Partial online archive of Insurgent Notes, a journal founded in 2010 and edited by Loren Goldner and John Garvey.

Communism is for us not a state of affairs which is to be established, an ideal to which reality [will] have to adjust itself. We call communism the real movement which abolishes the present state of things. The conditions of this movement result from the premises now in existence.

Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels, Communist Manifesto

Editors: J. Garvey, L. Goldner

Associates: A. Barksdale, D. Berchenko, L. Carter, J. Locks, C. Price, R. Scypion, A. Zahedi

Insurgent Notes is a collective-based journal that will publish online several times a year.

Content from the debut issue of the journal.

Full contents at http://insurgentnotes.com/past-issues/issue-1/

Comments

Introduction from the first issue.

Communism is for us not a state of affairs which is to be established, an ideal to which reality [will] have to adjust itself. We call communism the real movement which abolishes the present state of things. The conditions of this movement result from the premises now in existence.)

Marx/Engels, The German Ideology

We take our Marx and Engels seriously. Recent history, beginning perhaps (in the US) with the UPS strike of 1997 and the “battle of Seattle” in 1999, now quickened by the abject financial and ideological meltdown (Fall 2008) of the three decades of the stifling “neo-liberal” era, has favored a certain revival of the radical critique of capitalism, by which we understand first and foremost the work of Karl Marx. Conferences of rock concert dimensions, attracting thousands of young people in Europe, the US and East Asia, gatherings that only a few years ago would have featured some (now happily passé) hip literary theorist, are today devoted to the work of Marx . The premature rumors of Marx’s demise–almost a cyclical indicator in their own right–have recurred often enough in the past 120 years, but Marx’s books, in the wake of the fall 2008 world financial meltdown, were cleaned out of the bookstores of the U.K. and Germany.

“Theory must seek its practice,” Marx wrote long ago, but “practice must also seek its theory”, and such theoretical ferment expresses the rising tide, in fits and starts reaching back to the 1990’s, of an accelerating global reaction to the ravages of the “neo-liberal”, “Washington consensus” phase of capitalism, after the rollback of what we might consider he last (l968-1977) offensive of the world working class.

We, less than a dozen intellectuals and militants, limited for now to the U.S. but with networks of association reaching into Europe and Asia, are launching Insurgent Notes as a contribution to this ferment.

Our minimal program of agreement is:

- commitment to social revolution for the abolition of the wage-labor system, i.e. the capitalist mode of production, and an orientation to the wage-labor proletariat (i.e.the working class) and its potential allies as the main force for such an abolition;

- an affirmation of the great experiences in direct democratic management of production and society (soviets, workers’ councils) that came to the fore in the failed revolutions of the 20th century (Russia, Germany, Spain, Hungary) or, closer to U.S. experience, the self-managed Seattle general strike of 1919 as important antecedents, but hardly the last word, in our project;

- a commitment to “activity as all-sided in its production as in its consumption” (Marx, Grundrisse), and the “development of human powers as its own end” (Pre-Capitalist Economic Formations) within the expanded reproduction of humanity as the true content of communism ;

- a deep-seated skepticism about vanguardist notions of revolution; while we at the same time affirm the need for some of kind of organization that emerges practically and concretely from real social struggle–not “sprung full-blown from the head of some world reformer” (Communist Manifesto)–and which conceives of itself not as “seizing power” but as a future tendency or current in a future self-managed society;

- a rejection of nationalism of any kind as an obstacle to such a revolution;

- a rejection of existing Socialist, Communist or Labour (let alone Democratic) parties in the advanced capitalist sector as alien to our project, and as parties whose (well-proven) role is nothing but the management of capitalism in one or another form, as well as rejection of the “extreme left” groupings (Trotskyists, Maoists) who see such parties as “reformist” “workers’ parties”;

- a rejection of the few remaining “real existing socialist states” (Cuba,Vietnam, China, etc.) and their Stalinist predecessors (the defunct Soviet bloc) as any kind of model, degenerated or not, for the kind of society we wish to help build;

- a rejection of the renascent “anti-imperialism” of recent years, associated with the loose alliance of Chavez and his Latin American allies, China, Hezbollah, Hamas, Amadinejad’s Iran, etc., as an anti-working class ideology serving emergent elites in different parts of the developing world;

- a rejection of any strategy of “capturing the unions” for such a project, as practiced since the 1970s by various “boring from within” Trotskyists, etc.;

- a rejection of post-modern “identity politics” as the ideological articulation of the very real problems of race, gender, and alternative sexuality, but which must be relocated in class politics.

These basic points do not particularly distinguish us from a number of existing currents, broadly associated (in the US and Europe) with the “libertarian communist” or “left communist” scenes. We do not feel the need, at this early point in our activity, to noisily affirm any distinguishing trademark, except to say that we are launching Insurgent Notes because we have found no place for ourselves in any existing grouping. We look forward to comradely dialogue with such groups and individuals who may feel some attachment to them and also look forward to larger regroupments forged in the kind of practical struggles that can cut the knot of theoretical and practical disagreement. We well remember Marx and Engels, in their London exile in the early 1850s, turning their backs on the petty wars of the sects in the ebb that followed the 1848 revolutions. While we do not see the contemporary period as one of ebb, but rather as one of a rising curve of struggle, our perspective for now is nonetheless Dante’s “segui il tuo corso elascia dir le genti” (go your own way, and let people talk).

The past 35-40 years since the 1968-1977 working-class offensive, however difficult and trying for would-be revolutionary Marxists, have hardly been without practical import for our perspectives. The collapse and disappearance of the Soviet Union and its bloc, and the devolution toward full-blown integration into the capitalist world market by China (and, more recently,Vietnam) have largely cleared away the “Russian question” over which so much polemical ink was (perhaps necessarily) spilled over so many decades. It is clearer today than it was 40 years ago that the Soviet “model,” once its brief internationalist and worker-based phase up to 1921 hardened into Stalinism and then was, as such, exported to rule one-third of the world’s population by the mid-1950s, was about the eradication of pre-capitalist social relations in agriculture, and about the “reinvention of the wheel” of primitive accumulation and the extensive phase of capital accumulation the West had experienced in the 19th century. Its nationalized property, state planning and state monopoly of foreign trade—those features which even today various Trotskyists call features of a “workers’ state”—were developed by closed mercantilist states from Renaissance Italy via 17th century Prussia to Meiji Japan. Well into the 1970s, such states were conceived by most theories on the left as being something “after” private capitalism, whereas in 2010 it is clear as day that they precede a more privatized capitalism. As their own ideologues unwittingly said, they “lay the foundations of socialism,” which is exactly the historical task—developmentof the productive forces—of capitalism. We know today, far better than 40 years ago, that “developing the productive forces” is not the task of socialism or communism. We know that the centralist and statist dimensions of Jacobinism and Bolshevism, not to mention Stalinism and Maoism, arising as they did in overwhelmingly agrarian societies, express the weakness and not the strength of the revolutions that carried them to power.

The legacy of Bolshevism in particular (which we neither embrace nor despise) has among other things greatly obscured the fundamental problem identified by Marx as the alienation of universal from cooperative labor. This problematic has been reified for over a century by variations around the themes of a (mainly intellectual) vanguard “leading” the working class and a libertarian counter-point glorifying workers as the point of production to the exclusion of all else. The much deeper reality of the problem is built into the nature of capitalist society itself, based as it is on the separation of mental and manual labor. Universal labor is science, art, and intellectual work, understood in the broadest sense, which will one day be fused, with aspects of contemporary “hands-on” material labor, into the “all-sided activity” which Marx in the Grundrisse identified as the overcoming of the antagonism of work and leisure by the abolition of commodity production. Capitalism in the past 50 years has increasingly required universal labor quite as much as cooperative labor, first in scientific research in its “ceaseless striving” to develop the productive forces and, in parallel, has enlisted artists and intellectuals to perform its increasingly threadbare ideological unification. Since most of us are, in this embryonic stage of our activity, intellectuals, we align ourselves with the tradition of Marx, as that small minority of intellectuals who refuse their assigned role in the production of ideology and turn their theoretical weapons against the wage-labor system.1 The unification of universal and cooperative labor is another way to express what we mean by “all-sided activity” (again, the Grundrisse).

