Online home of Aufheben, a UK-based libertarian communist journal founded in 1992.

The journal Aufheben was first produced in the UK in Autumn 1992. Those involved had participated in a number of struggles together - the anti-poll tax movement, the campaign against the Gulf War - and wanted to develop theory in order to participate more effectively: to understand capital and ourselves as part of the proletariat so we could attack capital more effectively. We began this task with a reading group dedicated to Marx's Capital and Grundrisse. Our influences included the Italian autonomia movement of 1969-77, the situationists, and others who took Marx's work as a basic starting point and used it to develop the communist project beyond the anti-proletarian dogmatisms of Leninism (in all its varieties) and to reflect the current state of the class struggle. We also recognized the moment of truth in versions of class struggle anarchism, the German and Italian lefts and other tendencies. In developing proletarian theory we needed to go beyond all these past movements at the same time as we developed them - just as they had done with previous revolutionary movements.

Aufheben comes out once a year (see subscription details), and to date (April 2011) there have been nineteen issues. This site contains all of the articles from previous issues and also some pamphlets. Since Aufheben is a developing project, some of our own ideas have already been superseded. We do not produce these ideas in the abstract, but, as we hope comes across in these articles, are involved in many of the struggles we write about, and develop our perspective through this experience.

Latest issue

Issues

Commentaries

Pamphlets & Articles

Purchase and subscription details

Back issues

Myspace

Facebook

Aufheben - Greatest Hits

Attachments

Aufheben 24 (2017)

AVAILABLE NOW

Contents:

BREXIT MEANS… WHAT?

HAPLESS IDEOLOGY AND PRACTICAL CONSEQUENCES

A number of left groups and individuals campaigned for the UK to leave the European Union in the recent referendum. We argue that the Brexit campaign, and the referendum itself, its results and its implementation, have been one with a victory of the ruling class against us. The implementation of Brexit will negatively affect solidarity among workers and radical protesters, setting back our strength and potentials to overturn capitalism. Many people in the radical left were blinded by the ideological forms of our capitalist relations, the reification of our human interactions, to the point of accepting a victory of the far right with acquiescence, or even collaborating with it.

THE RISE OF CONSPIRACY THEORIES:

REIFICATION OF DEFEAT AS THE BASIS OF EXPLANATION

Conspiracy theories have become more widespread in recent years. As populist explanations, they offer themselves as radical analyses of ‘the powerful’ – i.e., the operation of capital and its political expressions. One of the features that is interesting about such conspiracy theories therefore is that they reflect a critical impulse. We suggest that at least part of the reason for their upsurge (both in the past and in recent years) has to do with social conditions in which movements reflecting class struggles have declined or are seen to be defeated. We trace the rise of conspiracy theories historically and then focus on the most widespread such theory today – the idea that 9/11 was an inside job. We suggest that one factor in the sudden rise of 9/11 conspiracy theories was the failure and decline of the movement against the war in Iraq.

CHINA: THE PERILS OF BORROWING SOMEONE ELSE’S SPECTACLES

We argue that the transition facing China is the shift from the export of commodities to export of capital. This transition would mark a major step in transforming China from what we have termed a mere epicentre in the global economy to its establishment as a distinct second pole of within the global accumulation capital – an emerging antipode to that of the US. The group Chuǎng argue that recent Aufheben analyses are ‘too optimistic’ concerning China’s ability to maintain economic growth rates and fuel global capital accumulation. We reproduce their article as an Intake. In our response, we contend Chuǎng are unable even to recognise what we are suggesting let alone argue against it. This is because in making their analysis of the current economic situation in China, they have borrowed the spectacles of neo-liberal economics. They have thereby inadvertently adopted a myopic and ideologically circumscribed perspective that contains crucial blind-spots.

£4.00 (UK) and £6 (elsewhere), including postage - see our subscription and contact details to order a copy, or buy through Paypal below.

Comments

Spanish Translation of issue #19:

http://klinamen.org/noticias/aufheben-19

Our class demands the immediate publication of this article as a PDF file:

INTAKES: COMMUNITIES, COMMODITIES AND CLASS IN THE AUGUST 2011 RIOTS

Is the next issue (#21) going to be published this year? If so then when approximately?

Aren't these the same people who not so long ago were arguing that capitalism was on the verge of a "new upswing"?

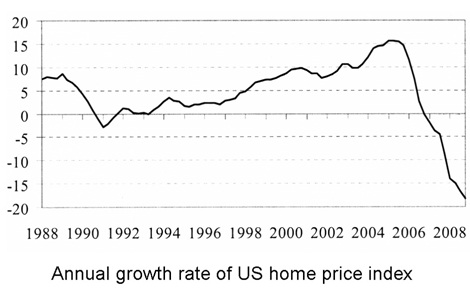

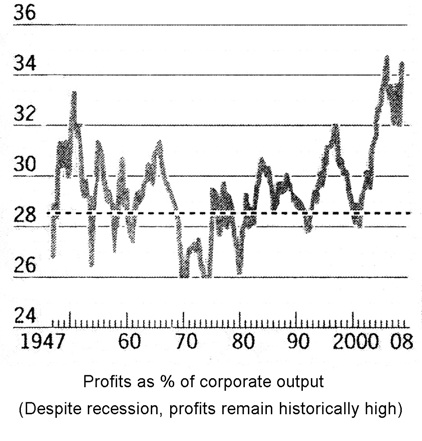

In the conclusion to the crisis article in a previous issue, we did suggest - although tentatively - that the financial crisis might not mark the beginning of a long downswing in capital accumulation mainly on the basis of the rapid recovery in the rate of profit that has followed the crisis. We also suggested - although admittedly in footnote - that the crisis may have been the first tremor due to the tectonic shifts in global capitalism brought about by the rise of China and the 'emerging global south'.

So were we wrong? Yes and no.

Certainly for those of us in the old capitalist heartlands the last five years have been an unprecedented period of economic stagnation. For North America, Japan and much of Europe - with the notable exception of Germany and its hinterland in North and East of Europe (see our article on the euro-crisis in issue 21) - the economic recovery has been weak if not non-existent. However, this has not been the case for China and the 'emerging economies of the global south' that rapidly bounced back from the crisis of 2008. Up until the last year or so China has been growing at over 10% a year. Whereas much of the old capitalist heartlands have barely recovered pre-crisis levels of output, China's GDP is more than 50% bigger. During this time it has overtaken Japan to become the second largest economy in the world. This rapid capital accumulation in China has pulled the emerging economies behind it.

Before the crisis, the global economy was growing at between 4%-5% a year - quite a brisk pace by historical standards. In the period after the crisis the world economy has been growing at 3%-4% mainly due to China centred capital accumulation. A significant slowdown, but hardly economic stagnation. This can be seen as part of the shift in the centre of global capital accumulation towards China and the emerging global south - the moving of the tectonic plates.

Now it is true that this post-crisis period seems to be coming to end. China's economic growth has been slowed down to around 7% and this is having an impact on the emerging economies of the global south as evident in the current crisis in India that may well trigger another global financial crisis. At the same time US economic recovery seems to be gathering pace at last.

