The history of an unwaged workers' group in 1980s London, its efforts to establish and run a centre for the unemployed and its relationship to the Miners' Strike and other struggles of its times.

Note: this is the text from a pamphlet produced in late 1987 by the Campaign for Real Life. The pamphlet was more interesting as it included more examples of the group’s leaflets and posters, and newspaper articles.

The text has not been changed, except for spelling mistakes, even though the writer’s views have changed over the past 20 years.

===========

UNWAGED FIGHTBACK

A HISTORY OF ISLINGTON ACTION GROUP OF THE UNWAGED

1980-86

1) SETTING UP

In October 1980, workers from Islington's welfare rights organisations, and one local unemployed man got together to try to set up an unemployed group. Unemployment was rising rapidly and the welfare workers felt that just telling the unemployed their rights was not enough - that something had to be done to extend these pathetic rights, and they recognised that this could best be done by the unemployed themselves.

Unemployed groups were forming in various parts of London, and someone from the Greenwich group, which was already active, was invited to speak at the inaugural meeting. The meeting was organised at the Co-op Hall and the dole office nearby was leafleted for two weeks before, with new people gradually joining in the leafleting.

About five new people turned up to the meeting, plus a guy from the NF who was quickly thrown out. It was decided to start meeting weekly, to try to get more people involved, and to try to get up a centre for, and run by the unemployed.

But despite the belief that unemployed people had to organise for themselves, it wasn't until some months later that the group was angered into taking themselves seriously, and taking control of their dealings with the authorities. Up till then they'd sat back and watched the welfare workers deal with the council, trades council etc. -they seemed to know what they were doing, while the group had no experience and were intimidated, less by authority than by all the forms, codes, behind-the-scenes deals etc. Instead the group was just trying to keep going, believing that when they got the centre they could take control. They were leafleting, flyposting and meeting, new people were joining, and a few dropping out.

Then in April there was a meeting in the area organised by the South East Region TUC (SERTUC) to talk about unemployment and setting up a centre. Most of the group were there, sitting at the back, listening to how the bureaucrats were going to set up a centre, how they'd been doing lots of things for the unemployed, but the unemployed weren't interested, and so on, until finally the group started shouting that they were organising for themselves. The union hacks weren't interested and didn't like their meeting being disrupted by plebs. The welfare workers said nothing.

The next meeting with SERTUC was on better terms - one of them among a conference of the London & South East Federation of Unemployed Groups. He was there to sell the TUC/government line on unemployed centres he failed. Nearly every group there totally rejected the guidelines, the imposition of paid, workers, and political control. The SERTUC guy felt so rejected he was desperate for friends, and after a few kind words on the way out, he agreed to write some nice letters for IAGOU. This was June '81. The conference had been set up by the Greenwich and Southwark groups and was attended by 16 militant groups. There was a feeling that things were just starting, that the movement was going to grow, and be a vehicle for real change. Brixton and St Pauls had exploded - in many areas the cops were careful not to provoke more trouble, and people on the streets were becoming confident. Mass unemployment was something new, at least for white males, and included many who were looking for a lot more than a job. Unemployment and the riots seemed to be the crack in the system that people had been waiting for.

A week later there was a national conference in Leicester, with over 80 people from 25 unemployed groups, plus individuals and some union reps. Everyone was excited at going national, but the question of how to organise caused major arguments. Leicester and most of the other Midland groups were controlled by Socialist Organiser (a trot group in the Labour Party) who had met a couple of weeks before to organise their position. The constitution they came up with was centralised - the conference would elect individuals onto a committee which would run the 'union'. Their proposals were sent out a week before the conference, and IAGOU immediately prepared an alternative. They argued that electing individuals was absurd because they might get jobs or drop out, or their group might disband or conflict with them, leaving them outside the real movement. They wanted local groups to be the basis for organisation, and the structure to be kept as informal as possib1e to allow each group and individual as much input as they wanted. Instead of creating a committee to decide what should be done, IAGOU wanted a structure where each group could come up with ideas for struggle, and develop them with the others. And there was deep suspicion of giving an individual a position from which to speak 'on behalf of' the unemployed or to impose a political line, as S.O. seemed to want.

IAGOU took their proposed constitution to the conference and handed round. Most of the groups not controlled by S.O. called for the decision on the constitution to be postponed as they had not had time to discus the new proposals and had no mandate on them. IAGOU agreed, but when a compromise was put to them at lunch, they copped-out and withdrew their proposals. So a committee was elected, and before long the organisation was in the hands of a few people - or at least the name was, the organisation ceased to exist when everyone went home. Still, IAGOU came back inspired by the fact that the movement was national, whatever a particular organisation might do, or fail to do.

Meanwhile, conditions in the dole offices were getting intolerable. The rising number of unemployed was not matched by an increase in staff or facilities, meaning long queues, crowded dirty offices and stress on both sides of the counter. Added to this, the staff were taking action over a pay dispute, which closed down various dole and DHSS offices. IAGOU supported the staff, practically organising the strike at one dole office, giving out union leaflets to explain the dispute to other claimants, but they also put forward their own demands for improving conditions, particularly at the Medina Road dole office.

On July 7th IAGOU held a public meeting near the dole office, and the next day held a demo. They wrote their demands on a chalkboard outside the office, and painted slogans on the pavement where the queues ended - some of them quite a long way down the road. Then they went in, about 50 of them, but the office was already packed and it looked like everyone was demonstrating. A couple of them got up on the counter (this was before shatter-proof screens) and started shouting out their demands and calling for the manager. Both claimants and staff showed support, so eventually the manager agreed to meet a delegation. She was totally patronising and obstructive (not knowing that one of the delegation was an unemployed councillor) but gave in to some of the demands;

Some notices were put up in Urdu, Gujerati, Greek and Turkish. but this only lasted a few weeks.

- A toilet was made available to claimants, but only in emergencies (as defined by management)

- A slip was sent out with giros saying when to sign on next.

- An extra bench was put in, for two weeks.

