadowing the even more violent reaction that would befall the Rainbow Coalition.

The Patriots officially came together as an independent organization in 1968, with Boykin and Youngblood as de facto leaders. The YPO adopted the community concerns that JOIN confronted and reinforced their identity as southern migrants, or “dislocated hillbillies.” As Tracy and Sonnie put it, this was meant to be “an organization of, by and for poor whites.”24 Their identification as an oppressed community, however, was constructed through a militant opposition to capitalism and constant agitation against racism, a real problem in Uptown (Bob Lee notes that even with its legacy of activism, the neighborhood was a “prime recruiting ground for white supremacists”). The cultural spaces of Uptown – pool halls, street corners, bars – became spaces for political work, as the Patriots practiced a “pedagogy of the streets,” venturing out and meeting community members in familiar locations where they socialized and might be more likely to discuss their problems and ideas for change.25 And, again following the lead of both JOIN and the Panthers, a newspaper, The Patriot (with the subtitle: People’s News Service), was also regularly printed and distributed. After an influx of new members, including William Fesperman, the YPO soon made contact with the Panthers, and by the spring of 1969, the preconditions of the Rainbow Coalition were in place.

The first meetings between the Panthers and the Patriots in early 1969 had Lee, a core organizer in the Chicago Panthers, travelling to Uptown in order to meet and discuss shared experiences, demands, and goals. Things did not always go smoothly, and Fred Hampton, the leader of the Chicago Panthers, did not even immediately know about Lee’s trips to try and form an alliance. A critical juncture came, unsurprisingly, through a confrontation with the repressive arm of the state: one night after Lee left a meeting with the YPO, only to be immediately apprehended by police and herded into the back of a cop car. Witnessing this egregious instance of profiling and harassment, Fesperman gathered every person he could – not only other Young Patriot members but also their partners and children – to surround the car and force the police to release Lee on the spot. These minor battles and acts of solidarity reinforced the mutual respect the two organizations had for each other.

Some of the Panther/Patriot meetings were captured in the film American Revolution 2, showing Lee succinctly summing up the need for political unity between the groups: “there’s police brutality, there’s rats and roaches, there’s poverty up here, and that’s the first thing we can unite on.” Principles of revolutionary solidarity were linked to building an alliance between economically disadvantaged groups. For the Patriots and Panthers, “poor people’s power” was a form of class power. This meant taking matters into their own hands and reinventing tried and true tactics. At the end of the scene, a decision is made for several Uptown residents and Young Patriots to show up unannounced at an upcoming Model Cities meeting to voice their concerns about how government funds were distributed, and how many felt shut out of having any say in how the new antipoverty programs in Chicago were being managed, reprising a fundamental concern and strategy of JOIN.

Concrete demands would lay the basis for linking local bases of power together, that is, for constructing multiracial solidarity across poor, working-class communities in Chicago – among these southerners, Puerto Ricans, Chicanos, and African Americans. Other organizations in the Rainbow Coalition were won over by the YPO’s ability to put the guiding line of “serving the people” into practice, and the Lords, Panthers, and Patriots collaborated on several initiatives while also remaining focused on their own neighborhood work. Political education classes, a “Rainbow food program” that provided free breakfasts and meals to families around the Chicago area, and campaigns against urban renewal were just some of the collaborative projects that the Coalition members embarked upon. Housing and healthcare constituted the two of the most intense and protracted sites of struggle.

The YPO already had experience in anti-gentrification struggles; in 1968, Uptown community members, many of whom participated in JOIN, had fought against a proposal to direct federal funds towards the construction of a junior college, Truman College, in Uptown, which would displace thousands of southern migrant residents. In response, they proposed their own building plan for the area in question, accordingly named “Hank Williams Village.” This was to be a mixed-use community space modeled after the southern towns Uptown residents knew well, and was to contain accessible parks, day care centers, clinics, and enough housing to minimize displacement. The proposal was rejected, but delayed the opening of Truman College; the Young Patriots channeled this experience by participating, alongside the Young Lords and the Poor People’s Coalition, in a building occupation protesting a proposed expansion of McCormick Theological Seminary which would require the abolition of nearby low-income housing, much like the Truman proposal. This actually resulted in a victory, and the Patriots lent assistance to other building and land occupations, including some carried out by American Indian activists from Uptown’s sizable Native American population.