We do not wish to start our existence by picking up the 1960s/1970s debates about “forms of organization”: party, soviet, workers’ council, union. All such questions are important but they are subordinate to the larger question of content. Content in this case means a program for radical social reconstruction once the world is dominated by “soviet-type” power. But in our view such a revolution will not take place if there is not prepared in advance a substantial stratum of workers with a clear programmatic idea of what we wish to do with the world when we take it away from the capitalist class. That is the true “vanguard of the working class,” not some self-appointed vanguard party intent on “seizing power.” Such an advanced stratum of workers and their allies may very well at some point form a political party, or even several, but our perspective must always be as a current in the future multi-tendency “world soviet.”

Too often in the past, in Russia (1917), Germany (1918) or Spain (1936), workers have established something resembling soviet power as we mean it (in the latter two cases really only as dual power) rooted in workers’ councils, but since such formations were lacking precisely that “programmatic imagination”—what to do next–they quickly handed real control over to the specialists of power in the state or were in short order dispersed and savagely repressed. In our view, the question of revolution is not first of all about forms of organization, but about the social-reproductive programmatic content required to abolish wage labor, commodity production, the capitalist law of value and thereby class society. And that means, for example, having clear ideas of what to do about the environment, energy, the work day, the organization of human living space, education, health care and many other issues that all but dominate the world.

These issues demand attention far beyond the individual workplace. We make this point because many of our political ancestors cut their proverbial teeth in the defense of the practical and political wisdom of workers on the job. We retain a great deal of appreciation for that perspective. But capital has moved on and the point of production is no longer quite what it once was. Profoundly radical actions and demands from the past are no longer sufficient. More jobs and workplaces in the advanced capitalist world will be abolished by the transformation than will be placed under “workers’ control.” We need to define what we want far beyond the limits imposed by what we are faced with.

Let’s take a recent example. The Argentine piqueteros developed in the late 1990s as a resistanceto the drastic attack on workers there through neo-liberal “reform.” As hundreds of factories closed and workers were thrown into unemployment and in some cases ultimately into lumpenization, the piqueteros abandoned the old factory-based strategies of the left and took the struggle to the supermarket, the hospital and the freeway blockage. They fought back against repression by attacking police stations and publicly outing the torturers of the 1976-1983 “dirty war.” In December 2001, the Argentine neo-liberal “miracle,” based on impoverishment of the once-militant working class, collapsed and the state with it. Even the middle classes were fed up with the Peronist state. The piqueteros, mainly recruited from the youth of the downsized and casualized working class, took over the center of Buenos Aires, and power lay in the streets. But no force was prepared to take the crucial next step and reorganize production on a working-class basis, and to thereby nullify the frantic efforts to cobble together a new bourgeois government. The moment was lost; thePeronists regrouped, and the piqueteros were swept aside or even co-opted into the new Peronist patronage machine.

Insurgent Notes might perhaps be distinguished by our emphasis on what Marx in vol. II of Capital called expanded social reproduction. In our future discussions of what a victorious revolution must do about the many social and biosphere problems mentioned above, above all those located outside the “immediate process of production,” we hope to begin a generalized discussion, but one which, in contrast to a sect, we hardly claim to “own.”

In contemporary “advanced capitalism” (advanced mainly in decay—as assessed by the increasing disparity between what could be and what is) an enormous number of people, the great majority of them wage-laborers (including wage-labor professionals) consume surplus-value and do not produce it. Some of what such workers do is all but essential to a human society–they educate the young, care for the sick, and attend to the elderly. However, much else that such individuals do is simply and straightforwardly a waste of their and our time on this earth. A primary focus of Insurgent Notes, in our attempt to spark a discussion of expanded social reproduction, will be the potential of how the expenditure of so much socially-unnecessary labor power, redirected to socially-useful activity and to facilitating “the radical shortening of the working day” which is the sine qua non of the full human self-development for which we fight. And such a redirection requires, it goes without saying, the abolition of the capitalist mode of production.

Insurgent Notes addresses itself initially to those sympathetic to our assessment of the overall situation and notions of what to do about it. We recognize that, for the moment, this in all likelihood means those intellectuals like ourselves and possibly some working people with a certain political and theoretical formation, or those looking for itand not finding it in the broader (self-styled) anti-capitalist milieu. We seek collaborators, initially, among those who share our interest in making the critique of political economy, the focus on social reproduction, and a program for social reconstruction central to our activity and initial intervention. We do not intend to build a network of unformed activists around ourselves as a general staff but rather, to the extent possible, within current conditions, a network fusing “universal labor” (critical intellectual work) with “cooperative labor” (practical intervention). That will mean, initially, the work of writing, editing and publicizing this journal. We intend to organize internal and external study groups on Marxian theory and revolutionary history. As our capacity to do so grows, we intend to establish ongoing investigative work on the global political economy, in order to arrive at ever-clearer understanding of what a revolutionary program and global reconstruction can mean. When we have the numbers and resources to do so, we intend to move to more popular and accessible forms of expression.

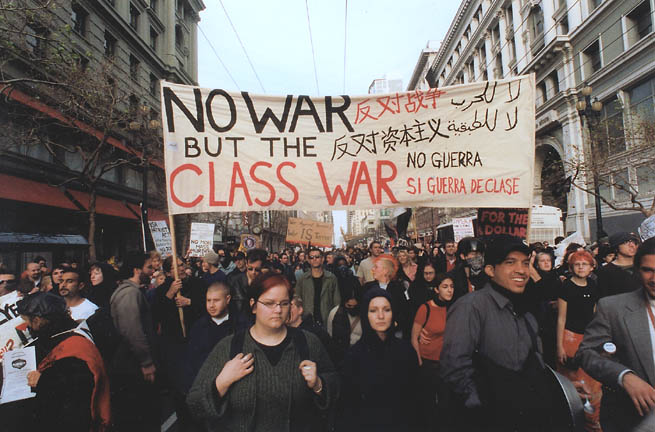

We intend to follow and, where possible, participate in ongoing struggles, large and small (an immediate example today would be in Greece), developing strategic and tactical, understanding of the necessities and possibilities of the present. We wish to reconnect with and update the Marxian tradition of strategy as developed by such figures as Engels and Trotsky, but also (more broadly) of the Clausewitzes, Makhnos, Villas, Durrutis and Sun Tzus of world history. We want to study and make accessible an understanding of the strategic and tactical strengths and weaknesses of such moments as the Argentine piqueteros (or the remarkable earlier Argentine cordobazo of 1969), the Chilean cordones comunales of 1973, the Bolivian revolt of 2003, the Oaxaca uprising of 2006, or the Kwangju uprising in South Korea in 1980. Closer to home and to our present, we would include the Seattles and Genoas of the past decade .

We wish to make this kind of knowledge available to the “real movement,” and not as the “property” of ourselves as a sect. Our organizational loyalty is precisely to that “real movement,” not to any artificial, abstract and separate self-definition apart from it. We believe that the more theoretically and practically armed the real movement is, the less it will need “leaders” and “vanguards” of any kind. In contrast to the centrality of key leaders (one thinks e.g., of Lenin) in most revolutions of the past, we feel that the deeper and more substantial the revolutionary leadership is, the stronger it will be, and the broader the base of the movement, the less violent its victory will have to be.