- some replacement giros were handed out over the counter instead of being posted.

a few more staff were taken on, but nothing like the 22 lacking according to their own calculations.

Another public meeting was held shortly after, followed by another demo about the continued delay in receiving giros. About 70 claimants took part. When somebody shouted out 'What are we supposed to 'do pawn our gold jewellery?' the manager replied 'well, you can pawn your furniture' which did nothing to calm the situation. IAGOU demanded another meeting. At first this was refused, but then a date was set for July 24th. To avoid any ‘trouble’ Regional Management made the manager close the office for the whole day creating even more chaos and aggravation.

At the same time, IAGOU had been contacting unions and the council to try to ensure that claimants were not cut-off or evicted due to delays in payment caused by the strike, and were successful. They also went over Hackney, to demand emergency payments from the council, and the council agreed immediately, rather than have hundreds of angry claimants while the riots were in full swing. If you were willing to queue up twice you could get two payments, or more. While there, IAGOU helped a Hackney unemployed group get going.

With the end of the strike much of the chaos continued, and some improvements were taken away again by management, so IAGOU held another demo on August 24th, again at Medina Road. But eventually the chaos was reduced by the opening of another office nearby. and the introduction of monthly signing instead of two-weekly.

In this period of chaos, IAGOU brought out their first newsletter called U B Press. It included articles explaining the situation and struggle at the dole offices (with ½ page by one of the workers), proposals for setting up a centre, a section from a book by Wal Hannington (unemployed leader of the '20s) on the occupation of an Islington library as an unemployed centre in 1920, reports from the two conferences, and more. And all for only 2p!

There was also a benefit at which everyone had a good time and IAGOU made 70 quid. It was called Bop Against YOP, but unfortunately those affected by the Youth Opportunity Programme, 16-18 year olds, couldn't get in as it was held in a pub that the cops kept their eye on.

On October 22nd Norman Tebbit, Secretary of State for Employment (as they say in Newspeak) visited Barnsbury dole office in South Islington. Informed of the visit by a mole, IAGOU organised a demo to welcome him, and sent out a press-release. When it arrived, Tebbit was jostled by a crowd of about 30, hit by an egg and chased into the building. “ .... the egg was thrown from two feet away, hitting him on the crown of the head. It burst and the yoke (sic) dribbled down his neck onto his clothing.”(the Times) "A spokesman for the Department of Employment said, 'he was not hurt."(Morning Star) Because of the press release, it was attributed to IAGOU, which upset the SWP because the egg was actually one of their members.

Relations with the SWP were not particularly good anyway. During the civil servants' strike, IAGOU and the local SWP branch organised a joint meeting, except that the SWP had organised it as their branch meeting, at which they told IAGOU to disband and join the Right to Work Campaign – one of their front organisations, which they disbanded about a year later. Then IAGOU tried to discourage a bunch of local SWP students and lecturers from trying to occupy a Job Centre ‘as a stunt’. They went ahead, gave out a few leaflets, were ignored, and went to the café.

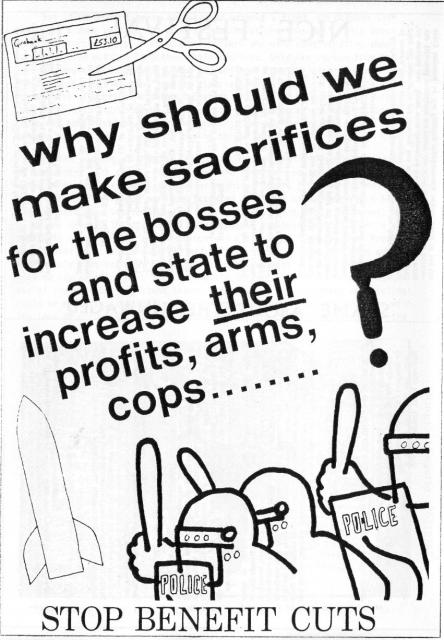

IAGOU poster

2) THE FIGHT FOR A CENTRE

One of the main aims of IAGOU from the start was the setting up of a centre for the unemployed. The most obvious way to do this seemed to be through Islington Council and the Greater London Council. They were both willing to fund 'community groups', especially when they expected political support and good publicity in return. Also they had property to spare. But of course it wasn't as easy as going along to the council and saying 'we're unemployed and we want a centre'. There were forms to fill in, bureaucracies to deal with, support to be lobbied for, internal politics to deal with and constant pressure to apply, to force action instead of just words.

Getting them to accept that the centre would be run and controlled by the users was at that time comparatively easy. To start with it was a lot cheaper for them not to have to pay for workers. Also at that time the only existing model for unemployed centres was the MSC/TUC guidelines which were not particularly acceptable to any of the parties involved; the council were not keen on the lack of campaigning imposed, because they expected that any campaigning would be effectively pro-Labour, the unions were against the MSC rates of pay, and IAGOU were against these, and the control being in the hands of the various authorities. Both Islington Council and the GLC liked to appear radical, and anyway they would have control in the long term, through controlling the purse strings.

In May ‘81 the council agreed in principle to funding a centre, and IAGOU had to go away again and produce detailed plans and a budget, which was a bit hard without having a building to base their plans on. The council were not particularly helpful over this, but eventually IAGOU found an empty council-leased shop and decided it would be the centre. It was at 355 Holloway Road on one of Islington's busiest roads for shopping and traffic, almost in the centre of the borough and close to Medina Road. It had been empty for some time since being used as a housing advice centre. The lay-out and conditions weren't particularly good, but they were told money would be available for alterations and improvements.

In June the council's Employment Committee agreed to give the group £4,000 to equip the centre, and by September Finance and Planning had approved the handing over of funding and the building 'as soon as possible'. The Valuers, Architects and IAGOU drew up plans for the alterations and in November the Solicitors approved the group's constitution, after long arguments and delays. In December the money for equipment was handed over, and it looked like the keys to the building would follow shortly. They didn't.

