A slightly polished version of a short talk for a panel discussion on post-Fordism and mental health with Hannah Black and Mark Fisher, as part of Auto Italia South East's Immaterial Labour Isn't Working 2013 event series.

From the 1970s onwards Marxist feminists paid close attention to the role of affective labour and caring work1 , and expanded our understanding of what counts as “work” into the home, complicating the distinction between public and private, work and leisure time, and asking the question, when are we ever not at work? Arlie Hochschild's The Managed Heart was particularly important in this context in examining forms of labour that demanded not just presence, knowledge, and skill, but demanded too that we put our personalities, values, and affect to work.

When employers demand the mobilisation of our own personalities as a vital part of the labour process, how can we sabotage our work without sabotaging ourselves? This dilemma may have particular resonance in the creative industries where the worker may struggle to reconcile the demands of paid work with their own sense of artistic integrity, but the same dilemma is faced by care workers who draw from their own personal (and sometimes political) values to inform and motivate their work.

Of course, immaterial labour in the creative industries warrants it's own urgent examination and analysis, as here we can clearly see the constant pressure to be “at work”, drawing inspiration from everywhere, constantly investing in and promoting one's own brand, shifting unpredictably between periods of working around the clock to not working at all. And although the work itself is different, we can see similarities between these working conditions and those in other industries – in the social care sector we see a rise of temporary contracts, the outsourcing of work to agencies with relief staff booked at a few hours notice for a shift (a shift you never want to turn down in case you're not offered another), and an emerging two-tier workforce between permanent and temporary staff, in the same workplace doing the same job with different pay and conditions2 .

Immaterial labour at Edinburgh's Fruitmarket Gallery - Abigail Rebakah Barr

Clearly, the challenges faced by the immaterial creative labourer and the affective social care labourer are not identical, and it is not my intention to flatten the particular struggles faced by workers in different industries or to homogenise all forms of labour, but what I hope to emphasise is some of the common challenges we face as part of a wider working class which is being attacked by capital. We also need to be aware of gendered and racial dynamics in the division of labour as a whole to avoid privileging immaterial labour over material labour, or reproducing the hierarchy of white collars over pink and blue. To be blunt, the grim conditions of immaterial labour being examined at present are not new, and Marxist feminists have much to offer their analysis.

Now we've expanded our understanding of work to include reproductive labour, and our working hours stretch further and further into what might have been considered leisure time, why not consider too those workers with no “work”? The constant demands of flexibility, “enterprise”, and availability at no notice for slim chance of reward is after all felt most acutely by the unemployed, now re-branded with subtle ideological semantics as “job seekers”. The demands placed on those claiming Jobseeker's Allowance now include an expectation of 40 hours of “jobseeking” per week monitored through the highly problematic and leaky Universal Jobmatch, useless and demoralising job club sessions, instructions to traipse around town all week giving your CV out in search of hidden vacancies3 – sell yourself! Make your own job! Here we see labour totally dematerialised – there is no actual work, but you've got to keep up the act of searching.

An affectively drenched regime of anxiety, paranoia, and suspicion

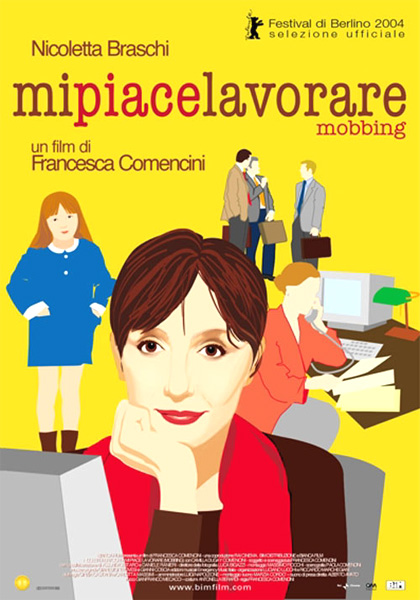

A lack of work, a lack of security, and the speed at which work and it's pursuit comes to occupy our lives and identities takes its toll on our minds and bodies. The demands placed on workers by creeping precariousness manifests in what anthropologist Noelle Molé describes as “an affectively drenched regime of anxiety, paranoia and suspicion”, in which workers can turn against each other. Her work focusses on the practice of “mobbing” in the Italian workplace. A phenomenon highly visible in the Italian workplace from the 1990s onwards, mobbing is the harassment of employees by either managers, co-workers, or both, resulting in the eventual dismissal or resignation of the workers. Mobbing is now legally recognised as a work-related illness, complete with clinics and lawyers, and a growing academic literature devoted to the topic4 .