Now we must admit that we did not predict this tale of two worlds of the past five years. We underestimated China’s economic development and hence its relative autonomy from capital accumulation in the USA. We also failed to foresee the stagnation in the West.

In the article in this year’s issue, we look at the failure of the economic recovery in the West – focusing on the example of the UK. We look at how far this failure was due to what can be considered as contingent factors such as the policy response of the government and how far it was due to deeper structural factors such as the rise of China.

Actually, I don't think you said:

we did suggest - although tentatively - that the financial crisis might not mark the beginning of a long downswing in capital accumulation mainly on the basis of the rapid recovery in the rate of profit that has followed the crisis.

at the time. I think you said that capital was poised on the verge of a new long-term upswing. Something like that.

I think your analysis then, as your analysis now, is, to put it mildly-- superficial.

How did and how is the rest of the world, outside of the West, doing these days? Just got and started reading the new issue today. Is this thread heading into another round debating up or down-swings, China's looming dominance, etc..?

In the upcoming #9 of our publication, Cuadernos de Negación (http://cuadernosdenegacion.blogspot.com.ar/), and in the #10 and #11 also, we'll be developing a critique of the economy. In #9 there is a section called "Myths of the economist" that tries to show why such concepts as interest, barter, robinsonadas (as the spansh translation of marx called it), economicist essence and the uniqueness and universality of value, are historical constructions of the dominant class and nothing else. And by utilizing these myths, the dominant ideology forces on us a very particular and historically specific view of world.

In that section we have used some quotations from David Graeber's book. We have enjoyed Graeber's book but we're aware of the deviations that both the author and the book have. We have read some criticism, both in spanish and in english, to the book, but we believe, as we are big fans since we've first read aufheben six or seven years ago, that this one will be of qualitative importance.

So, we are asking if you can send us this particular text via mail at (cuadernosdenegacion at hotmail dot com) because it would be very good to discuss your positions here with our comrades. The new issue of our publication will be issued in 1-2 months so the timing will be important here. It would be very good to read your article and include some of your thoughts here (by reading many of your texts we're trusting more in more in your analysis and when we learn that an issue is close we anxiously expect it).

So, in case the pdf is not available soon, please send us that particular text via mail so we can enjoy and include your positions in our publication. We don't have paypal or credit card and with the change of currency and the low salaries here, the 15 pounds for the 3 issues transform to about 1/10 of our monthly wage. We're sure you'll understand this.

Thanks in advance and congratulations for the ongoing effort.

Cuadernos.

We now anticipate going to press some time in January.

We will have articles on Obama's pivot from the Middle East to China, workers' experience and enquiry, and disaster communism.

Aufheben, October 2014

I haven't heard anything, assume it's not out yet. The unemployed centre is getting evicted in a couple of weeks by the Trot bosses who stole half a million quid from it. Should do something for news on that actually.

We are hoping to publish in the next month or so. Most of the stuff is written. We are still finding most of our time caught up in the struggle to keep the unemployed centre open - this is the reason for the delay still. More here:http://www.boycottworkfare.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/11/Save-the-centre_3-November-2014.pdf

At about 6pm October 6th 2015 UK time this was no.4 on the list of "recent posts"; scroll down and you see the last post is Feb 28 23.30. Clearly someone posted to this page and did not realise that almost everything referring to Aufheben in a critical way is automatically censored by libcomatose without any admission that it has been. This has happened several times. This post will obviously be censored too....Rocking the boat is forbidden, even when it is The Titanic.........

Or it might have been that the newest edition has been added to the files, the one just published, the one the picture up top references, thus updating the thread, cunningly alluded to when the little red letters nest the thread said "updated." Bloody hell, makes you think....

The word "updated" in "little red letters" must have been written so little that to my eyes they are as invisible as the credibility of this site.

right. it says "new" in red, the sly bastards. And then that graphic, showing an issue with the date 2015-2016.... censors at work, no doubt.

I mean, censors might be at work, but that's hardly the evidence, is it? Unless the work includes long snoozes, periods of inattention, and general slackness.... hey, can I get that gig?

And then there is that whole exchange about issue 23, scheduled to appear in October 2014. So... only a year late. Hell, with a schedule like that Aufheben could be Insurgent Notes.

It's awful cover art, by the way. Why are there ducks swimming on the bottom half of the bisected ballerina? Or is she half woman, half mushroom?

GerryK

At about 6pm October 6th 2015 UK time this was no.4 on the list of "recent posts"; scroll down and you see the last post is Feb 28 23.30. Clearly someone posted to this page and did not realise that almost everything referring to Aufheben in a critical way is automatically censored by libcomatose without any admission that it has been. This has happened several times. This post will obviously be censored too....Rocking the boat is forbidden, even when it is The Titanic.........

lolz. As others have pointed out your conspiraloon theory is a bit off. This post was updated because the new issue has changed. This is a screenshot of the admin panel:

As you will be well aware, we were the ones who published the initial critiques of Aufheben, and we continue to host those articles as well as forum discussions containing probably hundreds of posts of people criticising Aufheben.

What we do have, however, are rules against derailing, off topic posts and comments which belong on other threads. As you are well aware, as it is the only thing you ever talk about, there are many other threads and posts on libcom where you can talk about this subject. So if you really want to keep going on about it you are welcome to do so there. However we will not have you derailing any other threads. This is a final warning, as it has been years and you keep doing it.

Some of the derailing comments have been unpublished. However I'm going to leave yours and this here until you have had time to see it, then they will be unpublished, as will this.

PS "libcomatose" that's a pretty poor effort. Seriously you have had a few years now I would have thought you could have come up with something better than that… What does it even mean?

Last night I replied to Khawaga's blatant flaming - and the reply has been deleted (even though there was no flaming in it whatsoever). Now Steven, playing the typical manipulative role he invariably plays, totally falsifies the history of Johnny and Aufheben and libcom and my posts and even this thread in every detail. But I shall not waste time any further on this complacent mutual congratulation society (sighs of relief all round).

Not flaming, Gerry K. I only posted facts. And in light of you last post, I think my comment was warranted. Really, for all the fucking very correct critiques you have of Dr. Crowd control, the way you go about it, making it out to be some massive conspiracy theory makes you look like a fucking idiot.

I might well have been wrong about the particular case of censorship here (though none of the red "new" or "updated" words appear on my version of this webpage) but

you're a fucking idiot.

if you think that critiquing the gang-like obsessional censorship mentality of libcoma admin (see , for instance the way Steven reacted to some comments - now disappeared, in reaction to the libcom sycophant Rob Ray's comments on the Michael Schmidt thread) amounts to

some massive conspiracy theory

. Here you reproduce the dominant societys very convenient dismissal of any recognition of the commonality of interest amongst the ruling class as the mentality of "conspiracy nutters" on the small scale of a critique of the libcoma gang.

The problem with professional intellectuals like you (however proletarianised you might well be) is that you are so stuck in your heads as to be incapable of recognising anger, let alone making decisions, as an essential contribution to subverting your own complacency towards this society and to those like libcoma who are complicit with it. For you it is enough to have a merely "theoretical " critique divorced from emotions or genuine attack.

