Crimethinc examine the history behind the guillotine, its current popularity as a left symbol, and try to suggest a vision of liberation not based around revenge fantasies.

148 years ago this week, on April 6, 1871, armed participants in the revolutionary Paris Commune seized the guillotine that was stored near the prison in Paris. They brought it to the foot of the statue of Voltaire, where they smashed it into pieces and burned it in a bonfire, to the applause of an immense crowd.1

This was a popular action arising from the grassroots, not a spectacle coordinated by politicians. At the time, the Commune controlled Paris, which was still inhabited by people of all classes; the French and Prussian armies surrounded the city and were preparing to invade it in order to impose the conservative Republican government of Adolphe Thiers. In these conditions, burning the guillotine was a brave gesture repudiating the Reign of Terror and the idea that positive social change can be achieved by slaughtering people.

“What?” you say, in shock, “The Communards burned the guillotine? Why on earth would they do that? I thought the guillotine was a symbol of liberation!”

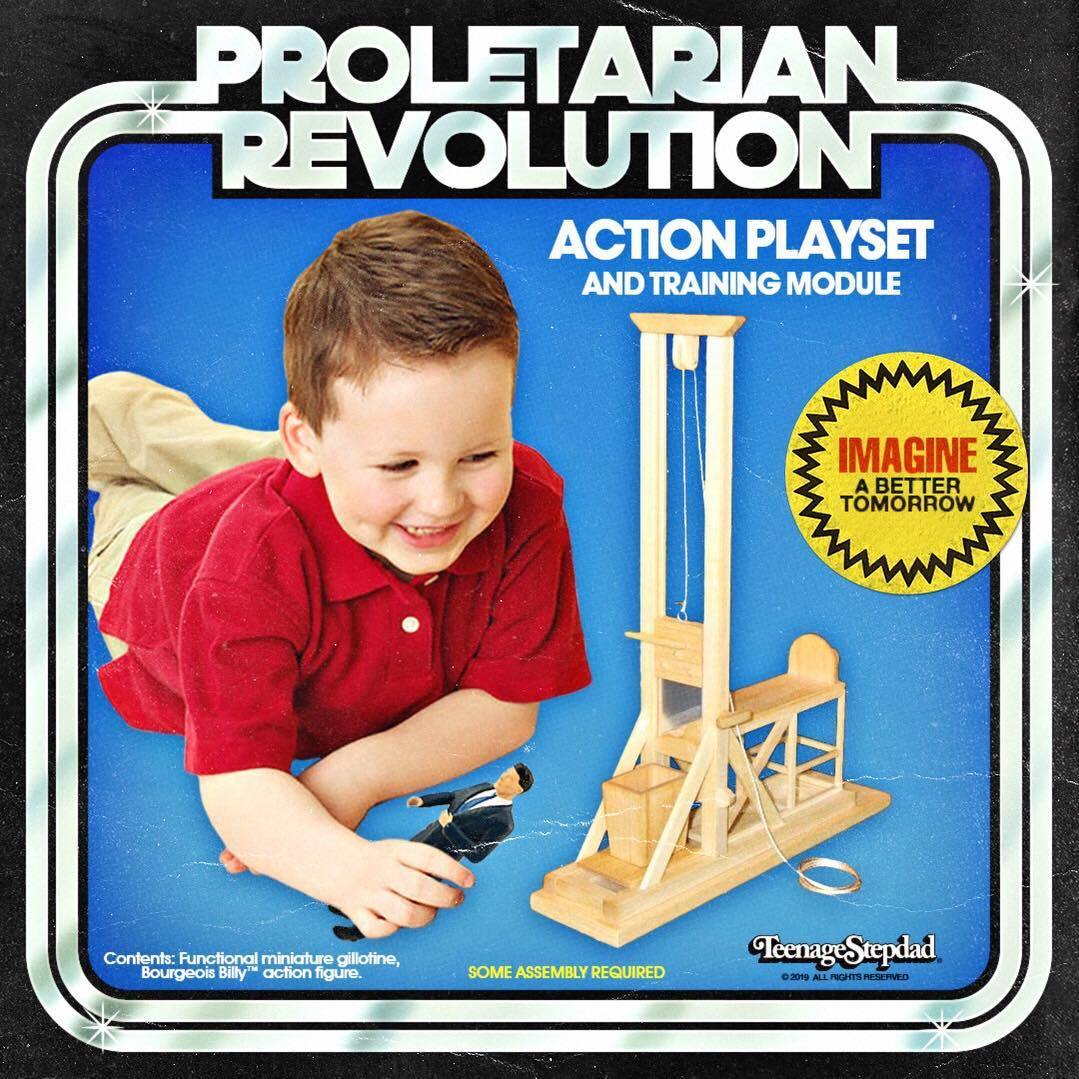

Why indeed? If the guillotine is not a symbol of liberation, then why has it become such a standard motif for the radical left over the past few years? Why is the internet replete with guillotine memes? Why does The Coup sing “We got the guillotine, you better run”? The most popular socialist periodical is named Jacobin, after the original proponents of the guillotine. Surely this can’t all be just an ironic sendup of lingering right-wing anxieties about the original French Revolution.

The guillotine has come to occupy our collective imagination. In a time when the rifts in our society are widening towards civil war, it represents uncompromising bloody revenge.

Those who take their own powerlessness for granted assume that they can promote gruesome revenge fantasies without consequences. But if we are serious about changing the world, we owe it to ourselves to make sure that our proposals are not equally gruesome.

A poster in Seattle, Washington. The quotation is from Karl Marx.

Vengeance

It’s not surprising that people want bloody revenge today. Capitalist profiteering is rapidly rendering the planet uninhabitable. US Border Patrol is kidnapping, drugging, and imprisoning children. Individual acts of racist and misogynist violence occur regularly. For many people, daily life is increasingly humiliating and disempowering.

Those who don’t desire revenge because they are not compassionate enough to be outraged about injustice or because they are simply not paying attention deserve no credit for this. There is less virtue in apathy than in the worst excesses of vengefulness.

Do I want to take revenge on the police officers who murder people with impunity, on the billionaires who cash in on exploitation and gentrification, on the bigots who harass and dox people? Yes, of course I do. They have killed people I knew; they are trying to destroy everything I love. When I think about the harm that they are causing, I feel ready to break their bones, to kill them with my bare hands.

But that desire is distinct from my politics. I can want something without having to reverse-engineer a political justification for it. I can want something and choose not to pursue it, if I want something else even more—in this case, an anarchist revolution that is not based in revenge. I don’t judge other people for wanting revenge, especially if they have been through worse than I have. But I also don’t confuse that desire with a proposal for liberation.

If the sort of bloodlust I describe scares you, or if it simply seems unseemly, then you absolutely have no business joking about other people carrying out industrialized murder on your behalf.

For this is what distinguishes the fantasy of the guillotine: it is all about efficiency and distance. Those who fetishize the guillotine don’t want to kill people with their bare hands; they aren’t prepared to rend anyone’s flesh with their teeth. They want their revenge automated and carried out for them. They are like the consumers who blithely eat Chicken McNuggets but could never personally butcher a cow or cut down a rainforest. They prefer for bloodshed to take place in an orderly manner, with all the paperwork filled out properly, according to the example set by the Jacobins and the Bolsheviks in imitation of the impersonal functioning of the capitalist state.

And one more thing: they don’t want to have to take responsibility for it. They prefer to express their fantasy ironically, retaining plausible deniability. Yet anyone who has ever participated actively in social upheaval knows how narrow the line can be between fantasy and reality. Let’s look at the “revolutionary” role the guillotine has played in the past.

“But revenge is unworthy of an anarchist! The dawn, our dawn, claims no quarrels, no crimes, no lies; it affirms life, love, knowledge; we work to hasten that day.”