The network of free health clinics set up by the different Coalition groups was another admirable endeavor. Health politics and care access had always been a problem for poor communities, and Uptown was no different. Encounters with doctors and the healthcare system in general were often experienced as coercive and oppressive, and with the input of Terry, the Patriots strove to provide community health care by opening a free clinic that offered people some basic dignity. Staffed by activist doctors, the Patriots’ clinic was an impressive community-run solution that tried to demystify the medical experience for poor whites; it also, like the Panthers’ and Young Lords’ own clinics, came under constant surveillance from the Board of Health and law enforcement. There were numerous crackdowns, and soon mounting legal costs were enough to close the clinics down.

With these material and often novel practices of revolutionary solidarity, there came an accompanying political vocabulary, assembled and reworked from existing lexicons. The organizational form of the Coalition, as a multiracial front, meant that a shorthand color-coding system was put in place to denote its constituent elements. These were representatives of colonized communities, and their particular efforts toward self-determination contributed to the broader tapestry of revolutionary struggle, in the United States and abroad. Whence comes the roll-call of nods and overtures Fesperman gives to both homegrown and international figures of this struggle near the end of his speech: “Red Power to Sittin’ Bull, to Geronimo, Kathy Riteger in Uptown. And yellow power to Ho Chi Minh and Mao and the National Liberation Front. And Brown Power to Fidel and Che and the Young Lords and La Raza and Tijerina. And Black Power to the Black Panther Party.” The following line, however, is one that is quite discordant to our contemporary radical sensibilities, shows why some were hesitant to immediately ally themselves with the Patriots: “And white power to the Young Patriots and all other white revolutionaries.”

Of course, Fesperman did not advocate any form of white supremacy. Indeed, the phrase “white power” was a commonly heard expression in speeches by various members of the Illinois Panthers, even Hampton. In the specific context of the Rainbow Coalition, “white power” was simply “hillbilly power,” the particular form of revolutionary solidarity that poor whites contributed to the coalition with African Americans and Latinos, and who confronted similar economic and political conditions. The overarching political slogan of these groups was “All Power to the People,” with “the people” working as a binding or articulating category rather than a divisive one.26 These were codewords – crucial pieces of political jargon – for the practice of class struggle, as Lee and other veteran activists have reiterated. An Uptown resident and member of JOIN accurately captured this sentiment: “Just because we are poor, we should not have to live in slums and be pushed around because we are Puerto Rican, Mexican, hillbillies or colored.”27

Other features of the Patriots’ approach induced more deserved puzzlement and even anger, specifically their appearance: it’s well-known that the battle flag of the Confederacy was at first an integral part of the YPO’s image, both as a provocation to other groups on the Left and as a mode of popular outreach to other southerners. The raw shock effect of this usage could be jarring: photographs from the United Front Against Fascism conference show members of the Panthers’ security detail standing side-by-side with members of the Patriots dressed in denim jackets, Confederate flag patches stitched across their backs.

As the Patriots would themselves later recognize, this usage of the Southern Cross was a political error and deserving of thorough criticism. Still, the reasons behind the adoption of this emblem – a universal symbol of white supremacy, a real material reminder of the tortured history of racial violence and brutal after-effects of slavery in the United States – were related to an attempt to understand politically the racialization of the category of ‘hillbillies,” and therefore need to be considered in a nuanced fashion.

The Patriots’ appropriation of the rebel flag was related to a specific analysis of the Civil War as an intra-elite conflict: a “pissing match” or clash between a feudalistic, slave-holding southern planting class and Northern bourgeois industrialists, which then produced the civilizational divide between North and South.28 By using this symbolism, they were attempting to scramble the flag’s sedimented, accumulated meanings – a taking back of Southern history from below. Even as we disagree absolutely with the adoption of the particular symbol, the attempt to disrupt commonsensical assumptions about the clear-cut character of the Civil War (as an “incomplete bourgeois revolution,” for example) opens up avenues of historical inquiry. Appalachia especially was one of the most divided areas in the nation in terms of allegiances to the North and South due to the fact that it was not economically dependent on slavery and staple crops, and mountain partisans on both sides engaged in protracted guerilla tactics. Unionist and Confederate support varied almost county to county, and the war irrevocably altered kinship bonds and dynamics along class and community lines.29

