An extract from Kenan Malik's From Fatwa to Jihad that delves into the roots of the Asian Youth Movements of the 1970s and 1980s and how they came to be formed.

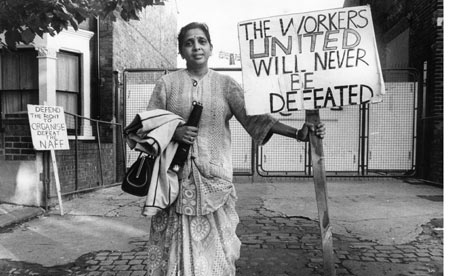

BBC Radio 4 broadcast a documentary this week by Zaiba Malik on the history of the Asian Youth Movements. For many of us who grew up in 1970s and 1980s, the AYMs were a central feature of our lives. Radical and secular, the movements challenged both the vicious racism that defined Britain in that era and many traditional values too, helping to establish an alternative leadership in Asian communities that confronted the conservatives on issues such as the role of women and the dominance of the mosque.Today, in an age in which communities are defined in terms almost solely of faith and culture, when identity politics has ripped apart any sense of radical unity, and when the idea of a ‘secular Muslim’ seems to most people an oxymoron, a movement and a tradition that thirty years ago was highly influential is barely remembered. Zaiba Malik’s documentary was enjoyable, good on the struggle against racism, less sure about the struggle within the communities.

I have written of the AYMs in my book From Fatwa to Jihad. Here is an extract that delves into the roots of the AYMs and how they came to be formed. I will publish a second extract later this week which will look at how the British state and religious conservatives within Asian communities joined forces to marginalise secular radicals. For more details about the AYM, the Tandana archive set up by Anandi Ramamurthy is a good place to start.

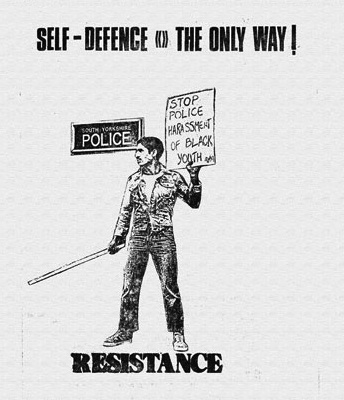

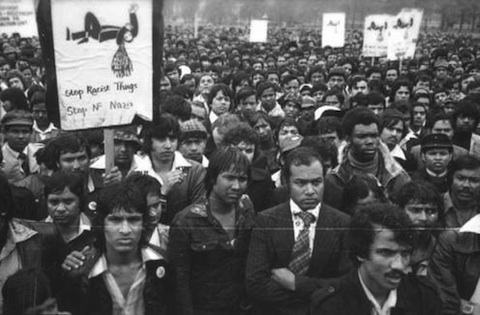

On 17 April 1976 the far-right National Front organised a march through the centre of Manningham, the main Asian area in Bradford. It was to end with a rally at a local school. The National Front was in the late 1970s a minor force in British politics, but more than a bit unpleasant. In 1974 it took 44 per cent of the vote in a parliamentary by-election in Deptford in South London; three years later more than 120,000 voters supported it in London-wide elections. It was on the streets, however, rather that at the ballot box, that the NF preferred to strut its stuff. It had a cadre of thugs often involved in racial assaults and was fond of organising provocative marches through predominantly black and Asian areas. And it was on the streets that a new generation of blacks and Asians decided to take on the NF. This brought them into conflict not just with the fascists but often with their own community leaders, too.

In response to the NF march in Mannigham, local politicians and activists organised a counter-rally in the centre of Bradford. Frustrated by the fact that while racist brutes were marching past their homes in Mannigham, the opposition was rallying several miles away in the safety of the city centre, hundreds of young Asians broke away from the main demonstration, fought their way through police lines and attacked the NF marchers. Bricks were hurled, police vans overturned and 24 people arrested. It was seen by many as the blooding of a new movement. ‘It was there that we really started thinking that we’ve got to get our own house in order’, remembers the novelist Tariq Mehmood, one of those who took part in the breakaway march that day. ‘We can’t have this, we can’t leave our future in the hands of people we hated like community leaders or the Labour Party types.’ That was when, he says, ‘the seeds of the Asian Youth Movements began to be formed.’