- Kurt Gustav Wilckens—anarchist, pacifist, and assassin of Colonel Héctor Varela, the Argentine official who had overseen the slaughter of approximately 1500 striking workers in Patagonia.

A Very Brief History of the Guillotine

The guillotine is associated with radical politics because it was used in the original French Revolution to behead monarch Louis XVI on January 21, 1793, several months after his arrest. But once you open the Pandora’s box of exterminatory force, it’s difficult to close it again.

Having gotten started using the guillotine as an instrument of social change, Maximilien de Robespierre, sometime President of the Jacobin Club, continued employing it to consolidate power for his faction of the Republican government. As is customary for demagogues, Robespierre, Georges Danton, and other radicals availed themselves of the assistance of the sans-culottes, the angry poor, to oust the more moderate faction, the Girondists, in June 1793. (The Girondists, too, were Jacobins; if you love a Jacobin, the best thing you can do for him is to prevent his party from coming to power, since he is certain to be next up against the wall after you.) After guillotining the Girondists en masse, Robespierre set about consolidating power at the expense of Danton, the sans-culottes, and everyone else.

“The revolutionary government has nothing in common with anarchy. On the contrary, its goal is to suppress it in order to ensure and solidify the reign of law.”

-Maximilien Robespierre, distinguishing his autocratic government from the more radical grassroots movements that helped to create the French Revolution.2

By early 1794, Robespierre and his allies had sent a great number of people at least as radical as themselves to the guillotine, including Anaxagoras Chaumette and the so-called Enragés, Jacques Hébert and the so-called Hébertists, proto-feminist and abolitionist Olympe de Gouges, Camille Desmoulins (who had had the gall to suggest to his childhood friend Robespierre that “love is stronger and more lasting than fear”)—and Desmoulins’s wife, for good measure, despite her sister having been Robespierre’s fiancée. They also arranged for the guillotining of Georges Danton and Danton’s supporters, alongside various other former allies. To celebrate all this bloodletting, Robespierre organized the Festival of the Supreme Being, a mandatory public ceremony inaugurating an invented state religion.3

“Here lies all of France,” reads the inscription on the tomb behind Robespierre in this political cartoon referencing all the executions he helped arrange.

After this, it was only a month and a half before Robespierre himself was guillotined, having exterminated too many of those who might have fought beside him against the counterrevolution. This set the stage for a period of reaction that culminated with Napoleon Bonaparte seizing power and crowning himself Emperor. According to the French Republican Calendar (an innovation that did not catch on, but was briefly reintroduced during the Paris Commune), Robespierre’s execution took place during the month of Thermidor. Consequently, the name Thermidor is forever associated with the onset of the counterrevolution.

“Robespierre killed the Revolution in three blows: the execution of Hébert, the execution of Danton, the Cult of the Supreme Being… The victory of Robespierre, far from saving it, would have meant only a more profound and irreparable fall.”

-Louis-Auguste Blanqui, himself hardly an opponent of authoritarian violence.

But it is a mistake to focus on Robespierre. Robespierre himself was not a superhuman tyrant. At best, he was a zealous apparatchik who filled a role that countless revolutionaries were vying for, a role that another person would have played if he had not. The issue was systemic—the competition for centralized dictatorial power—not a matter of individual wrongdoing.

The tragedy of 1793-1795 confirms that whatever tool you use to bring about a revolution will surely be used against you. But the problem is not just the tool, it’s the logic behind it. Rather than demonizing Robespierre—or Lenin, Stalin, or Pol Pot—we have to examine the logic of the guillotine.

To a certain extent, we can understand why Robespierre and his contemporaries ended up relying on mass murder as a political tool. They were threatened by foreign military invasion, internal conspiracies, and counterrevolutionary uprisings; they were making decisions in an extremely high-stress environment. But if it is possible to understand how they came to embrace the guillotine, it is impossible to argue that all the killings were necessary to secure their position. Their own executions refute that argument eloquently enough.

Likewise, it is wrong to imagine that the guillotine was employed chiefly against the ruling class, even at the height of Jacobin rule. Being consummate bureaucrats, the Jacobins kept detailed records. Between June 1793 and the end of July 1794, 16,594 people were officially sentenced to death in France, including 2639 people in Paris. Of the formal death sentences passed under the Terror, only 8 percent were doled out to aristocrats and 6 percent to members of the clergy; the rest were divided between the middle class and the poor, with the vast majority of the victims coming from the lower classes.

The execution of Robespierre and his colleagues. Robespierre is identified by the number 10; sitting in the cart, he holds a handkerchief to his mouth, having been shot in the jaw during his capture.

The story that played out in the first French revolution was not a fluke. Half a century later, the French Revolution of 1848 followed a similar trajectory. In February, a revolution led by angry poor people gave Republican politicians state power; in June, when life under the new government turned out to be little better than life under the king, the people of Paris revolted once again and the politicians ordered the army to massacre them in the name of the revolution. This set the stage for the nephew of the original Napoleon to win the presidential election of December 1848, promising to “restore order.” Three years later, having exiled all the Republican politicians, Napoleon III abolished the Republic and crowned himself Emperor—prompting Marx’s famous quip that history repeats itself, “the first time as tragedy, the second time as farce.”

Likewise, after the French revolution of 1870 put Adolphe Thiers in power, he ruthlessly butchered the Paris Commune, but this only paved the way for even more reactionary politicians to supplant him in 1873. In all three of these cases, we see how revolutionaries who are intent on wielding state power must embrace the logic of the guillotine to acquire it, and then, having brutally crushed other revolutionaries in hopes of consolidating control, are inevitably defeated by more reactionary forces.

In the 20th century, Lenin described Robespierre as a Bolshevik avant la lettre, affirming the Terror as an antecedent of the Bolshevik project. He was not the only person to draw that comparison.

“We’ll be our own Thermidor,” Bolshevik apologist Victor Serge recalls Lenin proclaiming as he prepared to butcher the rebels of Kronstadt. In other words, having crushed the anarchists and everyone else to the left of them, the Bolsheviks would survive the reaction by becoming the counterrevolution themselves. They had already reintroduced fixed hierarchies into the Red Army in order to recruit former Tsarist officers to join it; alongside their victory over the insurgents in Kronstadt, they reintroduced the free market and capitalism, albeit under state control. Eventually Stalin assumed the position once occupied by Napoleon.

So the guillotine is not an instrument of liberation. This was already clear in 1795, well over a century before the Bolsheviks initiated their own Terror, nearly two centuries before the Khmer Rouge exterminated almost a quarter of the population of Cambodia.

Why, then, has the guillotine come back into fashion as a symbol of resistance to tyranny? The answer to this will tell us something the psychology of our time.

Fetishizing the Violence of the State

It is shocking that even today, radicals would associate themselves with the Jacobins, a tendency that was reactionary by the end of 1793. But the explanation isn’t hard to work out. Then, as now, there are people who want to think of themselves as radical without having to actually make a radical break with the institutions and practices that are familiar to them. “The tradition of all dead generations weighs like a nightmare on the brains of the living,” as Marx said.

If—to use Max Weber’s famous definition—an aspiring government qualifies as representing the state by achieving a monopoly on the legitimate use of physical force within a given territory, then one of the most persuasive ways it can demonstrate its sovereignty is to wield lethal force with impunity. This explains the various reports to the effect that public beheadings were observed as festive or even religious occasions during the French Revolution. Before the Revolution, beheadings were affirmations of the sacred authority of the monarch; during the Revolution, when the representatives of the Republic presided over executions, this confirmed that they held sovereignty—in the name of The People, of course. “Louis must die so that the nation may live,” Robespierre had proclaimed, seeking to sanctify the birth of bourgeois nationalism by literally baptizing it in the blood of the previous social order. Once the Republic was inaugurated on these grounds, it required continuous sacrifices to affirm its authority.

