Archive of Radical America magazine, a left-wing journal published in the US 1967-1999. It began life as an official journal of Students for a Democratic Society (SDS) but later became independent.

Radical America was founded by members of SDS in 1967. The initial editors were Paul Buhle and Mari Jo Buhle in their graduate school days, operating in Madison, Wisconsin. In the first few years, it served as the "unofficial journal of SDS."

Initially, subscriptions were sold at a discount rate to national SDS members. The Buhles relocated to the Boston, Massachusetts area, and brought the journal with them. By the time of the Boston move the journal was independent from the SDS.

The journal, published in Somerville, Massachusetts, focused on topical issues of concern to the left and society at large, such as women's liberation and working class radicalism. Beginning in 1970, each issue had a dedicated focus upon one issue. Mainly, during the 1970s, the journal evolved in a direction concerned with New Left issues, rather than traditional, Old Left concern with strengthening ties with trade unions. It was particularly active in the 1970s, as authors related the experiences of feminist activists and autonous work-place activists.

Many of the PDF issues here have been taken from this website and we are grateful to Reddebrek for posting them here.

Issue 2 of the first volume of Radical America published in September-October 1967, most articles concern the Industrial Workers of the World.

Constituent articles:

- They didn't suppress the Wobblies (Thompson, Fred)

- Wobblies and draftees The I.W.W.'s wartime dilemma, 1917-1918 (O'Brien, James P.)

- American liberalism in transition, 1946-1949 an annotated bibliography (Buhle, Mari Jo)

- Toward history a reply to Jesse Lemisch (Scott, Joan Scott, Donald)

- New left elitism a rejoinder to the Scotts (Lemisch, Jesse)

- Summary list articles in American Radical History, January-August 1967 (Buhle, Paul)

- A paperback approach to the American radical tradition I (MacGilvray, Daniel)

Attachments

Comments

Hey, many thanks for this, just a quick note that the volume number should be written in two digit formats as there were more than nine volumes. And also the Radical America tag should be in the "authors/groups" box rather than the tags box. Cheers!

An article by Fred Thompson contesting the myth that the IWW was smashed by repression during World War I.

There is a widespread misunderstanding that the government and big business suppressed the IWW during World War I. They tried. They hurt and hampered, but they did not suppress. The record is a practical subject for study by those who find themselves unpopular with those in power today.

The IWW was used to the lawlessness of "law and order" from its birth in I905. In the summer of l9l9 opposition grew fierce. The IWW faced bullpens and stockades, mass "deportation" of the Bisbee miners to the desert of New Mexico, frequent arrest by immigration authorities of anyone suspected of being a foreigner, and the intervention of federal troops. In September the federal authorities raided the national office and all branch offices, collecting five tons of evidence to use against those it named and convicted on three mass indictments in Chicago, Wichita and Sacramento. In the immediate postwar years the IWW was victimized by what the Undersecretary of Labor called the "deportation delirium," by the general rabid anti-radicalism, by a lynching raid on the lumberworkers' hall in Centralia,, Washington, and subsequent manhunts, and even more by the passage of criminal syndicalism laws in various states and the arrest and trial through l923 of far more members under these state laws than had been tried under the earlier federal enactments. One can find this story detailed in the appropriate chapters of Perlman and Taft, History of Labor in the United States, Vol. IV;in Taft's article on Federal Trials of the IWW, Labor History, Winter, I962; or in Michael Johnson, “The I.W.W. and Wilsonian Democracy," Science § Society, Summer, I964; also in Eldridge Foster Dowell, History of Criminal Syndicalism in the United States; and most readably in KornbIuh's, "Rebel Voices."

During all this repression the IWW grew. Its peak membership was in 1923. It sunk rapidly the following year, not from repression which had eased, but from internal disputes. And it is still in there trying.

The academic fiction that the IWW was crippled by wartime persecution rests on an overestimate of wartime strength. The IWW has never been very large. Its smallness, coupled with the mark it has made on American labor history, shows a handful enrolled in it were more effective than if they had been enrolled elsewhere. Its prewar peak in l9l2, the year of the big Lawrence strike, was an average membership for the year of between eighteen and nineteen thousand. The defeat in Paterson took the last penny it could raise, and the depression that followed almost killed it in 1914. The European war helped it step up a campaign among agricultural workers in 1915, and to branch out into lumber and iron mines the following year, and to grow among copper miners and in the oil fields in l9l7. It tied up copper mining and, in the northwest lumber industry shortly before the September l9l7 raids.

The following calculation of membership from l9l6 through l924 is based on a percapita payment of seven and one half cents per month per member to the general organization. The periods used are those the national office used for cumulative financial statements, usually for the information of a general convention. The average dues-paying membership for any period would have been somewhat higher than that shown because some unions were always behind on percapita, and conventions usually "excused" the non-payment so it was not made up later.

Taft, Labor History, Winter, I962, page fifty-eight gives some figures for the five month period of April, l9l7 to September,1, l9l7, showing dues paid of $75,4l9.75. Since dues were 50¢ per month or $2.50 For the five month period, this figures out to a wartime peak of 30,168. The same source shows 32,000 members initiated in the same five months, but evidently they paid dues only for a month or so, and while adding to RTE revenue did not do much to swell membership. The statement is often made that at this time IWW membership was about 100,000, e.g. in Michael R. Johnson, Science & Society, Summer 1964, p.266: "On Sept.l, l9l7, the IWW possessed between 90,000 and 105,000 paid-up members

However, the purpose of this article is not to show how small the IWW has been, but to show that during this period of repression it actually grew. What gave the IWW this capacity to resist suppression?

Senator Borah spoke about the difficulty of jailing a mere understanding between workingmen. His oft- quoted remark gives part of the answer. The fact that the hardcore members of the IWW “knew what the score was”, and were dedicated to their ideals, must be counted,too. Democracy, organized self-reliance, and local autonomy explain more, and the fact that the employers wanted these men back at work explains still more.

Had the IWW been a highly centralized organization, the September l9l7 raids and the arrest of its officers, staff members, editors, speakers,etc, would likely have knocked it out. They were replaced, so far as they were replaced at all, by men direct from the point of production, who can be assumed to have sensed the feeling of the man on the job somewhat more accurately than their predecessors. Solidarity, the IWW paper, came out October 13, 1917 with a long list of those arrested, but the editor who replaced the jailed Ralph Chaplin had the good judgment to run on the first page the following wire from Philadelphia: “Out last night, Nef will be out today. Rush five thousand dues stamps and two thousand dues books --Doree.” From there on, there was a growing emphasis on the practical, and a discarding of leftish rhetoric, without ever losing sight of such ultimate aims as a new social order.

They proved it is very practical to provide as much local autonomy as the needs for coordinated effort can permit. The return to the woods in September, 1917 illustrates the point. The lumber workers had struck in early July. They were getting hungry, and weary of being run around by town bulls and federal troops and being herded into stockades. They decided to go back to the lumber camps and continue the struggle there. The outstanding demand was for the eight-hour day. Some took whistles with them, blew them at the end of eight hours, walked into camp, and, if they were fired, they switched places with men from other crews playing the same general sort of game, until they had eight hours, showers, better food, and better pay. There was no fixed pattern what to do, each crew used its own best judgment.

Neither repression nor resistance to it was uniform. The greatest efforts to get rid of the IWW came in the lumber, oil, copper and iron mining industries--places where unionism was relatively new. Where the IWW was organized in fields where unionism was more taken for granted, it continued, as on the docks of Philadelphia where it retained job control up to 1925, In the iron mines of the Mesaba Range and Michigan, its 1918 strike was met with a wage increase at the request of the government, to head off the strike. In the oil fields it fared poorest. In copper it was reduced to minority union status, but press accounts of postwar strikes assign it major influence. In the lumber Industry its strength grew, despite Centralia and the subsequent man-hunt, up to the calling of a strike by a "militant minority" against majority judgment in September I923. This radical disrespect for democracy in its ranks precipitated the destructive dissensions of I924 and proved far more harmful than all the efforts at repression and the membership soon recognized this fact.