As historians like Stephanie McCurry have shown, the Confederacy itself was rocked by profound insurgent movements from those it had politically dispossessed and disenfranchised: from poor white and yeoman women who triggered an intense wave of food riots in 1863, to the acts of slave resistance that commenced on Confederate plantations.30 Other recent scholarship has traced a complex network of collaboration between black people in the Appalachian highlands ‒ either settled freedmen, enslaved persons, or escaped slaves ‒ and Confederate deserters and escaped Union prisoners of war, who found safe havens in these remote mountain and borderland communities and shared resources and information.31 These instances of contentious politics within the Confederacy where black and white southerners struggled against oppression were the threads the Patriots sought to emphasize and rediscover.

In addition, the Patriots idolized John Brown and were well acquainted with Du Bois’s Black Reconstruction and Liston Pope’s Millhands and Preachers; all of these ideas and events were folded together in their broader view of a radical Southern history. Indeed, the Patriots were not the only ones to try and rework the meaning of the Confederate flag for social justice causes at the time: the Southern Student Organizing Committee, a group from Nashville inspired by SNCC, used a drawing of black and white hands superimposed over the Confederate flag as their logo in a bid to highlight their Southern orientation and roots.32 By this logic, the South’s “spirit of rebellion” represented by the flag was something to be proud of, but its real and discontinuous historical manifestations were those of poor people’s revolt and cross-racial solidarity.

By 1970, the flag symbol was dropped, on account that there was “no socialist justification for a revolutionary group using a symbol of counterrevolution.”33 The YPO underwent an organizational split, as well. Some members, like Youngblood, remained in Chicago and retained the Young Patriots name and would carry on doing local activist work together for a short time longer; others, including Fesperman, felt that the brutal police repression in Chicago, which had taken the lives of several Patriots members and, most famously, Fred Hampton, had taken too drastic of a turn, and that it was time to form a more national presence. The latter group rebranded itself as the Patriot Party and set up headquarters in New York City. While there was some initial success in opening several new Patriot chapters across the country, from Eugene, Oregon (which boasted a Free Lumber program) to upstate New York, it too ultimately dissolved under the pressures of state violence, investigative scrutiny, and mounting legal fees.

With current calls to rethink questions of solidarity work and multiracial coalition-building in the contemporary moment, a serious retrospective consideration of the Young Patriots and their political experience with the Rainbow Coalition – both their advances and missteps – might remind us of the ever-urgent need to articulate new languages and coordinate novel approaches within social movements. Poor rural whites still constitute a major target of the carceral state, and even with the major reorganizations in the relationships of race and class between black, brown, and white working class communities witnessed over the past few decades, the focus the Young Patriots put on the deleterious effects of brutal policing methods and the lack of control over federal service programs within their own social base, as an effective ground for strategic alliances, is as relevant as ever. As they put it themselves:

We’re sick and tired of certain people and groups telling us “there ain’t no such thing as poor and oppressed white people”… The so-called movement better begin to realize, that – first of all – we’re human beings, we’re real; second – we’ve always been here, we didn’t just materialize; and third – we’re not going away, even if you choose not to admit we exist.34

— Patrick King

You can read more about the history of the Young Patriots and the Original Rainbow Coalition here.

Young Patriots at the United Front Against Fascism Conference

Saturday, July 19, 1969

Listen here. I’m gonna say it. Turn off your tape recorders. Listen here, out there motherfucker. FREE HUEY.

We have a message from the people and the message from the people reads: “To you astro-pigs: ‘The moon belongs to the people.’”

We have another message to PL and that message reads, “PL, and Oakland City Council, Chicago City Council, and the government of the United States, all are paper pigs.”

Now, we have come from Chitown and we come from a monster. And the jaws of the monster in Chicago are grinding up the flesh and spitting out the blood of the poor and oppressed people, the blacks in the Southside, the Westside; the browns in the Northside; and the reds and the yellows; and yes, the whites – white oppressed people. You talk about have any white people before ever known what oppression is? Come to uptown Chicago. Five pig cars on a square block. White pigs murdering, brutalizing white brothers. Is it? Is it? Is it? We say, we talk to people a lot, and they say, “You hillbillies ain’t planning on picking up a gun or anything are ya? I mean, that one you brought from Kentucky, or North Carolina.” And we say to ‘em, “Listen here, why, you know, a gun ain’t nothing,” you know. A gun on the side of a pig means two things: it means racism and it means capitalism. And the gun on the side of a revolutionary, on the side of the people, means solidarity and socialism. Right on? Now, who in here and who out there is gonna let the motherfucker with the gun shootin’ capitalism and racism outshoot the people? Who’s gonna do it? Who is the racist dog? Let him walk up here and let me bite his head off. Let me get a hold of that son-of-a-bitch and you can beep it out if you want to. And Beep out Johnny Cash, you know, cause he tells the truth. When I get in front of McClellan, on behalf of the Southern people, on behalf of all people, I’m gonna bite his head off, and spit it in Nixon’s face.