Cultural activities and the arts are not our strong suit, but we recognize their importance for our broader project. Consider the centrality of song for the IWW. Consider the dozens of songs created on the spot during the Oaxaca uprising. Consider the broad activities in song, dance, and movement art work of the Korean minjung movement of the 1970s, taken over into the broader Korean workers’ movement to this day. We know there is a long and noble tradition of artistic involvement in revolutionary movements reaching back more than 200 years, and since the early 20th century, avant-garde attempts of various quality to build a bridge between the arts and life. The great majority of those early 20th century efforts (German Expressionism and the Bauhaus, Russian Futurism, the artists produced by the Mexican Revolution), Dada, or surrealism) after the defeats of the 1917-1921 insurrectionary wave, were simply re-appropriated by the bourgeois cultural museum and presented under glass as “art,” stripped of their broader radical intent. After World War II, groups such as the Situationists attempted to use the method of “diversion”(detournement), first developed in poetry from Lautreamont onward, in broader subversion, but after having a certain impact on the May 1968 general strike in France, “Situationism” in turn was made respectable almost to the point of the creation of “Situationist Studies” and “Situationism scholars” in universities. These currents all represented attempts to use methods first developed in the arts to the communication of radical ideas. We recall the Polish workers of Poznan who, in 1956, briefly captured the state radio network to present their own perspectives or, again, in Oaxaca where the movement captured and controlled radio and TVstations for weeks.

Something takes place in revolutionary moments that have been studied and captured in writing—to the extent that it can be captured in retrospect at all–only rarely, where the Marxian concept of the “class-for-itself” steps out of textbook exegesis and “seizes the masses,” something akin to amaterialist version of Hegel’s idea that “the truth is a Bacchanalian revel in which no member is not drunk.” Or again to paraphrase Hegel’s notion that the “real is rational” when the real is understood as exactly such moments, those which occur when the “inverted world” of the everyday is turned upside down, when the isolated individual realizes his/her true reality in a collective surge that few, if any, suspect could slumber under such passive appearances. One suspects that something of this kind took place in Barcelona in July 1936 when the unarmed crowds charged the military and police and won the day or in Budapest in November 1956 when the country was placed under a national system of workers’ councils in a few days. In such moments, we suspect, Marxian theory, strategy, and aesthetic expression all fuse into some ephemeral collective sense of being capable of everything, whatever the odds.

We should not exaggerate their importance, because history has shown quite clearly that they were, in fact, not capable of everything. But we of Insurgent Notes wish to keep clearly in mind that such qualitative moments in history are a fundamental part of what we call reality, and we hope to locate all other aspects of our activity in that future maturing in the present.

If these ideas converge with your own, contact us.

- 1“a portion of bourgeois ideologists, who have raised themselves to the level of comprehending theoretically the historical movement as a whole,” Communist Manifesto, London 1979, p. 91.

Comments

Introductory article to the first issue of Insurgent Notes (June 2010).

The Historical Moment That Produced Us

Global Revolution or Recomposition of Capital?

1789 1848 1871 1905 1917 1968 20??

I. Dispersal and Regroupment in Working-Class History in the Capitalist Era

The years 1917-1921 constituted the first worldwide assault on capitalism by the revolutionary working class, centered in Germany and in Russia. That assault was crushed, and the counter-offensive of the following years took the form of, transitionally, fascism, and more enduringly, Social Democratic welfare statism, Stalinism and Third World development states, which succeeded—almost— in burying the memory of its true content and character.

The years 1968–1977 marked the return of revolution, and at least the partial recovery, in a much deepened development of capital’s hegemony, of the communist project left in abeyance by the earlier defeat. The task of Insurgent Notes is to deepen that recovery and to participate in the theoretical and practical regroupment for the next—and hopefully last—global assault.

Looking back from the vantage point of the latest phase of the world crisis that erupted in 2008 (itself merely the latest twist of the “slow crash landing,” sometimes faster, sometimes slower, that began ca. 1970), and from the working-class response to it that, in fits and starts, is taking shape today, one cannot help being struck by the staggering banality of most social, political and cultural life around the world since the late 1970s. By that we hardly mean that “nothing happened”: one need only recall the dismantling of the Social Democratic welfare state, the collapse of the Soviet bloc and reunification of Germany, the rise of East Asia as the most dynamic economic zone in the world, or the emergence of radical Islam. But for those of us who lived through the mass struggles of the 1960s and early 1970s, the three and a half decades of the long slide of the world capitalist system, prior to the meltdown of October 2008, must appear as one of the longest and strangest historical periods since the communist movement first emerged in the 1840s.Those of us too young to have experienced the years of repeated mass movements in the streets, in the heart of advanced capitalism, must make an even greater leap of imagination to grasp the unreality of an era successively characterized by dominant ideology as the “Washington Consensus,” neo-liberalism, globalization, “post-modern” or the “end of history”. From the Paris Commune (1871) to the Russian Revolution of 1905, we might recall a relative ebb of struggle of comparable length, but even then, there was a steady expansion of the organized working-class movement, above all in Europe, both in trade unions and mass-based workers’ parties, on a sufficient scale to even produce, by 1900, the ideological disarray of “revisionism”.

That was then—still the era of the ascendant phase of capitalism on a world scale—and this is now.

By contrast, the period from the mid-1970s onward has been one of almost uninterrupted defeat: brutal dictatorships in the southern cone of Latin America (Chile, Argentina, Uruguay, Brazil); the crushing and cooptation of the Polish worker explosion of 1980–81, containment of the radical currents of the South African workers’ movement in the managed transition from apartheid to austerity, defeat of the workers’ councils of the Iranian Revolution, defeat after defeat of old-style single-industry struggles in the capitalist heartland, from the downsizing of French steel (1979), by way of FIAT in Italy (1980), to the British miners’ strike (1984–85).

The US saw a long string of defeats of traditional union struggles: from PATCO (1981) to Greyhound (1983), Phelps-Dodge Copper (1984) and P-9 (1986) to the Jay, Maine paper strike of 1987–88. By the end of this phase, Wal-Mart had replaced General Motors as the biggest US employer.

Even when workers fought back in forms beyond the traditional, they lost:

- Brazilian workers staged some impressive strikes in the late 1970s but were then channeled into electoral containment by Lula and the Workers’ Party and largely downsized in turn; steel and auto were the most important employers in the late 70s, and Macdonalds and security had replaced them 10 years later.

- Chronically unemployed Algerian youth rioted in 1988 but were co-opted into the Islamic movement and ground up in the subsequent civil war.

- Oil workers and others established workers’ councils during the Iranian revolution (1978–81) whose repression was a major priority of the Islamic Republic that highjacked the overthrow of the shah.

- The South Korean working class exploded in 1987 and made gains into the early 90s, after which it was beaten back by salami tactics and then by the tsunami of the IMF crisis of 1997-98.

- The South African masses forced the dismantling of apartheid, only to be handed over to neo-liberalism by the ANC.

- The Argentine piqueteros’ movement of 2001–2002 brought the government there to its knees, but did no more, and was dispersed and co-opted by the recycling of Peronism.

Add to this picture the succession of local war upon war, from Lebanon (1975–1990) to the 40-odd wars in progress in the early 1990s, culminating (to date) in the 1994-1998 African near continent-wide war (4 million dead), the U.S. debacle in Iraq and potential new debacles in Afghanistan and perhaps Pakistan. The proliferation of murderous nationalisms in ex-Yugoslavia and on the periphery of the ex-Soviet Union made the proletarian internationalism that forced the end of World War I seem very remote indeed.

II. The Global Wage-Labor Work Force as the Sole Practical Universal

As we emerge, hopefully, from this dismal period of rollback, we recall Rosa Luxemburg’s remark, shortly before her murder in 1919: “The revolution says: I was, I am, I shall be!” We assert the ongoing reality of communism, “the real movement developing before our eyes,” as Marx put it in the Manifesto. Like Hegel’s “knights of history,” we locate our identities not in any immediacy but in the emerging new universal that must be the cutting edge of the next global offensive.