Really

(though none of the red "new" or "updated" words appear on my version of this webpage)

No, it doesn't after you've clicked on it the first time. It's no longer new or a version which has been updated once you've looked at it. If it doesn't show up at all on any of threads, then it's something to do with the browser you're using.

The problem with professional intellectuals like you (however proletarianised you might well be) is that you are so stuck in your heads as to be incapable of recognising anger, let alone making decisions, as an essential contribution to subverting your own complacency towards this society and to those like libcoma who are complicit with it. For you it is enough to have a merely "theoretical " critique divorced from emotions or genuine attack.

Damn, what app are you using to detect my emotional states? And that I am apparently complacent towards society. And not just now, apparently over several years even. Or do you have some inhuman superpower? That's really impressive!

What I think is just too precious for words, and says all that needs to be said is that we can all talk about censorship and conspiracies , but nobody apparently has the time to comment on this kind of crap:

OBAMA’S PIVOT TO CHINA

In this article we consider the unfolding of civil war following the demise of the Arab Spring and then place this complex conflict in the context of the overarching imperatives of US foreign policy. As we shall argue, contrary to the common view on the left and in the anti-war movement, far from being hell bent on war against Syria and Iran, the Obama administrations approach to the Syrian conflict has been determined by the ultimate aims of establishing a rapprochement with Iran in order to secure stability in the Middle East, permit the opening up of the Iranian and Iraqi oil and allow for a major shift in emphasis of US foreign policy towards the rise of China and Asia.

Yeah right, that's the ticket. Sorry, it doesn't matter what capitalism wants-- rapprochement with this or that regime-- "stability" is simply out of the question. And that stuff about "opening up of Iranian an Iraqi oil...." excuse me, as Ripley said, "did IQs drop sharply while I was away?" Anybody paying attention to the overproduction in the oil industry? That US production although down a bit is at its second highest level in what? 35 years? 40 years? That Russia is pumping at a rate last seen before the fSU collapsed? That the Saudis have ramped up production above 10 million b.o.e/day? That the US had every opportunity to "open up" Iraqi oil when it governed, if you can call it that, Iraq, and when it came time to bid on the leases and licenses, the US oil companies quite simply had almost zero interest?

The pivot to confront China? No one it would ever guess it has anything to do with overproduction, right? That it has anything to do with slowing growth in world trade, and all those other things that run counter to the so-called "inflection point" for a new capitalist upsurge?

It's mildly amusing that I tick you off so much you feel it necessary to slate me on threads I've nothing to do with Gerry, though I'm sorry to say I can't reciprocate your obsession as you're entirely uninteresting. Tbh usually whenever I see you've involved yourself in some thread or other it just makes me feel a bit libcomatose.

I wrote:

the libcom sycophant Rob Ray's comments on the Michael Schmidt thread

Rob Ray wrote:

you feel it necessary to slate me on threads I've nothing to do with

So these have nothing to do with Rob Ray:

http://libcom.org/forums/general/ak-press-says-michael-schmidt-fascist-25092015?page=2#comment-565915

In which case there are at least 2 possiblities:

1. Someone has hacked into Rob Rays libcom account.

2. Rob Ray is indeed in such a libcoma he does not know what he said or where.

Rob Ray will undoubtedly find some Third Position unless his declared lack of interest .in anything I say prevents him from responding this time.

And, yes, S.Artesian has shown that even in the safe sphere of an analysis of objective developments in political economy in which it has hoped to display its specialism, Aufheben has shown itself to be devoid of the slightest intelligence.

GerryK

The word "updated" in "little red letters" must have been written so little that to my eyes they are as invisible as the credibility of this site.

Not trying to be smarmy, s. Artesian but are you suggesting that military action in Midwest is to slow production of oil? Just trying to make sure I understand your criticism. I've heard other people say similar things that it's about CONTROLLING production of oil not simply "getting it."

Of course we have to disentangle the general systemic or total trends from those particular struggles which drive the total trends, in some ways right?

I think that the cause of the invasion of Iraq was the decline in oil prices, first in 1998, brought about by overproduction, and then again in 2002.

The war in the Mideast drove the price of oil to spectacular, in every sense of the word, highs and with that price change, massive profits were siphoned into the industry. There followed, as there always follows the implosion. However, over the long term, this brought the rate of profit in the industry more in line with that of the average rate of profit, whereas before, in the period 1986-1991 (until the first invasion of Iraq) and then again from 1997-1999 rates of profit in the industry were generally lower than average, which makes sense given the enormous concentration of "dead value" accumulated in the means of production.

So yeah, the US "oil men" were quite vociferous, and specific, in complaining about Iraqi production which had reach 3 million barrels/day. Bush and Cheney did exactly what they were paid to do.

Petey: now that you've provided me with glasses I can see the sense of Aufheben - TOZ3LPED4PECFD5EDFCZP6.

And yes Chilli Sauce, man, everything on libcom, man, has been getting sad for a long long time, man, and it is sad that there are still a few intelligent people, man, who think it worth contributing to this sad site for sore eyes, man (an example of sadness is Rob Ray who complains that I slate him on threads he has nothing to do with and yet does the very same thing on the Michael Schmidt thread - slating someone, in a totally spurious manner, who not only had nothing to do with with that thread but has had nothing to do with libcom for years). And - yes - it is sad for me to bother to go on writing this kind of stuff. Consequently I shall never write anything on libcom ever again and you can go back to being happy.

Good points S. Artesian, any book recommendations or is this from following the press through the period?

Oh I'm not complaining Gerry, as I say I found it mildly amusing that you're clearly so upset by me when I have so little interest in you. As for mentioning Samotnaf, that was a contextual aside based on saying I didn't think the Schmidt thing came from the same place as a similar sort of event in libcom's past - direct comparison, as opposed to unrelated whinge.

Having said this, I can see you trying to slide the thread back onto your favourite topic, you naughty old goat, so I think I'll stop the derailing here. Have a lovely time throwing your endless tantrums ;).

Mostly from following the press, and the stats from the US Energy Information Agency, which used to produce a great "Appendix B" to their annual reports-- called Financial Performance-- but dropped it when the Congress cut all the money (among other things, those cuts eliminated the Dept. of Commerce's Annual Statistical Abstract. Now, I believe the data is farmed out to some private group that publishes something almost, but not quite official, and I think for 2 or 3 times what the US GPO used to charge).

For books, I recommend Cyris Bina The Economics of the Oil Crisis, and Gorelick's Oil Panic and Global Crisis

S. Artesian

For books, I recommend Cyris Bina The Economics of the Oil Crisis

Great book and excellent recommendation. But his given name is Cyrus.

Could you suggest any book about the coal industry?

Right. My misspelling. Thanks.

Actually, I haven't read anything about the coal industry in years. My bad. Not even about the Powder River Basin, which was the "great coming thing" back when I first hired out on the railroad in 1972.

Hey Hieronymous,

Given that some trolls have an axe to grind, every time someone down votes your posts, I will up vote them. Even, and particularly, when, the post is disagreeing with me. It's the very least I can do to counter the facebook-ization of Libcom.

S. Artesian

Hey Hieronymous,

Given that some trolls have an axe to grind, every time someone down votes your posts, I will up vote them. Even, and particularly, when, the post is disagreeing with me. It's the very least I can do to counter the facebook-ization of Libcom.

