A selection of texts in memory of Nanni Balestrini, the Italian autonomist writer who passed away in May 2019. Originally published by Blackout, and re-shared by Enough Is Enough.

Contents:

• Extracts from We Want Everything

• Nanni Balestrini and the Poetry of the Italian Autonomia

• Extracts from Blackout

• Extracts from Carbonia (We Were All Communists)

• On Nanni Balestrini, the Most Radically Formalist Poet of the Italian Scene

Selections from We Want Everything, Balestrini's novel of struggles at Fiat and Italy's "hot autumn".

THE STRUGGLE

These guys I’d talked to about the struggle couldn’t accept it, they didn’t know what the fuck to do. They didn’t understand what I was proposing. They felt somehow that what I was proposing was right, but they didn’t know how to act on it. They didn’t understand that the important thing was to stir things up all together. I got pissed off. Not because I would get fired for what I had done, because they already wanted to fire me anyway, they were just looking for an excuse. I’d been at Fiat for three months and I couldn’t stand it any more. I couldn’t hack it any more as an employee, as a worker. It was May, it was already warming up and I wanted to go back down south and go to the beach.

I didn’t get pissed off because I was going to get fired. That was certain, but I didn’t give a shit about that. They could easily pick me out as I was. I had a moustache, I wore white shoes and a blue shirt, blue pants, it was easy to pick me out. And I stayed how I was when I entered the the workshop, without getting changed, without taking my old shoes, my old pants, my old pullover out of my locker, without getting changed the way you always did. I’d gone in wearing what I wore out in the street, with polished white shoes, everything spot-on. I had gone into the workshop like that, committed to not working. But I was pissed off because I hadn’t managed to convince the others.

I feel like getting a Coke from the machine and I drink it and arrive late to the assembly line. You always have to arrive before the line starts, never after. I found my foreman, and the other foreman, already there, and everyone looking at me. And the leading hand was at my post. I get there and the boss says: Look, you’re breaking everybody’s balls. You have to come on time; I’m giving you a half-hour penalty. I tell him: Do whatever the fuck you want, you’re really breaking my balls, you and Fiat. Go get fucked before I fling something at your head. You can stick these filthy fucking machines, I don’t give a shit.

All the workers who were standing around were looking at me and I said to them: You’re a bunch of assholes, you’re just slaves. You should be getting into these guards here, these fascists. What the fuck are these insects, let’s spit in their faces, let’s do whatever we want, this is like military service. Outside we have to pay if we go into a bar, we have to pay on the tram, we have to pay for a pensione or a hotel, we have to pay for everything.

And inside here they want to tell us what to do. For a few useless pennies, good for fuck-all, for work that kills us and that’s it. We’re crazy. This is a life of shit, people in prison are freer than us, chained to these disgusting machines so that we can’t even move, with the screws all around us. The only thing missing is a whipping.

Anyway I started to work, reluctantly, because I wanted to fight. I wanted to do something, staying there wasn’t for me. While I was there I heard shouting in the distance. The body workshops are huge sheds, so big you can’t see to the end, there’s a constant noise and you can’t hear human speech. The workers have to shout to be heard. I heard trouble, shouting, and I said to myself: It’s the comrades starting a demonstration. I didn’t know where it was, you couldn’t see. I abandon my post, cross all the lines, I cut across them, where all the other machines are, and I go to the comrades. I get there and I join in the shouting, too. We were shouting the strangest things, things that had fuck-all to do with anything, to create a moment of rupture: Mao Tsetung, Ho Chi Minh, Potere operaio. Things that had no connection to anything there but that we liked the sound of.

Things like Long Live Gigi Riva, Long Live Cagliari, Long Live Pussy we shouted. We wanted to shout things that had nothing to do with Fiat, with all that we had to do in there. So everyone, people who had no idea who Mao or Ho Chi Minh was, were shouting Mao and Ho Chi Minh. Because it had fuck-all to do with Fiat, it was OK. And we started to organise a march, there were about eighty of us. And one by one as the march passed through the lines people joined on at the back. We found some cartons and tore them up and wrote on them with chalk: Comrades leave the lines your place is with us. On another one we wrote: Potere operaio. On yet another: To arselickers work, to workers the struggle. And we went marching on with these signs.

The march got bigger and the union officials arrived. It was the first time in my life I had seen union officials inside Fiat. The officials start up: Comrades, there’s no need to fight now. We’ll take up the struggle in autumn with the rest of the working class, with all the other metalworkers. Now means weakening the struggle, if we fight now how will we fight in October? We tell them: We need to fight now because it’s still spring and the summer is ahead of us. In October we’ll need overcoats and shoes, we’ll need to pay for the central heating in our apartments, schoolbooks for our children. So the worker can’t fight in autumn, he has to fight in summer. In summer he can sleep in the open air if he has to, but not in winter. And you know that Fiat needs more product in spring, if we stop now we’ll mess up Fiat, but in October they won’t give a shit.

The union officials got us into little groups, to divide us up, to break up the march. About twenty of us start another march somewhere else and get some comrades back. In two hours we manage to stop all the lines. Right at that moment the boss of the body plant arrived, the colonel. We were in workshop 54, but all the lines had stopped because we’d gone into the other workshops and we’d made them all stop. The colonel arrives, and as he comes a space opens up among the workers, everyone suddenly goes back to the lines. Fifteen of us were left alone there with signs. So I decide that this is the right moment to confront him, because if not we were pissing everything away.

He comes towards us and I go towards him with the sign right in his face. I plant it half a metre from his nose and he reads it. I don’t remember which sign it was, something was written on it, I didn’t care what. The only thing I cared about was for him to go get fucked. Make him understand that he couldn’t do anything to us. He sees that I wasn’t going anywhere, that I’d planted myself right there in front of him, and he says: So what are all these signs? Price tags for vegetables? Is this the market? No, I say, they’re signs against the bosses, that’s why we made them. Then he gets a little group of people together, the engineer of the body plant with the other workers. And around the engineer were five hundred workers who kept nodding yes, yes. He spoke and they nodded yes. The union officials gathered other groups on the other body plant lines, and we were left in a little group of fifteen isolated comrades.

So I say: Comrades, we need to act because if we don’t they’ll isolate us, they’ll screw us. We have to intervene where the engineer is speaking because he’s the biggest fish. If we can fuck up the engineer in front of the workers, we’ll save everything. If we can smash the capitalistic management of this little group we’re there, we’ve won the struggle here today. We went over to them, the engineer was speaking and I say: Can I join this discussion too? He goes: Please, speak. What do you have to say? I have only one thing to say: What productivity bonus do you get? That’s none of your business, goes the engineer.

No, in fact it is my business. It’s my business because the maximum productivity bonus we get … I don’t even know how much I get. I never look at what’s on my pay slip, my base salary, piece rates, insurance and all of that. I just take the money, without reading it, because I’m not interested in reading it, I’m only interested in the money. But for sure we’d get five or six per cent at the most, maybe seven per cent. But how much do you get? It’s none of your business. In respect of the tiny percentage that we get, I continued, you, according to the annual production of automobiles, which we make, get a bonus of millions of lire. That’s why it’s in your interests to make us more and more productive. While for us, the work and the money never change. Is that true or not?

I repeat, it’s none of your business. How is it not my business? With my work you make millions and then you say it’s none of my business. You make money because the productivity bonus increases with increases in your category. Whether you’re a leading hand, a foreman, a big boss, Agnelli. The biggest bonus, clearly, is Agnelli’s. I turned towards the workers: Do you know how much money this guy takes in production bonuses? Do you know why he doesn’t want to tell me?