Understand where we’re comin’ from when we talk about freein’ political prisoners. Because when we talk about that, we talking about concentration camps like Folsom Prison, San Quentin, Cook County Jail in Chicago and Statesville and we’re talking about the Chairman of the Black Panther Party in Illinois, my brother, who was sent down the river for 2 to 5 years for supposedly selling $71 worth of ice cream. Now, listen here, and I say this, see, because I think we have to deal straight, see and the judge who sent that brother is a nigger.

Free all political prisoners. We said to the city of Chicago, this is what we said to ‘em. Mayor Daley declared a war on gangs, you know, so we said, “We didn’t know any gangs fed 4,000 children a week.” And Mayor Daley’s talking about “feeding the hungry if we can find them.” And the people know they’re there because that’s the people. We stood up to lame-brained Daley, and we said, “Look here, man, you sent Chairman Fred off on 2 to 5 years and we got together, the Young Lords, the Young Patriots and the Black Panther Party in Illinois, we said, ‘Now what are we gonna do?’ We said, ‘We’re gonna intensify the struggle, motherfucker.’” We also said, “If Chairman Fred don’t get sent down the river, if I get blowed away, or if I don’t get blowed away, we still gonna intensify the struggle.” So, what did Mayor Daley do after shakin’ in his boots and oinkin’ right on, right on.

Now ya talk about fascism. I’ll tell you that since we all been in the Patriots the pigs don’t like it. You know that people being fed in uptown Chicago were the southern whites cause they don’t want to see any riot in a southern white ghetto. They don’t want to see that. You know, that’d wipe that moon shot off the front page, you know. Forget about that moon. It’s here.

Since we been in this thing, and really, we’ve been in it all our lives, coming from the South and comin’ from the damn coal mines, mill towns, and some of them down there ain’t even up to capitalism yet. They’re still back, way back to feudalism or something, you know. But, a Chicago pig, he has a loud oink, but let me tell you, you know, the people from the south, the white brothers and the black brothers, we’ve been to a lot of hog killings in our lives and I don’t know, but a lot of experience there and I think about ol’ Hammerhead Superpig Hoover. You know, he’s old, I don’t even want to eat them chitterlings out of that motherfucker. Fuck it.

Our struggle is beyond comprehension to me sometimes and I felt for a long time and other brothers in uptown felt that poor whites was (and maybe we felt wrongly, but we felt it) forgotten, and that certain places we walked there were certain organizations that nobody saw us until we met the Illinois Chapter of the Black Panther Party. “Let’s put that theory into practice about riddin’ ourselves of that racism.” You see, otherwise, otherwise to us, freeing political prisoners would be hypocrisy. That’s what it’d be. We want to stand by our brothers, dig? And, I don’t know, I’d even like to say something to church people, I think one of the brothers last night sad, “Jesus Christ was a bad motherfucker.” Man, we all don’t want to go that route, understand. He laid back and he said, “Put that fuckin’ nail right there man. That’s the people’s nail. I’m takin’ it.” But we’ve gone beyond it, and all we’ve got to say from the Young Patriots, where we come from, where we’re goin’ is to all of you, and thousands of others here and all over the world. All we got to say is, “All Power Belongs To The People.” Red Power to Sittin’ Bull, to Geronimo, Kathy Riteger in Uptown. And yellow power to Ho Chi Minh and Mao and the National Liberation Front. And Brown Power to Fidel and Che and the Young Lords and La Raza and Tijerina. And Black Power to the Black Panther Party. And white power to the Young Patriots and all other white revolutionaries. Whether the pigs or the pig power structure likes it or not, fuck it.

This speech was originally published in The Black Panther, Saturday, July 26th, 1969. page 8.