Thanks comrade.

S. Artesian

Right. My misspelling. Thanks.

Actually, I haven't read anything about the coal industry in years. My bad. Not even about the Powder River Basin, which was the "great coming thing" back when I first hired out on the railroad in 1972.

But... I will note, that as of last month, there is no longer a single unionized coal mine in Kentucky (I think).

S. Artesian

S. Artesian

Right. My misspelling. Thanks.

Actually, I haven't read anything about the coal industry in years. My bad. Not even about the Powder River Basin, which was the "great coming thing" back when I first hired out on the railroad in 1972.

But... I will note, that as of last month, there is no longer a single unionized coal mine in Kentucky (I think).

You're right. Here's the story I saw about it last month: "No union mines left in Kentucky, where labor wars once raged."

A brief introduction to the Aufheben group and magazine.

Aufheben: (past tense: hob auf; past participle: aufgehoben; noun: Aufhebung)

There is no adequate English equivalent to the German word Aufheben. In German it can mean "to pick up", "to raise", "to keep", "to preserve", but also "to end", "to abolish", "to annul". Hegel exploited this duality of meaning to describe the dialectical process whereby a higher form of thought or being supersedes a lower form, while at the same time "preserving" its "moments of truth". The proletariat's revolutionary negation of capitalism, communism, is an instance of this dialectical movement of supersession, as is the theoretical expression of this movement in the method of critique developed by Marx.

The journal Aufheben was first produced in the UK in Autumn 1992. Those involved had participated in a number of struggles together - the anti-poll tax movement, the campaign against the Gulf War - and wanted to develop theory in order to participate more effectively: to understand capital and ourselves as part of the proletariat so we could attack capital more effectively. We began this task with a reading group dedicated to Marx's Capital and Grundrisse. Our influences included the Italian autonomia movement of 1969-77, the situationists, and others who took Marx's work as a basic starting point and used it to develop the communist project beyond the anti-proletarian dogmatisms of Leninism (in all its varieties) and to reflect the current state of the class struggle. We also recognized the moment of truth in versions of class struggle anarchism, the German and Italian lefts and other tendencies. In developing proletarian theory we needed to go beyond all these past movements at the same time as we developed them - just as they had done with previous revolutionary movements.

Aufheben comes out once a year (see subscription details), and to date (September 2006) there have been fourteen issues. This site contains all of the articles from these fourteen issues and also some pamphlets. Since Aufheben is a developing project, some of our own ideas have already been superseded. We do not produce these ideas in the abstract, but, as we hope comes across in these articles, are involved in many of the struggles we write about, and develop our perspective through this experience.

This page contains the editorial from the first issue (Autumn 1992), which expands on some of these points.

Editorial

"Theoretical criticism and practical overthrow are ... inseparable activities, not in any abstract sense but as a concrete and real alteration of the concrete and real world of bourgeois society." (Karl Korsch.)

We are living in troubled and confusing times. The Bourgeois triumphalism that followed the collapse of Eastern Bloc has given way to fear and incomprehension at the return of war, nationalism and fascism to Europe. The tumultuous events of the last four years have shattered the certainties of the Cold War period. Yet for all the momentous changes that have followed on from the collapse of the Eastern Bloc, it would seem that, after more than thirteen years of Thatcherism and designer socialism, that the prospect of revolutionary change is more remote than ever. Indeed in the Cold War period the very petrified state of geo-politics actually allowed the projection of total social revolution - a real leap beyond capitalism in its Eastern and Western varieties - as the only possibility beyond the status quo. Now, however, we see the real dangers of fundamental changes and ruptures within the parameters of continuing capitalist development. Within these dangers there does lie the real possibility of the further development of the social revolutionary project. But to recognise and seize the opportunities the changing situation offers we need to arm ourselves theoretically and practically. The theoretical side of this requires a preservation and superseding of the revolutionary theory that has preceded us.

Capitalism creates its own negation in the proletariat, but the success of the proletariat in abolishing itself and capital requires theory. At the time of the first world war the theory and praxis of the classical workers' movement came close to smashing the capital relation. But it was defeated by capital using both Stalinism and social democracy. The domination of the workers movement by Stalinism and social democracy that followed was an expression of this defeat of both the theory and practice of the proletariat.

The first stirrings from the long slumber began in the fifties following the death of Stalin and with the revolts against Stalinism by East German and Hungarian workers. This rediscovery of autonomous practice by the proletariat was accompanied by a rediscovery of the high points of the theory of the classical workers movement. In particular the German and Italian left communist critiques of the Soviet Marxism, the seminal work of Lukacs and Korsch in the critique of the objectivism of Second International Marxism which Leninism has failed to go beyond.

The New Left that emerged from this process was in a sense the reemergence of a whole series of theoretical currents - council communism, class struggle and liberal versions of anarchism, Trotskyism - that had largely been submerged by Stalinism. But while a number of groups that sprung up to a large extent just regurgitated as ideology the theories they were discovering, there were some real attempts to go beyond these positions, to actually develop theory adequate to the modern conditions. The period is marked by an explosion of new ideas and possibilities. The situationists and the autonomists represent high points in this process of reflecting and expressing the needs of the movement.

The rediscovery of the proletariat's theory happened in a symbiotic relation with the rediscovery of proletarian revolutionary practice. The wildcat strikes and general refusal of work, the near revolution in France in '68, the 'counter cultural' creation of new needs by the proletariat, in total a successful attack on the Keynesian settlement that had maintained social peace since the war. But with capital's successful use of crisis to undermine the gains of the proletarian offensive began a crisis in the ideas of the movement. The crisis was a result of the attacks on practice. We can see a number of directions in the collapse of the New Left.

One was a reformist turn: Under the mistaken notion that they were taking the struggles further - marching through the institutions - many comrades entered the Western social democratic parties. This move did not act to unify and organise the mass movements and grassroots struggles but rather encouraged and covered up the decline of these social movements. Those who avoided the mistake of being incorporated into the system fell into twin errors. On the one hand many embroiled themselves in frantic party-building. They were persuaded that the problem with the movement so far was the lack of an organisation to attack capital and the state. While they built their party the movementwas breaking up. They were blind to the history of Trotskyism as the 'loyal opposition' to Stalinism.

On the other hand many of those who recognised the bankruptcy of Leninism fell into a libertarian swamp of lifestylism and total absorption in 'identity politics' etc. Meanwhile from Academia came a sophisticated attack on radical theory in the guise of radical theory. The libertarian critique of Leninism - that it is an attempt to replace one set of rulers with another set - was transformed into an attack on the very project of social revolution. While appearing in their discourse to be exceptionally radical, the political implications of the postmodernists and poststructuralists amount to at best a wet liberalism, while at worst a justification for nationalism and wars.

The collapse of the new left parallelled the retreat of the proletariat as a whole before the onslaught of capitalist restructuring. In Britain we had the debilitating affect of the 'social contract' under Labour and the exceptionally important defeat of the miners strike. Elsewhere the crushing of the Italian movement and so on.