Then the colonel steps in and says: But don’t you know that I’ve studied? That I’m an engineer? No, I don’t know that, I answer. And I say: But do you know that we don’t give a shit whether you’ve studied? That we don’t recognise any authority over us other than our own any more? He says: Didn’t your parents teach you anything? No, they didn’t, did yours? Yes, mine did. And then he says, Have you done your military service? No, I haven’t done my military service, why, what’s my family and my military service got to do with it? What it has to do with it is that your family should teach you how to behave, to respect people who are more educated. And if you had done military service you would understand that there is always a hierarchy that must be respected. Whoever doesn’t respect this hierarchy is an anarchist, a criminal, crazy.

You could say that I’m crazy, but there is also the fact that I don’t like work. There, there it is, he shouts, you’ve all heard it, all of you, people who strike don’t like work. And so, I say, why do these guys prefer standing and talking to you over getting onto the lines? You can see that none of these people like work either. Anything, any excuse is enough, even standing and listening to someone talk. Workers don’t like work, workers are forced to work. I’m not here at Fiat because I like Fiat, because there isn’t a single fucking thing about Fiat that I like, I don’t like the cars that we make, I don’t like the foremen, I don’t like you. I’m here at Fiat because I need money.

As I see it you won’t be here for much longer, the colonel says. I hear that a security guard was beaten up outside. If I find out who did it, I will make him pay dearly. You don’t have to go far to find out who it was, I say. I’ve never liked riddles very much. I know you’ll make me pay, but I really don’t give a shit. I gave that guy a beating and I’ll give someone else a beating tonight. The guy caught the sniff of a beating and got himself out from among us workers quick smart. The fifteen of us had lined up in front of him, and behind him were all the other workers. He runs off, but first he says to me: What is your name? I tell him my name, my surname, the name of my foreman, that I’m in workshop 54, on the 500 line, and that I’m always available. I tell him all this to show that I’m not afraid of him. You’ll see, I’ll make you pay. Ah, get fucked, get out of here you fucking prick, you’ll make me pay some other time.

He goes off, and as he goes all the workers: ehhhhhhhhh, a shout, everybody cheering: You’re a legend, you fucked him up all right, that guy’s a real prick, he wanted to make fools out of us. OK, OK, I say, we’ve done that, but now it’s time to march. We have to fuck things up for good, smash everything in here now. And we kicked our boots against the cartons of supplies, making a sullen, violent noise, dududu dududu, a couple of hours of this uproar. Now and again we’d have a sort of meeting, one time at the north end of the lines, then at the south. We wound our way through them shouting all together: More money less work. Vogliamo tutto: we want everything. We climbed up and down the lines and held more meetings.

On like that until the evening. When evening came I went to punch my time card. My time card wasn’t there, they’d taken it away. I go to the supervisor. Boss, where’s my time card? He says: Isn’t it there? Don’t mess around, where have you put it? I reply. I don’t know where it is, he goes, if it’s not there it means you’ll have to wait and then we’ll see. OK, I’ll wait then. Anyway, all the workers head off, they all leave. It was just me, it seemed, at Mirafiori. While I wait another foreman turns up, then another, and another. I say to myself: Hey, this smells like security guards. Boss, where’s my time card? You have to come to the office, he goes.

Like fuck I’m coming to the office. I’m coming into the factory again tomorrow, with or without my time card. But I’m not coming to the office. If the colonel has something to say to me he can come and say it here in the workshop. I haven’t got anything to say to him, it’s him who wants to say something to me. And I took off quickly so I wouldn’t be the last one there. Some workers were coming out of the locker rooms where they’d showered and dressed. I catch up with my workmates and say: Comrades, they want to grab me and report me. They’ll grab me at the gate and slip some bit of junk into my pocket and call the police and report me for theft. That’s how they do it.

All arranged. They’d grab me, put any old bit of metal in my pocket, a bolt or a spanner. They’d call the police: we caught him stealing, and this morning he beat up a security guard. They’d give me three years. This was their scheme. They wanted to get me at any cost. I went ahead with the comrades. Let’s stay on our toes at the gate. Because at the gate a guard picks you out, makes you go into a room and pokes around in your bag and your clothes. If they pick me out now, I say to the comrades, I’m not going in for the search, because if I go in I’m fucked. We go on, we get to the gate and I see the foreman, my foreman, surrounded by guards, five of them. The foreman goes: It’s him, that one there.

A guard comes forward, he’d be the head-kicker in this situation, and says: You, actually, You, please, because they’re always formal at Fiat, You, please, come with me. Who, me? Why do I have to come? Come with me please. I don’t want to come. Please come with me. I don’t want to come, what do you want with me? Why, have you never been searched before? Yes, but this afternoon I don’t feel like it, and I haven’t got a bag, look, I’m wearing a pullover. I lifted it to show my bare chest. I’m wearing pants, that’s all, I haven’t got anything on me, can’t you see? Ciao. Come here, he yells.

He grabs me around the neck, this fucking goon, and drags me along. So I think about what the fuck to do for a moment. I pretend to go with him. Then I put a foot in front of him and give him a shoulder in the back. Punft, he falls to the ground like a cow turd. I give him a kick in the balls. Two other guards jump me. The first one holds me by the legs and these other two on top. I kick them and elbow them and manage to throw them off. Then I’m beside them with my head down because the monster is holding me tight. At this point another comrade pulls on the arm that this asshole has around my neck like a vice. I pull his arm away, jump up, spit in the animal’s face. And run. Then they grab the other comrade, and they fired him, because he helped me.

And I left. I went out and there were loads of workers and students outside. Outside the gates all the comrades were talking about the struggle. There were comrades who said I’d done the right thing by fighting the guards. That the day had been a great struggle, really satisfying. And we had a meeting right then. A huge mass of workers went to the bar, so many that you couldn’t get in. And there I met Emilio and Adriano and a load of other comrades. That evening a whole lot of us decided to hold a demo at the university. And that was the beginning of the big struggle at Fiat. That was May 29, a Thursday.

THE WAGE

[…]

But the workers’ only objectives are their economic and material needs, what they need to live, and they don’t give a shit about the bosses’ needs, about the productivity that decides the degree to which those needs are satisfied. So it’s clear that the political problem is to attack all the tools of political control that the boss holds and that he uses to bind the working class and force us to serve his productive ends and to take part in our own exploitation. The workers’ weapon for fighting this tool is the refusal of the wage as compensation for the quantity and quality of work. It is therefore the refusal of the link between the wage and production. It’s the demand for a wage that is no longer fixed by production for the bosses, but by the material needs of the workers. That is: Equal increases in the base wage for everyone. Material incentives such as piece rates, categories and so on are only the worker participating in his own exploitation.

And who has the pimp’s job of negotiating with the bosses for a few more lire for the worker in exchange for new tools of political control? It’s the union. And it then becomes itself a tool of political control over the working class. Fighting for its economic and therefore political objectives, the working class always ends up clashing with the union. Because when workers no longer want to give the boss more political control in return for an economic increase, then the union that has the pimp’s role of negotiating this exchange is put out of the game by the workers.

From here therefore the working-class need for a guaranteed wage not linked to productivity. From here the working-class need for increases in base pay without waiting for contract negotiations. From here the working-class need for a 40-hour week, 36 for shift workers, paid at 48 now. From here the working-class need for parity in the awards now. For the simple act of going into the factory hell: We want a guaranteed minimum wage of 120,000 lire a month:

Because we need this money to live in this shitty society. Because we no longer want the piece rates to have us by the throat. Because we want to eliminate the divisions between workers invented by the boss. Because we want to be united so we can fight better. Because then we can more easily refuse the boss’s hours. Because more money in base pay means a greater possibility of struggle. We want 40 hours, 36 for shift workers, paid at 48 now:

Because we don’t want to spend half our lives in a factory. Because work is bad for you. Because we want more time to organise ourselves politically. We want the same regulations for blue-collar and white-collar workers now:

Because we want a month’s holidays. Because we want to carry out the struggle against the boss as workers and technicians together. Because we want to stay at home without losing our whole wage when we just can’t work any more.