What does this “universal” mean? As a first approximation, it means the global program which can unify, as a “class-for-itself”—a class prepared to take over the world and reorganize it in a completely new way—the wage-labor forces currently dispersed in the (somewhat diminished but still central) classic “blue collar” proletariat, the dispersed and casualized sub-proletariat, and those elements of the technical, scientific, intellectual and cultural strata susceptible to allying with such forces. These are, in “inverted” form, the forces actually comprising what Marx called the “total worker” (Gesamtarbeiter). Scattered around the world as it is, above all by the past four decades of debt-driven social retrogression, this “total worker” may seem to be a chimera, but it nonetheless, under the scattered appearances—the very fragments theorized and glorified by “identity politics— of capital accumulation, it does the world’s “use-value” work every day. Subordinated as these forces currently are to the increasingly insane drive of the accumulation of CAPITAL careening toward barbarism and planetary destruction, the programmatic reunification we advocate may seem “utopian,” but it is in fact the survival of this outmoded social system in any remotely humane form which is the real utopia of our time.

It is to the programmatic and practical unification of these forces that we of Insurgent Notes are committed.

III. Working-Class Dispersal and Regroupment as an Historically Ascendant Spiral

As the admittedly dense language in the preceding may be opaque to some, a bit of “unpacking” is in order.

The last concerted proletarian offensive of 1968–1977 might be characterized, on a world scale, as a revolt against the factory assembly line. Although, as indicated, this movement failed to articulate and implement an “alternative social project,” the goals seemed, to some, relatively clear. Reconnecting with the workers’ councils and other forms of mass assembly of the previous great revolutions (Russia 1917, Germany 1918, Spain 1936, Hungary 1956) or less total mass strike phenomena (such as Portugal in 1974–75 or the black-led wildcat movement in Europe and the U.S. from the 1950s to 1973), the goals of the movement were understood to be taking over the existing industrial plant and placing it under “workers’ control.” Given the already skewed character of capitalist “growth” after 1945—we need only think of the net negative social impact of the automobile—such a perspective was already flawed, but it at least had the merit both of seeming palpable to many workers and of providing a focus for the most advanced struggles of that time: the generalized wildcat movement in Europe and North America.

“All power to the international workers’ councils” was the seemingly best “universal” of that era, and there were ephemeral moments when its realization did not seem that far off.

The capitalist counter-offensive involved a direct attack on the “visible” dimension of the movement toward “generalized self-management”: breaking up the big factory into cottage industry and isolated rural “greenfield” sites, further de-urbanizing workers into sprawl and exurbia, the casualization of labor, outsourcing to the Third World, and “high tech” intensification of production. The resulting “de-socialization” of the workers of the 1968–1977 rebellion achieved in these ways was deep and thorough. It was a textbook illustration of the way in which technology—in this case, first of all, new telecommunications and improved transportation—is inseparable from its capitalist uses; not since the mass production of the automobile did an innovation have such an initial impact of isolating and dispersing the universal class which the proletariat IS. That such telecommunications and transportation may tomorrow contribute to the practical unification we advocate is another matter, and remains to be seen.

Our guarded optimism is only strengthened by the long view. Strange as the preceding decades may have been, cycles of defeat and renewal of the movement to abolish bourgeois capitalist society are nothing new. The workers’ movement has repeatedly had to regroup and learn from defeat, and to respond to new forms of capitalist containment. From the Enragés and the Babouvist Conspiracy of Equals of the French Revolution until 1848, the very early movement had to slough off conspiratorial putschism (Blanqui) and various utopian schemes (Owen, Fourier) to emerge in the first concrete, armed expression of communism in the Paris June Days of 1848 and their extensions in other parts of Europe. Out of that 1840s upsurge came the mature self-consciousness of the movement in the work and practical activity of Marx and Engels. The long boom following the defeat of 1848 brought on the 1860s rise of struggles, from U.S. slave emancipation to the European strike wave that produced the multi-tendency First International and culminated in the Paris Commune.

The crushing of the Commune and dispersal of the First International marked the shift of the cutting edge of capitalist development and the maturing workers’ movement to Germany, the long illusion of Social Democratic reformism (trade unions and parliamentary activity), as well as the bowdlerization of Marx’s theory of the real movement into an ideology for the industrial development of backward countries, first in Germany and then, more fatally, in Russia. It inaugurated what might be called the “century of Social Democracy” and Social Democracy’s bastard spinoff, Stalinism (1875-1975), the fatal illusion of statist socialism. Marx and Engels from the earliest opportunity denounced the term “Social Democracy” as an eclectic hodge-podge having nothing to do with communism as they understood it (cf. Critique of the Gotha Program, private correspondence), but the grey eminences of what became the Second International (1889-1914) quietly buried the founders’ critique under the seemingly relentless electoral and trade union advances in western Europe. The illusion that socialism/ communism meant state planning of nationalized property (understood moreover within individual, autarchic nation-states) in fact covered over the reality of a world transition from the formal/extensive to the real/intensive domination of capital (1870s-1940s), a transition perfectly adumbrated in yet another unknown (until 1932) work of Marx, the so-called Unpublished Sixth Chapter of Volume 1 of Capital.

The “real movement that abolishes existing conditions” ripped open the self-contented humdrum world of Social Democracy in the Russian-Polish mass strikes of 1905-1906. As in the Paris Commune with its groping attempt at the abolition in practice of the state (e.g. immediate revocability of delegation), the explosion of 1905 placed on the historical agenda, against the parliamentary gradualism, trade unionism and productivist planism of the Second International, the soviet and the workers’ council as the far more advanced forms of working-class power. And soviets and workers’ councils in turn were at the center of the 1917-1921 world insurrectionary wave, centered in Germany and Russia, that ultimately spread to, and was defeated in, 30 countries. Out of that groundswell from 1905 to 1921 came the next generation of revolutionary theoreticians, including Luxemburg, Bordiga, Gorter and Pannekoek,[1] the self-conscious expressions of the practical discoveries of the working class in motion.

The revolutionary wave of 1917-1921, however, was not deep enough to end the “century of Social Democracy” and productivist top-down planning; quite the contrary, it made the latter more directly palatable to the stabilization of capital. Capitalism recovered its balance, over new mounds of working-class corpses, through previously unknown, or barely adumbrated forms of statism, a decade of depression and a second world war that achieved for the first time (in contrast to the actual reformism of the pre-1914 period) a “recomposition”; this recomposition covered over the reality that in 1914, on a world scale, the global productive forces necessary to abolish commodity production already existed. Part of this recomposition involved intensified accumulation in the semi-colonial and newly independent ex-colonial worlds, as the hegemonic British empire as well as the French empire gave way to American hegemony.

IV. Recomposition and Revolt in the Era of Capitalist Decadence

The long expansion after World War II, under the auspices of various statisms of self-styled progressive veneer, largely seemed to have exorcised the “specter of communism,” particularly since the word as well as the trappings had been taken over by totalitarian states ruling one-third of the world’s population. Workers on the shop floor, however, knew differently, and in both major blocs regrouped and found their way to new forms of struggle, most notably the wildcat strike which from the mid-1950s onward grew in momentum in the US, the UK, France, Spain, and Italy. Polish workers in 1956 forced a shakeup of the Stalinist state and, in Hungary a few months later, without a Leninist vanguard party in sight, proletarians built a national system of workers’ councils in a matter of days and overthrew the regime. In France in 1968, workers staged the longest wildcat general strike in history. This wildcat moment of the workers’ movement after the 1950s had in many places by 1970 wrested de facto control of the shop floor from the capitalists, but it never went beyond that to the practical elaboration of a social project beyond capitalism, and succumbed to the capitalist counter-offensive which began to gather momentum by the mid-1970s. That counter-offensive intensified with the successive triumphs of Thatcher in the UK, Reagan in the US, Mitterand in France, and Teng in China, joined after 1985 by Gorbachev in Russia. Not since the pre-1914 era had ideology spoken so globally with one voice, orchestrating 1) the biggest disparity in wealth since the 1920s, 2) the shredding of most of the social safety nets had been created in the preceding statist era, and 3) using new telecommunications and transportation technologies, a “globalized” dispersion of production that seemed to fragment the previous concentrations of workers which made possible the wildcat era in the West.