In the new year, the majority of councillors either suddenly ‘saw the light’ at the same time, or else found a way to do what they had always really wanted, but without joining the Tories - they went over to the newly-formed SDP. Overnight the Labour stronghold became the SDP’s first taste of power, without an election. Those who had been spouting the Labour line could now do openly what they had only done secretly or negatively before. Grants were axed, staff vacancies frozen, plans made to increase rents and sell off 750 homes. A worker in the housing department was victimised, and nearly all the council workers came out on strike. On February 9th the Employment

Committee met for the first time under SDP rule. They agreed to fund the local Chamber of Commerce to the tune of £16,500, and refused the £7,000 previously promised for the centre, and so the centre itself. According to the council leader, 'A centre for the unemployed in Islington would only encourage people to stay on the dole'. Most of IAGOU were at the meeting, and some had to be physically removed. That night the town was painted red, with demands and threats. The next full council meeting had striking workers, threatened tenants, IAGOU and others demonstrating outside at the start while inside the meeting had to be stopped at least once, due to screaming, chants of 'Unwaged Fightback' and rolls of bog paper flying from the public gallery.

As a (not very successful) publicity stunt a few of them went down to the first SDP national conference at Kensington Town Hall. Two of them got in with borrowed press cards and borrowed clothes, and were meant to let the others in through a side door. They couldn't find a side door, but anyway they hung out a massive banner, which had been cleverly disguised as journalistic fat and shouted a few slogans and insults before being led out very politely. All the press were there, but only one of the local radio stations bothered to mention it.

Before the SDP had come along, IAGOU were already getting sick of waiting, and were making plans to occupy the centre instead. They told the Employment and Valuers Departments that they needed to look over the centre again to prepare the next year’s budget and other things. Both departments said it would be alright, but due to illness and holidays neither could send anyone along, so IAGOU would have to pick up the keys and go on their own.

So on a Friday there was a special planning meeting to sort out all details, the weekend was spent at the local resource centre printing leaflets and posters to publicise the occupation and Monday the shopping was done, bog paper, tea etc, and everything was set for Tuesday. But late on Monday the head of the Employment Department rang, saying ‘what happened at your meeting on Friday? We know you planned something for tomorrow, what is it? I need to inform the councillors’. Of course he was told it was none of his business and as they didn't know how much he knew, the plans went ahead.

The key was picked up with no problem, and everyone was in place across the road in Sainsburys, a few cycling up and down the road and the rest in a cafe up the road, plus 12 from the Student Union were waiting at their college round the corner. But the building had been boarded up and a cop was standing outside. The worst thing was not knowing who had grassed - everyone was under suspicion so it was impossible to try again. One of the people at the planning meeting was involved in setting up another unemployed project mainly for basic training which was also after funding. He never came to another meeting.

Council elections were due at the start of May, and the Labour Party promised the keys to the centre ‘within 24 hours of getting re-elected’. This didn't make IAGOU rush round campaigning for a Labour victory, but the campaigning they were already doing, along with all the other struggles going on, must at least have given the impression that things had been, and would be slightly better under Labour.

Anyway. Labour got back into power with only a few of the defectors keeping their seats. The next day the Labour leader said that IAGOU could the keys the day after they officially took office, a week later. Nothing happened. One problem was that shortly before the election the council sold off the lease on the property, but the new lessees were just speculators and gave the council a sublease. It was the freeholders, who the council had supposedly dealt with months before who kept being a pain. Meanwhile the council kept raising questions that had been dealt with before the SDP took over but after a lot of pressure the centre was finally handed over in August ‘82, over 3 months after the election, and over 11 months from the first promised date.

3) A CENTRE FINALLY

The idea that once the group had a centre as a base, they would be able to consolidate and really start moving was soon shown to be an illusion.

The centre was there, but it didn't run itself. Whereas before they were running around without a base, now they found they couldn't run around so much because they were stuck holding the base. The centre had to be open every weekday (the fact that for a while it wasn't was later used as an excuse to close it) so people had to be there even when nothing was going on. Idiots who wandered in had to be treated sympathetically. Receipts had to be kept for every pen bought. And possibly most destructive, the building alterations had to be arranged.

The building was made up of two rooms, plus the toilet. The front room was long and thin, with a lot of space taken up by the entrance, which was a sort of glass passageway leading up to the door. This was intimidating and stopped a lot of light. The back room was square and housed the crèche, TV and cooking facilities. The back wall was damp and collapsing, and each time it rained the damp spread another inch across the floor.

The plan was to make the front straight, re-divide the rooms more evenly, close off the cooking area with a serving hatch, add a disabled toilet and a couple of room dividers, and generally do the place up. The effect would have been to make the place attractive, safe, and spacious enough for various things to go on at the same time.

First they had to work out what they wanted, then the architects and builders were brought in to draw up proper plans and estimates. The GLC then had to agree to fund the work and the council had to give planning permission. And once all that had been arranged, and it took a long time, the head landlords decided they didn't like it, and wouldn't allow it. It was discovered that they could be taken to court for being unreasonable, but this had to be done by the council as sub-lessees. The council thought about it for a couple of months, and then said they would do it if the GLC would cover any legal costs. The GLC thought about for a few months, and then said no. So after many months of hard work, the group were left with a damp, dingy intimidating building.

Still, it was there, and people dropped in, for advice, to watch films, to join the campaigns, the occasional workshop, the meetings or just for a chat or for-curiosity.

IAGOU had its meetings on Thursdays, and Wednesdays were Wageless Women day. Islington Wageless Women had been meeting for over a year, organising women's events, campaigning against the cohabitation laws, for nurseries etc. a London & South East Wageless Women conference, exhibitions etc. and intervening in IAGOU and the rest of the movement, to struggle against sexism and illusions. In terms of theory Wageless Women were far more together than IAGOU, but when it came to practice they had greater problems. They didn't want to be an 'unemployed' women's group, but based their analysis and struggles on the role of women in the reproduction of capital - on the unwaged work that women are trained for from birth, and perform every day whether they also do waged work or not. Their basic demand was for a guaranteed minimum income for all, to allow women (and men) more choice over what work they do, and giving women independence without them having to take on waged work as well. They criticised IAGOU for basing their campaigns around the dole office, which excluded many unwaged people not signing on as unemployed. This was correct, but the problem then was where else to organise. IAGOU's best struggles were waged at the dole office, because there were already large numbers of people there - something would have happened there anyway, without IAGOU. To have used the centre for organising all unwaged sectors of the proletariat would have required far greater organisation, publicity, imagination and resources than they had. Of course they could have tried harder, but while accepting the criticism, and making the Centre open to all the unwaged, IAGOU remained essentially an unemployed group.