The variation in resistance to repression should prove helpful in any full scale study of how to avoid getting suppressed. The IWW survived all this to engage in the first strike to unite all coal miners it Colorado (see McClurg in Labor History, Winter, l963); to efforts among the unemployed in the big depression to assure that they would strengthen picket lines instead of breaking them, thus stimulating the first instance of union growth during a depression; major organization efforts in Detroit and Cleveland, with steady job control--and union contracts--in metal working plants in the latter from I934 to I950. Since then its membership has been largely "two-card," with recent welcome input from the young new left, and a current determination to get back to its old specialty of "conditioning the job" under its own banner.

Fred Thompson

Originally appeared in Radical America (September-October 1967)

Attachments

Comments

Constituent articles:

- Studies on the left R.I.P. (Weinstein, James)

- The rent strikes in New York (Naison, Mark D.)

- Comment (Gabriner, Robert)

- A paperback approach to the American paperback tradition (MacGilvray, Daniel)

- Leaflet the genius of American politics

- Books on the American labor movement, 1877-1924

Attachments

Comments

another winner, thanks

is there a Mark Naison tag? there should be maybe, there's more by him in the library here and he's still publishing, afaik

Constituent articles:

- Hazard, Ky. document of the struggle (Sinclair, Hamish)

- The Hazard project socialism and community organizing (Wiley, Peter)

- A revolutionary rent strike strategy (Naison, Mark D.)

- The meaning of Debsian socialism an exchange (Buhle, Paul Weinstein, James)

- The stray intellectual (Lowenfish, Lee)

- Did the liberals go left? (Buhle, Paul)

Attachments

Comments

Reddebrek

Put this in the wrong place could someone move it?

no problem, will fix it now. But for future reference, you are able to do this yourself just click "edit" then in the "book outline" section shifted round in there.

(Alternatively, if you can see the "outline" tab next to the edit one then you can just click that and move it around there)

Constituent articles:

- Evolution of the organizers some notes on ERAP (Rothstein, Richard)

- The Guardian from old to new left (Munk, Michael)

- Socialist opposition to World War I (Leinenweber, Charles)

- On the lessons of the past (Strawn, John)

Attachments

Comments

Constituent articles:

- The early days of the new left (O'Brien, James P.)

- The student movement in the 1950's a reminiscence (Schiffrin, Andre)

- Poetry & revolution (Wagner, Dave)

- A revolutionary strategy (Ewen, Stuart)

- The radicals' use of history II (Lynd, Staughton)

- Again, the radicals and scholarship (Wood, Dennis)

Attachments

Comments

Constituent articles:

- The historical roots of Black liberation (Rawick, George)

- Revolutionary letters #15 (DiPrima, Diane)

- Africa for the Afro-Americans George Padmore and the Black press (Hooker, J. R.)

- Document: C.L.R. on the origins

- Black editor an interview

- Boston Road blues (Henderson, David)

- New perspectives on American radicalism an historical reassessment (Buhle, Paul)

- The poets (Georgakas, Dan)

- I sing of shine (Knight, Etheridge)

- Convention resolution: Madison SDS

Attachments

Comments

Hi, many thanks for continuing to post these. However could you please make sure to keep the article titles consistent so that they automatically go in alphabetical order? They should go in the format:

Radical America #xx.xx: Issue name

where the "xx" denote the volume then the issue number in two digit format, and the issue name is given if it has an issue. I.e.:

Radical America #01.03: The New York rent strike

Also, the sector tag "journalism" is for journalism workers' struggles so unless that is what the issues are about please don't add that.

(Please don't take any of this as criticism, as we are very grateful, just some technical pointers!)

Constituent articles:

- The new left, 1965-67 (O'Brien, James P.)

- Chicago (Kryss, T. L.)

- Black liberation historiography (Starobin, Robert Tomich, Dale)

- Homage to T-Bone Slim (Rosemont, Franklin)

- Visualized prayer to the American God, #2 (Levy, D. A.)

- The universal incredible generational gap story (Beck, Joel)

- The STFU failure on the left (Naison, Mark D.)

- Black liberation & the unions (Glaberman, Martin)

- Images of the Socialist scholars' conference (Gilbert, James)

Attachments

Comments

Constituent articles:

- Toward a radical theory of culture (Gross, David)

- Notes on a radical theory of culture (Shapiro, Jeremy J.)

- Follettes & further (The Willie)

- The new left, 1967-1968 (O'Brien, James P.)

- Sitting on a bench in TSquare (Levy, D. A.)

- El cornu emplumado a narrative (Georgakas, Dan)

- Cartwheel flashes (Blazek, Doug)

- Three poets (Wagner, David)

- Suburban monastery death poem (Levy, D. A.)

- R.E. vision #2 fragment (Levy, D. A.)

Attachments

Comments

Constituent articles:

- Black Icarus (Williamson, Skip)

- Smiling Sergeant Death and his merciless mayhem patrol the battle story! (Shelton, Gilbert)

- God Nose in You am what you 'snot

- The meth freaks fight the Feds to the finish (Wilson, S. Clay)

- Scenes from the revolution Billy Graham preaches the dope mystics (Shelton, Gilbert)

- Poo-Poo Cushman (Lynch)

- Freak Brothers

Attachments

Comments

Constituent articles:

- French new working class theories (Howard, Dick)

- A dream of bears (Torgoff, Stephen)

- Anarchist (Torgoff, Stephen)

- Che Guevara (Sloman, Joel)

- Working class self-activity (Rawick, George)

- Literature on working class culture (Brumbach, Will Evansohn, John Foner, Laura Meyerowitz, Ruth Naison, Mark)

- Automobiles (Lesy, Michael)

- Working class historiography (Faler, Paul)

Attachments

Comments

Constituent articles:

- On the proletarian revolution and the end of political economic society (Sklar, Martin J.)

- Advertising as social production (Ewen, Stuart B.)

- Preface to The future of the book

- The future of the book (Lissitsky, El)

- Preface to Tasks of the Communist press (Breines, Paul)

- Tasks of the Communist press (Fogarasi, Adalbert)

Attachments

Comments

Constituent articles:

- RA Conference report

- Science fiction in the age of transition (Maglin, Arthur)

- Some comments on Mandel's Marxist economic theory (Mattick, Paul)

- Genetic economics vs. dialectical materialism (Howard, Dick)

- R.E. vision #8, part II (Levy, D. A.)

- Where is America going? (Mandel, Ernest)

- Epilogue to the new German edition of Marx's 18th Brumaire of Louis Napoleon (Marcuse, Herbert)

- Abolitionism (Lynd, Staughton)

- In revolt (Breines, Paul)

Attachments

Comments

Paul Mattick reviews Ernest Mandel's book Marxist Economic Theory.

Originally appeared in Radical America Volume 3, Number 4 (July/August 1969)

Attachments

Comments

Constituent articles:

- Theodor Adorno (Gerth, Hans)

- Althusser (Levine, Andrew)

- Comment (Glaberman, Martin Piccone, Paul Tomich, Dale Calvert, Greg)

- Rabbits (Kryss, T. L.)

- Plucking the slack strings of summer (Gitlin, Tod)

- Political preface to Sklar (Kauffman, John)

- We will fall toward victory always (Torgoff, Stephen)

- CLR James' modern politics (Wicke, Bob)

- With Eisentstein in Hollywood (Crowdus, Gary)

- Karl Kraus (Rabinbach, Anson)

Attachments

Comments

Constituent articles:

- What is youth culture? (Buffalo Collective)

- Technology, class-structure, and the radicalization of youth (Delfini, Alexander)

- From youth culture to political praxis (Piccone, Paul)

- Rifle no. 5767 (Rodriguez, Felix Pita)

- Rock culture and the development of social consciousness (Ferrandine, Joseph J.)

- Ho Chi Minh good-bye and welcome (Parsons, Howard)

- Stand still suitcase till I find my clothes (Gavon, Paul A.)