All of history since 1914, then, has involved the successive (and to date successful) attempts to stave off the reality of the superannuation of capitalist social relationships, to periodically, through destruction, repression and ideology, to force working people and their struggles back into those relations, whatever the social and human cost.

Since World War I, these capitalist recoveries, in contrast to the 1815–1914 era, have involved recomposition, in the same way that they involve massive destruction of workers and physical plant in a way unknown in the previous century of capital’s dominance. Mere collapse, deflation, depression and “automatic” recovery, as in the decennial crises analyzed by Marx in Capital, no longer sufficed. Recomposition, in contrast to genuine reformism as it was practiced before 1914, means a “reshuffling of the deck,” a lowering of the total social wage bill under the appearances of inclusiveness: trade unions and socialist parties disciplining the working class, worker-management cooperation schemes, or, closer to the present, diversity counselors, NGOs, women CEOs and green capitalism.

What characterizes the new post-1914 period (variously called “decadence,” “the epoch of imperialist decay,” the “real domination of capital”), in contrast to the previous one, is that capital expands, and social reproduction contracts. Recoveries, such as the postwar boom (1945–1970) involved such a recomposition, made possible by the earlier massive destruction, (two world wars, a decade of depression, fascism and Stalinism) the reorganization of the world system (end of the British and French empires, transformation of the world economy—minus the Soviet bloc and China— into a “dollar bloc” under the Marshall Plan, IMF and World Bank, and the imposition of a new “standard of value” based on the new technologies of the 20s and 30s (mainly of consumer durables, e.g. the auto and household appliances) that had been bottled up by the previous, superseded national markets. This recomposition ran out of steam in the mild 1966 recessions (Japan, Germany, US), the 1968 dollar crisis and the final crackup of the Bretton Woods system (1971–73). Not accidentally, that latter period of unraveling saw the sharpest class struggle in decades, before or since.

V. Capital Seeks a New Equilibrium Through Destruction, 1970–present: The Slow Crash Landing

Since that time, capital has been groping for another successful recomposition based on a new “standard of value”,[2] whatever the consequences for social reproduction on a world scale. Those consequences have been destructive enough, and they have hardly run their course.

In these four decades, as indicated, capital expands, social reproduction on a world scale contracts.

Let’s look more closely at the chronology.

1970-73 was the beginning of the “slow crash landing,” announced by the bankruptcy of the Penn Central railroad, a U.S. recession, Nixon’s belated discovery that he was a Keynesian, and his unilateral dissolution of the Bretton Wood system of fixed exchange rates in August 1971. Above all through the pyramiding of debt, capital has mainly kept up the appearances of “normality” in North America, western Europe and East Asia: :”normal” recessions in 73-75, 80-82, 90-91, 2001-2, and the current one beginning in 2007. But looked at from a social reproductive view, the post-1960s history of capitalism has been, on a WORLD scale, little less than a substitute World War III, attempting once again the recomposition achieved in 1914-1945. We merely list the highlights: a 20-30% fall in real living standards in the US, the replacement of the one-paycheck family by the 2-3 paycheck family, whole regions de-industrialized; in western Europe, an average of 8-10% unemployment over most of the period and a general (as yet incomplete) dismantling of the welfare state; in eastern Europe and Russia, wholesale retrogression for workers surrounding enclaves of yuppiedom, built (in Russia) on ground rent from natural resources, not any real production, and in eastern Europe on speculative flows of Western capital into real estate. When we “factor in” Latin America, Africa, the non- oil Middle East, the ex-Soviet Central Asian countries, India and the rest of non-Tiger Asia, we are talking about billions of stunted lives and millions of deaths from disease and general slum existence. Mexico in those decades went from being the “next Korea” (Wall St. Journal, ca. 1990) to the possible next Afghanistan (Financial Times, March 2010).

Only East Asia, now extended to coastal China, stands out as a partial exception, and even there Korea, Thailand and Indonesia underwent the terrible retrogression of the 1997-98 crisis, and China’s post-1978 growth has left about 850 million peasants and its floating unemployed army of 100 million quite out of the boom.

The similarly-touted “India shining” has been exposed by large-scale rural poverty, a suicide epidemic of bankrupted weavers, worker unrest in the industrial suburbs of Delhi, and the resurgence of the Maoist Naxalite guerrilla movement, previously declared all but extinct following large-scale repression in the 1970s.

Asian growth, already a minority phenomenon in the two “emerging giants” China and India,, is more than offset by all the retrogression on a world scale.

But one cannot conceive of a new global assault against capitalism comparable to, and surpassing 1917-1921 or 1968-1977, without a concrete analysis of the changing conditions of the wage-labor proletariat over the past 35 years, conditions as discontinuous with those of assembly-line workers in Detroit or British Leyland or Renault-Billancourt (Paris) in 1968, as the latter were discontinuous with the conditions of German, Russian or Italian workers right after World War I.

VI. Capital’s Assault on Proletarian Concentration

Marx, in the beautiful passages on “Machinery and Modern Industry” in vol. I of Capital, points out that the history of technology can be written in terms of the ceaseless struggle between capital and labor over the length and conditions of the working day, and one must also understand everything capital has done since the late 1970s as a counter-offensive against the worker insurgency of the 60s and 70s. The issue is one of locating a new universal for the unification of the conditions of world wage labor, similar to the practical discovery of the soviet and the workers’ council before and after World War I, and their transient “recovery” in the decade after 1968. The issue is one of locating “immanently,” in today’s world production and reproduction, the “inverted” form pointing to what Marx described in the Grundrisse :

…Capital’s ceaseless striving towards the general form of wealth drives labour beyond the limits of its natural paltriness (Naturbedürfdigkeit) and thus creates the material elements for the development of the rich individuality which is as all-sided in its production as in its consumption, and whose labour also therefore no longer appears as labor, but as the full development of activity itself…[3]

Capital, deeply frightened by the inchoate emergence in 1968-1977 of the search for this “full development of activity itself” responded to the breakdown of the old conditions of accumulation with its second great recompostion of the world working class (following that of 1914-1945), achieved through the breakup and dispersion, on a large scale, of the big factory and its high concentration of workers in dense urban areas in the U.S. and in Europe. It intensified production through new technologies and a revolution in communication and transportation. Capital’s struggle was, as it had always been, to increase productivity while eliminating, as much as possible, living labor from production, but given the high level of productivity already achieved in the 1960s, it was a constant, mystified struggle against the reality that, on a world scale, the living labor necessary to materially reproduce the system had already become “superfluous” as a portion of the total population, and yet urgently necessary, in the dominant social relations, to continue the capitalist expansion of value. We need look no further than the 7 million people in the U.S. prison system (awaiting trial, in prison or on parole, 2% of the 300 million total) to see the warehousing of capital’s surplus population, not to mention the two billion people similarly marginalized in various parts of the Third World.

Technology as such, we understand even more clearly today, following the “high-tech” “new economy” hoopla of the 1980s and 1990s, , is not capital, even if existing technology must of necessity be the material embodiment of capitalist social relationships.

VII. Capital’s Struggle Against the Specter of Its Own Abolition Since the Eruption of the Communist Movement in 1848 and Thereafter

The 1848 emergence of communism as a real movement in the European working class forced capitalist ideology to increasingly mystify, in contrast to all previous class formations, what society could do, namely abolish wage labor, commodity production, capital and, with them, social classes, starting with the wage-labor proletariat. To that end it discarded its own classical political economy, its embrace of Enlightenment rationality, and its advocacy of the rights of the “Third Estate,” since it was now confronted with the proletarian Fourth Estate. It abandoned the Promethean social realism of its artists from Shakespeare via Goya to Balzac, and it shrunk back in horror, seeing its own emancipatory weapons turned against itself, from the devolution of its greatest philosophy, that of G.W.F. Hegel, into the radical ferment of the 1840s, leading to Karl Marx. Whereas capital had, from Tudor England via the French Revolution to various countries (e.g. Spain) into the 1840s aggressively closed down monasteries and expropriated vast church lands, its ideologues responded to the “specter of communism” by a growing flirtation with religious revival and a new irrationalism (admittedly mild indeed by comparison with the religious revival and new irrationalism of the past three decades.)