The change of name from Islington Action Group on Unemployment to Islington Action Group of the Unwaged, which happened around the time the Centre opened, caused disagreements with various authorities. The change meant not only a change in who could be involved, extending outside the terms and analysis of the 'Labour Movement', but signified also a change in self-definition; instead of defining themselves in terms of jobs (ie not having one) they defined themselves in terms of resources (ie not having any). Of course the two are directly related, but the point was to try to change this - to end the poverty - while pointing out the historical (and so changeable) reasons for it. The poverty of the dole is a tool to enforce work - we work because 'we have nothing to sell but our labour', but to some extent we choose what conditions we will work under. Mass unemployment and benefit cuts restrict our choices - they restrict our ability to struggle over conditions through the need to keep, or get a job. So instead of joining the campaigns for jobs, where the unwaged were treated as the 'reserve army' of the labour movement, IAGOU struggled to improve their conditions as unwaged people, and so improve their (and others') choices, alongside the struggles of the waged. But the struggle was meant to go beyond merely improving conditions, a constant struggle with more or less success according to conditions;- it was meant to strike at the basic poverty of our class, on which our exploitation is based. The resources of this world that we have created have been stolen from us, and we can only get the means to a decent survival by selling our labour power, to be used by the bosses and state to produce more riches and means to exploit us. This exploitation can not be dealt with by demanding more of it, but by attacking its roots and its myths. We now live in a world where the bosses can only continue to impose their role, to impose labour and poverty on us, through creating artificial shortages, through destroying part of the abundance we produce and leaving the means of production to rot. The abolition of labour is the task before us, the appropriation, by all, of our products and means of production, which no longer require our sacrifice.

Stickers

4) CAMPAIGNING

The first major campaign run from the Centre was against the Specialist Claims Control Unit (SCCUM), one of the specialist fraud squads sent round different DHSS offices to intimidate claimants into signing off. They tend to pick on single parents (who they accuse of cohabiting), people with skills that 'could be used off the cards' or whoever's name comes out of the hat. Like the SPG, their name gets changed regularly to put off resistance.

In October ‘82 the SCCUM were sent into Archway Tower, home of Highgate and Finsbury Park DHSS offices, and a large demonstration was there to meet them. As they arrived they were photographed, and their pictures and car numbers flyposted around the area, with advice on how to deal with them. This was also put on the front page of the local alternative paper. They have met similar resistance in most other places, and the ordinary DHSS staff will often walk out for the day when they come, and refuse to co-operate with them. Bethnal Green Claimants Union were so successful at disrupting their visit to the area, that one of the claimants was taken to court for 'intimidation', but was quickly found not guilty. Outside the court the SCCUM were further 'intimidated' by having a camera pointed at them, so they ran off down the road with the lens-cap! It's interesting how such anti-social elements project their own obnoxious habits onto those at the receiving end - a primary symptom of paranoid schizophrenia. A claimant was once being harassed for ‘suspected cohabitation’ and asked IAGOU for support when the fraud officer came to visit. When he came in and saw a group of people with a tape recorder, he asked her 'don't you regard it as a private matter?' as though IAGOU were the ones interested in her personal relations.

Then came the struggle against race-checks at the dole office. Staff were to be ordered to fill in a computer form for each claimant, marking them down as;

1)African/West Indian

2)Asian

3)Other

4)Refusal (claimants had the right to refuse to be assessed, but the staff were not allowed to tell them that they were being assessed, making this 'right' pretty useless. The reason for this was that in test runs, they found that more people refused to be assessed when they'd been told about it than when they hadn’t!)

Only 1, 2 & 4 would have been marked on the computer, in other words only if you were black or bolshie enough to refuse would you have a mark on your file - a mark identifying you for the fraud squads when looking for someone to harass or for anyone else with access to the computer.

The Department of Employment claimed they only wanted statistics, and for this they were supported by parts of the race relations industry who wanted to show that black people are discriminated against in employment. But anyone who didn't already recognise this fact would be among those, journalists, government ministers etc, who would no doubt use these same statistics to 'prove' the opposite - portraying black people as 'scroungers', as the problem. Employers are the problem so they're the ones who should be hassled and assessed. Race statistics have always been used to promote racism, never to fight it.

In March '83 IAGOU produced leaflets on the checks, including a tear-off slip to hand in when signing on. saying 'please note that I refuse to be monitored for my ethnic origin,'. At this stage the government postponed their plans, but by the end of the year it seemed they were ready to try again. So after a lot of leafleting, flyposting and visiting other groups, the inaugural meeting of the Islington Campaign Against Racist Checks was held at the Centre in December, with guest speakers from the Black Healthworkers and Patients Group and others. The turn-out was appalling - most of the black groups contacted had said-good luck, but had their own agendas of struggle and many people leafleted outside the dole offices expressed anger but felt nothing could be done until the checks started - and the campaign remained the work of IAGOU. The publicity continued, including a live interview on Radio London, and soon the campaign spread, so that in February ‘84 the London Campaign Against Racist Checks was set up, made up of unwaged groups, dole staff and others. Much of that summer was spent leafleting at various festivals, and the meetings, when held in Islington, would often go on till the early hours of the morning (but business was always finished in time to pop over to the pub) and generally campaigning was combined with having a bloody good time.