-

For more information on the UFAF conference and its immediate aftermath, see Joshua Bloom and Waldo E. Martin, Black Against Empire (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2013), 299-301. ↩

-

Barbara Joyce, “Young Patriots,” in The Movement Towards a New America: The Beginnings of a Long Revolution, ed. Mitchell Goodman (Philadelphia: Pilgrim Press, 1970), 547-548; The Patriot Party. “The Patriot Party Speaks to the Movement,” in The Black Panthers Speaks, ed. Philip S. Foner (Cambridge: Da Capo Press, 1995), 239-243. ↩

-

Amy Sonnie and James Tracy, Hillbilly Nationalists, Urban Race Rebels, and Black Power: Community Organizing in Radical Times (Brooklyn: Melville House, 2011); a condensed version of Sonnie’s and Tracy’s book can be found in James Tracy, “Rising Up: Poor, White, and Angry in the New Left,” in The Hidden 1970s: Histories of Radicalism, ed. Dan Berger (New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press, 2010), 214-230. More information on the Patriots can also be found in Gordon Keith Mantler, Power to the Poor: Black-Brown Coalition and the Fight for Economic Justice, 1960-1974 (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2013), 231-233 sqq. Mantler is critical about what he sees as the “contingent” nature of the Rainbow Coalition, as the organizations involved faced different problems according to their constituencies, neighborhoods, etc., and thus often had dissenting views on the primary fronts of struggle. The African American community in Chicago, for example, did not experience the same pressures stemming from urban renewal plans like the Puerto Rican and Appalachian populations did. While this is certainly a fair critique of idealized retrospective looks of the Coalition, a careful investigation of its internal composition, dynamics, and insurgent practices can function as a rebuttal against accounts, like those of James Miller and Sidney Tarrow, that see social movements in post-68, post-Democratic National Convention Chicago as following a dynamic that fragmented into “congeries of smaller single-issue movements.” See James Miller, Democracy is in the Streets; From Port Huron to the Siege of Chicago (New York: Simon and Schuster, 1987), 317, and Sidney Tarrow, Power in Movement: Social Movements and Contentious Politics (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1997), 150. ↩

-

I address this point in more detail below, but the political vocabulary that permeated the Chicago activist scene and the Rainbow Coalition was replete with these kinds of declarations. One of Fred Hampton’s most circulated speeches, “Power Anywhere There’s People,” contains one variant of this revolutionary nationalist language that emphasized the need for multiracial working class unity: ”That the masses are poor, that the masses belong to what you call the lower class, and when I talk about the masses, I’m talking about the white masses, I’m talking about the black masses, and the brown masses, and the yellow masses, too…We’re gonna fight racism with solidarity.” On the concept of “strategic traces,” see Bloom and Martin, op. cit., 20, 405, n.34. ↩

-

Sonnie and Tracy, 77. ↩

-

For more on this question of revolutionary solidarity and the Rainbow Coalition, see Johanna Fernández, “Denise Oliver and the Young Lords: Stretching the Political Boundaries of Struggle,” in Want to Start a Revolution? Radical Women in the Black Freedom Struggle, eds. Dayo F. Gore, Jeanne Theoharis, and Komozi Woodard (New York: NYU Press, 2009), 271-293. ↩

-

For a richer historical account of these debates see Michael Staudenmaier, Truth and Revolution: A History of the Sojourner Truth Organization 1969-1986 (Oakland: AK Press, 2012). The most important texts in this debate were collected by Paul Saba, ed. The Debate Within SDS: RYM II vs. Weathermen (Detroit: Radical Education Project, 1969). The quotations originate from one essay in that collection: Noel Ignatin’s [Ignatiev] “Without a Science of Navigation We Cannot Sail the Stormy Seas, or Sooner or Later One of Us Must Know.” ↩

-

The classic account of Appalachia as an idea and discourse remains Henry D. Shapiro, Appalachia on Our Mind: the Southern Mountains and Mountaineers in the American Consciousness, 1870-1920 (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1978). For interesting explorations of the roles of poor whites had both in forms of slave control but also slave resistance, and the fears that these potential alliances stirred among the ruling classes, see John Inscoe, “Race and Racism in Nineteenth-Century Southern Appalachia: Myths, Realities and Ambiguities,” in Appalachia in the Making, eds. Mary Beth Pudup, Dwight B. Billings, and Altina L. Waller (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1995), 103-131; Jeff Forret, Race Relations at the Margins: Slaves and Poor Whites in the Antebellum Southern Countryside (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 2006), 115-156; also cf. Herbert Aptheker, American Negro Slave Revolts (New York: Columbia University Press, 1943), 360-367. ↩