Here we see the essence of the state: it can kill, but it cannot give life. As the concentration of political legitimacy and coercive force, it can do harm, but it cannot establish the kind of positive freedom that individuals experience when they are grounded in mutually supportive communities. It cannot create the kind of solidarity that gives rise to harmony between people. What we use the state to do to others, others can use the state to do to us—as Robespierre experienced—but no one can use the coercive apparatus of the state for the cause of liberation.

For radicals, fetishizing the guillotine is just like fetishizing the state: it means celebrating an instrument of murder that will always be used chiefly against us.

Those who have been stripped of a positive relationship to their own agency often look around for a surrogate to identify with—a leader whose violence can stand in for the revenge they desire as a consequence of their own powerlessness. In the Trump era, we are all well aware of what this looks like among disenfranchised proponents of far-right politics. But there are also people who feel powerless and angry on the left, people who desire revenge, people who want to see the state that has crushed them turned against their enemies.

Reminding “tankies” of the atrocities and betrayals state socialists perpetrated from 1917 on is like calling Trump racist and sexist. Publicizing the fact that Trump is a serial sexual assaulter only made him more popular with his misogynistic base; likewise, the blood-drenched history of authoritarian party socialism can only make it more appealing to those who are chiefly motivated by the desire to identify with something powerful.

Now that the Soviet Union has been defunct for almost 30 years—and owing to the difficulty of receiving firsthand perspectives from the exploited Chinese working class—many people in North America experience authoritarian socialism as an entirely abstract concept, as distant from their lived experience as mass executions by guillotine. Desiring not only revenge but also a deus ex machina to rescue them from both the nightmare of capitalism and the responsibility to create an alternative to it themselves, they imagine the authoritarian state as a champion that could fight on their behalf. Recall what George Orwell said of the comfortable British Stalinist writers of the 1930s in his essay “Inside the Whale”:

“To people of that kind such things as purges, secret police, summary executions, imprisonment without trial etc., etc., are too remote to be terrifying. They can swallow totalitarianism because they have no experience of anything except liberalism.”

Punishing the Guilty

“Trust visions that don’t feature buckets of blood.”

-Jenny Holzer

By and large, we tend to be more aware of the wrongs committed against us than we are of the wrongs we commit against others. We are most dangerous when we feel most wronged, because we feel most entitled to pass judgment, to be cruel. The more justified we feel, the more careful we ought to be not to replicate the patterns of the justice industry, the assumptions of the carceral state, the logic of the guillotine. Again, this does not justify inaction; it is simply to say that we must proceed most critically precisely when we feel most righteous, lest we assume the role of our oppressors.

When we see ourselves as fighting against specific human beings rather than social phenomena, it becomes more difficult to recognize the ways that we ourselves participate in those phenomena. We externalize the problem as something outside ourselves, personifying it as an enemy that can be sacrificed to symbolically cleanse ourselves. Yet what we do to the worst of us will eventually be done to the rest of us.

As a symbol of vengeance, the guillotine tempts us to imagine ourselves standing in judgment, anointed with the blood of the wicked. The Christian economics of righteousness and damnation is essential to this tableau. On the contrary, if we use it to symbolize anything, the guillotine should remind us of the danger of becoming what we hate. The best thing would be to be able to fight without hatred, out of an optimistic belief in the tremendous potential of humanity.

Often, all it takes to be able to cease to hate a person is to succeed in making it impossible for him to pose any kind of threat to you. When someone is already in your power, it is contemptible to kill him. This is the crucial moment for any revolution, the moment when the revolutionaries have the opportunity to take gratuitous revenge, to exterminate rather than simply to defeat. If they do not pass this test, their victory will be more ignominious than any failure.

The worst punishment anyone could inflict on those who govern and police us today would be to compel them to live in a society in which everything they’ve done is regarded as embarrassing—for them to have to sit in assemblies in which no one listens to them, to go on living among us without any special privileges in full awareness of the harm they have done. If we fantasize about anything, let us fantasize about making our movements so strong that we will hardly have to kill anyone to overthrow the state and abolish capitalism. This is more becoming of our dignity as partisans of liberation.

It is possible to be committed to revolutionary struggle by all means necessary without holding life cheap. It is possible to eschew the sanctimonious moralism of pacifism without thereby developing a cynical lust for blood. We need to develop the ability to wield force without ever mistaking power over others for our true objective, which is to collectively create the conditions for the freedom of all.

“That humanity might be redeemed from revenge: that is for me the bridge to the highest hope and a rainbow after lashing storms.”

-Friedrich Nietzsche (not himself a partisan of liberation, but one of the foremost theorists of the hazards of vengefulness)

Communards burning the guillotine as a “servile instrument of monarchist domination” at the foot of the statue of Voltaire in Paris on April 6, 1871.

Instead of the Guillotine

Of course, it’s pointless to appeal to the better nature of our oppressors until we have succeeded in making it impossible for them to benefit from oppressing us. The question is how to accomplish that.

Apologists for the Jacobins will protest that, under the circumstances, at least some bloodletting was necessary to advance the revolutionary cause. Practically all of the revolutionary massacres in history have been justified on the grounds of necessity—that’s how people always justify massacres. Even if some bloodletting were necessary, that it is still no excuse to cultivate bloodlust and entitlement as revolutionary values. If we wish to wield coercive force responsibly when there is no other choice, we should cultivate a distaste for it.

Have mass killings ever helped us advance our cause? Certainly, the comparatively few executions that anarchists have carried out—such as the killings of pro-fascist clergy during the Spanish Civil War—have enabled our enemies to depict us in the worst light, even if they are responsible for ten thousand times as many murders. Reactionaries throughout history have always disingenuously held revolutionaries to a double standard, forgiving the state for murdering civilians by the million while taking insurgents to task for so much as breaking a window. The question is not whether they have made us popular, but whether they have a place in a project of liberation. If we seek transformation rather than conquest, we ought to appraise our victories according to a different logic than the police and militaries we confront.

This is not an argument against the use of force. Rather, it is a question about how to employ it without creating new hierarchies, new forms of systematic oppression.

A taxonomy of revolutionary violence.

The image of the guillotine is propaganda for the kind of authoritarian organization that can avail itself of that particular tool. Every tool implies the forms of social organization that are necessary to employ it. In his memoir, Bash the Rich, Class War veteran Ian Bone quotes Angry Brigade member John Barker to the effect that “petrol bombs are far more democratic than dynamite,” suggesting that we should analyze every tool of resistance in terms of how it structures power. Critiquing the armed struggle model adopted by hierarchical authoritarian groups in Italy in the 1970s, Alfredo Bonanno and other insurrectionists emphasized that liberation could only be achieved via horizontal, decentralized, and participatory methods of resistance.

“It is impossible to make the revolution with the guillotine alone. Revenge is the antechamber of power. Anyone who wants to avenge themselves requires a leader. A leader to take them to victory and restore wounded justice.”

-Alfredo Bonanno, Armed Joy

Together, a rioting crowd can defend an autonomous zone or exert pressure on authorities without need of hierarchical centralized leadership. Where this becomes impossible—when society has broken up into two distinct sides that are fully prepared to slaughter each other via military means—one may no longer speak of revolution, but only of war. The premise of revolution is that subversion can spread across the lines of enmity, destabilizing fixed positions, undermining the allegiances and assumptions that underpin authority. We should never hurry to make the transition from revolutionary ferment to warfare. Doing so usually forecloses possibilities rather than expanding them.

As a tool, the guillotine takes for granted that it is impossible to transform one’s relations with the enemy, only to abolish them. What’s more, the guillotine assumes that the victim is already completely within the power of the people who employ it. By contrast with the feats of collective courage we have seen people achieve against tremendous odds in popular uprisings, the guillotine is a weapon for cowards.