- Left literary notes masses old and new (Sonnenberg, Martha)

Attachments

Comments

Hey, thanks for continuing with this it's really great! Although please do not use the tag "social movements" for all of them. The social movements tag is for articles with the history of a social movement in, i.e. the anarchist movement in Japan, the movement against slavery in the US etc

Constituent articles:

- Introduction to 1970 (Rosemont, Franklin)

- Letter to the chancellors of European universities (Artaud, Antonin)

- Preface to the International Surrealist Exhibition (Breton, André)

- Excerpts from an interview with André Breton (1940) (Breton, André)

- Art poetique (Breton, André Schuster, Jean)

- The period of sleeping fits (Crevel, René)

- Excerpts from a review of The communicating vessels (Kalandra, Zavis)

- Hearths of arson (excerpt) (Calas, Nicolas)

- Surrealism and the savage heart (Bounoure, Vincent)

- Gardeners' despair or surrealism & painting since 1950 (Pierre, José)

- Introduction to the reading of Benjamin Péret (Courtot, Claude)

- The gallant sheep (Chapter 4) (Peret, Benjamin)

- The hermetic windows of Joseph Cornell (Rosemont, Penelope)

- Where nothing happens (Benayoun, Robert)

- The seismograph of subversion notes on some American precursors (Rosemont, Franklin)

- Electricity (T-Bone Slim)

- The devil's son-in-law (Garon, Paul)

- Such pulp as dreams are made on H.P. Lovecraft & Clark Ashton Smith (Parker, Robert Allerton)

- The neutral man (Carrington, Leonora)

- Dialectic of dialectic (excerpts) (Luca, Gherasim Trost)

- Surrealism a new sensibility (Mabille, Pierre)

- We don't ear it that way trace, 1960

- The invisible ray (excerpts) (Vancrevel, Laurens)

- The platform of Prague (manifesto, 1968) (excerpts)

- Notes on contributors

- Poems (Cesaire, Aimé Duvall, Schlechter Greenberg, Samuel Joans, Ted Legrand, Gérard Lero, Etienne Magloire-Saint-Aude, Clement Mansour, Joyce Mesens, E. L. T. Rosemont, Franklin Rosemont, Penelope Silbermann, Jean-Claude)

Attachments

Comments

Constituent articles:

- The American family decay and rebirth (James, Selma)

- Women's liberation & the cultural revolution (Kelly, Gail Paradise)

- Where are we going? (Dixon, Marlene)

- Women and the Socialist Party, 1901-1914 (Buhle, Mary Jo)

- Women, Inc. and women's liberation (Sanchez, Vilma)

- Project: company kindergartens (Sander, Helke)

- From feminism to liberation bibliographic notes (Altbach, Edith Hoshino)

Attachments

Comments

Constituent articles:

- Dear Herbert (Aronson, Ronald)

- Marcuse's Utopia (Jay, Martin)

- Notes on Marcuse and movement (Breines, Paul)

- Intellectual in the Debsian Socialist party (Buhle, Paul)

- Comments on Paul Buhle's paper on socialist intellectuals (Gilbert, James)

- Toward a critical theory for advanced industrial society (Schroyer, Trent)

- Poems (Temple, Norman)

- Poems (Sloman, Jose)

Attachments

Comments

CLR James issue of Radical America, a left wing magazine established by members of the Students for a Democratic Society (SDS).

Vol. IV, No. 4 MBV. 1970

Introduction by Martin Glaberman

PHILOSOPHY AND MODERN SOCIETY

Excerpt from Modern Politics (1960) ............ 3

AMERICAN SOCIETY

The Revolutionary Solution to the Negro Problem

in the United States (1947) ................ 12

Excerpt from State Capitalism & World

Revolution (1949) ..................... 19

Excerpt from Facing Rea/ity (1956) ............. 31

THE CARIBBEAN

The Making of the Caribbean People (1966) ......... 36

Excerpt from Party Politics in the West Indies (1962) .... 50

The Artist In the Caribbean (1959) .............. 61

LITERATURE & SPORTS

Excerpts from Mariners, Renegades & Castaways (1953) . . . 73

Excerpts from Beyond a Boundary (1963) .......... 67

SOCIALISM AND THE THIRD WORLD

Excerpt from Nkrumah Then And Now (forthcoming) . . . 97

Attachments

Comments

This is great Juan!

Gotta love that IWW union bug: "Abolish the Wage System; Abolish the State; All power to the Workers"

Radical America #04.05: Society of the Spectacle

Constituent articles:

- Separation perfected (Debord, Guy)

- Commodity as spectacle (Debord, Guy)

- Unity and division within appearance (Debord, Guy)

- The proletariat as subject and as representation (Debord, Guy)

- Time and history (Debord, Guy)

- The organization of territory (Debord, Guy)

- Negation and consumption within culture (Debord, Guy)

- Ideology materialized (Debord, Guy)

NB: This translation was criticised by the American section of the Situationist International in their poster To nonsubscribers of Radical America.

Attachments

Comments

Constituent articles:

- Benjamin Peret: an introduction (Rosemont, Franklin)

- The dishonor of poets

- The factory committee

- Poetry above all

- The thaw a surrealist tale

- William A. Williams his historiography (Meeropol, Michael)

- Comment (O'Brien, James P.)

- A reading of Marx, II (Levine, Andrew)

- Comment (Tomich, Dale)

- Review of Armed struggle in Africa (Nzongola, Georges)

- Review of Walter Lowenfels (Blazek, Douglas)

Attachments

Comments

Article by Benjamin Péret arguing for the power of the factory committee as a vehicle for revolutionary change.

The following article was originally published in the French anarchist paper Le Libertaire on September 4, 1952. The first English translation appeared in Radical America vol. IV, no. 6, August 1970. Thanks to Don LaCoss for supplying the article.

No one will deny that capitalist society has entered a period of permanent crisis, which induces it to reassemble its weakened forces and to concentrate, more and more, all political and economic power in the hands of the state, by means of nationalizations. To this concentration of capitalist power, are we going to continue to oppose the scattered forces of the workers? To do so would be to run into definitive defeat. And one of the principal reasons for the present apathy of the working class resides in the interminable series of defeats suffered by the social revolution throughout this century. The working class no longer has confidence in any organization because it has observed them all at work, here and there, and seen that all of them, including the anarchist organizations, have revealed themselves to be incapable of resolving the crisis of capitalism - that is to say, of assuring the triumph of the social revolution. One must not be afraid to say that all of these organizations are outdated and no longer valid. On the contrary, only this very realization - the importance of which should not be reduced by more or less circumstantial considerations, nor by blaming others for the consequences of one's own errors - provides a point of departure from which we can truly prepare ourselves to revise all doctrines (which today share a substantial portion of outdatedness), perhaps resulting in a fundamental ideological unification of the workers' movement in the direction of the social revolution. It goes without saying that I do not by any means dream of a movement whose thought would be monolithic, but a movement unified from within, and in which diverse tendencies could enjoy the most ample freedom to manifest themselves.

On the other hand, it is no less true that action is called for immediately. This action must obey two general principles: first, it must facilitate the ideological regroupment mentioned above; and second, it must cease considering the revolution as the work of future generations for whom we are supposed to make the preparations. We are faced with this dilemma: either the social revolution and a new impetus for humanity, or war and a social decomposition of which the past offers only a few pale examples. History is granting us a breathing space the duration of which we do not know. Let us make use of it to reverse the course of the present degeneration and to bring about the revolution. The present apathy of the working class is only temporary. It indicates, at this time, both the workers' loss of confidence in all organizations, and a certain detachment on their part. It depends on us, as revolutionaries, to draw the lessons, which will enable this detachment to be transformed into active revolt. The energy of the working class asks only to exert itself. Nevertheless, it is necessary to give it not only an end - it has had a presentiment of this for a long time - but also means of attaining this end. If the task of revolutionaries is to bring about a fraternal society, this necessitates, beginning immediately, an organism in which this fraternity can form and develop itself.