THE COMRADES

As I came out of the Fiat gate after I’d escaped the clutches of the guards, I couldn’t wait to find the other comrades, either the comrades I’d been in the struggle with inside or the students who I’d made and handed out leaflets with at the entrance. I thought about things while I was heading to the bar to meet up with the comrades. Things I had thought about at other times, but this time I felt I was coming to the full conclusion.

I’d had all kinds of work in my life. Construction worker, porter, dishwasher in a restaurant, I’d been a labourer and a student, which is also a job. I’d worked at Alemagna, at Magneti Marelli, at Ideal Standard. And now I’d been at Fiat, at this Fiat that was a myth, because of all the money that they said you made there. And I had really understood something. That with work you could only live, and live poorly, as a worker, as someone who is exploited. The free time in your day is taken away, and all of your energy. You eat poorly. You are forced to get up at an impossible hour, depending on which section you’re in or what work you do. I understood that work is exploitation and nothing more.

Now this myth of Fiat was ending. I’d seen that a job at Fiat was the same as a construction job, the same as washing dishes. And I’d discovered that there was no difference between a construction worker and a metalworker, between a metalworker and a porter, between a porter and a student. The rules the teachers applied in those technical schools and the rules the bosses applied in all the factories where I had been were the same. So this posed a great problem for me. That is, I thought, what do I do now? What do I do, what do I have to do?

I hadn’t stolen yet, I’d never had a gun. I’d never been friendly with the so-called low-life. At least I would have had an outlet, whether for feeling pissed-off, for my dissatisfaction, or for my needs, my material life. I wasn’t a doctor or a lawyer, a professional. So it wasn’t as if I could say, OK, I’ll become a thief or a freelancer. I was really nothing; I couldn’t do a thing.

Yet I had this desire to live, to do something. Because I was young and blood was coursing through my veins. The pressure was pretty high, in other words. I wanted to do something. I was ready for anything. But it was clear that for me anything no longer meant worker. This was already a dirty word. It meant almost nothing to me. It meant to keep living the shitty life I had lived up to that moment. What did I care about work, which I had never liked and had never cared about? And what was I supposed to make of work if it didn’t even bring me enough money to get by comfortably? Now I understood everything, I had experimented with all the possible ways of living. First I wanted to be inside, then I understood that inside the system I would always have to pay. For whatever kind of life, there was always a price to pay.

Whatever you want to do, if you want to buy a car or a suit, you have to work extra, you have to do overtime. You can’t have a coffee or go to the movies. In a system, a world where the scope is only to work and produce goods. Anything you want to get from this system you have to put back. But really, physically, from yourself. I’d understood this. So the only way to get everything, to satisfy your needs and desires without destroying yourself, was to destroy this system of work for the bosses as it functioned. And above all to destroy it here at Fiat, in this huge factory, with so many workers. This is capital’s weak link, because if Fiat stops, everything else goes into crisis, everything blows up.

I got to the bar and found lots of comrades waiting for me. We all embraced, celebrating what we’d done. All Mirafiori had stopped, even the 500 lines. Production had stopped completely on the second shift. Even though the union had shut down the struggle in Maintenance, with laughable results. One by one the others arrived, the students arrived, other workers I had never seen who had been in the struggle arrived. Everyone spoke and it was decided that the strike should continue tomorrow.

Even the workers from the big automatic lathes wanted to try to strike the next day. They decide that workers from the second shift would wait in the factory for workers from the third shift, and the third shift would wait for the first. They say they want to march in the factory to shut down other workshops. Workers from the Mechanical lines want to strike for the whole shift. There is a long discussion. It’s decided to let the strike go ahead for the first shift tomorrow, from 7.30 until 11. The demands: refusal of the schedules, refusal of categories, large wage increases, the same for everyone. We want less work and more money, we write in large print on the leaflet that is made to hand out tomorrow at the gates.

And I finally had the satisfaction of discovering that the things I had thought for years, the whole time I’d worked, the things that I believed only I thought, everyone thought, and that we were really all the same. What difference was there between me and another worker? What difference could there be? Maybe he was heavier, taller or shorter, wore a different coloured suit, or I don’t know what.

But the thing that wasn’t different was our will, our logic, our discovery that work is the only enemy, the only sickness. It was the hate that we all felt for work and the bosses who made us do it. That’s why we were all so pissed off, that’s why when we weren’t on strike we were all on sick leave, to escape that prison where they took away our freedom and our strength, day after day. I finally saw that what I had thought on my own for a long time was what everyone thought and said. And I saw that my own struggle against work was a struggle we could all have together and win.

Sometimes you don’t understand each other and you don’t agree because one person is used to thinking one way and someone else in a different way. One person like a Christian, another like a lumpenproletarian, another like a bourgeois. But in the end, in the fact of having been in a struggle together, we were able to speak the same language, to find that we all had the same needs. And these needs made us all equal in the struggle, because we all had to struggle for the same things. The meeting was fantastic, it stirred us up. Everyone recounted what had happened on the line. Because nobody could know everything that happened in that factory, where there are twenty thousand workers just in the body plant.

As if anyone could know everything that happened. The supervisors, the workers, what they said, what they did during the struggle. Recounting everything like this, we discovered a series of things. The organisation was being created, the comrades said, it’s the one thing we needed to win the struggles. And as soon as a comrade spoke about what had happened on his line, how he had convinced the others to take part in a march, in the strike, in a meeting; as he explained these things, right away I found this comrade, who I had never even seen before, familiar. He became like someone I had always known. He became like a brother, I don’t know how to say it. He became a comrade. You discover, here’s a comrade, someone who has done the same things as me. And the only way to understand that we all think in the same way is to do the same things.

At the end of the meeting a leaflet was worked out, and how to carry on the action the next day. The comrades advised me not to go into the factory because they would arrest me. They even said I shouldn’t go home because the police might come, and a comrade took me to stay at his place. And I really liked this, because it was the help we all offered each other in the struggle, it was our organisation. And in fact the next day I phoned my sister and she said the police had been there that evening looking for me. My mother wrote to me from home saying the Carabinieri were asking after me in Salerno. They went to my sister’s house three or four more times.

Fiat had filed a complaint for injuries to the guard. I went to the doctor at the insurance agency and got him to give me a medical certificate for ten days because I had a scratch the guard had given me. I put myself on sick leave. Then after a week I went to get paid out, unannounced. Because I still had my Fiat ID card I could get into the factory. And as I get to my work station, on the line, my supervisor comes up to me with two guards and says: You have to come with me to the office.

I look at my line, where I was standing. There wasn’t a single comrade, not one; I was alone. And I didn’t know whether to put my hands up, what the fuck to do, I had no idea. I go to the office, and they make me wait there for the colonel, the Engineer. And while I’m waiting, I take the Fiat ID card from my pocket and put it right in the middle of the Engineer’s desk. Because it was the Fiat ID card that they wanted, to stop me coming into the factory. After a moment the Engineer comes in and says: Ah, that’s exactly what I wanted, you understand. I’m sitting there, spread out on a sofa, but he doesn’t say a thing.

Another guard comes in, a huge gorilla, and goes: What are you doing sitting there? Huh. I’m sitting down because I’m tired. You have to get up. I don’t feel like standing up, if you want, get me up yourself. You think you’re strong, he goes, coming towards me. I don’t think I’m anything, it’s just I don’t feel like it, it’s a pain in the arse. Anyway, he says, you’re lucky I wasn’t outside the other night. If I’d been there I would have given you something. I know, you would have killed me, but you weren’t there, so calm down. It was a fascist-type provocation, to get me into a fight, so they could give it to me and then report me, call the police and finally put me away.

I didn’t fall for it, because in there I would have really copped it, they would have killed me. I signed the papers that they brought, my resignation and all that crap. And when I went out there were twenty, actually twenty, guards outside the door to the office expecting a brawl. They escort me to the locker room, I get my things, and they escort me right out of the place. A month later I went to the building where the insurance agency was with the slip to get my money. As for the complaint they filed against me, I never heard what became of it. There must have been some kind of amnesty or something.