By refusing to slaughter our enemies wholesale, we hold open the possibility that they might one day join us in our project of transforming the world. Self-defense is necessary, but wherever we can, we should take the risk of leaving our adversaries alive. Not doing so guarantees that we will be no better than the worst of them. From a military perspective, this is a handicap; but if we truly aspire to revolution, it is the only way.

Liberate, not Exterminate

“To give hope to the many oppressed and fear to the few oppressors, that is our business; if we do the first and give hope to the many, the few must be frightened by their hope. Otherwise, we do not want to frighten them; it is not revenge we want for poor people, but happiness; indeed, what revenge can be taken for all the thousands of years of the sufferings of the poor?”

-William Morris, “How We Live and How We Might Live”

So we repudiate the logic of the guillotine. We don’t want to exterminate our enemies. We don’t think the way to create harmony is to subtract everyone who does not share our ideology from the world. Our vision is a world in which many worlds fit, as Subcomandante Marcos put it—a world in which the only thing that is impossible is to dominate and oppress.

Anarchism is a proposal for everyone regarding how we might go about improving our lives—workers and unemployed people, people of all ethnicities and genders and nationalities or lack thereof, paupers and billionaires alike. The anarchist proposal is not in the interests of one currently existing group against another: it is not a way to enrich the poor at the expense of the rich, or to empower one ethnicity, nationality, or religion at others’ expense. That entire way of thinking is part of what we are trying to escape. All of the “interests” that supposedly characterize different categories of people are products of the prevailing order and must be transformed along with it, not preserved or pandered to.

From our perspective, even the topmost positions of wealth and power that are available in the existing order are worthless. Nothing that capitalism and the state have to offer are of any value to us. We propose anarchist revolution on the grounds that it could finally fulfill longings that the prevailing social order will never satisfy: the desire to be able to provide for oneself and one’s loved ones without doing so at anyone else’s expense, the wish to be valued for one’s creativity and character rather than for how much profit one can generate, the longing to structure one’s life around what is profoundly joyous rather than according to the imperatives of competition.

We propose that everyone now living could get along—if not well, then at least better—if we were not forced to compete for power and resources in the zero-sum games of politics and economics.

Leave it to anti-Semites and other bigots to describe the enemy as a type of people, to personify everything they fear as the Other. Our adversary is not a kind of human being, but the form of social relations that imposes antagonism between people as the fundamental model for politics and economics. Abolishing the ruling class does not mean guillotining everyone who currently owns a yacht or penthouse; it means making it impossible for anyone to systematically wield coercive power over anyone else. As soon as that is impossible, no yacht or penthouse will sit empty long.

As for our immediate adversaries—the specific human beings who are determined to maintain the prevailing order at all costs—we aspire to defeat them, not to exterminate them. However selfish and rapacious they appear, at least some of their values are similar to ours, and most of their errors—like our own—arise from their fears and weaknesses. In many cases, they oppose the proposals of the Left precisely because of what is internally inconsistent in them—for example, the idea of bringing about the fellowship of humanity by means of violent coercion.

Even when we are engaged in pitched physical struggle with our adversaries, we ought to maintain a profound faith in their potential, for we hope to live in different relations with them one day. As aspiring revolutionaries, this hope is our most precious resource, the foundation of everything we do. If revolutionary change is to spread throughout society and across the world, those we fight today will have to be fighting alongside us tomorrow. We do not preach conversion by the sword, nor do we imagine that we will persuade our adversaries in some abstract marketplace of ideas; rather, we aim to interrupt the ways that capitalism and the state currently reproduce themselves while demonstrating the virtues of our alternative inclusively and contagiously. There are no shortcuts when it comes to lasting change.

Precisely because it is sometimes necessary to employ force in our conflicts with the defenders of the prevailing order, it is especially important that we never lose sight of our aspirations, our compassion, and our optimism. When we are compelled to use coercive force, the only possible justification is that it is a necessary step towards creating a better world for everyone—including our enemies, or at least their children. Otherwise, we risk becoming the next Jacobins, the next defilers of the revolution.

“The only real revenge we could possibly have would be by our own efforts to bring ourselves to happiness.”

-William Morris, in response to calls for revenge for police attacks on demonstrations in Trafalgar Square

Voltaire applauding the burning the guillotine during the Paris Commune.

Appendix: The Beheaded

The guillotine did not end its career with the conclusion of the first French Revolution, nor when it was burned during the Paris Commune. In fact, it was used in France as a means for the state to carry out capital punishment right up to 1977. One of the last women guillotined in France was executed for providing abortions. The Nazis guillotined about 16,500 people between 1933 and 1945—the same number of people killed during the peak of the Terror in France.

A few victims of the guillotine:

- Ravachol (born François Claudius Koenigstein), anarchist

- Auguste Vaillant, anarchist

- Emile Henry, anarchist

- Sante Geronimo Caserio, anarchist

- Raymond Caillemin, Étienne Monier and André Soudy, all anarchist participants in the so-called Bonnot Gang

- Mécislas Charrier, anarchist

- Felice Orsini, who attempted to assassinate Napoleon III

- Hans and Sophie Scholl and Christoph Probst—members of Die Weisse Rose, an underground anti-Nazi youth organization active in Munich 1942-1943.

Emile Henry.

Sante Geronimo Caserio.

André Soudy, Edouard Carouy, Octave Garnier, Etienne Monier.

Hans and Sophie Scholl and Christoph Probst.

“I am an anarchist. We have been hanged in Chicago, electrocuted in New York, guillotined in Paris and strangled in Italy, and I will go with my comrades. I am opposed to your Government and to your authority. Down with them. Do your worst. Long live Anarchy.”

Further Reading

The Guillotine At Work, GP Maximoff

- 1As reported in the official journal of the Paris Commune:

“On Thursday, at nine o’clock in the morning, the 137th battalion, belonging to the eleventh arrondissement, went to Rue Folie-Mericourt; they requisitioned and took the guillotine, broke the hideous machine into pieces, and burned it to the applause of an immense crowd.

“They burned it at the foot of the statue of the defender of Sirven and Calas, the apostle of humanity, the precursor of the French Revolution, at the foot of the statue of Voltaire.”

This had been announced earlier in the following proclamation:

“Citizens,

“We have been informed of the construction of a new type of guillotine that was commissioned by the odious government [i.e., the conservative Republican government under Adolphe Thiers]—one that it is easier to transport and speedier. The Sub-Committee of the 11th Arrondissement has ordered the seizure of these servile instruments of monarchist domination and has voted that they be destroyed once and forever. They will therefore be burned at 10 o’clock on April 6, 1871, on the Place de la Mairies, for the purification of the Arrondissement and the consecration of our new freedom.”

- 2As we have argued elsewhere, fetishizing “the rule of law” often serves to legitimize atrocities that would otherwise be perceived as ghastly and unjust. History shows again and again how centralized government can perpetrate violence on a much greater scale than anything that arises in “unorganized chaos.”

- 3Nauseatingly, at least one contributor to Jacobin magazine has even attempted to rehabilitate this precursor to the worst excesses of Stalinism, pretending that a state-mandated religion could be preferable to authoritarian atheism. The alternative to both authoritarian religions and authoritarian ideologies that promote Islamophobia and the like is not for an authoritarian state to impose a religion of its own, but to build grassroots solidarity across political and religious lines in defense of freedom of conscience.

Comments

.

.

Leftist forums and social

Leftist forums and social media are awash with future threats and jokes about the coming massacres, with Guillotines being extremely common. A bit like how explicit right wing types keep talking about helicopter rides.