At the present time, it is on the factory level that workers' fraternity attains its maximum. Thus, it is there we must act, but not in clamouring for a trade-union which is chimerical today, in the actual conditions of the capitalist world, and which, moreover, could only come forward AGAINST the working class, since the trade unions represent now only different tendencies of capitalism. In fact, a "united front" of the unions could happen only on the eve of the revolution - and would act against the revolution since the major unions would all be equally interested in torpedoing it to assure their own survival in the capitalist state. Henceforth, as integral parts of the capitalist system, they defend this system by defending themselves. The interests of the union are essentially their own and not those of the workers.

Moreover, one of the most powerful obstacles to a workers' regroupment and a revolutionary renaissance is constituted by the apparatus of the union bureaucrats, even in the factory, beginning with the Stalinist apparatus. The enemy of the worker, today, is the union bureaucrat every bit as much as the boss, who without the union bureaucrat, would most of the time be powerless. It is the union bureaucrat who paralyzes workers' action. And thus the first watchword of revolutionaries must be: Out the door with the union bureaucrats!

But the principal enemy consists of Stalinism and its union apparatus, because it is the partisan of state capitalism - that is to say, the complete fusion of the state and unionism. It is therefore the most clear-sighted defender of the capitalist system, since it outlines, for this system, the most stable state conceivable today.

Meanwhile, one should not destroy an existing organization without proposing another in its place, better adapted to the necessities of the revolution. And it is precisely the revolution that has taken t upon itself to show us, each time that it has appeared, the instrument of its choice: the factory committee directly elected by the workers assembled on the shop-floor, and the members of which are revocable at any time. This is the only organization which is able, without alteration, to direct the workers' interests within capitalist society while looking to the social revolution; and which is also able to accomplish this revolution and, once having attained victory, to constitute the base of future society. Its structure is the most democratic conceivable, since it is directly elected in the workplace by all the workers, who control its actions from day to day and are able to recall a member of the committee, or the entire committee, at any time, and choose another. Its creation offers the minimum of risks of degeneration because of the constant and direct control that the workers are able to exercise over their delegates. Furthermore, the constant contact between elected and electors favours a maximum of creative initiative in the hands of the working class, which is thus called upon to take its destiny in its own hands and to directly lead its own struggles. This committee, which authentically represents the will of the workers, is called upon to administer the factory and to organize the workers' defence against the police and the reactionary gangs of Stalinism and traditional capitalism. After the victory of the revolution, it is the factory committee which must indicate to the regional, national and international leaders (these also are directly elected by the workers), the productive capacities of the factory and its needs of raw materials and manpower. Finally, the representatives of each factory would be called to form, on the regional, national and international scale, the new government, distinct from the management of the economy, and whose principal task would be to liquidate the heritage of capitalism and to assure the material and cultural conditions of its own progressive disappearance.

At once economic and political, the factory committee is the revolutionary organism par excellence. That is why even its establishment represents a sort of insurrection against the capitalist state and its trade-union branches, because it assembles all the workers' energies against the capitalist state, and even assumes the latter's economic power. For the same reason one sees it burst forth spontaneously in moments of acute social crisis. But in our epoch of chronic crisis, it is necessary for revolutionaries to passionately defend and advocate this conception starting now if they wish, in the first place, to put an end to the meddling of union bureaucrats in the factories, and to restore to the workers the initiative of their emancipation. Let us therefore destroy the unions in the name of the factory committees, democratically elected by the workers in the plant, and revocable at any time.

Published in Red and Black Notes #20, Autumn 2004, this article has been archived on libcom.org from the Red and Black Notes website.

Comments

I don't speak or read French, but for those who do and are interested, here is the full text of Péret & Munis' book Les Syndicats Contre La Révolution:

http://raforum.apinc.org/bibliolib/HTML/Peret-Munis.html

The chapters in Péret's section before this one seem very good (from the Babelfish translation I made for myself) and could be good to add to the list on this thread.

Constituent articles:

- Introduction (Telos Staff)

- Towards and understanding of Lenin's philosophy (Piccone, Paul)

- Lenin and Luxemberg the negation in theory and praxis (Jacoby, Russell)

- The concept of praxis in Hegel (Paci, Enzo)

- Youth culture in the Bronx (Naison, Mark)

- On the role of youth culture (Heckman, John)

- Nations of youth culture (Buhle, Paul Morgen, Carmen)

- Youth culture and political activity (Delfini, Alexander)

Attachments

Comments

Constituent articles:

- American Marxist historiography, 1900-1940 (Buhle, Paul)

- W.E.B. DuBois and American social history evolution of a Marxist (Richards, Paul)

- The legacy of Beardian history (O'Brien, James P.)

- New radical historians in the sixties a survey

- Symposium on the teaching of history (Gordon, Ann)

Attachments

Comments

Constituent articles:

- Theses on contemporary American trade unionism (Booth, Paul)

- Old and new working classes (Hodges, Donald Clark)

- Working class communism (Peterson, Brian)

- Labor history reviews

- Reviews

- Index to Volumes I-IV

Attachments

Comments

Constituent articles:

- The demand for Black labor (Baron, Harold M.)

- Poetry (Yusuf)

- The league of revolutionary Black workers introduction (Perkins, Eric)

- Documents at the point of production

- From repression to revolution (Cockrel, Ken)

- Racism and the American experience (Starobin, Robert S.)

Attachments

Comments

Contemporary article on the League of Revolutionary Black Workers from Radical America which, though uncritical of their nationalistic sentiments, contains a lot of interesting information.

(Radical America Vol 5, #2 1971)

One finds it exceedingly difficult to introduce a new organization without seizing the opportunity to note that this is a black organization and, unlike all the others, offers a bright new strategy to the quiescent black movement. Black workers, with their important location in US industry and service, have demonstrated the need for a working-class movement within this advanced section of the American proletariat. Without recognizing the importance of black workers, any Leftist group or organization will be doomed to failure.

This introduction is designed to fill in some important gaps in our knowledge of the struggle. It is not a polemic, nor unfolding rhetoric proclaiming condemnations of America's futile attempt to deal with the race problem. Instead, the writer wishes the reader to know about this organization and its crucial importance in the development of a revolutionary movement in America. For far too long the plight of the black worker has been subjugated to the interests of the rulers and of their white working-class associates. What the League brings to the realm of analysis is surely nothing new (Need I remind our readers of Garveyism?), but is something which must be immediately realized that the American labor movement is now a memory, and something must be done now about its inability to deal with the problems of black workers.

With the establishment of DRUM (the Dodge Revolutionary Union Movement) in the Dodge plant at Hamtramck, Michigan in 1968, the white rulers and their infected proletarians got a taste of "a real black thang"! Wildcat strikes and electoral turmoil have characterized the automobile industry since. The League of Revolutionary Black Workers is indeed a timely response to the growing stagnation and alienation many of us now feel- black radicals and their frustrated so-called compatriots. Black labor has seldom been understood, and as Abram Harris remarked nearly half a decade ago: "An estimation of the role the Negro will play in the class struggle is futile if the economic foundation and its psychological superstructure from which issue antipathy or apathy are ignored." (1) The League perfectly understands this - that racism is the result of a two-fold process which involves economic inferiority and its internalization.