In the morning I woke up at the house of the comrade where I’d gone to stay, then we went to the student’s place. There was a meeting there with a load of comrades. The leaflet that had been mimeographed during the night was handed out and we went down to the factory. Big groups of people formed and the comrades who were going in said even they were being stopped. The workers who were going in already knew what the aims of our struggle were, the struggle for equal things for everyone that had been carried on up to then. The workers didn’t value the work they did at all, they didn’t feel like they were second or third category, they all felt the same, exploited. For the first time workers were fighting to all get the same pay. To have the right to the same working conditions as the clerical workers. Equal pay rises for everyone, the same category for everyone: they were excited by these things, which united them.

And that’s how it was then, every day. Early in the morning we went to hand out leaflets at the gates, or the weekly newspaper of the struggle, which was called La Classe. There were all these leaflets and these newspapers from the struggle. Then you slept for a while, then you went back to the gates at one-thirty or two to hand out leaflets when the second shift went in. And you waited for the first shift to come out, for meetings with the guys from the first shift. You went again in the evening around eleven to wait for the workers from the second shift to come out and you got together with them, you had meetings. The gates of Mirafiori were like a street market in those days. Everyone was there, unionists, PCI, Marxist-Leninist kids from the Unione20 dressed in red, police dressed in green, all competing with the hawkers who waited for the workers with fruit and vegetables, T-shirts and transistor radios. Everyone promoting their goods.

In truth the PCI, which hadn’t been in the struggle, only came after July 3 to explain that the proletarians who had been beaten were just irresponsible, mercenary provocateurs. They were the same workers who the bourgeois courts later convicted. They came to explain that struggles decided and carried out by the workers autonomously were dangerous because they allow the bosses to resort to repression. They came to accuse us of being no more than little groups who were estranged from the factory, but they didn’t explain how such miserable little groups could carry on a struggle as long and as powerful as the struggle of those months.

Unionists, PCI bureaucrats, fake Marxist-Leninists, cops and fascists all have one characteristic in common. They have a total fear of the workers’ struggle, of the workers’ ability to tell the bosses and the bosses’ servants to go to hell and to organise their struggle autonomously, in the factory and outside the factory. We made them a leaflet that finished like this: Someone once said that even whales have lice. The class struggle is a whale, and cops, Party and union bureaucrats, fascists and fake revolutionaries are its lice.

[…]

The struggle went on for more than two months, a brutally spontaneous struggle. There wasn’t a day when some section, some workshop, wasn’t shut down. Every week, more or less, all of Fiat was shut down. They really were days of continual struggle. In fact the masthead of the leaflets that were made was Lotta Continua,21 and really, at Fiat in Torino in those months there was a continuous struggle. We wanted to prevent work at any cost, we didn’t want to work any more. We tried to send production into crisis for good. To bring the bosses to their knees and force them to come down and negotiate with us. We were fighting a battle to the end.

By now one thing was obvious in these meetings: all the workers understood that it was an important phase in the fight between us and the bosses, a decisive phase. You could feel the consciousness in the air. And the word revolution was said often in meetings. You saw comrades who were in their forties, who had families, who’d worked in Germany, who’d worked on building sites. People who’d had every kind of job, who already said that by sixty they’d be dead from work.

It’s not fair, living this shitty life, the workers said in meetings, in groups at the gates. All the stuff, all the wealth that we make is ours. Enough. We can’t stand it any more, we can’t just be stuff too, goods to be sold. Vogliamo tutto — We want everything. All the wealth, all the power, and no work. What does work mean to us. They’d had it up to here, they wanted to fight not because of work, not because the boss is bad, but because the boss and work exist. In a word, the desire for power started to grow. It started for everyone, for workers with three or four children, unmarried workers, workers who had kids to put through school, workers who didn’t have their own apartment. All our unbounded needs came out in concrete aims during the meetings. So the struggle wasn’t just a struggle in the factory. Because Fiat has one hundred and fifty thousand workers. It was a huge struggle not just because it involved this great mass of workers.

Because the content of these struggles, the things the workers wanted, weren’t the things that the unions said: the work rates are too high, let’s lower the rates. Work is harmful, let’s try to remove the harm, all this bullshit. They didn’t want to be part of it any more. They discovered, the workers, that they wanted power outside. OK, in the factory we manage to fight, to hold up production when we want. But outside what do we do. Outside we have to pay rent, we have to eat. We have all of these needs. They discovered that they didn’t have any power, the State fucked them over at every level. Outside the factory they didn’t become citizens like all the other workers when they took off their overalls. They were another race. In this system of continuous exploitation they were workers outside as well. To live as workers outside too, to be exploited as workers outside too.

These leaflets that were made, which came out of the meetings, the workers took these leaflets home. Showed them to friends who worked on building sites or other places, and so they ended up all over the place. They often went to distribute them in the neighbourhoods, too, like at Nichelino: in fact, at Nichelino there was an occupation of the town hall over housing that went on for quite a few days. They said the rents were too high, they couldn’t afford them. A leaflet was made that said: Rent — theft of salary. And they didn’t pay any more. Some comrades from the PCI took part in the occupation, and then they left, after which the PCI did everything it could to disrupt the occupation of the town hall.

Nichelino is a working-class dormitory on the outskirts of Torino. Out of 15,000 people, 12,000 are workers, of whom 1700 work in Nichelino, 5500 at Fiat in the various plants at Carmagnola, Rivalta, Mirafiori, Airasca, Spa Stura and so on, the others in factories spread mostly throughout the Fiat cycle, for example Aspera Frigo, Carello and lots of others spread all over.

Around there a family’s budget was the following: wages at a factory in Nichelino for 8 hours work varied between 60,000 and 80,000 a month. Rent — don’t even think about 10,000 — varies from 20,000 to 35,000, plus 2,000, maybe 4,000 costs and central heating. That leaves between 30,000 and 50,000 for living, so that working hours have to rise to 10 or 14. Someone who works at Fiat will never get ahead at all. The cost of travel and the unpaid commuting time, at least two hours a day, uses up the rest.

Characteristics of the dwellings at Nichelino: More or less complete absence of services. Rents continually rising. Constant blackmail by the landlords, with the threat of eviction. Real difficulty for big families, particularly from the south, finding housing. During the 13-day occupation of the town hall, flyers posted on the walls told day by day of the development of the struggle at Fiat and brought the whole population into the discussion at the occupied town hall. Committees of struggle were formed in more factories with claims the same as at Mirafiori. The problems of the factory were connected to the problems outside the factory, the objectives unified the struggles.

These concrete material objectives of the struggle got right around the city, because they were things that concerned everybody, that touched everyone directly. This is what caused the explosion on July 3, the huge battle between the proletariat and the State and its police gangs. That great battle, July 3, is easily explained, because everybody on the streets and in the neighbourhoods understood immediately why those workers were demonstrating, why they were fighting the police. They weren’t demonstrating just because they were radicals and had to have a demonstration. No, it was a fight for proletarian aims, the same as they’d been fighting for weeks inside Mirafiori and now it had spilled out onto Corso Traiano. For objectives that everyone had known about for weeks. Education, books, transport, housing, all of these things. The things that always fucked up the money you earned in the factory.

And they knew it would never be because of union strikes, because of the reforms that the unions asked for, that the State would graciously concede. And even if it did concede it would be all on its own terms. Never, with these strikes, with these reforms. Things always had to be taken, by force. Because they’d had it up to here with the State that always fucked them up and they wanted to attack it, because that was the real enemy, the one to destroy. Because they knew that they could have somewhere to live, that their needs could be satisfied, only if they swept away the State, that republic founded on forced labour, once and for all. That’s how the great battle can be explained, not because people were pissed off by the heat on July 3.“

AUTONOMY

[…]

Wednesday 18 June: At six in the morning the workers on the first shift at workshop 54 returning to the factory learn what had happened the day before, about the great struggle their comrades in the second shift had continued and even widened. Yesterday the strike stuttered along, they say, today we’ll hit like an avalanche. And that’s how it goes. From one assembly line, the 124, only a single vehicle exits, from another, three or four cars. The 500 lines, after going along at a reduced rate themselves, stop completely. Both shifts are now on strike, all the lines stopped. At 1.30pm the workers from the first shift leave the factory with fists raised. And they are greeted with the same salute by the workers of the second shift who are re-entering the factory and who started the strike at Mirafiori.