A lot of these are jokes, anecdotally speaking a lot of them are made by people whose concept of liberation involves quite a lot of pointless revanchist acts.

zugzwang wrote: Curious what

zugzwang

What Reddebrek said, basically - do you do social media at all, or at least engage with the "left" side of it? (If you don't, or manage to use it solely for posting pictures of your pets and looking at other people's, then that's probably a wise choice and I commend you.) It's definitely something that's pretty noticeable to me - leaving aside the illustrations shown in that article, and a certain podcast that's no longer airing, there's a lot of guillotine memes out there. There's also a lot of gulag ones, but I'd hope those are likely to be less popular among people who'd describe themselves as anarchists. Also, that Coup lyric wasn't just a random quote, but one that people were chanting in the street on a recent demo.

Happy to say that I'd give the DKs a pretty clean bill of health here, in that, as far as you can take it as a serious statement of intent, lynching the landlord would still be much closer to the kinds of hands-on, spontaneous, insurrectional violence, rather than something comething from a state system of punishment like a guillotine.

Boots is a nice guy, super

Boots is a nice guy, super talented, and increasingly popular among more mainstream folks. That's enough of a reason to remember/point out his actual politics. He's a red diaper baby, his parents being longtime members of the Progressive Labor Party, a right-wing (socially conservative) Maoist outfit. Boots himself has been publicly involved with PLP since his early teens, and remains part of their various groupings. Maoists are no friends of self-organized revolutionary projects.

These chappies seem to be all

These chappies seem to be all for it...

https://youtu.be/j9F7Ox2cv2A

.

.

The essay doesn't deal with

The essay doesn't deal with the death of Mussolini - which came up recently on twitter when Jim Carrey (yes that one) did an illustration of Mussolini being hung upside down, and Mussolini's grand daughter (yes really, and she's still an active fascist) spent multiple days saying how great Mussolini is.

While there's various conspiracy theories abut Mussolini's death, if we take the basic narrative of 'he got caught by partisans, was summarily shot, then his body was dumped in a village square to be spontaneously abused' it's a lot closer to the 'lynch your landlord' insurrectionary vengeance than either the mass spectacle and organised violence of the guillotine or prison labour.

zugzwang wrote: Not really.

zugzwang

I would really recommend people read modern-day Crimethinc stuff rather than dismissing them on the basis of 2000s-era beef - they have a lot of stuff like indepth reporting from the Yellow Vests movement, detailed historical coverage of crucial moments in the Bolshevik counterrevolution, extensive coverage of the Network case in Russia, Brazilian anarchists responding to the rise of Bolsonaro, and one of the most impressive strategic pieces I've seen in a while considering the possible ways capital could evolve over the next few decades and attempt to solve its various crises. Although there's no accounting for taste, I suppose, I quite like their house writing style most of the time, but if you hate it then I appreciate that could be a bit offputting.

Not wanting to be too argumentative here, but since you've just said you don't pay much attention to social media, I think you might be missing a lot about the ways that people express this stuff online. If you just do a twitter search for "guillotine billionaire" then I think you get an impression of what they mean. I don't think this is a coincidence that this stuff has gone hand-in-hand with a revival of some of the most discredited and brutally authoritarian tendencies on the left.

And if the point is just "a lot of people talk about guillotines, but most of them don't literally want to behead people", then the article deals with precisely that point:

"Those who take their own powerlessness for granted assume that they can promote gruesome revenge fantasies without consequences. But if we are serious about changing the world, we owe it to ourselves to make sure that our proposals are not equally gruesome...

And one more thing: they don’t want to have to take responsibility for it. They prefer to express their fantasy ironically, retaining plausible deniability. Yet anyone who has ever participated actively in social upheaval knows how narrow the line can be between fantasy and reality."

Mike

Yeah, the "Jim Carrey vs Mussolini" thing is one of those things about 2019 that I imagine would be very difficult to explain to, say, someone who's just woken up from a twenty-year coma. But I think it's still kind of besides the point - shooting fascist dictators might be a much more OK fantasy than mass executions, but it's still much less exciting than bringing about social conditions where we don't need to shoot anyone because there's no possibility of anyone becoming a fascist dictator. Or at least it should be, and if we can't find a way of articulating that vision in a way that sounds more exciting and appealing then we're in trouble.

Noah

Huh, hadn't heard that one before, but it's a banger. Did find myself wondering while reading the article whether Death Grips might also bear some responsibility for popularising that imagery.

Wow, that is fucking

Wow, that is fucking brilliant! Gotta hear me some more of that!

.

.

zugzwang wrote: So you're ok

zugzwang

Maybe I’m being thick but I really don’t understand this comment. Help me out?

.

.

Still not sure what you were

Still not sure what you were driving at?

If you don't like Crimethinc,

If you don't like Crimethinc, you don't have to read Crimethinc. I still think that if you refuse on principle to engage with texts like Diagnostic of the Future then you're hugely missing out, but whatever, I'm not here to Fox in Socks you into liking them.

Beyond that, you seem really keen to turn this into a discussion of song lyrics, based on one single line out of the whole article. No-one is trying to set up some kind of anarcho-PMRC to censor unwholesome lyrics; the only reason I have much of an opinion about that Boots Riley line is because of that story about people chanting it in the street, because I do think we should hold chants on demos to a different standard than just some random hiphop lyric.

What the article is about, and I do think is worth discussing, is a whole culture of how leftists and anarchists express themselves, primarily online but with increasingly also in the real world, as is shown for instance by that Portland May Day event and that Seattle flyposter and that Jacobin cover and that demo in Virginia. Earlier you seemed to be denying that any such culture exists, now I can't tell if you're still doing that or if you've switched to admitting that it does but saying that it's totally fine?

.

.

OK, a lot to cover here, to

OK, a lot to cover here, to start out with the more relevant end:

zugzwang

I don't know what goes through Boots Riley's head when he's making his art and frankly it's not really any of my business. But if you can't see how that poster could possibly be interpreted as evidence that there are people out there who tend to express their politics in terms of a desire for bloody revenge... frankly I don't know what to say to that. Like, mixing things up a little bit, here's a meme page called "Gulag the Liberals". Does that seem fine to you, or is it at all concerning in any way? And if the latter, can you accept that there might be some kind of overlap between the people who are really really into gulag memes and the people who are really really into guillotine memes?

There's two things about that, one "internal" and one "external".

First, while I'm not an expert on the history of violence against landlords, mob violence against landlords sounds like the sort of thing that might have happened in, say, Spain '36, or the Soweto uprising, or something similar, the kind of thing that happens in unruly proletarian uprisings. Of course insurrection isn't defined by the amount of spontaneous violence against landlords, but it's not incompatible with it either. On the other hand, as the article spells out, the guillotine is a specific form of violence linked to the state that, from 1793 on, has been used by the ruling class against revolutionaries who threaten to get out of control. Do I think that it's a good idea to fetishise/glamourise any kind of violence? No. Can I see a difference between the kinds of violence that tend to erupt in insurrectionary situations, and the counter-revolutionary violence dealt out by a victorious state? Yes.

As for whether I'm complicit in the culture of violence and revenge I'm condemning, I probably am in some ways, I don't want to pretend I'm totally innocent on that front. But I try not to put that kind of thing front and center in terms of how I present my politics, which is quite different to how some other people approach it, as Reddebrek mentioned above.

Secondly, and probably more importantly, I'm not that bothered about "Let's Lynch the Landlord" because it's literally just a song. If there was a whole culture of people who made loads of lynching/mob violence jokes, and there had been a popular podcast called like "the noose" or "the lynching" or something, and Jacobin magazine had put a picture of a landlord being lynched on its front cover, and people chanted it on demos, then I might feel a bit differently about it.

zugzwang

OK, so this is perhaps even more of a detour, but I think there's a fair bit of cognitive bias at work here, I suspect that most of the things that you're getting angry at Crimethinc for are things that you wouldn't consider damning if they came from people you'd already decided you liked.