This brings us to the present situation. The connection between the movement and ideas has been undermined. Theory and practice are split. Those who think do not act, and those who act do not think. In the universities where student struggles forced the opening of space for radical thought that space is under attack. The few decent academic Marxists are besieged in their ivory tower by the poststructuralist shock troops of neo-liberalism. Although decent work has been done in areas such as the state derivation debate there has been no real attempt apply any insights in the real world. Meanwhile out in the woods of practical politics, though we have had some notable victories recently, ideas are lacking. Many comrades, especially in Britain, are afflicted with a virulent anti-intellectualism that creates the ludicrous impression that the Trots are the ones with a grasp of theory. Others pass off conspiracy theories as a substitute for serious analysis.

We publish this journal as a contribution to the reuniting of theory and practice. Aufheben is a space for critical investigation which has the practical purpose of overthrowing capitalist society.

Aufheben editorial group would like to receive articles from contributors for our 'Intake' pages. Whilst we would not publish something with which we substantively disagreed, we would try to find a way to include material with which we did not agree fully should it raise issues which we consider important to debate. We would also appreciate letters. A letters page can serve as a valuable forum for debate, and would go some way towards breaking down the division between writers and readers. Artwork would also be gratefully received.

Aufheben can be obtained by subscription. It would be of great help to us if as many readers as possible subscribed. This would not only provide valuable financial resources in advance of printing, but would also reduce the amount lost as profit to the bookshops.

Comments

"There is no adequate English equivalent to the German word Aufheben. In German it can mean "to pick up", "to raise", "to keep", "to preserve", but also "to end", "to abolish", "to annul".

Now my Deutsch is very basic but wouldn't this duel meaning make the word liberation an effective substitution? To truly Liberate means to raise up the downtrodden and preserve their existence, and it does this by abolishing the forces that suppress the newly picked up.

Just a thought.

Aufheben #1 Editorial: "Theoretical criticism and practical overthrow are ... inseparable activities, not in any abstract sense but as a concrete and real alteration of the concrete and real world of bourgeois society." (Karl Korsch.)

We are living in troubled and confusing times. The Bourgeois triumphalism that followed the collapse of Eastern Bloc has given way to fear and incomprehension at the return of war, nationalism and fascism to Europe. The tumultuous events of the last four years have shattered the certainties of the Cold War period. Yet for all the momentous changes that have followed on from the collapse of the Eastern Bloc, it would seem that, after more than thirteen years of Thatcherism and designer socialism, that the prospect of revolutionary change is more remote than ever. Indeed in the Cold War period the very petrified state of geo-politics actually allowed the projection of total social revolution - a real leap beyond capitalism in its Eastern and Western varieties - as the only possibility beyond the status quo. Now, however, we see the real dangers of fundamental changes and ruptures within the parameters of continuing capitalist development. Within these dangers there does lie the real possibility of the further development of the social revolutionary project. But to recognise and seize the opportunities the changing situation offers we need to arm ourselves theoretically and practically. The theoretical side of this requires a preservation and superseding of the revolutionary theory that has preceded us.

Capitalism creates its own negation in the proletariat, but the success of the proletariat in abolishing itself and capital requires theory. At the time of the first world war the theory and praxis of the classical workers' movement came close to smashing the capital relation. But it was defeated by capital using both Stalinism and social democracy. The domination of the workers movement by Stalinism and social democracy that followed was an expression of this defeat of both the theory and practice of the proletariat.

The first stirrings from the long slumber began in the fifties following the death of Stalin and with the revolts against Stalinism by East German and Hungarian workers. This rediscovery of autonomous practice by the proletariat was accompanied by a rediscovery of the high points of the theory of the classical workers movement. In particular the German and Italian left communist critiques of the Soviet Marxism, the seminal work of Lukacs and Korsch in the critique of the objectivism of Second International Marxism which Leninism has failed to go beyond.

The New Left that emerged from this process was in a sense the reemergence of a whole series of theoretical currents - council communism, class struggle and liberal versions of anarchism, Trotskyism - that had largely been submerged by Stalinism. But while a number of groups that sprung up to a large extent just regurgitated as ideology the theories they were discovering, there were some real attempts to go beyond these positions, to actually develop theory adequate to the modern conditions. The period is marked by an explosion of new ideas and possibilities. The situationists and the autonomists represent high points in this process of reflecting and expressing the needs of the movement.

The rediscovery of the proletariat's theory happened in a symbiotic relation with the rediscovery of proletarian revolutionary practice. The wildcat strikes and general refusal of work, the near revolution in France in '68, the 'counter cultural' creation of new needs by the proletariat, in total a successful attack on the Keynesian settlement that had maintained social peace since the war. But with capital's successful use of crisis to undermine the gains of the proletarian offensive began a crisis in the ideas of the movement. The crisis was a result of the attacks on practice. We can see a number of directions in the collapse of the New Left.

One was a reformist turn: Under the mistaken notion that they were taking the struggles further - marching through the institutions - many comrades entered the Western social democratic parties. This move did not act to unify and organise the mass movements and grassroots struggles but rather encouraged and covered up the decline of these social movements. Those who avoided the mistake of being incorporated into the system fell into twin errors. On the one hand many embroiled themselves in frantic party-building. They were persuaded that the problem with the movement so far was the lack of an organisation to attack capital and the state. While they built their party the movementwas breaking up. They were blind to the history of Trotskyism as the 'loyal opposition' to Stalinism.

On the other hand many of those who recognised the bankruptcy of Leninism fell into a libertarian swamp of lifestylism and total absorption in 'identity politics' etc. Meanwhile from Academia came a sophisticated attack on radical theory in the guise of radical theory. The libertarian critique of Leninism - that it is an attempt to replace one set of rulers with another set - was transformed into an attack on the very project of social revolution. While appearing in their discourse to be exceptionally radical, the political implications of the postmodernists and poststructuralists amount to at best a wet liberalism, while at worst a justification for nationalism and wars.

The collapse of the new left parallelled the retreat of the proletariat as a whole before the onslaught of capitalist restructuring. In Britain we had the debilitating affect of the 'social contract' under Labour and the exceptionally important defeat of the miners strike. Elsewhere the crushing of the Italian movement and so on.

This brings us to the present situation. The connection between the movement and ideas has been undermined. Theory and practice are split. Those who think do not act, and those who act do not think. In the universities where student struggles forced the opening of space for radical thought that space is under attack. The few decent academic Marxists are besieged in their ivory tower by the poststructuralist shock troops of neo-liberalism. Although decent work has been done in areas such as the state derivation debate there has been no real attempt apply any insights in the real world. Meanwhile out in the woods of practical politics, though we have had some notable victories recently, ideas are lacking. Many comrades, especially in Britain, are afflicted with a virulent anti-intellectualism that creates the ludicrous impression that the Trots are the ones with a grasp of theory. Others pass off conspiracy theories as a substitute for serious analysis.

We publish this journal as a contribution to the reuniting of theory and practice. Aufheben is a space for critical investigation which has the practical purpose of overthrowing capitalist society.

Comments

Distorted by the bourgeois press, reduced to a mere 'race riot' by many on the left, the L.A. rebellion was the most serious urban uprising this century. This article seeks to grasp the full significance of these events by relating them to their context of class re-composition and capitalist restructuring.