The workers from the second shift continue the strike, solid. Fiat tries to make them work by running the lines empty. But after a short time it becomes clear even to the bosses that the workers are making fun of this move and the lines stop. A march starts from workshop 54 and disrupts workshops 52, 53, 55, 56. Not a single vehicle leaves the lines all afternoon. With the strike on the assembly lines completely under the workers’ control, the march heads towards the management building. They meet the union delegates there, who try to deny everything that they have said against the strike in the past few days. They are no longer heard. The march moves towards the gates, where it blocks the truck exit. And finally it re-enters the lines, where a number of workers step up to speak to the meetings that are gathering all around.

Thursday 19 June: Comrade workers of Rivalta, yesterday in workshop 72 the workers suspended work for an hour. The request for uniforms was only a pretext, the reality is that the workers were protesting against exploitation and the brutish conditions inside and outside the factory. Inside because the bosses continue to up the work rates, making the work more and more unbearable. With work rates that make you spit blood without even time to eat or go to the can. Outside because the starvation wages are no longer enough to pay higher and higher rents and don’t allow workers even the bare essentials of life. So workers are forced to live eight to a room or sleep on benches at the station. That’s it, Fiat’s workers are starved of money and want to work less.

Rivalta is at the most advanced point of technological development, the model of automation, the boss’s jewel. All the special vehicle assembly lines have been transferred here. The 128 and the 130, the latest Fiat models, are built here. Today Fiat uses Rivalta to make up the increasingly bad losses caused by the struggle at Mirafiori, at least in part. They try to squeeze the workers, asking for production increases every day, pushing to the limit of the workers’ resistance. The 128 line produces four extra vehicles a day. But workshop 72 signalled the beginning of the struggle. The bosses tried to pre-empt it, generously conceding some categories because they are scared that the struggle at Mirafiori will become the struggle at all of Fiat. And we know that all of Fiat in the struggle means beating the boss with objectives chosen and organised by the workers, workshop by workshop.

Friday 20 June: Comrade workers, for the fourth day the second shift in the body workshop has held up all production. The workers’ marches have blocked every attempt to restart work. The first shift has also continued the struggle. On Wednesday only 30 vehicles came off out of more than 400 in normal production before the struggle. Production was drastically reduced yesterday as well. But this is not enough. The workers on the first shift must be as strong as their comrades on the second shift. Every variation in the consistency with which the struggle develops allows the bosses and their thugs to turn us against one another. To destroy every danger at its source there is only one response, unity in the struggle.

All output must be blocked. In the past month we have discovered that we have extraordinary strength. Only one workshop has to stop to hold up the whole factory. The organisation is growing and connecting up all the workshops, allowing the full use of this formidable weapon. This means that if the task of carrying the struggle forward today belongs to workshop 54, painting and polishing, other workshops must be ready to relieve them and must do so as soon as possible without waiting for the struggle in 54 to burn out. Today many workers intend to support the comrades of workshop 54, who are carrying the whole weight of the struggle, with donations. It’s right but it is not enough. We must prepare ourselves to take our place in the struggle in all the workshops. We must meet with the workers of workshop 54 right away and coordinate the strikes. In this way the struggle will never be stopped again.

Today the union officials, who can’t move freely outside the gates, have the boss’s permission to hand out leaflets in the factory and spread false rumours. Here’s what the union wants to say in the factory. Yesterday they told us that they had won 12 lire. But we have demanded: 50 lire on the base wage for everyone, advancement through the categories for everyone, breaks for everyone, without making up production.

Workshop 85 continues the struggle. Yesterday the Rivalta workers went into action and stopped the 128 line. Our action has been joined for two days by electronic control and data systems technicians. It is a powerful movement. That’s what scares the radio and the newspapers, from La Stampa, which is silent or says little, to L’Unita, which spreads lies. To connect with each other, keep ourselves informed, discuss and direct the development of the struggle, meeting of all workers on Saturday 21 June at 4pm at Palazzo Nuovo in the University.

Saturday 21 June: At Mirafiori, as well as workshops 54, 85, 13 in the struggle, workshops 25 and 33 are also starting. Stop works at Rivalta. There have also been stoppages at Lingotto that point to a much wider struggle. At Spa Stura workshops 29 and 25 staged stop works for two hours all week. At Mirafiori workers from the other lines must substitute for those from 54 who were taking up the fight. Wherever claims have been made, there is no need to accept the bosses’ constant stalling but to go right out on strike. In the Mechanical workshops many are saying it is not a good time to fight because Fiat has built up big stocks. But the strike would damage production at Rivalta and Lingotto.

Monday 23 June: Workers of 85, for a week we of 85 have been fighting in the way that we believe is best for us and most harmful to Agnelli with very precise claims: second category for everyone, the same as the comrades of 54. The lines have gone back to work for now but we will carry on with our claim for second category for everyone. As long as the lines are not held up they ignore our claims. Now they have extended the offer from six to seventy categories. They are trying to divide us in this as well by buying some of us off with promises. Let it be clear that we do not intend to negotiate our claim. Yesterday they even tried to make seconded hands work; they’re nothing but scabs, and we responded accordingly. At South we ran them off. At North we completely stopped work, jamming up the lines from 9pm until 11pm. We should all remember: la lotta continua. It’s either second category for everyone or we’ll fill the piazzas.

Tuesday 24 June: Workshop 25 is completely at a standstill, all three shifts on strike for eight hours. Our warning to the managers: Pressuring us to unload the ovens is useless, reminding us of the value of the parts in the ovens is useless. It’s your fault if you had them loaded because you knew the workers on the first shift intended to strike. But you didn’t believe in our strength and so the strike has taken you by surprise. If you want to keep the Foundry working and want to avoid losses now you have to pay. The threatening letters you gave the workers on the first shift are a provocation that doesn’t scare anyone. Workers of 25: now we have the upper hand. Our strike has direct consequences for all Fiat production. Yesterday after just eight hours of strikes the Mechanical workshop was already in trouble. Now they will start to run short of parts for Rivalta, Spa Stura and Autobianchi in Milano. We will continue the struggle.

[…]

THE ASSEMBLY

[…]

But there’s one thing. Outside I met a union official, here at the university, and a few guys pulled me away, because I wanted to argue over what I told him: I want to meet, you and me. You’re from the union, OK. We put forward our conditions, fifty lire. But, he said, when you went on strike all together, you didn’t call me. But there was no need to call you because we can do things for ourselves. You’ve made a mistake, says he. But now, these twelve dismissals, what’s to be done? Then he said he didn’t know. I’ll tell you what’s to be done. You’re from the union, so call all the workers at Fiat to go on strike and the rest all together. Because if there’s another dismissal, what, will you get the strike going? Or how will it be done? He didn’t answer.

Then I said, if at a certain point I take responsibility for the struggle, for my whole workshop, then all the other workshops have to join the strike with us. I went to 24 to ask them to be part of the strike. They said: No, because the PSIUP is imposing it on us. This fucking PSIUP is giving me the shits. However you look at it, it’s like this: if those of us who were dismissed don’t go into the factory, the workshop where I am, at least, won’t go to work. Prolonged applause. Comrades, if signor Agnelli takes it on himself to dismiss ten, tomorrow he won’t dismiss ten but five hundred. He’ll dismiss a thousand, two thousand and kick us all out. But he is not the boss. We, the workers, are. While we in the factory earn a hundred thousand lire a month, signor Agnelli earns two hundred billion with our blood, it’s us who spill blood. Let’s strike inside and out, let’s strike. Applause.