To run through them in order:

"pushing Bob Black and David Graeber as sources for understanding "anarchism"." - that same page also recommends reading Malatesta and Goldman, I see you didn't mention that bit though. As it happens, I'm pretty sure that the Anarchist Communist Group recently put out a podcast on abolishing work where they discuss Bob Black's ideas a lot (been a few weeks since I listened to it, but I'm 90% sure my memory's accurate on that). I was quite surprised by that, it didn't make me immediately write the ACG off for being lifestylist liberals or whatever though.

"promoting lifestylist campaigns like "Steal Something from Work Day" and so on" - I was going to say that Steal Something from Work Day seems no more or less lifestylist to me than the libcom office workers survival guide or the AFed "don't grass your class" design, but then I realised whoever runs the AF twitter page had gone me one better and was actively promoting Steal Something... Day. Like, obv it's not going to bring about the revolution, but as a small contribution to promoting a working-class culture of resistance and insubordination it doesn't seem totally worthless either.

"hosting history articles that completely misrepresent Marx and throw him in with Stalin" - yeah, Marx was contradictory, some anarchists like to stress the elements of his thought that pointed in the direction of working-class self-emancipation, others stress the negative aspects more. I'm not particularly interested in refighting the First International, but for instance long-term libcom poster Anarcho is very Marx-negative - does that make them a lifestylist or whatever as well? Admittedly it was Engels rather than Marx who wrote that awful letter on authority, but do we pretend like Marx wasn't on Engels' side against the libertarians in the international? Also, that same article quotes extensively from Makhno, Goldman, the Kronstadt rebels, Malatesta and so on, so whatever you make of their take on Marx, we're really not dealing with some lifestylist text about dumpster diving here. I think that, under any ordinary circumstances, if you saw a history text like that, or like "1919: When the Bolsheviks Turned on the Workers: Looking Back on the Putilov and Astrakhan Strikes, One Hundred Years Later", and it didn't come attached to a "brand name" you'd already decided you disliked, everyone would recognise it as being an expression of revolutionary class politics, no matter how unfair to Marx it might be.

""anarchism" (whatever that means to them because they never specify further on their faq page that they're communists etc.)" - they do mostly tend not to use the c-word. That's fine with me, there are a lot of people who oppose private property and wage labour who don't use that word and a lot of people who do use that word but don't have anything in common with what I would understand by it, so I don't really care if people use that word or not. But in their introductory text "To Change Everything", they define what they're against as "the problem is control, the problem is hierarchy, the problem is borders, the problem is representation, the problem is leaders, the problem is government, the problem is profit, the problem is property" - that sounds like not a bad starting point to me.

.

.

.

.

zugzwang wrote: Do I think

zugzwang

I think you're getting way too hung up on what people's subjective intentions are and not looking at what the overall impact of this kind of culture is. Like, even at this late stage in the game, I'm sure there's still some 4chan edgelords who are genuinely just doing it for the lulz when they post their helicopter ride jokes and would probably be really upset and distressed to witness an actual execution, that doesn't change the fact that they're contributing to a really harmful culture. And even if lots of the people who post guillotine stuff are similarly just doing it for the lulz, if the overall impact is to make people new to socialism/anarchism think that mass executions are an important part of the politics that they're learning, then I think that's a bad thing. I'm not going to lose a huge amount of sleep over it, but I do think it's good to have articles like this one pushing back against it.

Yeah, that article from nearly 20 years ago is bad, maybe you should email them suggesting they add a disclaimer. But also: if there was a group that started off by putting out articles like the one I've posted here, the one about the Bolshevik repression of strikers in Petrograd, their statement on the FSB bombing in Russia, their analysis of the McKinley assassination and so on, and then ended up putting out stuff like that Unabomber article, and some of the other crap they put out 20 years ago, we'd have no problem agreeing that they'd got a lot worse. Instead, the exact opposite has happened, and yet you don't seem able to accept that they've improved at all?

I'm not pro-murder, that's why I posted this article that you've put so much time and effort into rubbishing. But pointing out that these kinds of things aren't strictly necessary in a revolutionary situation doesn't mean that they're not going to happen. Lots of unnecessary, regrettable, counterproductive things happened in Brixton '81, LA '92, Greece at the high point of struggles there, England in August '11, Ferguson '14 and so on. More of them would happen in any larger insurrection. We don't have to approve of every single thing that happened in those moments to recognise them as proletarian uprisings, and to understand that there's a real difference between mistakes and horrible things that happen in the middle of uprisings and executions carried out by the state.

Although this is all pretty much a red herring: the main thing is that we can agree that, if there were such a thing as "lynch the landlord" culture, lots of lynching memes, a podcast called "the lynching" and so on, that would be bad, but no such thing exists, so I'd hope we can move on from that point.

Can you think of anything that's happened in the 20th century that might make people slightly less keen to use that word than they were when Kropotkin was writing in the 1890s?

But they clearly do put out articles from a revolutionary anarchist perspective, like the one I've posted here, or their account of the counter-revolution in 1919. They've also put their energy into calling for mass mobilizations against the border regime and Trump's state of emergency, antifascist solidarity demonstrations in the wake of Charlottesville, a solidarity campaign with J20, Standing Rock, and antifascist defendants, and to support and expand projects "confronting the opioid crisis, amassing supplies for the migrant caravans, mobilizing autonomous disaster relief, fighting gentrification and the housing crisis through community organizing, forming solidarity networks to take on bosses and landlords, building the capacity for self-defense through anti-fascist gyms, and coordinating health-care alternatives that don’t depend upon the caprices of the state." Like, you can slate some of that as being activism, but it's nonsense to call most of those things lifestylist.

.

.

.

.

Gordon Bennett. zugzwang

Gordon Bennett.

zugzwang

Do you ever get tired to trying to shoehorn in totally unrelated stuff? Once again, no-one has said anything against the DKs, McCarthy, Jonathan Swift or anyone else using gruesome imagery in their art as a way to critically depict the world as it is*; what has been said is that, if we take them at their word, then the people who consistently keep on using imagery of guillotines and gulags as part of their positive depictions of what they want to see - stuff like this, for instance:

Would appear to be motivated by some kind of desire for bloody revenge. Or, of course, maybe we shouldn't take them at their word, in which case it's surely legitimate to ask whether it's such a great idea to keep on generating so much propaganda which isn't intended to be taken seriously, which is only acceptable if everyone who sees it remembers to put ironic air quotes around everything they see.

* as it happens, I do think that there's an interesting discussion to be had around satire, irony and edginess, and what role satire and irony can play in a world that contains 4Chan, Boris Johnson and the likes of Sargon of Akkad and Count Dankula; but I'm not convinced that this thread is a good place for that discussion, and even less convinced that you're someone I want to have that discussion with.

I hope you didn't pull any muscles during that wild bit of reaching. I think it's pretty obvious to anyone who isn't going out of their way to come up with the most uncharitable reading possible that they're not about some extinction rebellion-type "solidarity with the police" shit; earlier in this very thread, you wrote that "Individual landlords themselves don't pose much of a threat... it's the capitalist State that ultimately defends their rights to exploit tenants. The same also goes for capitalists' rights to the means of production and exploiting workers." That is to say that you don't think landlords and capitalists behave the way they do because they're inherently harmful or bad people, but because of the state and capitalist social relationships, and that in the absence of those things they would behave differently. In other words, you have faith in the potential of ex-capitalists, ex-landlords and so on to one day be included in the human community that we want to bring about. That's good, it means that there's a clear difference between you and the "guillotine the billionaires, gulag the liberals" crowd, but it also means you obviously agree with the point being made by the piece of writing that you're flailing around trying to have a go at. I always really like the way Vaneigem phrased it: "Doesn't it give you a certain sense of pleasure to think how, some day soon, you will be able to treat like human beings those cops whom it will not have been necessary to kill on the spot?"