In August the government decided to have a test run of the checks at various dole offices – they had already done test-runs so it was obvious that what was, being tested was the amount of resistance. Demos were held at Holloway, Pekham and Brixton dole offices when the tests were supposed to be carried out there. About a year later they tried again - again there were demos-and a one-day strike by the staff. Another year on they tried it in the Job Centres, where for many reasons people felt less threatened by it so there was little resistance, but now that the Job Centres and dole offices are to be re-merged, the struggle is being taken up again.

At various times there were attempts to campaign against the Youth Training Scheme etc, against benefit cuts, and for concessions at council sports facilities - (successful) and at cinemas, Arsenal, public transport etc (unsuccessful). Some fun was had at a show put on by the government as part of their 'review' of benefits. They held a public (though practically un-publicised) series of discussions between representatives of the government, business and a few liberal organisations. The result of this farce was a foregone conclusion, so IAGOU and some of the Claimants Unions booed the show off stage, drowning it out with whistles and loud conversation. Unfortunately the performers were allowed to leave the stage unharmed despite being outnumbered.

The question of how to effectively campaign over the level of benefits, our standard of living, was always a major problem. Obviously the unemployed (as opposed to other sectors of the unwaged - ie 'housewives') are not in a position to strike, but can still be very disruptive to the system. Our current level of income is due in part to past disruptions, and the state's attempts to avoid them in future. What would most encourage the state to increase benefits would be a situation where large numbers of the unwaged (and waged) were already directly taking more, through mass looting, mass fare dodging, rent strikes etc. in which case demanding increased benefits would be irrelevant - the important thing would be to extend this real power instead of legitimising the state by making demands of it. On the other hand there is the possibility of waged workers taking up the demand, especially when fighting redundancies, but IAGOU do not seem to have directly suggested this to any workers. Instead the idea of an increase, or of a Guaranteed Minimum Income were used in effect as a way of explaining other campaigns and struggles (we should get more/a GMI because... so we're demanding/doing X) or as an alternative/opposition to the demand for jobs. Meanwhile they encouraged shoplifting, benefit fraud, squatting, careful tampering with meters, eating the rich etc.

5) CHANGE OF MEMBERS

By the first anniversary of the Centre's opening there was only one person left running it, it was opening very irregularly and there was no money as the GLC grant was late as usual. Some people had actually found jobs while others had just got sick of putting in a lot of work for little return, and waiting for funding to come through, or had their time taken up with other struggles. Fortunately two new active members turned up within a couple of months and helped get things going again, while some of the less active members returned once the Centre was opening regularly again. But when the last of the original activists left, in early ‘84, all continuity had been broken. The new members had to gradually discover the group's history, contacts in other groups etc, and deal with the bad relations inherited from past disputes. Having not taken part in the long struggle to get the Centre and funding, the new members tended to take them for granted, and took the threats from the council and GLC less seriously than they should, while they also lacked the experience of fighting these authorities. And as they had not been part of the original collective process of deciding what the Centre was for, and because of the need to get more people involved, they often felt unable to impose their views on those who wandered in, meaning that at various times the place was a centre for local kids to wreck, or for the propagation of ultra-leftist ideology, or whatever. The film-shows, which were originally chosen for their political and social content, to encourage discussion and activities, degenerated into showing whatever it was felt would attract the most people, although the best attended showings were actually on Nicaragua and the Amsterdam squatters riots. Also there were the ever-present problems - that the activists became a group of friends who tended to mould the centre and its activities around themselves, making it more accessible and attractive to their friends than to the majority of the unwaged; that the smallness of the group always limited its actions, so putting off more people from joining in; and of course the many people who came along expecting someone to fight for them or organise them. But through the Centre being constantly kept open, and through constant campaigning and events, new people were attracted and the problems gradually confronted (to return in other forms).

By the summer of '84 the Centre had again become a real centre of activity, with the campaign against racist checks leading to meetings and actions all around London, the miners strike, with miners using the Centre as a base, and the group doing collections and visiting some mining areas, and the start of threats from the GLC leading to trips to County Hall to graffiti counter-threats and leaflet their festivals, and many other things.

But as the racist checks were postponed and the GLC threats went slowly through the bureaucracy, so losing their immediate importance, what was left was the political line and posture the group had taken on the miners' strike. This, along with the political affiliations of the two main activists had attracted a few ultra-left politicos from outside Islington, and for a while all that came out of the Centre was propaganda that had little direct relevance to the unwaged of Islington.

Meanwhile, another centre had been open for sometime in Islington. Molly’s Cafe was a squatted centre in Upper Street, about a mile away from the Unwaged Centre, with a vegetarian cafe and various activities. It had been started mainly by punks who had been involved in previous squatted centres, the 'Peace Centre' in Roseberry Avenue, the anarchist bookshop in Albany St etc. and in 'Stop the City'. For some time the two centres ignored each other, IAGOU sinking into isolation in its centre and opposed to the anarchism of Molly’s, while the Molly’s crew were put off by their expectation of another council-run community centre. But eventually they got to know each other and started working together – the Tavistock Square Claimants Union was set up at Molly’s with publicity printed by IAGOU, together they set up the Islington Housing Action Group, and a day of videos, speeches and discussion on Ireland was jointly organised at the Unwaged Centre.

It was the day on Ireland that finally brought to a head the dispute between the ultra-leftists and the other users, including the activists from Molly’s. In political terms the dispute was over self-organisation: in principle both sides were for it, but for the ultra-leftists this meant producing propaganda attacking manipulators, forms of organisation that restrain struggle, recuperation of struggle etc, so that the Centre and its resources were there for them to use as they saw fit, as representatives of this ‘correct’ ideology. But for the others the resources were for the direct self-organisation of the unwaged (and others) irrespective of political position, for developing our struggles according to our experience. Two of the ultra-leftists in particular were making the atmosphere unbearable - one was constantly critical of everything without any positive suggestions and easily wound up to a tantrum, while the other took pleasure in winding him up, hid the best paper for his own pamphlets, ignored most of the people coming in, and finally wrote stupid graffiti across a poster in the window for the day on Ireland, having made no attempt to take part and so express his views constructively.