[…]

Comrades, earlier I heard about comrade Emilio, who got a beating. I heard the day before from a fascist who works with my wife that signor Agnelli offered thousands for the fascists to provoke any of the groups gathered near the gates. I thought it was just talk, but knowing that they gave Emilio a beating, I think this is happening. We know they gave Emilio a beating and they’ll give others beatings. But the best thing is this, that Agnelli has finished using his tactics, his so-called modern and democratic tactics. In the past he had the unions as his lackeys but now they’ve bombed completely. They’re not there now, they don’t know what to do, they’re no use to him any more.

Now he’s trying to get tough, which is capital’s last resort. I mean, when you take a hit, at first you try to play fair. Then when he sees that he can’t take it he rounds up the various action squads. Well, he’ll get it too. What happens, happens. We reply to Agnelli that it is not so much our struggles that strengthen our will, but he himself who has shown us that he’s on the ropes. So I say this, whatever he does now he can’t break the workers’ will. He can’t kid himself, he already knows it very well. Workers are developing another mindset, they understand what they have to do. Maybe only a few, maybe a vanguard, but that is the important thing. I don’t speak from others’ experience. In four years I have changed completely, before I had what you might call a petit bourgeois mindset, I believed that by being good you would get everything.

Today I am, let’s say, a revolutionary. They call us that, or cinesi,25 they don’t even know themselves. Anyway, I wanted to say, there will be provocations at the march, but we will march all the same. I say no one can stop us now. And there’s another thing: we don’t criticise the Communist Party just for the sake of criticising it. It’s logical that the revolution won’t happen tomorrow or the day after, but I do say this: the worker’s mindset is too advanced now and the Party is trying to hold it back. It’s logical that we need to take one step at a time, but ultimately, when there’s the base, when there’s the mass pushing from below, that says everything is a mess, in a disruptive manner, the Party keeps holding back, and the union too.

And they keep saying: an apolitical union, as a comrade pointed out earlier. But I reply. Are you taking the piss? Do you really think we’re still morons who believe that the union can possibly be apolitical? But that’s how completely fucked they are now. They’re mercenaries, and they’ll be treated like mercenaries. So carry on like that, you unionists. Take the bosses’ money, your time will come. Then see, we’ll make you a nice casket. Applause. Agnelli is on the ropes, capitalism in its phase of development is on the ropes, all our enemies are on the ropes. So we’ll continue the struggle and we will never stop, never. Let Agnelli and all his worms be warned. Long applause.

[…]

But what the fuck do we care if workers in Russia are exploited too, if they are exploited by the socialist state instead of the capitalist boss. It means that is not the type of communism that works. And in fact it seems to me that they think more about production and about going to the moon than the people’s wellbeing. Because wellbeing comes before everything else in allowing us to work less. And that is why now we say no to the terrified bosses when they ask us to help them with their production, when they explain to us that we have to take part, that it is in all our interests, too.

We say no to the reforms that the unions and the party want us to fight for. Because we understand that those reforms only improve the system that the bosses exploit us with. Why should we care about being exploited more, with a few more apartments, a few more medicines and a few more kids at school. All of this only advances the State, advances the general interest, advances development. But our aims are against development, they’re against the general interest, they’re ours and that’s it. Our aims, the interests of the working class, are the mortal enemy of capital and its interests.

We started this great struggle by demanding more money and less work. Now we know that this is a call that turns everything upside-down, that sends all the bosses’ projects, capital’s entire plan, up in smoke. And now we must move from the struggle for wages to the struggle for power. Comrades, let us refuse work. We want all the power, we want all the wealth. It will be a long struggle, years, with successes and setbacks, with defeats and advances. But this is the struggle that we have to start now, a violent fight to the end. We must fight to end work. We must fight for the violent destruction of capital. We must fight against a State founded on work. We say: yes to working-class violence.

[…]

So now we say it’s time to end it, because they don’t know what to do with all this enormous wealth that we produce in the world other than waste it and destroy it. They waste it making thousands of atomic bombs or going to the moon. They destroy fruit, peaches and pears by the ton, because there’s too much and it isn’t worth anything. Because for them everything must have a price, it’s the only thing they care about, products without value can’t exist as far as they’re concerned. It can’t just be for people who don’t have food, according to them. But with all the wealth that exists people don’t need to die of hunger any more, they don’t have to work any more. So we’ll take the wealth, we’ll take everything.

Are we all going mad? The bosses who make us work like dogs destroy the wealth we’ve produced. But it’s time to be done with these people. It’s time for us to fuck these pigs off once and for all, to get rid of them all and free ourselves for ever. Listen, State and bosses, it’s war, it’s a struggle to the end. Forward, comrades forward like at Battipaglia, let’s burn everything here, let’s sweep this lowlife away, let’s sweep this republic away. Very long applause.

THE INSURRECTION

[…]

But what the police hadn’t thought about, what the commissioner hadn’t thought about, what the interior minister hadn’t thought about, what Agnelli hadn’t thought about, was that you weren’t dealing with the usual student march, the so-called march of extremists. Or as the bourgeois newspapers said, the usual rich kids who have fun playing at revolution.

The workers who met outside Mirafiori gate 2 were the same workers who had been fighting at Fiat for all those weeks. They were workers who had been in hard struggles, victorious struggles. While the start of the march was being organised, the police began their manoeuvres. To one side they set a double cordon of Carabinieri who linked arms and pushed the demonstrators back. Other platoons of Carabinieri lined up in fours and advanced slowly into the middle of the demonstrators.

While deputy commissioner Voria gave these orders, moving the Carabinieri to surround us, he told a worker to move away from him. But this worker threw a punch that laid him out flat on the ground. Meanwhile the platoons of Carabinieri who were manoeuvring came on at a trot, jogging like Bersaglieri, right into the middle of the demonstrators. And they were holding their rifles like cudgels, like clubs. Suddenly the charge sounded, which naturally no one fucking heard.

Then the teargas started to land, a dense mist of teargas, and everyone instinctively ran. Everyone ran and the Carabinieri began cracking us all with their rifle butts. They pushed us against the cordon of Carabinieri who held fast to surround us. I was right next to the cordon, their faces were pale, white, green with terror. Because they found themselves so close to us, face to face. A little while before I’d wound one up, I told him: Just wait, I’ll take your pistol and shoot you with it. He didn’t say a word.

They grabbed a comrade and wanted to drag him off, but they couldn’t because we pulled him away and threatened them. Meanwhile with the sudden mist of teargas they dispersed the crowd around Mirafiori. We all ran away from the front of Mirafiori, and then the Carabinieri who had formed the cordon took their rifles, which they’d had on their shoulder straps, in their hands like club“s and came after us. It was a nice little massacre, they belted us madly with their rifle butts. Then they arrested about ten comrades. Just because we were there, without sticks, without stones. While I’m running I come upon a load of Carabinieri, ten of them, beating the shit out of a comrade who was stretched out on the ground. I yelled at one of them: What the fuck, do you want to kill him?

The guy gives me a dirty look, then he turns and takes off with the others, dragging this comrade along behind them. Then while I was there, about three or four metres away I saw a comrade, a student who was running with four or five Carabinieri after him. One catches him, and he smashes him in the head with his rifle, cracks his skull. I run over with some other guys and the Carabinieri take off. We get this comrade who’s on the ground out cold and carry him away. We leave him with some women who were standing in a doorway. Because by now everyone from the surrounding buildings had come down into the street or out on their balconies, women, kids and babies, to see what was going on.