If you're that bothered by a decades-old Crimethinc article, perhaps you should write your own critique of it. If you're that interested in Crimethinc's policy about hosting old articles that may or may not contradict their current perspectives, you should contact them to discuss it. I can't say it's a subject I have any interest in. When I said "I would really recommend people read modern-day Crimethinc stuff rather than dismissing them on the basis of 2000s-era beef", I'm not sure what part of that you took as me saying "I really really want to reenact 2000s-era Crimethinc beef".

And by the way, you may notice that audiobook you found with the disclaimer links to this critique, which states "in several of the key areas at which our critique was aimed, particularly with regard to dropping out, CrimethInc. now state they have changed their views... seeing... the apparent improvement in their politics we no longer have any sense of antipathy toward them". But sure, they haven't improved at all, arguing against individual attacks like assassinations and for collective struggle is exactly the same as glorifying the Unabomber. Sure, fine, whatever.

That's the thing - if they totally disregarded and disagreed with all Marxist/ian analysis, and said that wage labour and commodities were actually great or something, I'd have a big problem with it; but as it is, if someone does take influence from Marxist/ian critiques, I don't really care that much whether they get them from Marx, Perlman, prole.info, random libcom articles or whatever. If you can engage positively with those kinds of ideas, which I think they do, but have a negative assessment of Marx himself, then at worst you can say that they're unfair to Marx as a person, which like maybe they are, but I don't think Karl Marx is going to lose any sleep over Crimethinc being mean about him.

The AF literally changed their name from the ACF because "Being associated with two labels, members of the ACF found they were spending more time convincing people that Anarchist Communism wasn’t a contradiction that they were discussing the real issues. Many thought that this was a waste of our energies and holding back the potential growth of Anarchist ideas here in Britain. Whilst we still hold on to our Anarchist Communist principles we acknowledge that first impressions count."

Similarly, the WSA are, if I recall correctly, the longest-standing US class struggle anarchist group, but I don't think they use the c-word at all. In my opinion, some of the best contemporary UK communist theory and analysis comes from the Angry Workers of the World, but shockingly enough their "about" page doesn't even use the a-word or the c-word.

It seems like whether or not someone says "anarchist communist" is a big deal to you; it's not that important to me. I don't see any correlation between how often someone says "communist" and how effective they are at advancing communist ideas. Anarchist communism says a lot about where someone stands with regards to the big debates of the late 19th/early 20th century; it doesn't say much about contemporary debates about post-revolutionary society (things like technology and ecology), and besides, you can have very similar ideas to someone about how post-revolutionary society can be structured but totally disagree on what counts as useful activity for revolutionaries right here and now, or vice versa.

Yes, quite a lot of things are hypothetically possible, especially if we choose to ignore all historical context about the way things have actually happened in the world. Maybe if a mob of rioters looted a Tesco and the Tesco sold fighter jets and the rioters were all trained pilots then they might all fly around in F-15s, why not?

.

.

.

.

.

.

dp

dp

Kind of agree with this

Kind of agree with this piece, although I think it is fair to recognize that in the heyday of Crimethinc's influence, they often glorified acts of essentially vengeful, individualist terror.

Also from some of the comments here, it seems some people aren't really aware of what happens on leftist social media and somewhat write it off as not relevant or not "real life". It's 2019. Most people in the US at least (maybe the UK too?) are on some sort of social media. I would say what happens on there you can no longer separate that from the life of actual organizations or scenes. For example, from my perspective arguably what moves and determines the North American IWW's internal politics happens in an unofficial Facebook group. Although not social media, how much have discussion here on libcom had a major influence in the internal politics of SolFed, IWA, IWW, anarchist political organizations, etc. I would say it has had a significant influence. You can't neatly separate the internet and 'real life'.

Yeah, I got very tired of

Yeah, I got very tired of trying to prove this phenomenon exists, but if anyone wants to discuss its effects, and how this kind of inflated verbal violence plays out in things like antifascist culture or the terf wars, I think that would be a discussion worth having.

.

.

Juan Conatz wrote: Also from

Juan Conatz

The West Virginia teacher's strike was organised to at least some extent due to a facebook group that ended up with tens of thousands of teachers joining it. Private and semi-private messaging isn't visible to those not involved, but it's taking the place of photocopied posters/newsletters and mass meetings to an extent. This isn't to say facebook groups are a great place to organise (I hate facebook) just to recognise that it's happening and contributing to mass wildcat strikes. This is a bit different to 'leftist social media' but it can't be completely separated from it.

Also it's a throwaway comment in this article, but the Trotskyist and Stalinist sects, especially but not only in the US, are struggling to survive now that members can quite easily find each other on twitter and facebook and communicate directly - most of them structurally or by decree prevented communication between rank and file members across branches. The ISO, WWP, and PSL have all seen splits or mass resignations in the past couple of years.

The Crisis and Collapse of the International Socialist Organization

Seen on Facecrack

Seen on Facecrack today

https://www.facebook.com/antifascistnews/photos/a.1464301610551693/2235686140079899?type=3&sfns=mo

Toronto mayday:

Toronto mayday:

That's some Grade A

That's some Grade A whimpering liberalism right there.

Very impressed

And another

And another one

https://share.icloud.com/photos/0AcnNcNpCaWm1K8z_xsGZJNHw

Ah yes, the notorious

Ah yes, the notorious whimpering liberalism of *checks notes* the Paris Commune.

.

.

zugzwang wrote: R Totale

zugzwang

Yes, because drawing attention to something that happened at a may day demo this month is exactly the same as getting bothered about a Morrissey song from the 1980s. For people who don't have gruesome revenge fantasies, do you think that kind of symbolism is a clear and useful way of expressing our politics?

Think people are concerned

Think people are concerned about Morrissey's open support for Anne Marie-Waters' For Britain these days.

.

.

zugzwang wrote: It makes

zugzwang

So I agree with a lot of this but there are two problems here:

1. A lot of people who are new-ish 'socialists' possibly via Bernie/Jacobin start out with this sort of analysis, and that's bad, but if they're genuinely interested in liberation they will (hopefully) find things and move past it.

2. Jacobin as a publication - Bhaskar Sunkara, Vivek Chibber, David Broder (formerly of The Commune), Dawn Foster, Micah Uetricht et al are stubbornly invested in having this analysis (various combinations of careerism and sectarianism would be one possible explanation) even though they know full well that more radical critiques exist.

So some people might be using the guillotine because they think that's radicalism and 'what a revolution looks like', but with the professional left it is a substitute for radicalism, a way of obscuring that their project is actually the management of capitalism.

zugzwang wrote: I think

zugzwang

I already responded to this. Using gruesome imagery or symbolism as a way to draw attention to issues or critically depict the world is not the same thing as putting forward the guillotine or gulags as a positive proposal.

I think we're in agreement here, because at this point you're not arguing against Crimethinc's perspective, so much as just restating it. I think the only remaining point of disagreement is your implied point that, because these people are confused leftists and not communists in the way you and I would use the term (agreed), they're not "worth taking seriously" and so it's somehow wrong to criticise them, when we share all kinds of spaces, both physical and virtual, with these people, and so we're required to take them seriously whether we like them or not.

Mike Harman wrote: So some

Mike Harman

Well put Mike, if only those moronic billionaires could be executed we professional leftists could manage capital rationally.

.

.

Thank you for reminding me

Thank you for reminding me that it was a bad idea to engage with you.

While I'm not sure if I want

While I'm not sure if I want to re-start this conversation, From Embers have just done a podcast exploring this argument further - not got around to listening to it myself yet, but probably worthwhile for anyone interested in the topic.

In other news, that Lana del Rey thing was undeniably really funny.

.

.

Zugzwang, your vendetta

Zugzwang, your vendetta against R Total is starting to look a little weird tbh.

As the for Twitter thing...