What is the League of Revolutionary Black Workers, and where did it come from? John Watson gives us the answer in an interview from the Fifth Estate:

The League of Revolutionary Black Workers is a federation of several revolutionary movements which exist in Detroit. It was originally formed to provide a broader base for organization of black workers into revolutionary organizations than was previously provided for when we were organizing on a plant to plant basis. The beginning of the League goes back to the beginning of DRUM, which was its first organization. The Dodge Revolutionary Union Movement was formed at the Hamtramck assembly plant of the Chrysler Corporation in the fall of 1967. It developed out of the caucuses of black workers which had formed in the automobile plants to fight increases in productivity and racism in the plant ... With the development of DRUM and the successes we had in terms of organizing and mobilizing the workers at the Hamtramck plant many other black workers throughout the city began to come to us and ask for aid in organizing some sort of group in their plants. As a result, shortly after the formation of DRUM, the Eldon Axle Revolutionary Movement (ELRUM) was born at the Eldon gear and axle plant of the Chrysler Corporation. Also, the Ford Revolutionary Union Movement (FRUM) was formed at the Ford Rouge complex, and we now have two plants within that complex organized. (2)

Centered in the extremely-important auto industry, the League has had an extremely wide and successful impact. It is now expanding its organizing activities to other areas - hospital workers and printers are now being organized, as well as the United Parcel Workers black caucus, which is one of the League's affiliates. Why this sudden turn from community organizing and the organizing of "street brothers and sisters", the black lumpen proletariat? The remarks of John Watson sum up the League's attitude toward this crucial and strategic shift in organizing policy:

Our analysis tells us that the basic power of black people lies at the point of production, that the basic power we have is our power as workers. As workers, as black workers, we have historically been, and are now, essential elements in the American economic sense. Therefore, we have an overall analysis which sees the point of production as the major and primary sector of the society which has to be organized, and that the community should be organized in conjunction with that development. This is probably different from these kinds of analysis which say where it's at is to go out and organize the community and to organize the so-called "brother on the street". It's not that we're opposed to this type of organization but without a more-solid base such as that which the working class represents, this type of organization, that is, community based organization, is generally a pretty long, stretched-out, and futile development. (3)

Community-based organizations throughout Black America have been failures. Stung by that fatal disease known as opportunism, many of these organizations either have dissolved or have been the subject of in-fighting for the pay-off. The ruling class has again demonstrated how it can pick up on anything and subvert it for its own use. It has again demonstrated that integration is a forced tool, and that no black man has the power to join white society without the sanction of the ruling class. (4) This shift is crucial.

For the last fifteen years the black movement has ridden the back of its middle-class leadership, following the white lead while they got the pay-off. The benefits (or bones) resulting from the "Civil Rights Movement" were distributed to the black middle class. In the fields of education, employment, and business, the black nouveau riche have made a small mark. The expansion of the black middle class is the unwritten policy of the white rulers. The black masses, predominantly workers (5), have been totally left out of this progress, and expressed their dissatisfaction by conducting their own "unorganized general strike" in the summers of 1966 and 1967.

The concessions granted to the new black rulers are meager, but they are real enough to raise, for the first time in a long while, the question of class antagonism. The League is responding to developing antagonisms of class in black America. Growing slowly is the black petit bourgeoisie, which consists of two wings: an educated black elite composed of technicians, managers, professionals, and others, and a small "ghetto bourgeoisie" composed of the owners of small ghetto shops and services. The ideology of this class is bourgeois nationalism which can be roughly summed up in the memorable words of Booker T. Washington in his speech before the Atlanta Exposition in 1895: "In all things that are purely social we can be as separate as the fingers, yet one as the hand in all things essential to mutual progress." (6)

Although this was said almost eighty years ago, it still characterizes the positions of most black nationalists. They see social revolution coming about in the disguise of white philanthropy and concern. To them the question of class struggle is an outmoded European idea which does not conform to their conception of black reality. The struggle lies in the institutional set-ups they can extract from the white paternalists, without ever stopping to think about the interest involved - that of the bourgeois nationalist or the white paternalist. Confusion and chaos have now replaced the moral glue which once held this class together, and there is no doubt that there is a huge gap in black leadership. (7)

With these facts to guide, the League has undertaken a very-difficult task - the organizing and leading of a national movement of black workers. Their local work clearly testifies to their national thrust. By organizing workers in strategic industries, the League plans to create the foundation for a black revolutionary party. Undoubtedly the perils of building a widespread national movement while laying the basis for a revolutionary party are difficult both to envision and to comprehend. But this is certainly one of their ultimate political tasks. The triumph of the downtrodden is inevitable.

The central theoretical concern of the League is the inevitable recognition of the black working class as the vanguard of the social revolution. As Ernie Mkalimoto suggests, the socialist revolutionary movement in the US must consider the black working class as leader.

Thus owing to the national oppression (principally through institutionalized racism as the dominant form of production relations) of black people in the United States, the black proletariat is forced to take on the most dangerous, the most difficult - yet absolutely necessary - productive work in the plants, the most undesirable and strenuous jobs which exist inside the United States today. The demands which it poses the elimination of economic exploitation (hence of capitalism) and of institutionalized racism (which thoroughly pervades the plant, not to mention North American society in general), and which allows capitalism to maintain itself, are more basic to the dismantling of US capitalist society than those of the white productive worker, who up to now has been able to defend his "white-skin privilege". That is why we say that any socialist revolution which is to be successful must take the class stand of the vanguard class of this revolution: the black proletariat.

Many white radicals and Iabor leaders will be unable to accept this position expressed by Mkalimoto (8). Why? Because the subtleties of racism have invaded their hearts and minds and prevent them from understanding the obvious. But it is this fundamental question which must be recognized before one begins to overthrow capitalism. Many so-called revolutionaries and others will say: This is a threat to the unity of the working class! This violates Marxism's first principle of international solidarity and all the rest. But with a basic understanding of the history of the black race, they will see how their arguments fail.

The League's basic position is revolutionary nationalism. One cannot forget that there are conservative and Leftist elements among the black nationalist spectrum. The League represents a Left-wing position. For those who are unfamiliar with the developing ideological debate within small black circles, revolutionary nationalism is an important and very complicated position to hold. Ernie Mkalimoto outlines revolutionary nationalism as follows:

A fusion of the most progressive aspects of the contradiction:

Bourgeois Reformism / Bourgeois Nationalism, Revolutionary Black Nationalism snatches the African-American from the puerile stage of Elizabethan drama, restores his sense of balance and direction in the universe, and sends crashing down to earth the clay idol of (Negro/American) emotional duality which has plagued the broad trend of black ideology from slavery to the present. From the activist wing of Bourgeois Reformism it takes the tactic of mass confrontation, struggles on all fronts, and integrates it into the existing order; from Bourgeois Nationalism comes the idea of the necessity for the development of national (revolutionary) culture and of both self-determination and self-reliance, as well as of the black world view which sees the struggle of African-Americans as inseparable from the struggles of all other peoples of color around the globe. The Revolutionary Nationalist views the concept of black nationhood not as any "sacred" unquestionable end in itself, but as a concrete guarantee to insure the dignity and full flowering of every individual of African descent. (9)

Revolutionary nationalism will indeed be difficult for the majority of whites to accept. It begins by taking into account the unusual degree of subjugation black people are forced to accept. It understands the unique feature of psychology and the internalization of economic phenomena. This indeed is timely. For one who does not admit the primacy of race compounded by class oppression refuses to recognize the most-central problem in American society.

The League dispenses with revolutionary rhetoric and commercial suicide, because that allows America to survive. The brother appearing on television and the revolutionary orator do not really contribute to capitalism's downfall; if anything they contribute to its maintenance.

By seizing on these images of blacks finally entering the mainstream, America controls the latent explosiveness present in most black men and black women. This is the current picture - black television, black business, black economic development, black executives - a swallowing of the "Negro revolution" by the imperialist giant.

America has created a grand illusion for most people - and black people are now subject to that illusion. The petit-bourgeois will not be able to succeed as long as it remains dependent on government and private help. The myth of the Negro capitalist is just that; but many of the brothers will not even acknowledge that. The myth of the "black capitalist and Negro market" must be dealt with. (10) There are few really-suggestive works on the problem of the class struggle in Black America. It is hoped that this issue will truly be a starting point for the emergence of a dialogue on this crucial question. The revolutionary nationalists have already begun.

The League is solidly committed to international struggle, but not without modifications. The international capital-versus-Iabor struggle is long ceased. It is now more the struggle of the rich nations versus the poor nations. It is no accident that the former are Europe and the US (with its Eastern satellite, Japan) and the latter are predominantly non - white countries. This is the major contradiction - of the West versus the non-West, and it is this contradiction which assumes the primary significance within the black workers' movement. This chief contradiction was aptly summed up in DuBois's often-quoted dictum:

The problem of the Twentieth Century is the problem of the color line. Their international commitment rests on the success or failure of the development of the national movement. This is how internationalism is introduced - by fully realizing the international importance of one's movement. Cuba, China, and Vietnam all testify to that fact, and so will the League.