About a year after the anti-NF riot, a group of young Asians met in a pub to form the Indian Progressive Youth Association. Why did men and women whose origins lay in Pakistan or Bangladesh call themselves Indian? In large part it was an acknowledgement of their debt to the Indian Workers Association. The IWA had originally been formed in Coventry in 1938 to agitate for Indian independence. It had been wound down after the demise of the Raj, but in the late 1950s it was reformed to give a voice to the new wave of immigrants from the subcontinent. The IWA organized both as a trade union, in factories, on the buses and in hospitals, and as an anti-racist campaigning organization within Asian communities. It had close links to the labour movement in Britain and to the Communist Party of India, and its members invariably supported any action that local trade unions were taking because, as the author and playwright Dilip Hiro put it, ‘they believed that the economic lot of Indian workers was intimately intertwined with that of British workers.’ The IWA was, in fact, often forced to organize industrial action itself, usually to the consternation of mainstream trade unions. In May 1965 it led the first significant postwar ‘immigrant strike’ at Red Scar Mill in Preston, Lancashire, involving Indian, Pakistani and African-Caribbean workers. Over the next decade, the IWA was involved in dozens of industrial disputes, trying to roll back the impact of the first major postwar recession. The economic downturn of the early 70s gutted many of the sectors for which immigrants had been recruited, such as the textile mills. In 1965 there were 50,000 textile workers in Bradford – a third of all those in Britain. Fifteen years later the number had fallen by two-thirds. Asians had always got lower wages and worse conditions than whites. Theirs were the first jobs to go when the cutbacks came. Racism shut the door on any other job prospects. The result was a series of stormy strikes in the mills, led by black and Asian workers.

For black and Asian workers, taking industrial action often meant facing down not just the employer but the casually bigoted attitudes of union officials too. In one famous, and bitter, dispute at Imperial Typewriters in Leicester in 1974, the local union organizer refused to back the mainly Asian women strikers on the grounds that ‘They have got to learn to fit in our ways, you know. We haven’t got to fit into theirs.’ But ‘fitting in’ was exactly what black and Asian workers were doing. Despite the hostility it faced from the local union, the strike committee at Imperial Typewriters insisted that ‘black workers must never for a moment entertain the thought of separate black unions. They must join the existing unions and fight through them.’

Such strikes, and such attitudes, give the lie to the myth that Asian workers did not wish to integrate. They also challenged the belief that Britain became a multicultural nation because minorities demanded that their differences be recognized. For much of the 1960s and 1970s, black and Asian immigrants were concerned less about preserving cultural differences than about fighting for decent wages, proper conditions and equal rights. They recognised that at the heart of the fight for political equality was a commonality of values, hopes and aspirations between blacks and whites, not an articulation of unbridgeable differences. Only later were ideas of cultural and religious separateness to take hold within minority communities.

The IWA was important to Asian communities because it gave voice to the idea of the common interests of immigrant and indigenous workers, and acted upon it. It was, in the 1960s and 1970s, the most influential Asian political organization in Britain. In the West London borough of Southall, the local IWA branch had a membership of 12,500 in the late sixties. Little wonder that the IWA provided an inspiration to a new generation of activists like Tariq Mehmood.

The very name of the Indian Progressive Youth Association showed how insignificant in the 1970s were markers of ‘identity’ that appear so important today. Young Pakistanis and Bangladeshis were so open minded about their origins and identity that they were quite willing to call themselves ‘Indian’, notwithstanding even the bloodshed and turmoil of Partition. But while they were happy to be labelled ‘Indian’, it never entered their heads to call themselves ‘Muslim’. As Mehmood puts it, ‘In the 1970s, I was called a black bastard and a Paki, but not a coloured bastard and very rarely was I called a Muslim’.