Really? I thought it was the capitalist system that did the killing? It looks really fucking stupid when anarchists appear as partisan in parliamentary politics. As well as being inaccurate, this comment gives a completely false impression of the anarchist position.

We all know the Tories don’t exist in isolation so being specifically anti Tory is pretty ridiculous. I don’t know who wrote this but I’d be interested to hear their explanation.

.

.

Interestingly it looks like

Interestingly it looks like it’s been taken down? I hope so.

I haven’t heard this band but considering their disclaimer they are clearly pretty stupid. Until recently their death to the infidel Tories wouldn’t have bothered me, I would just have dismissed it as inverse bigotry to be ignored or n the same why I’ve tried to ignore specific Tory bashing for the 35 years since I gained a little political awareness, but considering the recent rise in right wing violence inspired by social influencers I’d say it’s in pretty poor taste. MPs killed in a revolutionary context, well yes, if absolutely necessary, assassination within the current paradigm? Don’t be fucking silly.

Ah, but it’s just flaming, it’s just a joke. Try telling that to the trans people being fucked with by the viewers of the dank YouTube shitlords. I can hardly believe I’m saying this, I’ve been flaming the fuck out of people since I was a kid, but it now seems there are enough morons out there that we need to be careful what we say.

Right, better go listen to the song now.

Edit: Well, that was embarrassing. To be fair though, regardless of what I said above, I don’t see any danger in this, and you missed out an important part of their disclaimer...

This anti Tory thing is just so cringey though. It’s always good praxis to counter this myopic nonsense by dishing out Libcomer Phil’s anti Labour blogs in response.

Edit 2: Sorry, you did quote it right, my bad.

My position throughout has

My position throughout has been that I'm not in favour of censoring artists' lyrical content, not sure why you think that would've changed?

Anyway, I've not listened to them yet so I don't have a position on the really important question of whether the song's a bop or not, but as notes of general principle: we can, and should, extend solidarity to people who are targeted by media moral panics while also maintaining the ability to have our own criticisms of them - for UK comrades, a good analogy would be when once every few years Class War get in the papers, often for doing something relatively daft, we should be able to oppose Daily Mail hitjobs and the like without necessarily thinking all of CW's tactics are brilliant. As I understand it, it sounds like a similar situation's been playing out with the Toronto guillotine crew since mayday, and again we should "defend" them (whatever that means) against the media and politicians where possible.

Similarly, insofar as libertarian communists need to have a position on Tyler the Creator, I think we can oppose state bans without needing to claim that all his lyrical content has always been wonderful and none of it has ever been problematic.

Has anyone listened to that From Embers podcast? I'm about halfway through now, it's good so far.

Quote: My position throughout

Well yes, absolutely, but that doesn’t mean that lyrics are never effective in their aims, look at Screwdriver or the various US nazi bands. And there were plenty of libcommers working up a head of steam on the Death in June thread. However, the biggest problem with this particular song/vid is that the idea driving it is as cringey as fuck. I guess the only harm it will do is to convince libs and cons that anarchists are petulant self obsessed dickheads although even that is pretty benign - they think that already.

Yeah, I don't think this is a

Yeah, I don't think this is a massive issue or anything, and I'm going to have choose my words carefully here because one of those things I always go on about is how there's a difference between censorship and not giving someone a platform, but... obviously who gets to play Glastonbury isn't really anyone's business but the Glasto organisers, and if they'd just said from the start "this band is cringe and we're not interested in booking them" then that'd be fine, but for them to decide they wanted Killdren to play, and then turn around and change their mind on the grounds of journalists and politicians complaining, is a bit shit. I think "full solidarity with Killdren" is a reasonable response in that situation, the same as we can have full solidarity with Class War, or the Toronto guillotine crew, against the media while still having criticisms of them.

Having listened to the song, it's not that much of a bop, but I can imagine they might be fun live. Thinking about it, I do find myself with a renewed admiration for Ramshackle Glory actually managing to work the line "we can't blow up a social relationship" into a song.

Waste of time, but do you…

Waste of time, but do you not see that you, in your entirely unnecessarily long-winded posts, are just contradicting yourself and the article??:

Also,

Having listened to more Pat the Bunny than you apparently have, it's also worth pointing out some of his more "violent" lyrics, such as "I dip this pen in arsenic and write a song for every president who won't ever get shot in the face" and "gotta hang those crackers who lynched Troy Davis" and "take your car up to Oro Valley and burn every store I can find." It's almost as if understanding that "we can't blow up a social relationship" doesn't also mean that you can't still use violent imagery in your music or art in order to get a point across.

I mean, I don't really…

I mean, I don't really remember that much of what I was saying back in 2019 and was pleasantly surprised to see how much of what I was saying I still agree with. I don't think anything I've said was particularly contradictory, and if we're going over posts of mine from almost five years ago, how about this bit?

"Beyond that, you seem really keen to turn this into a discussion of song lyrics, based on one single line out of the whole article. No-one is trying to set up some kind of anarcho-PMRC to censor unwholesome lyrics; the only reason I have much of an opinion about that Boots Riley line is because of that story about people chanting it in the street, because I do think we should hold chants on demos to a different standard than just some random hiphop lyric."

And, fwiw - "For this is what distinguishes the fantasy of the guillotine: it is all about efficiency and distance. Those who fetishize the guillotine don’t want to kill people with their bare hands; they aren’t prepared to rend anyone’s flesh with their teeth. They want their revenge automated and carried out for them. They are like the consumers who blithely eat Chicken McNuggets but could never personally butcher a cow or cut down a rainforest. They prefer for bloodshed to take place in an orderly manner, with all the paperwork filled out properly, according to the example set by the Jacobins and the Bolsheviks in imitation of the impersonal functioning of the capitalist state." - I don't think that there are any Pat the Bunny lyrics that express the desire for executions to be carried out by a revolutionary state, which as the article highlights is fairly central to the image of the guillotine.

But nice to know my comments make such an impression on people years down the line, anyway.

For what it's worth, I don't…

For what it's worth, I don't particularly care for the use of guillotine imagery on the left either; I think it's gruesome and historically problematic, as the article discusses. However, I wouldn't go around claiming that guillotines are "state tools" that are doubly bad "because the Nazis used them as well." I'm not sure what makes guillotines a "state tool" to begin with or what prevents revolutionaries from employing one if they really so desire and as they already have. My issue is more with this,

Who?? Who wants “uncompromising bloody revenge”? Do the authors really think that someone pushing around a guillotine shopping cart at a demo, or donning guillotine earrings, actually wants to kill all billionaires? Or is it more likely that the authors of this text are just fear-mongering over entirely innocuous stuff? What does Crimethinc also want people on the left to do? Censor themselves and never include violent imagery in anything they do (as if Crimethinc’s website weren’t chock-full of far more violent content itself)? I also fail to see how Crimethinc's pearl-clutching is any different from the British media types who stoked fears over Killdren’s music (which was especially funny when their actual message was that people should vote against the Tories). It would be a different matter if Crimethinc were critiquing specific people’s ideas—such as people who actually desire “uncompromising bloody revenge”—but it seems like the article is more interested in policing what people say or do, which is something I disagree with.

Furthermore, Crimethinc are just hypocrites. They publish pieces like this condemning guillotine and other violent imagery on the left while also selling a text on their website that openly praises the Unabomber, and which they continue to describe as their “flagship book” and “Crimethinc for beginners.” Here’s Days of War, Nights of Love:

A group that glorifies a serial murderer and reactionary like Ted Kaczynski is in no position to be handing out lessons about what is and isn't appropriate for people to include in their art or demos. There is no excuse for continuing to host and sell such content. If your views have changed, then you purge these earlier writings from your website, or at the very least add a content warning, of which there is currently none.

You seem a bit confused…

You seem a bit confused about the distinction between critique and policing?