Such mystification, the frenetic ideological inversion of true human possibilities forced back into capitalist relations, had already achieved enormous proportions during the 1945-1970 postwar boom, perhaps best embodied in the aesthetics, theory and practice of “high modernism”. This was, East, West, North and South, the era of the “enlightened planner,” whether in the New York City of Robert Moses, the “science cities” of the former Soviet Union, the white elephant foreign-aid driven construction of huge, little-used steel plants and freeways to nowhere in the Third World development regimes of Nasser and Nehru, or the eerie silence of Oskar Niemeyer’s technocratic dream of Brasilia (like his similarly eerie headquarters of the French Communist Party in the Paris suburbs). Capital recovered from its brush with oblivion right after World War I, and the long decades of crisis up to 1945 necessary to re-establish global accumulation, with the pseudo- rationality of social planning of experts: the grey faceless bureaucrats of the British Labour Party and its welfare state, the arrogant technocrats of France’s “trente glorieuses,” the Stalinist bureaucrats of successive Soviet five-year plans and the promise of “goulash communism,” the “defense intellectuals” and Robert McNamaras of America’s world military sprawl. It was the era of triumphalist pseudo-rationality in ideology, from brain-dead logical positivist philosophy via the onslaught of mathematics in neo-classical “economics” to the spare formalist austerity of modernist literature, art, architecture and music, these latter carefully expunged of the radical social dimension that animated or seemed to animate some currents of modernism in the years after World War I. Only a few, in this celebratory atmosphere, were aware that, since 1848, the only real rationality was that of the self-conscious global praxis of the revolutionary working class, but while the working class began its regroupment in the wildcat strike movement from the 1950s onward, dominant ideology continued to tout the luminous future of productivist technocratic modernism, a brilliant encampment of the hidden potential of “the beach” hidden “under the paving stones,” as one wall poet lyricist in Paris in May 1968 put it.

What, then, is one to say about the task capital faced in mystifying its superannuation after it managed to contain the worker revolt of 1968-1977? Every phase of capitalist ideology since 1848, but especially since 1917, has been forced to adorn itself with fragments borrowed from the defeated revolutionary surge. One recalls Louis Napoleon’s promotion of worker organization and even of a French delegation to the early congresses of the First International. Interwar fascism was adept in borrowing the trappings and mass propaganda methods of the workers’ movement it crushed. One might then characterize the three decades after World War II, whether in welfare statist, Stalinist or Third World development guise, as the “realization” the Social Democratic Gotha Program denounced by Marx in 1875.

The capitalist counter-offensive since the late 1970s is the one closest to us, and thus merits a more detailed accounting. All these social and cultural phenomena, from the breakup of cities into suburbia and exurbia, the proliferation of shopping malls and “edge cities,” the “reconquest” of the inner city, previously abandoned by the middle classes during the postwar boom, in the form of worldwide gentrification and expulsion of the poor to trashy sprawl, by way of the overt corporate takeover of “education,” to the even greater privatization and atomization of people by individual technologies and the vast ocean of trivia they “communicate,” must be understood from the vantage point of the potential human material community whose inversion they are. And it must never be forgotten that these “post-modern” phenomena, in North America, Europe and East Asia, touted as they are as “growth,” coexist on a world scale with the “planet of slums,” in Mike Davis’s phrase.

What is noteworthy about the past three decades is the way capital appropriated for itself much of the ideological froth of the defeated and co-opted movements of the 1960s.[4] It was not the first time that the rebellion of the alienated middle classes helped to pioneer the next phase of accumulation. In the 1930s it was exactly these classes who populated the bureaucracies of the emerging welfare state. After the late 1970s, one might say that the personal computer, for the well-to-do classes of the “advanced” capitalist sector, will stand as a symbol of this phase of accumulation as the automobile did for the earlier period. Yet the computer, like the automobile before it, was much more than a technology, bound up as it was with a whole ideology of freedom. That latter ideology was the “revolution” against “bigness” and “bureaucracy” and “hierarchy,” against the “Organization Man” and the “grey flannel suit,” once among the battle cries of the 60s New Left. Where the earlier movement, both in its political as in its Bohemian/ counter-cultural form, had counterposed hedonistic consumption to the then-dominant “Puritanism,” here was the capitalist class and its minions themselves, headed by its Wall Street and City of London yuppie vanguard, plunging into designer drugs, gourmet restaurants and high fashion S+M. Not much was said about the ever-lengthening work week, both for these “creative classes” touted by hip and vacuous social theorists (e.g. Richard Florida), not to mention for the two- and three-paycheck working class family that was the road kill of the “new economy” and the “information superhighway”. And for the “creative classes” and many others, the PC, cell phone and Blackberry eliminated the antagonism between work and leisure, not in Marx’s “all-sided activity,” but as 24/7…work.

The quasi-totalitarian incorporation of failed rebellion reached into every aspect of life, from chic New York restaurants in some former warehouse district, with photographs of 1930s breadlines as interior decoration, to the obliteration of the offbeat café or independent bookstore by Barnes and Noble. Huge shopping malls appeared with little or no service personnel, let alone people knowledgeable about the merchandise, in cavernous halls of commodities; every business and state agency able to do so replaced receptionists with endless telephone trees of irrelevant options and interminable waits, cutting costs by forcing unpaid labor time on those they ostensibly “served”; all the “oppositional” culture of the past, from blues and jazz to once-subversive books was served up under cellophane at Borders. In the name of the new, ultra-reified hype of “information” (as if books such as Hegel’s Phenomenology of Mind or Marx’s Capital constitute “information” side by side with the latest Tom Peters management manual), libraries shredded millions of books to move into reduced, wired space. Arrogant Silicon Valley CEOs and their publicists who had always hated books and serious thought touted the “paperless” economy of the new millennium. Millions of “middle management” jobs (admittedly of no redeeming social importance) disappeared through high-tech downsizing, and those who lost them disappeared into the recycled suburban oblivion covered over by the chorus of the “new economy”. Universities remade “liberal” education as extended vocational training for their “customers,” handing over the tattered remnants of the old humanities to the “everything is corrupt” mantras of the post-modern deconstructionist Lumpenintelligentsia, expert in projecting its (no argument- very real) corruption onto the very emancipatory universal movements in history—revolutions—from which Insurgent Notes draws inspiration. Such ideological decay helpfully diverted attention from the accelerating decay of American infrastructure—the “old economy” of sewers, subways, street and road pavement, bridges, New Orleans levees, or tenement apartment buildings. Perhaps most astounding in this whole ideological facelift was the emergence of the MBA and computer geek and investment banker, figures widely reviled and ridiculed in the climate of the 1960s, as little less than culture heroes and “revolutionaries”. The forgotten “absent-minded professor” ,still (in some cases) having a whiff of the old (and now passé) humanism, was replaced by the sleek, tanned, cynical “radical” post-modern literary theorist, networking his or her way to tenure and from conference to conference.

Modest houses and neighborhoods built for workers in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, in the post-1970s reoccupation of the inner city by the dual income /no kids yuppie class, were refurbished in the general “quotation” of the culture of the past, stripped bare of the vibrant street life that had once made them bearable for their earlier inhabitants. (Adding insult to injury is the little-discussed “fact” that the typical US working-class family spent 15% of its income on housing in 1950, and spends on average 50%—usually one full paycheck—today.) This new dispensation also involved a massive war on memory, from the proposal to turn Auschwitz into a theme park to the malling of the site of the great street battles of San Francisco’s 1934 general strike. Radical longshoremen in the 1950s had mixed with literary Bohemia in San Francisco’s North Beach or at New York’s White Horse Tavern, but today the fully-containerized ports have relocated far away, with one-tenth the number of workers, and one hardly imagines a similar mixing in those old venues of the yuppies and the zoned-out workers from the nearest Macdonalds.