Mobbing (I Like To Work)

Molé links mobbing to the rise of precarious work practices, against the memory of a protectionist economy with well established and hard won worker's rights. She discusses the psychological torment of workers facing unliveable working conditions combined with an ever present threat of unemployment, and characterises the precarious worker as full of dread for neoliberal horrors still to come, and identifying fully with their insecure and risky positions: I am a precariat, I am temporary. Traditional workerists have used this total identification with employment status as the basis for campaigning, with workers holding signs in photos displaying the dates their contracts run out with the words “I expire on...”.

As workers we're well aware of how the language of precarious and immaterial labour works against us. We know that management speak is bullshit, that “flexibility” means being disposable, a creative approach means doing more with less, a dynamic workplace is a transient one. During my induction at a market research call centre last year, our group leader asked us why telephone interviewers were like the wheels on the company's car5 . When one of our group answered, “because we get worn out really quickly and we're easily replaced?”, it took our trainer a few moments to regain composure and tell us it was actually because we're the ones who keep the company in contact with the ground and keep the machine pushing forward. It was pretty awkward.

We know that work makes us sick, that work follows us home, demanding more and more of our emotions and our personalities. So how do we resist this? The HR department's championing of a work/life balance is not enough, when not only is our leisure time consumed with the task of recovering from work and preparing for work, but our leisure time is itself co-opted by employers looking for “well-rounded” employees, who use their free time productively, investing in their skills, experiences and interests to contribute to their value as workers, to make us better employees6 .

Abigail Rebekah Barr

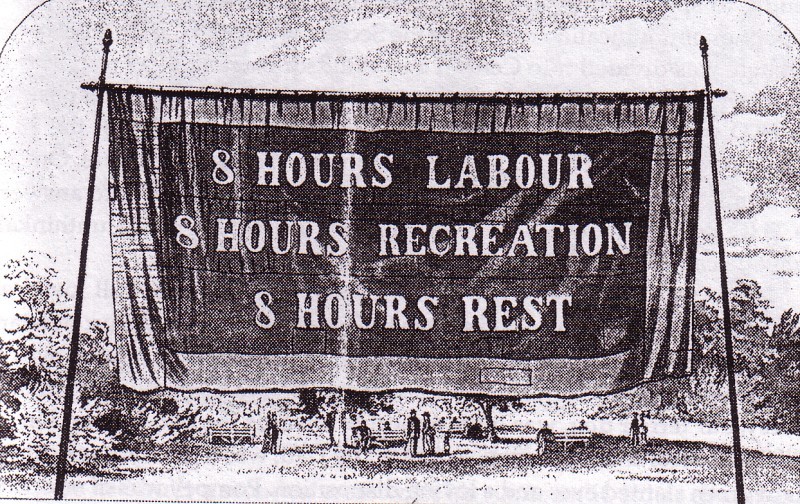

Next week we will commemorate the struggle of the Haymarket martyrs7 , who fought with their lives for the 8 hour working day, with 8 hours for sleep, and 8 hours for “what we will”. We now see this hard won victory slipping away from us, and besides, why did we settle for 8 hours, isn't this still too much? We should be pushing harder, forcing back the imposition of the working week, rejecting the workerist identification of our selves with our jobs, and rejecting those “leftists” who demand a right to work, jobs for all, a party of work. Eight hours to do what we will is not enough8 .

"The division of leisure time is an insult", "A radical transformation of the Fruitmarket Gallery", and "Boycott work/pass out" all used with permission from Abigail Rebekah Barr

- 1by which I mean traditionally “pink collar” occupations such as nursing, social care and so on

- 2this is just a gloss of what could really be it's own piece, but you get the idea

- 3obviously the various government workfare schemes in operation also deserve mention but it's too big a topic for this

- 4an interesting point was raised by libcom admin Steven. in the discussion at this event, that while total working days lost to strike action have decreased, days lost to sickness absence have increased. The individualisation of workplace discontent and the medicalisation of the refusal of work is something I find fascinating and kind of terrifying.

- 5yeah, seriously

- 6it's fairly common for social care interviews to include a question about what you do in your “free” time to de-stress from work, for example, and retail work requires you to demonstrate an all-consuming passion for whatever it is you're selling.

- 7original talk was just before Mayday

- 8hardly a conclusion I know, but it was meant to be a conversation starter not an essay

Comments

I haven't read anything on

I haven't read anything on libcom in a long long long time and this was brilliant. Thank you :)

Thank you! That's really nice

Thank you! That's really nice to hear :)

A recording of this talk and

A recording of this talk and others at the Immaterial Labour Isn't Working event is available here http://iliw13.autoitaliasoutheast.org/recordings/