April 29th, 1992, Los Angeles exploded in the most serious urban uprising in America this century. It took the federal army, the national guard and police from throughout the country five days to restore order, by which time residents of L.A. had appropriated millions of dollars worth of goods and destroyed a billion dollars of capitalist property. Most readers will be familiar with many of the details of the rebellion. This article will attempt to make sense of the uprising by putting the events into the context of the present state of class relations in Los Angeles and America in order to see where this new militancy in the class struggle may lead.

Before the rebellion, there were two basic attitudes on the state of class struggle in America. The pessimistic view is that the American working class has been decisively defeated. This view has held that the U.S. is - in terms of the topography of the global class struggle - little more than a desert. The more optimistic view held, that despite the weakness of the traditional working class against the massive cuts in wages, what we see in the domination of the American left by single issue campaigns and "Politically Correct" discourse is actually evidence of the vitality of the autonomous struggles of sections of the working class. The explosion of class struggle in L.A. shows the need to go beyond these one-sided views.

Contents:

1. Beyond the Image

2. Race and Class Composition

3. Class Composition And Capitalist Restructuring

4. A Note on Architecture and the Postmodernists

5. Gangs

6. The Political Ideas of the Gangs

7. Conclusion

---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

1. Beyond the Image

As most of our information about the rioting has come through the capitalist media, it is necessary to deal with the distorted perspective it has given. Just as in the Gulf War, the media presented an appearance of full immersion in what happened while actually constructing a falsified view of the events. While in the Gulf there was a concrete effort to disinform, in L.A. the distortion was a product not so much of censorship as much as of the total incomprehension of the bourgeois media when faced with proletarian insurrection. As Mike Davis points out, most reporters, "merely lip-synched suburban cliches as they tramped through the ruins of lives they had no desire to understand. A violent kaleidoscope of bewildering complexity was flattened into a single, categorical scenario: legitimate black anger over the King decision hijacked by hard-core street criminals and transformed into a maddened assault on their own community." Such a picture is far from the truth.

The beating of Rodney King in 1991 was no isolated incident and, but for the chance filming of the event, would have passed unnoticed into the pattern of racist police repression of the inner cities that characterizes the present form of capitalist domination in America. But, because of the insertion of this everyday event into general public awareness the incident became emblematic. While the mainstream television audience forgot the event through the interminable court proceedings, the eyes of the residents of South Central L.A. and other inner cities remained fixed on a case that had become a focus for their anger towards the system King's beating was typical of. Across the country, but especially in L.A., there was the feeling and preparation that, whatever the result of the trial, the authorities were going to experience people's anger. For the residents of South Central, the King incident was just a trigger. They ignored his televised appeals for an end to the uprising because it wasn't about him. The rebellion was against the constant racism on the streets and about the systematic oppression of the inner cities; it was against the everyday reality of racist American capitalism.

One of the media's set responses to similar situations has been to label them as "race riots". Such a compartmentalisation broke down very quickly in L.A. as indicated in Newsweek's reports of the rebellion: "Instead of enraged young black men shouting `Kill Whitey', Hispanics and even some whites - men, women and children - mingled with African-Americans. The mob's primary lust appeared to be for property, not blood. In a fiesta mood, looters grabbed for expensive consumer goods that had suddenly become `free'. Better-off black as well as white and Asian-American business people all got burned." Newsweek turned to an "expert" - an urban sociologist - who told them, "This wasn't a race riot. It was a class riot." (Newsweek, May 11th, 1992).

Perhaps uncomfortable with this analysis they turned to "Richard Cunningham, 19", "a clerk with a neat goatee": "They don't care for anything. Right now they're just on a spree. They want to live the lifestyle they see people on TV living. They see people with big old houses, nice cars, all the stereo equipment they want, and now that it's free, they're gonna get it." As the sociologist told them - a class riot.

In L.A., Hispanics, blacks and some whites united against the police; the composition of the riot reflected the composition of the area. Of the first 5,000 arrests, 52 per cent were poor Latinos, 10 per cent whites and only 38 per cent blacks.

Faced with such facts, the media found it impossible to make the label "race riot" stick. They were more successful, however, in presenting what happened as random violence and as a senseless attack by people on their own community. It is not that there was no pattern to the violence, it is that the media did not like the pattern it took. Common targets were journalists and photographers, including black and Hispanic ones. Why should the rioters target the media? - 1) these scavengers gathering around the story offer a real danger of identifying participants by their photos and reports. 2) The uncomprehending deluge of coverage of the rebellion follows years of total neglect of the people of South Central except their representation as criminals and drug addicts. In South Central, reporters are now being called "image looters".

But the three fundamental aspects to the rebellion were the refusal of representation, direct appropriation of wealth and attacks on property; the participants went about all three thoroughly.

Refusal of Representation

While the rebellion in '65 had been limited to the Watts district, in '92 the rioters circulated their struggle very effectively. Their first task was to bypass their "representatives". The black leadership - from local government politicians through church organizations and civil rights bureaucracy - failed in its task of controlling its community. Elsewhere in the States this strata did to a large extent succeed in channelling people's anger away from the direct action of L.A., managing to stop the spread of the rebellion. The struggle was circulated, but we can only imagine the crisis that would have ensued if the actions in other cities had reached L.A.'s intensity. Still, in L.A. both the self-appointed and elected representatives were by-passed. They cannot deliver. The rioters showed the same disrespect for their "leaders" as did their Watts counterparts. Years of advancement by a section of blacks, their intersection of themselves as mediators between "their" community and US capital and state, was shown as irrelevant. While community leaders tried to restrain the residents, "gang leaders brandishing pipes, sticks and baseball bats whipped up hotheads, urging them not to trash their own neighborhoods but to attack the richer turf to the west".

"It was too dangerous for the police to go on to the streets" (Observer, May 3rd 1992).

Attacks on Property

The insurgents used portable phones to monitor the police. The freeways that have done so much to divide the communities of L.A. were used by the insurgents to spread their struggle. Cars of blacks and Hispanics moved throughout a large part of the city burning their targets - commercial premises, the sites of capitalist exploitation - while at other points traffic jams formed outside malls as their contents were liberated. As well as being the first multiethnic riot in American history, it was its first car-borne riot. The police were totally overwhelmed by the creativity and ingenuity of the rioters.

Direct Appropriations

"Looting, which instantly destroys the commodity as such, also discloses what the commodity ultimately implies: The army, the police and the other specialized detachments of the state's monopoly of armed violence."

Once the rioters had got the police off the streets looting was clearly an overwhelming aspect of the insurrection. The rebellion in Los Angeles was an explosion of anger against capitalism but also an eruption of what could take its place: creativity, initiative, joy.

A middle-aged woman said: "Stealing is a sin, but this is more like a television gameshow where everyone in the audience gets to win." Davis article in The Nation, June 1st.

"Looters of all races owned the streets, storefronts and malls. Blond kids loaded their Volkswagon with stereo gear... Filipinos in a banged up old clunker stocked up on baseball mitts and sneakers. Hispanic mothers with children browsed the gaping chain drug marts and clothing stores. A few Asians were spotted as well. Where the looting at Watts had been desperate, angry, mean, the mood this time was closer to a maniac fiesta".