At that time the weekly meetings had again stopped, as IAGOU as such was not doing a lot, except with the people from Molly’s who, although they were using the Centre more and more, had not got directly involved in running it. To break out of this rut, a package was put together and put to everyone involved - expulsion of the two disrupters, and new activities for the Centre with meetings again. A special meeting was held for the expulsion and the result was a forgone conclusion, the expellers having organised the invitations to the meeting. One of the expellees recognised this and didn't turn up, having paint-bombed the front of the Centre the night before in protest, but the other tried unsuccessfully to justify himself. A new issue of Unwaged Fightback magazine was started and various activities organised to defend the Centre and restart campaigning, which gave new life to IAGOU, but with a new, informal power structure based around a few of the activists who were moving into a squat together.

6) MINERS & OTHERS

1984 was the year of the miners' strike, and IAGOU, like many other groups, joined in by collecting money etc, joining pickets and demonstrations, and encouraging solidarity among the unwaged (and waged) of the area. Two groups of miners used the Centre at different times, as a base for organising collections, meetings and trips to speak to other workers - first from a pit in Staffordshire, and when they found a less chaotic (and more officially approved of) base a branch from Sunderland moved in. The money collected by IAGOU went, at various times, to these two groups, to strikers at a Nottingham pit, a Women's Action Group (mainly miners' wives) in Derbyshire and to the families of miners imprisoned for their part in the struggle. This was always organised directly, rather than through official union channels - when the Staffordshire lads were met on a demo in the early days of the strike, their regional union treasurer was supporting the scabs and refusing to pass on money to strikers, while towards the end there was the fear of the money being sequestered, but the main reason was that the group wanted direct links, so that ideas and experiences could be shared, and so that the miners would know who the solidarity was coming from and why, rather than it appearing to be the work of the union bureaucrats. Collections were held at least once a week outside Sainsburys, two jumble-sales were held, and a large window display (made famous by the Islington Gazette) encouraged passers-by to come in and donate. One guy who came in said that he had just been interviewing Margaret Hodge, the council leader, and the only way he felt he could make himself clean again was by donating a fiver to the miners. An attempt to collect toys for miners' children for Xmas failed, but food and money were donated instead, and a couple of Islington shops donated toys without knowing it.

From early on in the strike it became obvious that the miners were not going to win on their own, and that the government was trying very hard to avoid any other important section of the working class entering into major activity at the same time. So IAGOU, like others, stepped up their encouragement of workers' activity, they joined a picket for a one-day dock strike, distributed a leaflet by Central London post workers at the Islington sorting office, supported the local nursery workers’ strike against understaffing, made a poster calling for real action on the TUC-called 'Day of Action' ... There was a lot of talk around of the need to open up-a ‘2nd Front’ against the state, yet IAGOU managed to avoid the obvious conclusion of what they themselves were saying - that they should have been stepping up their struggle as part of the unwaged movement. IAGOU were fairly weak at this time, which to some extent explains why they looked elsewhere for the '2nd Front', but they were weak because they were constantly looking elsewhere. Once the racist checks were postponed they had little contact with the dole and DHSS offices, but instead waited for the masses to be attracted to the Centre by their extremist political proclamations. The reason for IAGOU’s existence, that the unwaged must organise and fight their own battles as part of the wider working-class movement was effectively forgotten, and they relegated themselves to the position that the left had tried hard to impose on them and that they had always resisted, the position of individual supporters of the struggles of the waged and of a particular political line. Of course the unwaged movement must support the struggles of other sectors of the working class, and the miners’ strike was a very important struggle, but the development of unity depends on each struggle becoming a catalyst for the others. The threat by the DHSS to reduce strikers’ miserable benefits by the amount of any donations should have been fought at the Islington DHSS offices, along with more general threats against benefits. The state's attempts to make energy production more profitable should have been fought from the other end, through struggle for concessionary rates for (or free) fuel. Discussion should have been started among the unwaged on what the strike could mean for them. Despite having miners using the Centre, they were never asked to speak at a meeting there. The one aspect of the strike that IAGOU did take up and try to encourage to other sectors, was the necessity of using all possible means and force to fight our struggles.

Generally IAGOU made great efforts to support, and encourage support for other struggles, such as the Newham 8 (8 Asian youths arrested and charged for defending their community against racist attacks) the nursery workers' strike, the struggles at Kingston and Southwark unemployed centres against their managements. But IAGOU seemed to have great difficulty in keeping permanent contact with other groups, partly through the turnover in active members, partly through the constant rise and fall of other groups and partly through quarrelling.

In the beginning relations with Islington Trades Council were fairly good especially with the labour left. The Trades Council was dominated by the Communist Party, not because they were in a majority, but because they were the ones willing to take responsible positions and do the work, and because they had contacts (and party links) with the regional TUC and other Trades Councils. On the question of the Unwaged Centre (as on all other questions) they followed the TUC line - that centres should be run by paid workers and controlled by a management committee dominated by the council and unions. But the labour left were more supportive of IAGOU and used this, and other issues to depose the CP and take the leading positions. This was the time of the council's defection to the SDP, and when Labour won the new elections, these new Trades Council leaders had become councillors, leaving the CP back in control. Despite the differences, the chair of the Trades Council did a lot of work to get the centre and became a trustee of the building, but in April '83 he resigned this position and tried to stop the council funding because of his (and other ‘responsible authorities’) lack of control over day-to-day running. He claimed that as the money was controlled only by the users themselves, they would 'take the money and run'. This left relations rather bad. The Trades Council still had two delegates on the Centre's admin committee (with 4 from IAGOU) but for a long time meetings were very irregular, and a formality when they did happen. And IAGOU had two fraternal delegates (meaning they could only speak when spoken to) on the Trades Council, but they only attended to make sure they weren't being attacked, and to enjoy the outbursts of the secretary, who would explode at the mere mention of IAGOU. This situation suited the newcomers to IAGOU, not only because it left them free from any interference, but also because of their view of unions as bureaucratic organisations, controlling workers’ struggles and dividing them. Of course at local level most union delegates and officials are still workers, often radical workers critical of the leadership and bureaucracy, but as long as they see the union as the organ for struggle, and seek merely to reform it, they strengthen it, and so those manipulators and parasites most fit to run it, and sabotage the power of the working class, to spread its struggles across all imposed boundaries and fragmentation, and to directly seize power and the wealth we produce. Unions exist to mediate between us and our enemy (assuming and imposing their right to exist) and between us and other groups of workers. Those who run unions can never share the direct interests of their members, and do not even have to pretend to have common interests with those not in the union, who must therefore be kept separate.