Nevertheless, recalls Mehmood, there were problems in calling themselves the Indian Progressive Youth Association because ‘there was this contradiction that we weren’t Indians.’ In any case, for all the inspiration that the IWA provided, many young Asians had come to be critical of its activities. Its leaders were seen as part of the old guard of community spokesmen who had lost touch with the needs and problems of the youth. Indeed, the IWA had helped organize the anti-NF rally in Bradford city centre, the timidity of which young Asians had so despised. So, the following year the organization was renamed the Asian Youth Movement. Defining itself as Asian was not a way of cutting itself off from African Carribeans or whites but an attempt to create a conscious break with the sectarian forms of subcontinental politics that often still corrupted many first generation organizations. In its own way the AYM was to become to a new generation what the IWA had been to an old.

Soon Asian Youth Movements had sprung up all over Britain, in East London, Luton, Nottingham, Leicester, Manchester, Sheffield. Their slogans – ‘Come what may, we are here to stay’ and ‘Here to stay, here to fight’ – revealed a generation determined to be both seen and treated as British citizens. The youth movements challenged many traditional values too, particularly within Muslim communities, helping establish an alternative leadership that confronted traditionalists on issues such as the role of women and the dominance of the mosque. ‘Asian women are the most oppressed section of our community’ observed Liberation, the magazine of the Manchester AYM, perhaps the most progressive of all the AYMs. ‘Although we are living in an industrialised society, most of our people retain feudal values and customs. AYM will struggle against these reactionary aspects of our culture. AYM believes that the emancipation of women is a prerequisite for the liberation of society at large.’

AYM activists were not necessarily atheists. But religion never shaped their politics. The AYMs were secular organisations. ‘I had grown up in a profoundly secular environment’, recalls Balraj Purewal. ‘As a Punjabi I did not think about Muslim or Sikh. At school the person next to me was never a Muslim or Hindu. It never occurred to me to think like that.’ Not only did AYM activists not distinguish themselves as Muslim, Hindu or Sikh, many did not even see themselves as specifically Asian, preferring to call themselves ‘black’. Indeed, the very first ‘Asian’ Youth Movement, which Purewal helped found, did not even call itself Asian. On 4 June 1976, Gurdip Singh Chaggar was stabbed to death by racists outside the Dominion Theatre in Southall, in west London. In the wake of the murder local youth formed themselves into the Southall Youth Movement, the aim of which was both to campaign against discrimination and to provide physical defence for the local area. What was developing here was a peculiarly British notion of blackness and the fermentation of a very British identity. In America, black meant ‘of African origin’. On the Indian subcontinent no one would have defined themselves by their colour. In Britain young blacks and Asians were attempting to forge a more inclusive identity rooted in politics rather than ethnicity or skin colour while at the same time trying to highlight the divisive character of racism.

The Asian Youth Movements drew inspiration from two very different models of political organization. The first was traditional class-based politics in Britain. Activists did not only draw upon the history of organisations such as the IWA. Many had cut their political teeth in far-left Trotskyist groups. Mehmood himself was a member of the International Socialists, the forerunners of the Socialist Workers Party. The other model on which the AYMs drew was the black power movement in America from which came the notion of ‘black self organisation’, the idea that blacks should organize independently of white groups. The clenched fist symbol of the AYM came straight from the Black Panthers.

These two guiding spirits were often in tension. ‘Most of us were workers and sons of workers’, Mehmood recalls. ‘For us race and class were inseparable’. Yet he, like many AYM members, was deeply suspicious of what he called the ‘white left’ and stressed ‘the need for our own organisation’. Indeed, the very ‘formation of the Asian Youth Movement in Bradford’, Anandi Ramamurthy, a historian of the AYM, suggests, ‘was also an expression of the failure of “white” left organizations in Britain to effectively address the issues that affected Asian communities.’ Despite the racist hostility they had faced from white trade unionists, the strikers at Imperial Typewriters rejected the idea of a separate black union. Their children, who formed the backbone of the Asian Youth Movements, rejected the idea that they should work within organizations they saw as racist. ‘We had to put our own house in order’, Mehmood observes, before it was possible to ‘unite as equals’ with the ‘white left’.