The direct appropriation of wealth (pejoratively labelled "looting") breaks the circuit of capital (Work-Wage-Consumption) and such a struggle is just as unacceptable to capital as a strike. However it is also true that, for a large section of the L.A. working class, rebellion at the level of production is impossible. From the constant awareness of a "good life" out of reach - commodities they cannot have - to the contradiction of the simplest commodity, the use-values they need are all stamped with a price tag; they experience the contradictions of capital not at the level of alienated production but at the level of alienated consumption, not at the level of labor but at the level of the commodity.

"A lot of people feel that it's reparations. It's what already belongs to us." Will M., former gang member, on the "looting". (International Herald Tribune May 8th)

It is important to grasp the importance of direct appropriation, especially for subjects such as those in L.A. who are relatively marginalized from production. This "involves an ability to understand working-class behavior as tending to bring about, in opposition to the law of value, a direct relationship with the social wealth that is produced. Capitalist development itself, having reached this level of class struggle, destroys the `objective' parameters of social exchange. The proletariat can thus only recompose itself, within this level, through a material will to reappropriate to itself in real terms the relation to social wealth that capital has formally redimensioned".

[...]

2. Race and Class Composition

So even Newsweek, a voice of the American bourgeoisie, conceded that what happened was not a "race riot" but a "class riot". But in identifying the events as a class rebellion we do not have to deny they had "racial" elements. The overwhelming importance of the riots was the extent to which the racial divisions in the American working class were transcended in the act of rebellion; but it would be ludicrous to say that race was absent as an issue. There were "racial" incidents: what we need to do is see how these elements are an expression of the underlying class conflict. Some of the crowd who initiated the rebellion at the Normandie and Florence intersection went on to attack a white truck driver, Reginald Oliver Denny. The media latched on to the beating, transmitting it live to confirm suburban white fear of urban blacks. But how representative was this incident? An analysis of the deaths during the uprising shows it was not.

Still, we need to see how the class war is articulated in "racial" ways.

In America generally, the ruling class has always promoted and manipulated racism, from the genocide of native Americans, through slavery, to the continuing use of ethnicity to divide the labor force. The black working class experience is to a large extent that of being pushed out of occupations by succeeding waves of immigrants. While most groups in American society on arrival at the bottom of the labor market gradually move up, blacks have constantly been leapfrogged. Moreover, the racism this involves has been a damper on the development of class consciousness on the part of white workers.

In L.A. specifically, the inhabitants of South Central constitute some of the most excluded sectors of the working class. Capital's strategy with regards these sectors is one of repression carried out by the police - a class issue. However the Los Angeles Police Department (LAPD) is predominantly white and its victims massively black and Hispanic (or as P.C. discourse would have it, people of color). Unlike in other cities, where the racist nature of the split between the included and excluded sectors is blurred by the state's success in co-opting large numbers of blacks on to the police force, in L.A. capital's racist strategy of division and containment is revealed in every encounter between the LAPD and the population - a race issue.

When the blacks and Hispanics of L.A. have been marginalized and oppressed according to their skin color, it is not surprising that in their explosion of class anger against their oppressors they will use skin color as a racial shorthand in identifying the enemy, just as it has been used against them. So even if the uprising had been a "race riot", it would still have been a class riot. It is also important to recognize the extent to which the participants went beyond racial stereotypes. While the attacks on the police, the acts of appropriation and attacks on property were seen as proper and necessary by nearly everyone involved, there is evidence that acts of violence against individuals on the basis of their skin color were neither typical of the rebellion nor widely supported. In the context of the racist nature of L.A. class oppression, it would have been surprising if there had not been a racial element to some of the rebellion. What is surprising and gratifying is the overwhelming extent to which this was not the case, the extent to which the insurgents by-passed capital's racist strategies of control.

"A lot of people feel that in order to come together we have to sacrifice the neighborhood." Will M., former gang member, on the destruction of businesses. (International Herald Tribune May 8th, 1992.)

One form the rebellion took was a systematic assault on Korean businesses. The Koreans are on the front-line of the confrontation between capital and the residents of central L.A. - they are the face of capital for these communities. Relations between the black community and the Koreans had collapsed following the Harlins incident and its judicial result. In an argument over a $1.79 bottle of orange juice, Latasha Harlins, a 15-year old black girl, was shot in the back of the head by a Korean grocer - Soon Ja Du - who was then let off with a $500 fine and some community service. While the American State packs its Gulags with poor blacks for just trying to survive, it allows a shopkeeper to kill their children. But though this event had a strong effect on the blacks of South Central, their attack on Korean property cannot be reduced to vengeance for one incident - it was directed against the whole system of exchange. The uprising attacked capital in its form of property, not any property but the property of businesses - the institutions of exploitation; and in the black and Hispanic areas, most of these properties and businesses were owned by Koreans. But though we should understand the resentment towards the Koreans as class-based, it is necessary to put this in the context of the overall situation. In L.A., the black working-class's position deteriorated in the late 1970s with the closure of heavy industry, whereas at the end of the 60s they had started to be employed in large numbers. This was part of the internationalization of L.A.'s economy, its insertion into the Pacific Rim center of accumulation which also involved an influx of mainly Japanese capital into downtown redevelopment, immigration of over a million Latin Americans to take the new low-wage manufacturing jobs that replaced the jobs blacks had been employed in, and the influx of South Koreans into L.A.'s mercantile economy. Thus while Latinos offered competition for jobs, the Koreans came to represent capital to blacks. However, these racial divisions are totally contingent. Within the overall restructuring, the jobs removed from L.A. blacks were relocated to other parts of the Pacific Rim such as South Korea. The combativity of these South Korean workers shows that the petty-bourgeois role Koreans take in L.A. is but part of a wider picture in which class conflict crosses all national and ethnic divides as global finance capital dances around trying to escape its nemesis but always recreating it.

3. Class Composition and Capitalist Restructuring

The American working class is divided between waged and unwaged, blue and white collar, immigrant and citizen labor, guaranteed and unguaranteed; but as well as this, and often synonymous with these distinctions, it is divided along ethnic lines. Moreover, these divisions are real divisions in terms of power and expectations. We cannot just cover them up with a call for class unity or fatalistically believe that, until the class is united behind a Leninist party or other such vanguard, it will not be able to take on capital. In terms of the American situation as well as with other areas of the global class conflict it is necessary to use the dynamic notion of class composition rather than a static notion of social classes.

"When Bush visited the area security was massive. TV networks were asked not to broadcast any of Mr Bush's visit live to keep from giving away his exact location in the area." (International Herald Tribune, May 8th, 1992.)

The rebellion in South Central Los Angeles and the associated actions across the United States showed the presence of an antagonistic proletarian subject within American capitalism. This presence had been occluded by a double process: on the one hand, a sizeable section of American workers have had their consciousness of being proletarian - of being in antagonism to capital - obscured in a widespread identification with the idea of being "middle-class"; and on the other, for a sizeable minority, perhaps a quarter of the population, there has being their recomposition as marginalized sub-workers excluded from consideration as a part of society by the label "underclass". The material basis for such sociological categorizations is that, on the one hand there is the increased access to "luxury" consumption for certain "higher" strata, while on the other there is the exclusion from anything but "subsistence" consumption by those "lower" strata consigned to unemployment or badly paid part-time or irregular work.