Undoubtedly the above will confuse many. Yet the common knowledge of black workers is that white labor has left them in the cold. What characterizes the race relations of the American working class is a long history of betrayal and neglect. The fact is simple: Organized labor and the labor movement were instrumental in crushing black labor, A few remembrances would be in order.

The plight of the black slave and his super-exploitation has been skillfully handled in Robert Starobin's Industrial Slavery in the Old South, and I suggest that the interested reader come by a copy of this book. Following Emancipation, the black slave with his newly-acquired freedman's status entered the labor market. He was powerfully met by his poor-white counterpart. The black wretch possessed innumerable skills, and, as one writer noted, the black artisan held "a practical monopoly of the trades" throughout the South. (11) This represents an important chapter in radical history that deserves our full attention. For much of the Nineteenth Century, the black artisan controlled much of Southern Iabor, DuBois notes with his usual clarity the effects of this development:

After Emancipation came suddenly, in the midst of war and social upheaval, the first real economic question was that of the self-protection of freed working men. There were three chief classes of them: the agricultural laborers in the country districts, the house - servants in town and country, and the artisans who were rapidly migrating to town. The Freedmen's Bureau undertook the temporary guardianship of the first class, the second class easily passed from half-free service to half-servile freedom. But the third class, the artisans, met peculiar conditions. They had always been used to working under the guardianship of a master, and even that guardianship of artisans in some cases was but nominal, yet it was of the greatest value for protection. This soon became clear as the Negro freed artisan set up business for himself: If there was a creditor to be sued, he could no longer be sued in the name of an influential white master; if there was a contract to be had, there was no responsible white patron to answer for the good performance of the work. Nevertheless, these differences were not strongly felt at first - the friendly patronage of the former master was often voluntarily given the freedman, and for some years following the war the Negro mechanic still held undisputed sway. (12)

This progress was not lasting. As Northern industry invaded the South, it brought with it the strength of organized labor, The triumph of this organized labor in the South did not match its more-egalitarian works up North. The black artisan was crushed without the usual oratorical hesitation about such things as rights and equality. The labor movement crushed this small class of black artisans, subordinating them to the greedy desires of white labor and to the advantage of the capitalist. This is indeed a sad chapter in the American labor movement's history and one that still needs to be written in full.

By driving the black laborer from the skilled trades, organized labor forced him to become a scab in strikebreaking activities. The resulting friction was ominous of Detroit and Newark in 1967. (13) The black laborer was forced to accept the dual-wage system, menial jobs, and continual confinement within industry. There was little or no chance for upgrading or betterment. He was denied apprenticeships and was forced into separate local unions while his brother stole his livelihood lock and stock. Capitalism brought with it white labor which drove black labor to extinction in the skilled trades. And as black labor was driven from its work, it was also forced to leave home and migrate to the shining North - the land of golden opportunity.

The effects of black urbanization have yet to be understood. But one thing is sure. The coming of blacks to large industrial cities such as Chicago, Detroit, and Pittsburgh had important aspects. With the great war of 1914 came the great demand for black labor, Black labor came in herds to wartime industry. This was a timely break for black people. With work came money and the satisfaction of basic needs. Although blacks came in on the bottom and remained there, they did manage to implant themselves in industry and lay the groundwork for the future entrance of more black workers.

The tensions which developed out of the great migrations to the North are a part of a large transition made by Afro-Americans during the Twentieth Century. The shift was mainly from a rural proletariat to an urban industrial work force. This shift was dramatic, racial, intense. Rebellions were found everywhere from Arkansas to Illinois, And the results are not without strategic importance. The industrial shift had paved the way for a wide black revolutionary movement. The Garvey movement was a movement of the black masses - the black industrial, service, and domestic workers, as well as "the brother on the street". Garvey was totally rejected by the black intelligentsia and middle class and depended wholly on the masses for support and sustenance. This was the most-threatening movement the American Republic had ever had to face. (14)

Garveyism was a response to the racial fuel boiling in black people. This rage was in part the result of organized labor's unwillingness to deal with "the Negro problem" and of Jim Crow in the "golden North". Moreover Garveyism elevated black consciousness into realizing itself as independent. Garvey grounded with black people and told them of the imminent dangers of life in America - cultural rape, psychological instability, moral destruction. Garvey shouted "Up You Mighty Race!" because he foresaw the oppression strengthening its hand over black people. He was crushed: hounded, attacked, abused, accused of fraud. The US Government was instrumental in "ridding America of Garvey' while putting out the flames of revolution in Black America.

During this period organized labor was no-less oppressive. Craft unionism and its rise spread the gospel of the black workers' downfall. The AFL's unwritten exclusion policy was commented on by two black writers in 1931:

By refusing to accept apprentices from a class of workers that social tradition has stamped as inferior, or by withholding membership from reputable craftsmen of this class, the union accomplishes two things: It protects its "good" name, and it eliminates a whole class of future competitors. While race prejudice is a very-fundamental fact in the exclusion of the Negro, the desire to restrict competition so as to safeguard job monopoly and control wages is inextricably interwoven with it. (15)

The AFL refused to investigate and prohibit discrimination in its own internationals because it "would" create prejudice instead of breaking it down. (16) The CIO also was guilty of racism, but managed to escape this guilt because of the war-time expansion during its emergence and growth. (17) Following World War n, the black movement turned from institutional gains to "civil rights". It took Malcolm X and a host of other well-known black leaders to point out what so many black people had largely forgotten -that they are still oppressed, and that the only acceptable solution would be black-created and black-led.

The League responds to this oppression with a new and vital vigor, Black workers "entered industry on the lowest rung of the industrial ladder" (18), and that is where they remain. Organized labor has not contributed much to black labor, and the few exceptions like the IWW and the UMW have not been enough to offset the systematic exclusion and assault of black Iabor, The League knows this. It recognizes this fact of betrayal as a fossil. What follows is that something must be done, and the League is doing it. Sense the tone of the following, and remind yourself of history.

We fully understand, after five centuries under this fiendish system and the heinous savages that it serves, namely the white racist owners and operators of the means of destruction. We further understand that there have been previous attempts by our people in this country to throw off this degrading yoke of oppression, which have ended in failure. Throughout our history, black workers, first as slaves and later as pseudo freedmen, have been in the vanguard of potentially-successful revolutionary struggles in all black movements as well as in integrated efforts. As examples of these we cite: Toussaint L'Ouverture and the beautiful Haitian Revolution; the slave revolts led by Nat Turner, Denmark Vesey, Gabriel Prosser; the Populist movement and the labor movement of the Thirties in the US. Common to all these movements were two things: their failure and the reason why they failed. These movements failed because they were betrayed from within, or, in the case of the integrated movements, by white leadership exploiting the racist nature of the white workers they led. We, of course, must avoid that pitfall and purge our ranks of any traitors and lackeys that may succeed in penetrating this organization. At this point we loudly proclaim that we have learned our lesson from history and we shall not fail. So it is that we who are the hope of black people and all oppressed people everywhere dedicate ourselves to the cause of black liberation to build the world anew realizing that only a struggle led by black workers can triumph over our powerful reactionary enemy. (19)

The League's purpose is two-fold: to dissolve the bonds of white racist control, and thus, in turn, to relieve oppressed people the world over. It is fitting that the League's motto embodies the challenge: DARE TO STRUGGLE, DARE TO WIN!

As the reader goes through this issue and the important documents and analyses of black workers, I suggest that he remember the incisive comments of Karl Marx:

Men make their own history, but they do not make it as they please; they do not make it under circumstances chosen by themselves, but under circumstances directly encountered, given and transmitted from the past. The tradition of all the dead weighs like a nightmare on the brain of the living. (20)

Certainly there is no more-fitting way to begin our own self-criticism.

Footnotes

1. Abram L. Harris Junior: "The Negro and Economic Radicalism" in The Modern Quarterly,2, 3 (1924), Page 199.

2. To the Point of Production(Radical Education Project pamphlet, 1970), an interview with John Watson, Page 1.

3. Ibid., Page 3. The interested person might reflect on the import of this organizing shift. The League breaks with all black organization by emphasizing organizing at "the point of production". Community organizing represents a diversity of conflicting interests; for example the New York school conflict of 1968 centers on the antagonism of the black school board elite and conscious concerns of the black masses.