Such attitudes were understandable given the sense of isolation that many blacks and Asians felt. But such attitudes could also all too easily lead to what the writer Mala Dhondy has called ‘ghetto politics’. Today Dhondy is better known as Mala Sen, biographer of India’s Bandit Queen, Phoolan Devi. In the 1960s and 70s, she was one of the leaders of Britain’s Black Panther Movement, which modeled itself closely on the American version and provided a political education for a whole generation of black British radicals. The writers Darcus Howe and Farrukh Dondhy (then Sen’s husband) and the dub poet Linton Kwesi Johnson were among her contemporaries in the Panthers.

In the late 1970s Mala Dhondy helped organize Bengalis in East London into the Bengali Housing Action Group (BHAG), a militant squatting movement the aim of which was to end discrimination against Asians in housing allocation. Under pressure from the BHAG the Greater London Council proposed in 1977 that ‘we might continue to meet the wishes of the community by earmarking blocks of flats, or indeed whole estates if necessary, for their community.’ Jean Tathan, the Conservative chair of the GLC Housing Committee, told newspapers that ‘I am prepared to consider applications from all-white or all-West Indian groups’. The plan for colour-coded housing estates caused uproar and was eventually defeated. At that time Mala Dhondy claimed that ‘The GLC has gone beyond what we asked in a potentially dangerous way’. Later, however, she was to defend the idea of ghetto politics. ‘Some people said “You are creating a ghetto”’, Dhondhy argued. ‘We said, “Fine, we prefer the ghetto, at least you have each other to defend yourself”… So that’s what it was and we advanced it, and today you walk around Brick Lane and it’s totally Bengali.’

For Asian communities under siege from racists, there was indeed safety in numbers. It was an age in which racism was vicious, visceral and often fatal, in which stabbings everyday facts of life, firebombings almost weekly events, and murders all too common. An age in which I remember organising street patrols in predominantly-Asain areas to afford protection from racist thugs. An age in which, thanks to discriminatory housing policies, most housing estates, especially good ones, were predominantly white. A 1982 report on housing allocation in East London reported that Bengalis made up just 0.3 of tenants on the best estates and concluded that ‘effectively the GLC has picked out certain old estates’ on which to house Bengalis while keeping newer housing stock ‘almost exclusively white’. In a follow-up report two years later it found little change and suggested that ‘Somewhere, somehow deliberate decisions must have been taken over which estates Bengalis were going to be “allowed” to live on.’

What Mala Dhondy called ‘ghetto politics’ was, however, more than simply a pragmatic response to such racism, more than simply a question of finding protection in numbers. It was also an attitude that came to celebrate the ghetto as an expression not of the segregation of immigrants through poverty or racism but of the cultural distinctiveness of a community. The notion of ‘self-organisation’ originated as a strategy through which to combat racism - ‘We have to get our own house before uniting as equals’. But over time it mutated into a celebration of cultural separation – ‘We are different because we are black and Asian’. The idea of temporary organizational separation for political reasons gave way to the notion of permanent cultural distinctiveness as a fact of life. In the 1980s these ideas moved out of the ghetto of radical anti-racist politics and into mainstream public policy.

[Taken from From Fatwa to Jihad, pp47-54; the extract has been slightly edited. Some of the interviews were conducted specifically for the book, some were taken from other sources; full references are in From Fatwa to Jihad.]

Taken from Kenan Malik's wordpress page on 11th December 2012.

The introduction from From Fatwa to Jihad is reproduced on Kenan Malik's site https://kenanmalik.com/introduction-to-from-fatwa-to-jihad/

Comments

Two essays by Anandi

Two essays by Anandi Ramamurthy:

The politics of Britain's Asian Youth Movements

Secular Identities and the Asian Youth Movements

http://www.irr.org.uk/news/yo

http://www.irr.org.uk/news/young-rebels-with-a-cause/

Brilliant documentary!

Brilliant documentary! Interviews with lots of Southall Youth Movement members.. If you've not watched it then def give it a look:

Young Rebels - The Story of the Southall Youth Movement

http://www.southasiancultural

http://www.southasianculturalstudies.co.uk/Documents/Ali,%20T.%20M.%20-%20SACS%20Vol%204.%20No.%201.pdf

The pool of blood that

The pool of blood that changed my life