Just as capitalism, through primitive accumulation, had always lived in part off the looting and destruction of pre-capitalist social formations, so had bourgeois culture in its ascendant centuries lived off pre-capitalist cultural strata (e.g. its mimetic relationship to the European aristocracy). As capital turned inward on itself, the self-cannibalization of its social reproductive base since the late 1970s was echoed with eerie concision in the self-cannibalization of its once-emancipatory culture in the ideological Ebola virus spread by the post-modern nihilists and deconstructionists, the Foucaults, the Saids and the Derridas. As Marx said long ago, “the ruling ideas of every epoch are the ideas of the ruling class.”

VIII. Class Regroupment and Its Enemies: Porto Alegre, NGOs and the World Social Forum against the Global Working Class

This cultural offensive has not been without its political counterpart. The non-Marxist left has repeatedly been essential to capitalism in reshaping it for a new phase of accumulation. One need only remember Proudhon and his 150 years of influence on worker-run cooperatives[5] in a capitalist framework, or, closer to our own time, the role of Social Democracy, Stalinism and Labourism (and even fascism, from the ex-leftists such as Mussolini who initially forged it) in laying the foundations for the post-1945 Keynesian welfare state.

But just as in the way that, in the 1950s and 1960s, many leftists shifted their hopes (during an apparent period of working-class ebb in the West) to romanticized guerrilla movements in Latin America, Africa and Asia, only to be bitterly disappointed by their results and above all to be taken aback by the working class explosion in Europe and the U.S. in the 1960s and 1970s, the shift of emphasis in the 1980s and 1990s shift to social movements, in a radically transformed world context, grows from a similar ebb. The world working class, and only secondarily the social movements, holds the key to any positive 21st century future we wish to see. The newly-created working classes that have emerged in parts of the Third World in recent decades naturally mean that the next working class explosion will not look like the last one, any more than the last one looked like those of the interwar period. Without such an explosion, the social movements will only be, as they have seemed so far to be in Latin America, mere adjuncts to a newly reconstituted capitalist state, possibly with Chavez’s Venezuela or even Lula’s Brazil as a paradigm.

If world capitalism manages to reconstitute a viable framework of accumulation out of the current crisis, many of the new social movements—identity politics built around race, ethnicity, gender, alternative sexuality, energy and the environment, hostile to class content—will have played such a role. The polemical fire of the World Social Forum and lesser venues is mainly aimed mainly at neo-liberalism and neo-conservatism, not at capitalism and nor the global Keynesians Stiglitz, Sachs, Soros, Krugman et al. who are among the leading candidates to reshape a future capitalist restructuring at the expense of the working class and its potential allies, as their predecessor J.M. Keynes helped do in the 1930s and 1940s. The World Social Forum’s exemplary proponents of “global justice” include the Stalinist Fidel Castro, the petro-Peronist Hugo Chavez, or the former Khmer Rouge admirer Samir Amin.

One proponent of such “progressive forces” wrote recently, and typically:

”…the challenge for progressive forces, as ever, is to establish the difference between ‘reformist reforms’ and reforms that advance a ‘non-reformist’ agenda. The latter would include generous social policies stressing decommodification, and capital controls and more inward-oriented industrial strategies allowing democratic control of finance and ultimately of production itself.”[6]

If such a program is to have “capital controls” and “democratic control of finance” one wonders how serious “decommodification” is to occur, since commodity production is central to the existence of capital and finance.

New social movements are nowhere so prominent or successful as in Latin America, where a new populism has been on the ascendant in recent years. Lula was certainly a pioneer of this trend,[7] from the social-movement orientation of the early years of the Brazilian Workers’ Party to his…disappointing …(if predictable) performance once in control of the state. The Argentine piqueteros overthrew a government in December 2001, and then, after failing to replace it with anything else (pace John Holloway[8]) split into a right and left wing, with the right wing now administering state workfare and welfare programs for the remade (and Peronist) governments on a highly politicized basis. Evo Morales in Bolivia seems similarly to be using the momentum of the social movements that stopped the privatization of natural resources in 2003 (setting aside for a moment the implications of state property) for a new legitimation of the state. And the most elaborate development of this trend culminates, to date, in Hugo Chavez’s Bolivarian “socialism of the 21st century,”[9] with the standing professional army at its core, complete with Cuban advisors, using ground rent revenues from oil to finance a new version of the Peruvian (1968-1975) military model which was one of Chavez’s foremost influences. A new form of state paternalism is being reconstituted on the basis of the social movements, replacing the old authoritarian state paternalism (e.g. Peron, Vargas) which is no longer viable.

Yet side by side with this fanfare, new workers’ struggles have emerged in Latin America. In 2006, the Oaxaca uprising, set off by the teachers’ union but quickly transformed into an urban insurrection, brought to the fore a radical “asembleista” element over months, more or less simultaneous with the weeks-long investing of downtown Mexico City after the stolen election of that year, a mass occupation that went well beyond the left-bourgeois party (the PRD) of the aggrieved loser Lopez Obrador. There have been general strikes in Ecuador and Peru. There have been a few exemplary strikes in Venezuela sounding a discordant note in the hoopla over Chavez (a hoopla increasingly more fervent among his foreign cheerleaders than in the Venezuelan masses). In Argentina, in 2001-2, the piqueteros (despite their shortcomings mentioned earlier) and the creative methods of struggle beyond the factory they had developed earlier brought down the Peronist state for a brief moment before demonstrating their own inability to go any farther. Aspects of this Latin American ferment have also percolated into the U.S., as in the May Day mobilizations of Latino immigrants in 2007 and 2010.

Social movement theorists reiterate again and again that “organized labor” can no longer be the unifying force for a much more atomized, casualized and dispersed workforce that it once was.

Insurgent Notes is not preoccupied in the slightest with “organized labor” but with the working class as a whole. It is important never to lose sight of the historical backdrop of this shift of emphasis from the working class to the new social movements. Again and again the pattern has emerged, as in Brazil (1978-83), Poland (1980-81) and Korea (1987-1990) of a sort of culmination of “old style” industrialization (the “mass production worker” as some say today) of an explosion of wildcat strikes, important victories, followed by a capitalist counter-offensive that boils down to the full implementation of the all-too-familiar out-sourcing, casualization, and de-industrialization ad nauseam. In Brazil in 1983, the CUT (the main union federation, including Lula’s metal workers’ union) was riding the prestige of those strikes. By 2000, the CUT was reduced almost to social work, teaching laid-off auto workers how to start fruit stands around the downsized factory gates. Similar the landless movement (os sim-terra as they are called in Portuguese) has combined some important successes in the face of harsh repression with the repeated problem of peasants falling away once they have acquired their piece of land. In South Korea, the late 1980s strike wave gave way to a proliferation of NGO’s, “peace activists” and chatter about “civil society”.

The new social movements emerged in the early 1980s to fill the gap left by this devastating counter-offensive of capital against the world working class. To take only one paradigmatic example, FIAT in Italy spent billions in those years shifting from the big Turin factories to cottage production producing as many or more cars with far fewer workers, spread out in small towns. The wildcat wave of the late 1970s was broken. It could almost be a paradigm for an epoch. Capital is prepared to destroy society to continue as capital.