IAGOU always saw themselves as an active minority, not as representatives of anyone, but to some extent this is also the true position of local union delegates. They are often elected to positions of 'representation' because they are active and willing to do the work - because they are an active minority. But as they take up positions in the hierarchy (on the grounds that it is better for them to be there than someone worse - the excuse of all reformists) they get caught up in the machinery of representing ‘their’ members (so requiring majority support before doing anything, no matter how important they consider it) representing the union's decisions and-actions to the members, mediating with the boss, more and more meetings…… To break with the union structure means not only to lose the restrictions imposed by it, but also the support for (some) struggles that comes from official recognition. The fact that support is dependant on going through the 'correct channels' shows how different this is from solidarity - in fact through ‘replacing’ solidarity, it represses it - although rank and file activists are constantly battling to create something meaningful out of the empty form of words and gestures behind which each union continues to carve out its own kingdom of separate interests.

Anyway, when IAGOU were forced to turn to the Trades Council for support against the threats of the council and the GLC, they found they actually had quite a lot in common with some of the delegates. Relations with activists from the DHSS staff were particularly good - IAGOU often joined their pickets and took up their campaigns, while they kept IAGOU informed of goings-on at their offices and were the most active in the struggle to keep the Centre open. There were also good relations with delegates from the 'voluntary sector' (council funded groups, advice workers etc) who were often involved in similar struggles with the council. While the Centre was finally being evicted, a housing advice agency was being victimised and then closed down because of its campaigning, and publicising of racism in the council's housing allocation. IAGOU also started getting involved in some of the Trades Council run campaigns, such as the campaign against the privatisation of the health service, which was effectively sabotaged by the health workers’ union rep (a member of management!) who complained about the campaign being run by non-health workers, while ensuring that ‘his’ members could not get involved. Again IAGOU became one of the main issues dividing the CP leadership from the left majority, and eventually the chair and treasurer resigned and the secretary was voted out.

7) THE END OF THE CENTRE

It was in May '84 that the first suggestion was made by the GLC that the funding would be cut off. At this point the only reason given was that IAGOU was not considered a priority, but when other groups started writing letters of support, a list of reasons came back - 'the irregular hours that the Unwaged Centre opened' which had been sorted out 8 months earlier, 'the smallness and relative unrepresentativeness of the group running the Centre, whereas they now wanted centres run by a couple of paid workers, and control over spending (in particular money given to Wageless Women so that they could control their own struggles). IAGOU answered these points and started trying to improve the Centre, by redecorating (now that the building works weren't going to happen) more publicity and trying to get input from other local groups. Groups were invited to meetings to discuss the direction and running of the Centre, but none turned up (not even the Latin American groups which used the Centre for film shows and meetings) - when they were invited to regularly use the Centre (so freeing IAGOU from having to be there all the time) only the Claimants Union showed any interest, and eventually set up a new branch there, which only created confusion in the Centre. The local GLC councillor was invited round so that IAGOU could put their case to him, but instead he was only interested in putting the GLC case to them, showing who he really represented.

Then in September the Centre became front-page news in the local rightwing rag (and even got a mention in the London Evening Standard) when they noticed one word in the window display, and blew it up out of all proportion. Apart from the many inaccuracies (the most obvious being that about £40,000 was received, not £60,000, the group's accounts were already in the hands of the council, although a bit behind, and the "poster saying Suspend the Bosses"' were actually stickers saying 'Support the Bosses') most of the group were pleased at the publicity, and thought unwaged people would be attracted by this image. But apart from a few people popping in to say 'if the Gazette is against you, you must be OK', this didn't seem to work. The identity of the man 'who visited the centre regularly' but claimed that 'people like me can not go in there' was never proved, but he was believed to be a member of the Socialist Party of Great Britain who was upset at being refused access to the duplicators for his party propaganda, and who was later seen at the Gazette office. There were some fears for the safety of the Centre, as a Gazette front-page attack on the Community Press a couple of years earlier had been closely followed by a fascist fire-bomb attack, but for some reason the Centre was left alone.

After this the council and GLC made it clear that they were really objecting to the group's campaigning;

'You have a radical libertarian approach to the problems of society... the activities you wish to carry on are sometimes incompatible with receiving public money' (GLC)

I am concerned that the philosophy of IAGOU is that of a political campaigning organisation rather than a provider of services (Islington)

Of course IAGOU were not against services for the unwaged. They gave advice and support, cheap tea and coffee and-sometimes meals, somewhere to meet, films etc, but all this was seen as part of organising, not as servicing. The council wanted to be able to say ‘look what we're doing for the unwaged’, IAGOU said 'come and see what we can do for ourselves'. Between April and August '84 a record was kept of visitors to the Centre - it varied from 3 to 20 a day (more for some films) which compared reasonably with other centres, and it would have been hard to fit many more people in, but the council were not impressed, or even interested. They decided to organise trips to other centres to see how they worked, first to the Reading Unemployed Centre. Any comparison with Islington was impossible; it had 24 paid workers, a lot of room and money and no facilities for campaigning - the delegate from the Chamber of Commerce was most impressed. Then to Southwark, where the centre was at that time being occupied by the users. There had been a long-running battle by most of the users and workers against the bureaucracy, manipulation, racism and sexism of the management committee, and when, in October ‘84, a black woman worker was harassed and assaulted by members of the management committee, they took over the building. But as far as Islington Council were concerned Southwark was a good example of how an unwaged centre should be run, and their report did not mention the occupation. The final visit was to Greenwich, which had a good centre but at that time no active unwaged group, partly because some of the leading activists had become workers there.

