A very short overview of Belgian, and latterly US, imperialism in Congo, written by Marty Jezer in 2001.

In recent weeks the Democratic Republic of the Congo, formerly known as Zaire, and before that the Belgian Congo, has been in the news: A brutal civil war, an horrendous AIDS epidemic, the assassination of its dictator, Laurent Kabila, and now a new President, Kabila's son Joseph, who is in Washington for talks with the Bush Administration. These events are usually described in the media without historic context. We in the West shrug in bemusement and wonder why these Africans can't get it together.

Most of us know little about the Congo except, perhaps, if we are old enough, from the little ditty, "Bingo, Bango, Bongo, I don't want to leave the Congo, oh no no no no no." Then there's Joseph Conrad's novel, Heart of Darkness. The main character, Kurtz, is a white trader who surrounds his home in the Congo with shrunken heads. The barbarity that Conrad describes is considered a metaphor for man's capacity for evil, too horrendous to be anything but fiction.

But Conrad, who was witness to the colonization of the Congo, has said that his novel "is experience . . . pushed a little (and only very little) beyond the actual facts of the case."

As individuals and peoples we are products of our past. Events don't unfold in a vacuum. What happens today is an outgrowth of history. To learn the facts of Conrad's case, one can turn to Adam Hochschild's book, King Leopold's Ghost: A Story of Greed, Terror and Heroism in Colonial Africa (Houghton Mifflin, 1998).

Hochschild's book is a history of Belgium's King Leopold's crimes against humanity in the rainforest of equatorial Africa. Leopold felt stifled by his country's parliamentary democracy, as Hochschild tells it. He wanted to rule; if he couldn't rule his own people, he could at least rule over a colony. In 1877 he sent an agent, the American explorer Henry Morton Stanley, into the African rainforest with orders "to purchase as much land as you will be able to obtain" Stanley thereupon negotiated "treaties" with 450 tribal chiefs, documents that were meaningless to the chiefs who agreed to them. Leopold then used the treaties to convince other Western colonial powers that he had legal right to the Congo River basin, an area more than fifty times the size of Belgium. Thus was the Belgian Congo created.

Leopold spoke of bringing civilization to the Africans and sent a small but heavily armed Belgian force into the Congo. This army forcibly conscripted African youth to fill its ranks. It then went from village to village taking the women hostage and forcing the men to go deep into the jungle to tap the indigenous rubber trees. Those who resisted were mowed down by machine-gun fire. Many were beheaded or had their hands cut off. One of the King's officers wrote, "My goal is ultimately humanitarian. I killed a hundred people but that allowed five hundred others to live." Another wrote, "To gather rubber in the district one must cut off hands, noses, and ears."

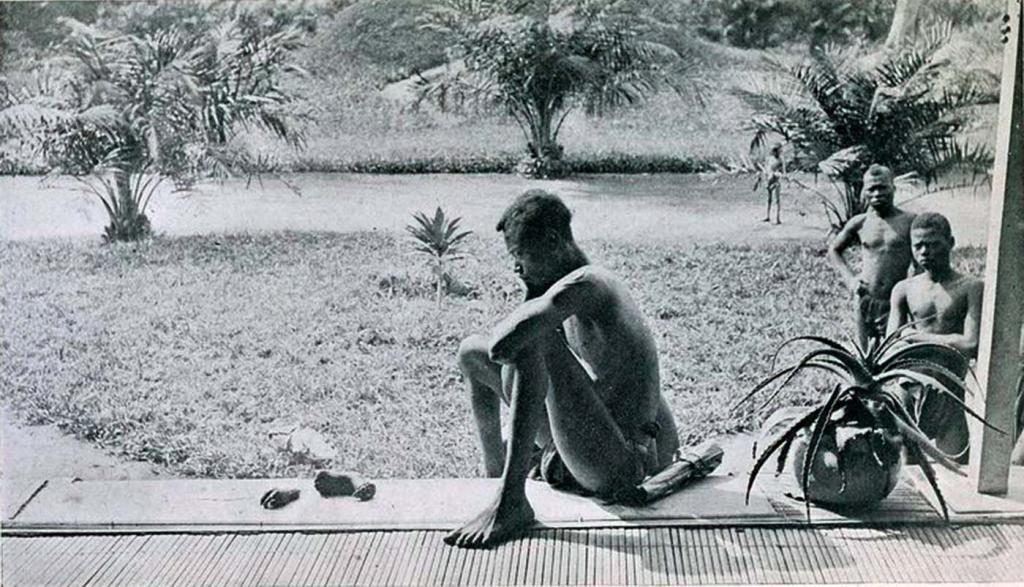

A Congolese worker called Nsala with the severed hand and foot of his five-year-old daughter, Boali. His daughter and wife were killed and eaten by the militia of the Anglo-Belgian India Rubber Company as he hadn't met his rubber quota for the day.1

Those not gunned-down or mutilated were worked as slaves to maximize the rubber harvest. With the men doing forced labor and the women held hostage (and being raped and otherwise brutalized), the native social structure was destroyed. Since there was no one free to hunt game or grow crops, starvation resulted, and with it disease. Between 1880 and 1920, the Congo lost approximately half of its population. An estimated eight to ten million Africans died as victims of King Leopold's "rubber-terror"

International outrage forced Belgium to take over the King's fiefdom, but forced labor continued. Belgium extracted rubber, ivory, diamonds, and uranium from the Congo and gave back nothing: no schools, no hospitals, no infrastructure except that which facilitated the export of resources. The uranium used to make the atom bombs dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki came from mines in the Congo.

In 1960 Belgium gave the Congo independence, but, with other western countries, continued to maintain economic power. One excuse was the Cold War.

In 1961 Patrice Lumumba, the Prime Minister in the Congo's first elected government, was seized, tortured, and murdered by a Colonel named Joseph Mobuto. Lumumba was considered the most brilliant of the Congolese leaders. He also spoke out against Western control of the Congo's resources and was thus considered a "communist."

Belgian historians have uncovered compelling evidence showing that Mobuto was acting under instructions from the CIA and the Belgian government.

In 1965 Mobuto himself seized power and, with the backing of the United States, ruled as an absolute dictator until his overthrow by Kabila. Like King Leopold, Mobuto, who re-named the country Zaire, ran the economy for his own personal profit and, like the Belgians before him, left the Congo impoverished.

Excepted from a slightly longer text here

- 1 libcom note on image added by us: Source: “Don’t Call Me Lady: The Journey of Lady Alice Seeley Harris”

Comments

Not sure if it's worth

Not sure if it's worth uploading but Mark Twain wrote an entire satire on King Leopold II, King Leopold's Soliloquy. Pretty incredible (not really I guess) that Belgium, under the pressure of the 2020 protests, is just now getting around to removing statues of him.