In recent years, in addition to Latin America, there has been an impressive groundswell of strikes around the Third World (textile strikes in Bangladesh and Egypt, the TEKEL strike in Turkey, general strikes in Vietnam, struggles in Gurgaon (India)[10] the role of the Indonesian working class in the overthrow of Suharto in 1998, 70,000 “incidents” a year in China involving e.g. privatization, looting of pension funds).[11] Outsourcing, casualization and temp work has obviously blurred the boundaries of the classical, relatively stable blue-collar proletariat of the pre-1980 period. Whatever their condition, the blue-collar workers of China, India, Brazil, or Southeast Asia movements, not to mention the workers of the ex-Soviet bloc which have become available to capital accumulation in recent decades, are already part of the emerging next proletarian offensive.

IX. Summary and Program

Faced with this rising tide of an opposition groping for coherence, and fearful of provoking further escalation through five-thumbed immediate confrontation and repression, capital in the recent period has rediscovered the strategy and tactics of the Italian industrialists faced with the factory occupations of 1920: fold their arms and wait. As in Argentina in 2002 or in Oaxaca in 2006, or—on a smaller scale—the 77-day Ssangyong Auto factory occupation in South Korea in 2009, the basic message from the capitalists and the state to the insurgents is: “you’ve taken over the factory, the town, the country? Fine. Are you ready to run it yourselves?” (One recalls a similar meeting in January 1919 between British Prime Minister Lloyd George and the heads of the British Trade Union Council—not that the latter ever had any intention of taking over anything) When the insurgent movement fails to rise to that challenge, tempers fray, patience is exhausted, the professional leftists capture the mikes, people tire of endless meetings, however democratic (all this drift helped along by whatever repression the state can muster politically while awaiting its moment to strike back massively) and the movement collapses. In these recent instances (unlike Italy in 1920), a massive bloodletting has not been necessary after the defeat (which hardly means that selective deadly repression did not follow). The point is rather that, without a “programmatically-armed” militant stratum, one that will not spontaneously converge in the run-up to the final showdown, without a concrete idea of “another social project” (to use a certain language), the movement melts away, often with relatively few shots fired. (This is not to deny the often important and creative role of “spontaneity”[12] in the early, ascendant phase when the movement seems to go from strength to strength.)

This absence of a broad-based alternative to rule by elites—whether by the bourgeoisie or by professional leftists prepared to outlast everyone else in interminable meetings and then vote their agenda at 2 AM—has always been the basis of class society, whether “reactionary” or “progressive”. Passivity, voluntary or induced, is always the handmaiden of “bureaucracy”. And in our view, the best antidote to such a defeat is the widest possible propagation of the concrete programmatic aspects of a different “social project” and practical testing of such knowledge on the way to working-class power. Our aim is to help the working class become the ruling class in the process of dissolving all classes.

To summarize:

- capital since the wildcat rebellion of the 60s/70s (with extensions in such places as Brazil, Poland, Korea) has been engaged in a quasi-conscious counter-strategy to break up the centers of proletarian concentration, creating as much as possible the new atomized, casualized, dispersed wage-labor populations for whom the one paycheck family, long-term job security, benefits, secure housing, education and”aspirations” (however bourgeois) for the nextgeneration are not even a memory.

- This is closely tied to the financialization of capitalism. This is not ‘normal’ capital accumulation. It is destroying the material basis of social reproduction, both in terms of labor power and means of production (including infrastructure and nature).

- This development expresses the fact that value (in Marx’s sense) was already superannuated in the crisis of the 60s/70s, and that capital on a world scale has to perform massive retrogression to reconstitute an adequate rate of profit, not in the debt-for-equity restructurings and mergers and acquisitions, but in real production and reproduction.

- The programmatic question can obviously not be one of rebuilding the old mass production factories as such. No one misses the assembly line, and automobile- centered production and consumption has already ravaged enough “social” space. It has been pointed out often enough that, despite the creativity of the wildcat movements from the 50s to the 70s, most of the left (myself included) theorized the factory worker as worker, and not as the leading force in a striving to break the logic of factory work

to accede to a Grundrisse-like “activity as all- sided in its production as in its consumption,” i.e. communism. Nonetheless, while recognizing that mass production seemed to produce something much closer to class consciousness and class

action than what we have seen since, we can also recognize that breaking the old “social contract” of the post-World War II period also broke the conservatism built into attachment to one job, a mortgage, etc. that must have inhibited as much solidarity as it fostered, in one factory, in one industry. This has led, in some countries such as France and Italy, to movements of working-class youth, who will never have the stability their parents had, using this precarious mobility as a way of building city-wide “flying picket” movements centered on whole cities as opposed to one big factory or industry. - In an “Hegelian Marxist” perspective, i.e. a realistic perspective, the reality of the world working class (Gesamtarbeiter) is the current potential of the world working class

to build a society beyond value production. That is the reality against which capital has been fighting since the 60s/70s, and in fact since the early 20th century. It determines the true framework of struggles today. A Stiglitz- Sachs et al. inspired global Keynesianism, built on the new social movements, would be the exact update of the Keynesian reorganization of capitalism coming out of the transitional crisis of 1914-1945. - Our task must be to articulate the full implications of that positive power which lies beyond the disorientation of today. We must further try to show where that potential surfaces in micro-ways in the struggles of the present. For example, the suburban youth of the Paris region routinely ride free on the trains in and out of the city, and physically confront the train personnel who are obliged to collect fares. A campaign for free public transportation could unite such elements, freeing the train personnel from an important part of their “cop” role. The same could be said for many toll-takers of daily life, to give only one example of where proletarians are set against sub-proletarians.

What follows in conclusion, then, is a program for the “first hundred days” of a successful proletarian revolution in key countries, and hopefully throughout the world in short order. It is intended to illustrate the potential for a rapid dismantling of “value” production in Marx’s sense. It is of course merely a probe, open to discussion and critique:

- implementation of a program of technology export to equalize upward the Third World.

- creation of a minimum threshold of world income.

- dismantling of the oil-auto-steel complex, shifting to mass transport and trains.

- abolish the bloated sector of the military; police; state bureaucracy; corporate bureaucracy; prisons; FIRE; (finance- insurance- real estate); security guards; intelligence services; cashiers and toll takers.

- taking the huge mass of labor power freed by this to radically shortening of the work week

- crash programs around alternative energy: (in the long run, if possible) nuclear fusion power, solar, wind, etc.

- application of the “more is less” principle to as much as possible (examples: satellite phones supersede land-line technology in the Third World, cheap CDs supersede expensive stereo systems, etc.).

- a concerted world agrarian program aimed at using food resources of North America and Europe and developing Third World agriculture.

- integration of industrial and agricultural production, and the breakup of megalopolitan concentration of population. This implies the abolition of suburbia and exurbia, and radical transformation of cities. The implications of this for energy consumption are profound.

- automation of all drudgery that can be automated.

- generalization of access to computers and education for full global and regional planning by the associated producers

- free health and dental care.

- integration of education with production and reproduction.

- the shift of R&D currently connected with the unproductive sector into productive use

- the great increase in productivity of labor will as make as many basic goods free as quickly as possible, thereby freeing all workers involved in collecting money and accounting for it.

- a global shortening of the work week.

- centralization of everything that must be centralized (e.g use of world resources) and decentralization of everything that can be decentralized (e.g control of the labor process within the general framework)

- measures to deal with the atmosphere, most importantly the phasing out of fossil fuel use by 3 and 6

Once again, at this stage, such programmatic points are only suggestive and wide open to debate, focusing not on “forms of organization” but on the content of a world beyond value, in which “the multiplication of human powers is its own end.”[13]

- [1] While we do not locate ourselves in the Bolshevik tradition, of which the contemporary remnants of Trotskyism are –in contrast to Stalinists and Maoists—the serious continuity, we hardly dismiss Lenin and Trotsky out of hand, as many libertarian communists tend to do. Lenin’s intransigeant internationalist stance in 1914 and his 1917 April Theses, like Trotsky’s almost unique application of the theory of permanent revolution to Russia, well before 1917, were revolutionary moments. What we reject in Leninism and Trotskyism would take us far afield, but the fetishization of organization and “leadership” (in the case of Trotsky) are obvious starting points for our critique. ↩