They had more or less managed to disperse us, but they hadn’t reckoned with the workers’ will to fight. Ten thousand people gathered between Corso Agnelli and Corso Unione Sovietica. There were tram tracks there with cobblestones between them. They start to fly at the police and the Carabinieri. And so they started to take a few hits, too. We got the march going that they had stopped at first. A policeman had been disarmed, his shield and helmet were taken off him and raised like trophies. There were banners that said: Potere operaio, and: La lotta continua. Suddenly a police ambulance sped into the middle of the march. It charged into the middle of the march with its siren wailing for no reason. Then it turned back the other way slowly. It was another provocation by the police. But the march starts and turns towards Corso Traiano.

[…]

We got into this park, and the police came with their wagons and the Carabinieri with their trucks. The Carabinieri copped a barrage of stones, because they were out in the open and it was easy to hit them. We came right up to the trucks to attack them with sticks, and they threatened to fire on us with their machine-guns, and we stopped. So they took off. The police in armoured vans heard this constant din, the heavy rain of stones falling on their vans, and there’s no way they wanted to get out. We’d surrounded all the vehicles, hurling stones from all sides. As soon as they got out we would have beaten the shit out of them with the sticks. We even tried to overturn a couple of the vans. The guys inside, terrified, told the drivers to get out of there, and in fact they took off, the lot of them.

A quarter of an hour later they tried again, coming into the park on foot. With shields, helmets, batons, rifles with teargas grenades. We were waiting for them in the park. They came to within fifteen or twenty metres of us. We started to taunt them, saying: Why don’t you try to get us now, like you did outside gate 2? We’ll fuck you up good. Only one of them answered: Come out on your own, we’ll go man to man, I’ll fuck you right up I will and so on. But they didn’t move, they were scared.

[…]

There were red flags on some of the barricades; on one there was a sign that said: Che cosa vogliamo: tutto. People kept coming from all around. You could hear a hollow noise, continuous, the drumbeat of stones rhythmically striking the electricity pylons. They made this sound, hollow, striking, continuous. The police couldn’t surround and search the whole area, full of building sites, workshops, public housing, fields. People kept attacking, the whole population was fighting. Groups reorganised themselves, attacked at one point, scattered, came back to attack somewhere else. But now the thing that moved them more than rage was joy. The joy of finally being strong. Of discovering that your needs, your struggle, were everyone’s needs, everyone’s struggle.

They were feeling their strength, feeling that there was a popular explosion all over the city. They were really feeling this unity, this force. So every rock that was hurled at the police was hurled with joy, not rage. Because in a word we were all strong. And we felt that this was the only way to defeat our enemy, striking him directly with sticks and stones. The neon signs and the billboards were battered. The traffic lights and all the poles were smashed and pulled down. Barricades went up everywhere, with all kinds of things. An overturned steamroller, burnt electricity generators. When darkness fell you saw fires everywhere among the teargas fumes, molotov cocktails flying, flames.

I couldn’t get into the middle of the fighting with the police. Loads of comrades had got there before me, coming from all over. You couldn’t see for smoke and there was noise and confusion. The police were quickly pushed back towards the end of Corso Traiano with lots of us chasing them. We faced off with the police and fought at the edge of the park. There was one policeman on the ground, who moved now and again. A load of our guys chased the police across the tram tracks and a huge cloud of black smoke rose from the burning cars. Our guys swirled all around, you saw them go into the smoke and come out and you heard lots of explosions.

Everything was confused, people yelling and running back and forth. When we got near the end of the street it looked like the clashes had already been going on for a while. We came across a comrade bleeding from his mouth and we hoisted him onto our shoulders. Further on we came across another comrade who was bleeding and couldn’t stay on his feet. He kept getting up and falling over again. When we got right near the end we could see the police. They had got out of the vans and were standing in a group with their helmets and their shields.

They were waiting for us and firing teargas. We had just about surrounded them, from every side. I could hear some of our guys shouting: Get out of here. And I saw that lots of police-men were scared and were running away. All around our guys started to chant: Ho Chi Min. Forward, forward. They rushed forward and the air grew dark with dust and smoke. I saw bodies moving around me like shadows and the noise of explosions, sirens and shouting was really loud. At one point I saw a policeman right in front of me and I got into him with a stick. The policeman fell under foot as everyone ran.

At the end we turned back down the road and there were loads of injured people there, too. We’d cleared the police right away. We were all crazy with happiness. We waited there a bit longer and after a while we saw a line of trucks coming from one of the cross streets. Everyone began to shout: forward, forward. And we took off chasing the police who were running back the way they’d come. One was hit and we went after him, still hitting him. Then we chased the police back to the end of the cross street they’d come out of.

Meanwhile they keep firing teargas everywhere, the air more and more unbreathable, and we have to retreat. The police gradually retake Corso Traiano, but barricades are continually thrown up one behind the other. People who are caught get the shit beaten out of them and get thrown into the prison vans. Lots of police get beaten up. At the same time police reinforcements arrive. They come from Alessandria, from Asti, from Genova. The battalion from Padova that came in the morning wasn’t enough. But the clashes keep spreading. The fighting becomes fiercer outside the Fiat office building, in Corso Traiano, in Corso Agnelli, in all the side streets. In Piazza Bengasi, where the police charge like animals, absurd, senseless violence. But they are attacked from two sides and only escape being surrounded by the skin of their teeth. Deputy commissioner Voria is almost captured. Comrades listening to police radio say they have requested authorisation to open fire.

The comrades block the attacks with more barricades in the smoke and flames. Small groups attack the police, throwing molotovs then escaping into the park in the darkness. Still the low drumming sounds on the pylons. Car bodies in flames. The streets all stripped of paving stones and a huge number of rocks scattered all over the place. The police’s behaviour gets worse and worse, they’re like animals. Teargas is fired at people and directly into apartment buildings to stop people coming out and showing themselves. Deputy commissioner Voria is seen brandishing a grenade launcher and warning people to get out of the windows. Then with more reinforcements arriving the police start to take control of the zone. Later they enter apartment buildings, going right into people’s apartments, where people live, to arrest people, making hundreds of arrests. Even an old woman who gives the police a bit of lip is arrested.

In Piazza Bengasi the attacks and rock barrages continue. The police reinforcements have arrived, and they no longer have to restrict themselves to controlling Mirafiori like before, every now and again making charges to relieve the pressure. Now they’re able to control the whole area. They surround Piazza Bengasi, go into the entranceways of the apartment buildings, rounding people up even in their apartments. At midnight there are still clashes going on. All around Corso Traiano you hear them shouting at the police who drag people out of their apartments: Bastards, pigs, Nazis. They shout from the windows: This is like the Nazi round-ups, you bastards.

So then we decide to go to Nichelino where the battle has been going on all afternoon. It wasn’t easy to get to Nichelino, in the sense that you couldn’t get there by the usual way, which was blocked by a barricade of burnt-out cars. The bridge into the neighbourhood was blocked too. We come by another minor street that leads right into the neighbourhood. All those immigrants, the thousands of proletarians who lived at Nichelino, had built barricades all over the place with cement pipes. They’d pulled down the traffic lights and thrown them into the street. Loads of stuff from building sites was piled in the middle of the street to make barricades, which were then set alight.

Via Sestriere, which crosses Nichelino, is blocked by a dozen barricades of burning cars and trailers, road signs, rocks, timber. In the night huge bonfires of tyres and wood are burning. An enormous fire burns with timber from an apartment block under construction. The whole building site is in flames. The street lights have been smashed with stones and in the dark all you see are flames. The police tried to stall, they left us alone, they held off. They attacked around four in the morning, when reinforcements came. Almost all the workers were exhausted, they’d been fighting for more than twelve hours, while they, the police, had reinforcements.

They’d been waiting there at the barricades, waiting for morning, when fresh troops would arrive to relieve them. We had turned back to defend the bridge blocked by burning cars with rocks, where the reinforcements wanted to pass. But there weren’t many of us left defending the bridge, only twenty or so. Then the jeeps and the trucks with reinforcements came through the side street where we had come in, and to avoid being surrounded we all had to run. Some Carabinieri got out of a truck and came after us firing teargas.