IAGOU had to admit that the other centres supplied a better service, but because they were given the money to do so. For example they were probably the only centre around without their own minibus, making them dependant either on Southwark for lifts (to mining areas, to support the Camel Laird occupation, to lobby the TUC, to demos etc) or on the council social services, who would not allow their minibuses for 'political' use(their office was only two doors away, so when a minibus was requested 'for a trip to Kew Gardens', they could see an advert in the window for a trip to a demo in Newham) and they were only allowed to specially qualified drivers, which IAGOU didn't have after March '84.

The council then started talking about setting up a new centre, which IAGOU certainly didn't mind - apart from the original problems with the building, the heating system had exploded with a torrent of boiling water, the damp was eating away the floor and wall at the back and the head landlords, having refused permission for alterations, were now demanding restoration work that had been included in the plans – but the important point was how the new centre was to be run.

In May '85 IAGOU drew up a new proposed constitution, including paid workers, greater concentration on services and wider representation on the admin committee. The council ignored it and told IAGOU to disband, and in July gave them 3 months notice to move out. Then in October they invited IAGOU, the chair of the Trades Council and Starting Point (an unwaged youth project in south Islington) to a meeting to discuss the new centre. At this meeting they brought out their proposed constitution (which most people had not seen before), shrugged off all criticism with ‘it can be changed later’, and effectively told those present that they were the management committee for the new centre. All the non-council members resigned these positions as soon as they returned to their groups to discuss it. The meeting also organised a trip to see possible sites for the centre, except that the council didn't organise their part, so that out of three proposed sites, only one was found, and even with this one nobody knew which part of the building was available, but it was totally inappropriate anyway. The council put their proposals, not agreed by anyone else, to the GLC and got £30,000 from them for the 5 months to the end of the financial year. £30,000 for a non-existent centre, and IAGOU were accused of wanting to ‘take the money and run’. The Trades Council tried to get the constitution reopened for discussion, and the Centre kept open until the new one actually existed, but they only managed to get a statement that IAGOU might be allowed to stay until 31st December. The new centre of course never came about.

But IAGOU weren't going to disappear without a fight. On October 15th they held a demo outside the council meeting at the Town Hall. Only about 30 people turned up, plus 20 council workers who were demonstrating about something else but had forgotten their leaflets. Only one person from the other London unwaged groups turned up, and none from the Trades Council.

The best bit was that some housing association had supplied free food for the council as a bribe, and demonstrators wandered in to partake, as did some local kids attracted by the chant of 'Islington cares, food upstairs'. There was some heckling during the meeting, but a group of the activists managed to get locked out while trying to get permission to speak.

- [Cartoon caption - bailiff saying to copper; "Don't worry officer, they'll be out soon - they have to sign on tomorrow..." (Islington Gazette, 25/10/85)]

On the evening of October 18th IAGOU started their illegal occupation of the Centre with an all-night party, and from then on the place was occupied 24 hours a day, with a rota for nights. Posters from the original attempt to occupy the place were rediscovered and stuck up everywhere. A benefit gig was held at a squatted centre in Wood Green, which made some money, mainly on the drinks. The occupation raised people's enthusiasm for a while as publicity was organised and new campaigns planned. An ‘unwaged Xmas Presence’ was planned to attack the misery of the festivities, but as the time got nearer people lost interest. It became obvious that it would not be practical to try anything more than a symbolic defence of the centre and by the end of the year the important issues became where the equipment and meetings could be moved to, and selling off the equipment that couldn't be taken with. The idea of occupying the Town Hall or some other Council building when the eviction took place was discussed, but people were getting bored with occupying. The phones were cut off (with about £2,000 owed), the equipment packed up, and the occupation fizzled out. The Centre was finally evicted in February ‘86. After 20 months the building is still empty.

Meetings continued at an office in Essex Road, but most of the members had lost interest, including some of those who still came. Great efforts were made to attract new people and remain public - the GLC farewell festival was leafleted, a public meeting organised on the chaos at the DHSS (which nobody came to) and a demonstration was called on the night of the council election against whoever won, but the turnout was pathetic and everyone went straight to the pub.

They moved again, to a new squatted centre in Upper Street, but despite a lot of publicity nobody new came, and by the summer of ‘86 IAGOU had gone to sleep.

==========

Comments

The reference to what a

The reference to what a supposed member of the SPGB is alleged to have done seems implausible. Why would the SPGB need to use the Action Group's duplicator when it already had one on its own premises? Besides, the author himself says that it's just an unsubstantiated speculation. Sounds more like prejudice.

"Molly's" was actually called

"Molly's" was actually called Molly Tov's but shortened to Molly's. It was named by me; mainly run by anarcho-feminists, we set up a veg cafe producing low cost meals supplemented by the food we located at the end of Spitalfields each early morning that the sellers has left over. It was previously a kebab shop and many times people came in asking for a kebab! I lived there with three other guys. We had an anarcho-feminist symbol painted on window and a squatters logo on the other, a lovely sight. I'm not sure what the cafe has since been turned into in the uber capitalist Islington. Those were great days, full of expectation and life.

Hi, I lived at Molly's for a

Hi,

I lived at Molly's for a while with my then girlfriend/partner, helped run the cafe and centre and set up the claimants union and was friends with IAGOU. Wondering who you maybe?

I lived at 53 Cross St in one

I lived at 53 Cross St in one of the Black Sheep Housing Coop houses.

I remember breaking in to squat the building, which we'd been checking out for a while. We freaked out when we went upstairs as it looked like someone was living there...unmade bed, clothes scattered around. Once we calmed down we realised that it was just that someone had left in a hurry. We had a jumble sale with the clothes.

Although I was working full time as a computer operator I did shift work so still managed to work in the cafe, go to the vege market etc.

Fun times, but eventually I got tired of slaving away to cook cheap food for Islington trendies.

Jenny