-

See Nelson Peery, The Negro National-Colonial Question (Chicago. Workers Press, 1978). ↩

-

For more on this point, see Robin D.G. Kelley and Betty Esch, “Black Like Mao: Red China and Black Revolution,” Souls 1 (Fall 1999), 6-41, 27. ↩

-

Southern Conference Educational Fund pamphlet, in The Movement Towards a New America: The Beginnings of a Long Revolution, ed. Mitchell Goodman (Philadelphia: Pilgrim Press, 1970), 261-262. For an similarly interesting, if dated, take on this internal colony analysis for Appalachia that more explicitly incorporates insights from dependency theory and theorists of decolonization, see Keith Dix, “Appalachia: Third World Pillage,” Antipode 5.1 (March 1973), 25-30, which summarizes some of the work done by the People’s Appalachia Research Collective and their journal, People’s Appalachia. ↩

-

SDS did make some inroads organizing in Appalachia with the Economic Action and Research Project, explained below. The balance sheets written by veteran activists of their successes and failures in the poverty-stricken mining community of Hazard, Kentucky, remain essential documents to revisit: see Hamish Sinclair, “Hazard, Ky.: Document of the Struggle,” Radical America 11.1 (January-February 1968), 1-24, and Peter Wiley, “The Hazard Project: Socialism and Community Organizing” in the same issue, 25-37. The SCEF set up its own project along the same lines, the Southern Mountain Project, with a special emphasis on connecting the issues of working-class rights to the continuing struggles of African-Americans, or as they put it: “helping some of the poorest people in America build on the experiences of the Southern freedom movement to organize for political and economic power.” On this and the legacy of the Bradens, see Catherine Fosl, Subversive Southerner: Anne Braden and the Struggle for Racial Justice in the Cold War South (Lexington: University of Kentucky Press, 2006). ↩

-

On this other “Great Migration” of poor whites to the North and Midwest, see Jacqueline Jones, The Dispossessed: America’s Underclasses from the Civil War to the Present (New York: Basic Books, 1992), and Chad Berry , Southern Migrants, Northern Exiles (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2000). ↩

-

Sonnie and Tracy, op. cit., 21. An early, oral history-focused survey of the transformation of Uptown, conducted by two SDS organizers, is Todd Gitlin and Nancy Hollander, Uptown: Poor Whites in Chicago (New York: Harper Colophon, 1971). A more recent and culturally oriented study can found in Roger Guy, Diversity in Unity: Southern and Appalachian Migrants in Uptown Chicago, 1950-1970 (Lanham, MD: Lexington Books, 2007). ↩

-

Indigenous is used here both in terms of an approach to studying social movements “from below,” as popularized by Aldon Morris in his The Origins of the Civil Rights Movement: Black Communities Organizing For Change (New York: Free Press, 1984), and to signal the problem of forming leadership from the constituents or members of dominated or oppressed communities, through a participatory process of activism that raises their sense of political understanding and awareness. For more on this term, its broadly Gramscian connotations, and its currency in the Civil Rights movement through figures like Ella Baker, see Barbara Ransby, Ella Baker & The Black Freedom Movement: A Radical Democratic Vision (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2003), 273-298, 357-374. For some problems in how this ideal has played itself out in protest movements before, during, and after the 60s, see Francesca Polleta, Democracy is an Endless Meeting: Freedom in American Social Movements (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2002). ↩

-

Jennifer Frost, An Interracial Movement of the Poor (New York: NYU Press, 2005), 114-115. ↩

-

Besides Frost, two major resources for the history of community organizing in the United States are Wini Breines, Community Organization in the New Left, 1962-1968 (New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press, 1989), and Robert Fisher, Let the People Decide: Neighborhood Organizing in America (New York: Twayne Publishers, 1994). Also Alyosha Goldstein’s recent book, Poverty in Common: The Politics of Community Action During the American Century (Durham: Duke University Press, 2012). ↩