We all fled, chased by the Carabinieri. At one point we saw a line of jeeps coming towards us, right in front. I don’t know how they ended up there, maybe they were coming back from a patrol. Things were turning bad for us. So we all ran at the police, yelling and throwing stones at the jeeps to chase them off. Then we saw that the Carabinieri were behind us, and so we turned around and attacked them. But loads of police were coming up behind the Carabinieri. So we had to run because there were only a few of us left.

By now I was exhausted and I ran like crazy. I got to a field, stumbled on a rock and nearly lost my shoe. When I stopped to look for my shoe a Carabiniere appeared who’d been chasing me on his own. Then I saw a comrade who was running with me jump the Carabiniere. They fought hand to hand and the Carabiniere went down. At one point I saw smoke at the top of a street. We got to the top of the street and from there you could see a wide avenue where the fighting continued. You couldn’t tell who was winning. Everything was so confused. I just wanted to stop somewhere for a shit, I couldn’t hold on any more.

Some Carabinieri attacked us and I couldn’t get into the middle where the fighting was hardest. Right then we heard someone shouting: They’re coming, they’re coming. I saw a huge cloud of smoke rising in the middle of the road and everyone ran back and forth yelling. Then out of the smoke the police appeared in armoured vans with spotlights illuminating everything. They looked big and strong and they were all firing teargas. There was a building site beside the road and a group of us were gathering there. The comrade who was with me headed for the building site and I followed him.

A whole lot of people were running off together down the street. I looked back and saw them all running and scattering into the side streets. When we got to the building site there were already quite a few others there. The police were firing teargas over our heads and knocking down pieces of wood and bricks. We couldn’t see what was going on in the street any more. It was all smoke and shouts and blasts. The street was obscured by smoke and dust and there were only shadows and a din of shouting and sirens and explosions. To my left I heard the roar of motors and the sirens of the police vans that were going back up the street. Two molotovs burst in the middle of the street.

There was smoke and teargas everywhere, you couldn’t breathe. Then the police got out of the vans and ran towards us. They ran through the smoke with masks and shields. I found myself among a lot of our guys who were running back and forth and scattering into the side streets. The police ran after us and we were all there mixed up in the gloom lit by fires and a huge racket. I couldn’t see much, but once I saw one of our guys lay into a policeman who’d been left behind and hit him again and again with a stick.

I saw some police come running out of a side street on our left. We all raised our sticks and threw ourselves at them in the half-light surrounding us. I ran into a policeman with a helmet and hit him. He cried out and fell headlong to the ground. Then we all went back towards the road. On the other side of the road we saw a group of our guys hurling themselves at police who were going back towards the vans. The police fled and we all went after them, chasing them back to the end of the street where the vans were waiting with engines running and spotlights illuminating the road. There was a policeman with his arms raised, groaning. I saw a few of our guys helping a kid get up. I saw that he was injured and bleeding from his head.

With the help of more reinforcements the police slowly took back ground. They started rounding up people house by house, pitiless, brutal. But people didn’t run. Workers and locals relieved each other, they were all used to the teargas by now and they kept on building barricades. Four or five of us being chased by about twenty Carabinieri get to the door of an apartment building and we close it behind us. I climb over a little bit of wall in the courtyard and find myself in a workshop. In the workshop there was a ladder. I climb it and finish up on the roof of this workshop. I pull the ladder up. I see other comrades on the roof of a building next to the one we’d gone into.

Meanwhile the Carabinieri had managed to break down the street door and were going into all the apartments. From my roof I saw them come out onto the balconies, I saw them in the stairways climbing with their helmets and guns, and after a while I saw them come out onto the balconies of the other apartments looking for us. They were waking people in their beds and checking. We stayed there for a bit, we couldn’t tell whether the Carabinieri had gone away or not. Then some women from the apartment who’d seen us gave us the sign that they’d gone, they called us to come down. It was almost dawn, the sun was coming up. We were exhausted, worn out. That was enough now. We climbed down and went back home.

Translated by Matt Holden

VERSO 2016

Comments

Jamie MacKay considers Balestrini's autonomist poetry.

Today’s ongoing debate about the relationship between art and activism is one that too often seems to arrive at a dead end. These two grand abstractions – too grand, too abstract perhaps? – seem to repel one another with an almost magnetic indignation. The possibility of fusion is frustrated by difficult questions, the reductiveness of political language, the vulgarity of propaganda, the sheer ugliness of naked ideology.

Few can claim to have confronted and surpassed this dilemma more effectively than the writer and artist Nanni Balestrini whose poetic craft has, for decades, been intimately embedded in the realities of Italian social movements. His art was born from a particular set of struggles that emerged in the 1960s and 70s, most notably the wave of protests and occupations that would lead to the formation of Autonomia Operaia, a leftist movement which challenged the Communist glorification of work. This disparate group, too often reduced to its concluding apocalyptic violence, has been largely abandoned as a strategic political model. But it is in the artistic sphere, and in Balestrini’s poetic work in particular, that the imaginative legacy of this generation lives on in its most vivid and urgent manifestation.

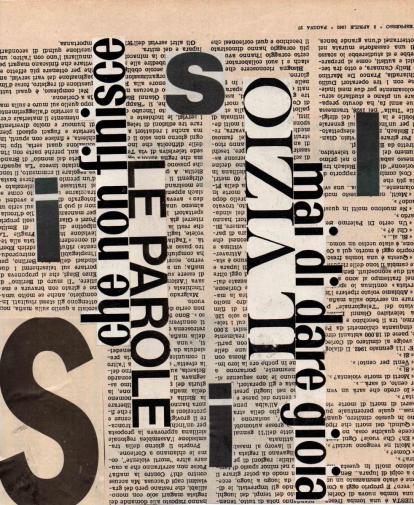

One of the most important examples of this, and the most interesting for both artists and activists today, is Blackout, first published in 1979 and, as of this week, now finally available in English translation thanks to Commune Editions. The text is a perfect example of how literature can expand outside of its usual social boundaries: the private space, the isolated ‘intellect.’ The poem – split in four ‘chapters’ – tells the story of the movement’s birth to its final moments, the dark days in which the ‘lights’ went out. It is a pastiche of the epic, a meditation on the collapse of movements, the loss of hope, community and love.

Blackout is structured through a series of repetitive leitmotifs, composed by the poetic organization of cut up fragments from books, magazines, other poems, transcriptions of radio broadcasts, protest slogans, government reports, even tourist guidebooks. These are then (re)assembled in an ‘intertextual’ collage. This extract from the second verse of the first section is typical of the style:

for days a poster illuminated the walls of Milan

dark clouds swollen with rain transitory showers that lasted the evening then two rainbows

a river of blue jeans

in heaven at last a glimmer of light there will be no flood

a segment of Milan is deadlocked

Each phrase asks the reader to speculate as to its origins, each contains its own individual energy or aura. ‘A segment of Milan is deadlocked’, for example, reeks of journalistic detachment, made all the more obvious by its strange amputation here. Meanwhile, the poster which ‘illuminated’ the walls of Milan has a romanticism, youthful and futuristic. Then there is the ‘glimmer of light,’ in heaven, opposed, of course, to the blackout of the poem’s title. ‘Could this be from the Gospels?’ asks the reader.

At the same time the fragments also have a collective identity by virtue of their position in the verse. Sticking with these first two examples, the difference in tense – past to present – serves to reinforce the distance between the newspaper cutting and presumed activist pamphlet. So too does the physical space between them (not to mention the conflicting rhythms). From this example alone we can see that each poem, collectively, has its own identity, established by the act of remixing. Later, several fragments return in new contexts, entering into new textual relationships:

a river of blue jeans

a carpet that smothers the bleachers and descends to completely hide the lawn

thousands hundreds of thousands of voices for communicating

a carpet of shoulders of heads and arms that seem like agitated waves under gusts of wind

for days a poster illuminated the walls of Milan