4. The ruling class had the power to integrate existing minorities. The existing minorities are powerless in decisions affecting such basic issues as housing, education, transportation, and employment. All the action by the integrationists takes place with the consent of the white ruling class. For a more-detailed discussion of this important ruling class tactic, the reader is urged to consult Robert L. Allen's important book Black Awakening in Capitalist America(Garden City, New York, 1969). The author was a Guardian correspondent during the birth of the Black Power age, and has some useful incisive analyses.

5. The myth of middle-class expansion has certainly taken its toll. More than 80% of Black America are engaged in some sort of service, industrial, or domestic employment or in the everyday struggle for survival because they are unemployed or underemployed. The "brother on the street", when considered within this framework, becomes not a lumpen proletarian, but an unemployed worker. Although there is a black lump en proletariat, it does not characterize the class reality of black people in America.

6. Booker T. Washington: "The Atlanta Exposition Address", quoted in Eric Perkins and John Higginson's "Black Students: Reformists or Revolutionaries?" in R. Aya and N. Miller: America: System and Revolution(New York, forthcoming). The reader should also consider the documents offered in Bracey, Meier, and Rudwick (editors): Black Nationalism in America(Indianapolis, 1970), relating to bourgeois nationalism and accommodation.

7. The Black Movement has been unable to regain much of the fuel it ignited during the lives of Martin Luther King Junior and Malcolm X. The leadership vacuum is widespread, resulting in a marked decline in struggle.

8. Ernie Mkalimoto: Revolutionary Nationalism and Class Struggle (Black star Publishing pamphlet, 1970). This pamphlet will soon be available in revised form. It is an extremely-important statement on black ideology, and should be possessed by all persons who consider themselves revolutionary. For more information write to Black star Publishing, 8824 Fenkell, Detroit, Michigan

9. Ibid. This is the most-important definition and refinement of the revolutionary-nationalist position to date.

10. Some fruitful analysis has already begun. Although the economics of racism is a sorely - neglected area, some people are beginning to realize its centrality. See the essay by Harold Baron in this issue and his forthcoming The Web of Urban Racism, and also the fresh analysis brought by economist William K. Tabb, The Political Economy of the Ghetto (New York, 1970).

11 Charles Kelsey: "The Evolution of Negro Labor", The Annals, 31 (1903), Page 57. This article is useful despite its Darwinist bias. The reader should also know of the two important studies conducted by W. E. B. Du Bois : The Negro Artisan and The Negro American Artisan, published in 1902 and 1912 respectively.

12. W. E. B. DuBois and associates: The Negro Artisan(Atlanta

University Press, 1902), Page 23.

13. The great race riots in East Saint Louis in 1917 and Chicago in 1919 underscored many other riots and rebellions. The causes of these events were the same as those of the great rebellions of July 1967 in Newark and Detroit - economic oppression coupled with the failure to meet rising expectations.

14. The work of a young Jamaican brother, Robert Hill, indicates that the Government felt itself threatened by the widespread success of the Garvey movement among the urban poor and unemployed. An essay of his on Garvey in America is soon due in an anthology on Garveyism edited by John H. Clarke. Any radical who refuses to acknowledge the stimulus of Garveyism will be forever learning about the Black Power movement.

15. Sterling D. Spero and Abraham L. Harris: The Black Worker (New York, Columbia University Press, 1931), Page 56.

16. statement of John P. Frey, molders chief, as quoted in Marc Karson and Ronald Radosh: "The AFL and the Negro Worker, 1894 to 1949", in Julius Jacobson (editor): The Negro and the American Labor Movement(New York, 1968), Page 170.

17. Sumner Rosen: "The CIO Era, 1935-1955", in Jacobson, Ope clt., Page 207. Also see Herbert R. Northrup: "Organized Labor and NegroWorkers", Journal of Political Economy, Number 206 (June 1943), and Organized Labor and the Negro(New York, 1944).

18. Lorenzo J. Greene and Carter G. Woodson: The Negro Wage Earner (Washington DC, 1930), Page 322.

19 :constitution of the Dodge Revolutionary Union Movement, 1968.

20. Karl Marx: The Eighteenth Brumaire of Louis Napoleon(New York, 1966), Page 15.

Comments

Old Spartacus League article on the former Detroit League of Revolutionary Black Workers.

Classic SL style!

"Soul Power or Workers Power? The Rise and Fall of the League of Revolutionary Black Workers"

http://www.marxists.org/history/erol/1960-1970/wv-lrbw.htm

While I wouldn't agree with SL vanguardism in the WV article, the overall article actually seems to make stronger and more substantial critique than any of the "non-aligned marxist" critiques that I have seen.

Marty Glaberman is well-respected here and his text

Having established itself with direct rank-and-file activity, DRUM decided to take advantage of an accidental vacancy on the local union executive board to run a candidate for that office (trustee). DRUM’s candidate, Ron March, made it clear that he was not following the usual course of union caucuses in attempting to get a share of the power. There was no pretence that a revolutionary black trustee would effect any change in the union.

http://www.marxists.org/archive/glaberman/1969/04/drum.htm

Which seems rather contradictory. DRUM ran for union office 'cause they knew it would make no difference?

Constituent articles:

- Introduction

- Marxism and Black radicalism in America (Naison, Mark)

- An interview with Aime Cesaire (Tomich, Dale)

- Poetry (Uhse, Stefan)

- Personal histories of the early C.I.O. (Lynd, Staughton)

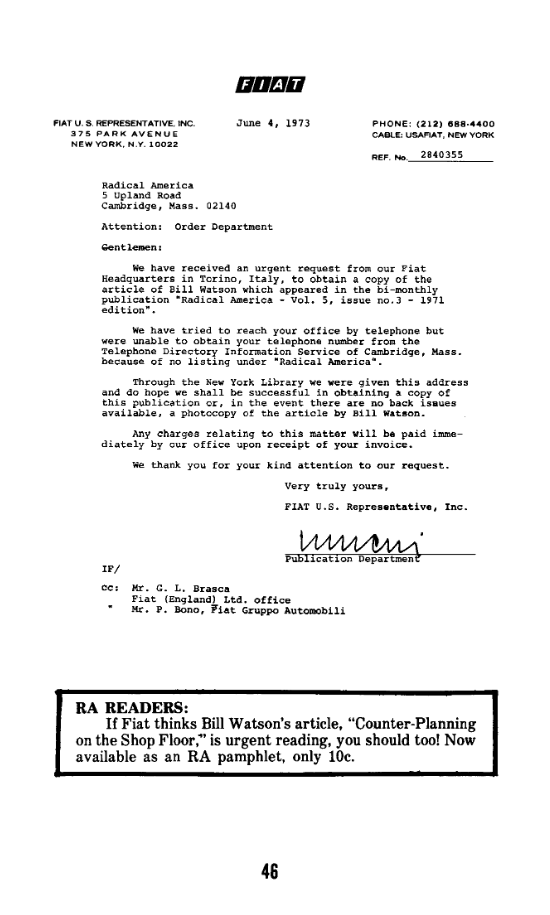

- Counter-planning on the shop floor (Watson, Bill)

- Reviews

Attachments

Comments

It is difficult to judge just when working-class practice at the point of production learned to bypass the union structure in dealing with its problems, and to substitute (in bits and pieces) a new organisational form. It was clear to me, with my year's stay in an auto motor plant (Detroit area, 1968), that the process had been long underway.

What I find crucial to understand is that while sabotage and other forms of independent workers' activity had existed before (certainly in the late nineteenth century and with the Wobbly period), that which exists today is unique in that it follows mass unionism and is a definite response to the obsolescence of that social form. The building of a new form of organization today by workers is the outcome of attempts, here and there, to seize control of various aspects of production. These forms are beyond unionism; they are only secondarily concerned with the process of negotiation, while unionism made that its central point.