-

Rhonda Y. Williams, Concrete Demands: The Search For Black Power in the 20th Century (London: Routledge, 2014); cf. Peniel Joseph, “Community Organizing, Grassroots Politics, and Neighborhood Rebels: Local Struggles for Black Power in America,” introduction to Neighborhood Rebels: Black Power at the Local Level, ed. Peniel Joseph (New York: Palgrave, 2010), 1-19. ↩

-

On ideological shifts within SDS, see Kirkpatrick Sale, SDS: The Rise and Development of the Students for a Democratic Society (New York: Random House, 1973). ↩

-

A sober reflective account of these strategic revisions is Richard Rothstein, “ERAP: Evolution of the Organizers,” Radical America 2.2 (May-June 1968), 1-18. See also his “Short History of ERAP,”available at the SDS documents archive. ↩

-

Ira Katznelson, City Trenches: Urban Politics and the Patterning of Class in the United States (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1981), 24-26. ↩

-

For comparable processes and events in Oakland, which provided the immediate context for the rise and decline of the Black Panther Party there, see Robert O . Self, American Babylon: Race and the Struggle for Postwar Oakland (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2003). The classic account of these concerns in 1960s activism, especially the problem of organization-building through individual and collective grievances, which touches upon the same problematic encountered by ERAP and JOIN, remains Frances Fox Piven and Richard Cloward, Poor People’s Movements: Why They Succeed, How They Fail (New York: Vintage, 1979), especially 284-288, 296-308. ↩

-

I owe this point to discussions with Delio Vasquez and his unpublished paper “Criminalized Politics and Politicized Crime: Illegal Black Resistance in the 1960s and 70s,” delivered at the UC-Santa Cruz Friday Forum for Graduate Research, February 13th, 2015. ↩

-

Sonnie and Tracy, op. cit., 72. ↩

-

The phrase is Sonnie and Tracy’s, but points to a real definitional problem in how we conceptualize the boundaries of political work and processes of political education. ↩

-

See Ernesto Laclau, On Populist Reason (New York: Verso, 2005), 67-128. ↩

-

Frost, 116. ↩

-

Sonnie and Tracy, 76. More extensive analyses of the Civil War existed on the New Left, and would flourish in the New Communist Movement, with Theodore Allen and Noel Ignatiev’s formative account, mentioned above, of white-skin privilege within the history of the United States labor movement, “The White Blindspot” and Ignatiev’s “Black Worker, White Worker,” being among the more robust. For a recent pathbreaking Marxist analysis of the causes and effects of the Civil War, and its connection to the history of forms of social labor in the United States, see Charles Post, The American Road to Capitalism (Leiden: Brill, 2011). ↩

-

See The Civil War in Appalachia: Collected Essays, ed. Kenneth W. Noe and Shannon H. Wilson (Knoxville: University of Tennessee Press, 1997); Wilma Dunaway, Slavery in the American Mountain South (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2003). ↩

-

Cf. Stephanie McCurry, Confederate Reckoning: Power and Politics in the Civil War South (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2010); for the author’s concise synopsis of her research, see Stephanie McCurry, “Reckoning with the Confederacy,” South Atlantic Quarterly 112.3 (Summer 2013), 481-488. ↩

-

Cf. John C. Inscoe, “‘Moving Through Deserter Country’: Fugitive Accounts of the Inner Civil War in Southern Appalachia,” in Noe and Wilson, ed., op. cit., 158-186; also Steven Hahn, A Nation Under Our Feet: Black Political Struggles in the Rural South from Slavery to the Great Migration (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2003). ↩

-

Gregg L. Michel. Struggle for a Better South: The Southern Student Organizing Committee, 1964–1969 (New York: Palgrave Macmillan. 2005), 50, 247, n.47. ↩

-

A passage from an article in The Patriot newspaper from 1970. Thanks to Hy Thurman and Ethan Young for the reference. ↩

-

The Patriot Party, op. cit., 239. Amiri Baraka made this argument in remarkably similar terms four years later, in his “Toward Ideological Clarity”: “If we continue to act as if whites do not exist in this society, we will be left trying to build a fantasy world in which the skin brotherhood will be the answer to all problems rather than political consciousness.” This position paper was published in Black World, November 1974, 91. ↩

Taken from https://www.viewpointmag.com/2015/08/10/young-patriots-at-the-united-front-against-fascism-conference/

Comments