Just as the CIO was created as a form of struggle by workers, so, out of necessity, that form is being bypassed and destroyed now, and a new organizational form is being developed in its place. The following, then, is by implication a discussion of the self-differentiation of workers from the form of their own former making. The activities and the new relationships which I record here are glimpses of a new social form we are yet to see full-blown, perhaps American workers' councils.(1)

Planning and counter-planning are terms which flow from actual examples. The most flagrant case in my experience involved the sabotaging of a six-cylinder model. The model, intended as a large, fast "6", was hastily planned by the company, without any interest in the life or the precision of the motor It ran rough with a very sloppy cam. The motor became an issue first with complaints emanating from the motor-test area along with dozens of suggestions for improving the motor and modifying its design (all ignored). From this level, activities eventually arose to counter-plan the production of the motor.

The interest in the motor had grown plant-wide. The general opinion among workers was that certain strategic modifications could be made in the assembly and that workers had suggestions which could well be utilized. This interest was flouted, and the contradictions of planning and producing poor quality, beginning as the stuff of jokes, eventually became a source of anger In several localities of the plant organized acts of sabotage began. They began as acts of mis-assembling or even omitting parts on a larger-than-normal scale so that many motors would not pass inspection. Organization involved various deals between inspection and several assembly areas with mixed feelings and motives among those involved-some determined, some revengeful, some just participating for the fun of it. With an air of excitement, the thing pushed on.

Temporary deals unfolded between inspection and assembly and between assembly and trim, each with planned sabotage. Such things were done as neglecting to weld unmachined spots on motor heads; leaving out gaskets to create a loss of compression; putting in bad or wrong-size spark plugs; leaving bolts loose in the motor assembly; or, for example, assembling the plug wires in the wrong firing order so that the motor appeared to be off balance during inspection. Rejected motors accumulated.

In inspection, the systematic cracking of oil-filter pins, rocker-arm covers, or distributor caps with a blow from a timing wrench allowed the rejection of motors in cases in which no defect had been built in earlier along the line. In some cases, motors were simply rejected for their rough running.

There was a general atmosphere of hassling and arguing for several weeks as foremen and workers haggled over particular motors. The situation was tense, with no admission of sabotage by workers and a cautious fear of escalating it among management personnel. Varying in degrees of intensity, these conflicts continued for several months. In the weeks just preceding a change-over period, a struggle against the V-8s (which will be discussed later) combined with the campaign against the "6s" to create a shortage of motors. At the same time management's headaches were increased by the absolute ultimate in auto-plant disasters - the discovery of a barrage of motors that had to be painstakingly removed from their bodies so that defects that had slipped through could be repaired.

Workers returning from a six-week change-over layoff discovered an interesting outcome of the previous conflict. The entire six-cylinder assembly and inspection operation had been moved away from the V-8s - undoubtedly at great cost to an area at the other end of the plant where new workers were brought in to man it. In the most dramatic way, the necessity of taking the product out of the hands of laborers who insisted on planning the product became overwhelming. There was hardly a doubt in the minds of the men in a plant teeming with discussion about the move for days that the act had countered their activities. A parallel situation arose in the weeks just preceding that year's changeover, when the company attempted to build the last V-8s using parts which had been rejected during the year The hope of management was that the foundry could close early and that there would be minimal waste. The fact, however, was that the motors were running extremely rough; the crankshafts were particularly shoddy; and the pistons had been formerly rejected, mostly because of omitted oil holes or rough surfaces.

The first protest came from the motor-test area, where the motors were being rejected. It was quickly checked, however, by management, which sent down personnel to hound the inspectors and to insist on the acceptance of the motors. It was after this that a series of contacts, initiated by motor-test men, took place between areas during breaks and lunch periods. Planning at these innumerable meetings ultimately led to plant-wide sabotage of the V-8s. As with the six-cylinder motor sabotage, the V-8s were defectively assembled or damaged en route so that they would be rejected. In addition to that, the inspectors agreed to reject something like three out of every four or five motors.

The result was stacks upon stacks of motors awaiting repair, piled up and down the aisles of the plant. This continued at an accelerating pace up to a night when the plant was forced to shut down, losing more than 10 hours of production time. At that point there were so many defective motors piled around the plant that it was almost impossible to move from one area to another.

The work force was sent home in this unusually climactic shutdown, while the inspectors were summoned to the head supervisor's office, where a long interrogation began. Without any confession of foul play from the men, the supervisor was forced into a tortuous display which obviously troubled even his senses, trying to tell the men they should not reject motors which were clearly of poor quality without actually being able to say that. With tongue in cheek, the inspectors thwarted his attempts by asserting again and again that their interests were as one with the company 5 in getting out the best possible product. In both the case of the "6s" and the V-8s, there was an organized struggle for control over the planning of the product of labor; its manifestation through sabotage was only secondarily important. A distinct feature of this struggle is that its focus is not on negotiating a higher price at which wage labour is to be bought, but rather on making the working day more palatable. The use of sabotage in the instances cited above is a means of reaching out for control over one's own work. In the following we can see it extended as a means of controlling one's working "time."

The shutdown is radically different from the strike; its focus is on the actual working day. It is not, as popularly thought, a rare conflict. It is a regular occurrence, and, depending on the time of year, even an hourly occurrence. The time lost from these shutdowns poses a real threat to capital through both increased costs and loss of output. Most of these shutdowns are the result of planned sabotage by workers in certain areas, and often of plantwide organization.

The shutdown is nothing more than a device for controlling the rationalization of time by curtailing overtime planned by management. It is a regular device in the hot summer months. Sabotage is also exerted to shut down the process to gain extra time before lunch and, in some areas, to lengthen group breaks or allow friends to break at the same time. In the especially hot months of June and July, when the temperature rises to 115 degrees in the plant and remains there for hours, such sabotage is used to gain free time to sit with friends in front of a fan or simply away from the machinery.

A plantwide rotating sabotage program was planned in the summer to gain free time. At one meeting workers counted off numbers from ~ to 50 or more. Reportedly similar meetings took place in other areas. Each man took a period of about 20 minutes during the next two weeks, and when his period arrived he did something to sabotage the production process in his area, hopefully shutting down the entire line. No sooner would the management wheel in a crew to repair or correct the problem area than it would go off in another key area. Thus the entire plant usually sat out anywhere from 5 to 20 minutes of each hour for a number of weeks due to either a stopped line or a line passing by with no units on it. The techniques for this sabotage are many and varied, going well beyond my understanding in most areas.

The "sabotage of the rationalization of time" is not some foolery of men. In its own context it appears as nothing more than the forcing of more free time into existence; any worker would tell you as much. Yet as an activity which counteracts capital's prerogative of ordering labour's time, it is a profound organized effort by labor to undermine its own existence as "abstract labour power" The seizing of quantities of time for getting together with friends and the amusement of activities ranging from card games to reading or walking around the plant to see what other areas are doing is an important achievement for laborers. Not only does it demonstrate the feeling that much of the time should be organized by the workers themselves, but it also demonstrates an existing animosity toward the practice of constantly postponing all of one's desires and inclinations so the rational process of production can go on uninterrupted. The frequency of planned shutdowns in production increases as more opposition exists toward such rationalization of the workers' time.

What stands out in all this is the level of cooperative organization of workers in and between areas. While this organization is a reaction to the need for common action in getting the work done, relationships like these also function to carry out sabotage, to make collections, or even to organize games and contests which serve to turn the working day into an enjoyable event. Such was the case in the motor-test area.

The inspectors organized a rod-blowing contest which required the posting of lookouts at the entrances to the shop area and the making of deals with assembly, for example, to neglect the torquing of bolts on rods for a random number of motors so that there would be loose rods. When an inspector stepped up to a motor and felt the telltale knock in the water-pump wheel, he would scream out to clear the shop, the men abandoning their work and running behind boxes and benches. Then he would arc himself away from the stand and ram the throttle up to first 4,000 and then 5,000 rpm. The motor would knock, clank, and finally blur to a cracking halt with the rod blowing through the side of the oil pan and across the shop. The men would rise up from their cover, exploding with cheers, and another point would be chalked on the wall for that inspector This particular contest went on for several weeks, resulting in more than 150 blown motors. No small amount of money was exchanged in bets over the contests.