This strategy of capital's carries risks, for while the included sector is generally kept in line by the brute force of economic relations, redoubled by the fear of falling into the excluded sector, the excluded themselves, for whom the American dream has been revealed as a nightmare, must be kept down by sheer police repression. In this repression, the war on drugs has acted as a cover for measures that increasingly contradict the "civil rights" which bourgeois society, especially in America, has prided itself on bringing into the world.

Part of the U.S. capital's response to the Watts and other 60s rebellions was to give ground. To a large section of the working class revolting because its needs were not being met, capital responded with money - the form of mediation par excellence - trying to meet some of that pressure within the limits of capitalist control. This was not maintained into the 80s. For example, federal aid to cities fell from $47.2 billion in 1980 to $21.7 billion in 1992. The pattern is that of the global response to the proletarian offensives of the 60s and 70s: first give way - allowing wage increases, increasing welfare spending (i.e. meeting the social needs of the proletariat) - then, when capital has consolidated its forces, the second part - restructure accumulation on a different basis - destructure knots of working class militancy, create unemployment.

In America, this strategy was on the surface more successful than in Europe. The American bourgeoisie had managed to halt the general rise in wages by selectively allowing some sectors of the working class to maintain or increase their living standards while others had their's massively reduced. One sector in particular has felt the brunt of this strategy: the residents of the inner city who are largely black and Hispanic. The average yearly income of black high school graduates fell by 44% between 1973 and 1990, there have been severe cutbacks in social programs and massive disinvestment. With the uprising, the American working class has shown that capital's success in isolating and screwing this section has been temporary.

The re-emergence of an active proletarian subject shows the importance, when considering the strategies of capital, of not forgetting that its restructuring is a response to working class power. The working class is not just an object within capital's process. It is a subject (or plurality of subjects), and, at the level of political class composition reached by the proletariat in the 60s, it undermined the process. Capital's restructuring was an attack on this class composition, an attempt to transform the subject back into an object, into labor-power.

Capitalist restructuring tried to introduce fragmentation and hierarchy into a class subject which was tending towards unity (a unity that respected multilaterality). It moved production to other parts of the world (only, as in Korea, to export class struggle as well); it tried to break the strength of the "mass worker" by breaking up the labor force within factories into teams and by spreading the factory to lots of small enterprises; it has also turned many wage-laborers into self-employed to make people internalise capital's dictates. In America, the fragmentation also occurred along the lines of ethnicity. Black blue-collar workers have been a driving force in working class militancy as recorded by C.L.R. James and others. For a large number of blacks and others, the new plan involved their relegation to Third World poverty levels. But as Negri puts it, "marginalization is as far as capital can go in excluding people from the circuits of production - expulsion is impossible. Isolation within the circuit of production - this is the most that capital's action of restructuration can hope to achieve." When recognizing the power of capital's restructuring it is necessary to affirm the fundamental place of working class struggles as the motor force of capital's development. Capital attacks a certain level of political class composition and a new level is recomposed; but this is not the creation of the perfect, pliable working class - it is only ever a provisional recomposition of the class on the basis of its previously attained level.

Capitalist restructuring has taken the form in Los Angeles of its insertion into the Pacific Rim pole of accumulation. Metal banging and transport industry jobs, which blacks only started moving into in the tail end of the boom in late 60s and the early 70s, have left the city, while about one million Latino immigrants have arrived, taking jobs in low-wage manufacturing and labor-intensive services. The effect on the Los Angeles black community has not been homogeneous; while a sizeable section has attained guaranteed status through white-collar jobs in the public sector, the majority who were employed in the private sector in traditional working class jobs have become unemployed. It is working class youth who have fared worse, with unemployment rates of 45% in South Central.

But the recomposition of the L.A. working class has not been entirely a victory of capitalist restructuring. Capital would like this section of society to work. It would like its progressive undermining of the welfare system to make the "underclass" go and search for jobs, any jobs anywhere. Instead, many residents survive by "Aid to Families With Dependent Children", forcing the cost of reproducing labor power on to the state, which is particularly irksome when the labor power produced is so unruly. The present consensus among bourgeois commentators is that the problem is the "decline of the family and its values." Capital's imperative is to re-impose its model of the family as a model of work discipline and form of reproduction (make the proles take on the cost of reproduction themselves).

4. A Note on Architecture and the Postmodernist

Los Angeles, as we know, is the "city of the future". In the 30s the progressive vision of business interests prevailed and the L.A. streetcars - one of the best public transport systems in America - were ripped up; freeways followed. It was in Los Angeles that Adorno & Horkheimer first painted their melancholy picture of consciousness subsumed by capitalism and where Marcuse later pronounced man "One Dimensional". More recently, Los Angeles has been the inspiration for fashionable post-theory. Baudrillard, Derrida and other postmodernist, post-structuralist scum have all visited and performed in the city. Baudrillard even found here "utopia achieved".

The "postmodern" celebrators of capitalism love the architecture of Los Angeles, its endless freeways and the redeveloped downtown. They write eulogies to the sublime space within the $200 a night Bonaventura hotel, but miss the destruction of public space outside. The postmodernists, though happy to extend a term from architecture to the whole of society, and even the epoch, are reluctant to extend their analysis of the architecture just an inch beneath the surface. The "postmodern" buildings of Los Angeles have been built with an influx of mainly Japanese capital into the city. Downtown L.A. is now second only to Tokyo as a financial center for the Pacific Rim. But the redevelopment has been at the expense of the residents of the inner city. Tom Bradley, an ex-cop and Mayor since 1975, has been a perfect black figurehead for capital's restructuring of L.A.. He has supported the massive redevelopment of downtown L.A., which has been exclusively for the benefit of business. In 1987, at the request of the Central City East Association of Businesses, he ordered the destruction of the makeshift pavement camps of the homeless; there are an estimated 50,000 homeless in L.A., 10,000 of them children. Elsewhere, city planning has involved the destruction of people's homes and of working class work opportunities to make way for business development funded by Pacific Rim capital - a siege by international capital of working class Los Angeles.

But the postmodernists did not even have to look at this behind-the-scenes movement, for the violent nature of the development is apparent from a look at the constructions themselves. The architecture of Los Angeles is characterised by militarization. City planning in Los Angeles is essentially a matter for the police. An overwhelming feature of the L.A. environment is the presence of security barriers, surveillance technology - the policing of space. Buildings in public use like the inner city malls and a public library are built like fortresses, surrounded by giant security walls and dotted with surveillance cameras.

In Los Angeles, "on the bad edge of postmodernity, one observes an unprecedented tendency to merge urban design, architecture and the police apparatus in a single comprehensive security effort." (Davis, City of Quartz p. 224) Just as Haussman redesigned Paris after the revolutions of 1848, building boulevards to give clear lines of fire, L.A. architects and city planners have remade L.A. since the Watts rebellion. Public space is closed, the attempt is made to kill the street as a means of killing the crowd. Such a strategy is not unique to Los Angeles, but here it has reached absurd levels: the police are so desperate to "kill the crowd" that they have taken the unprecedented step of killing the toilet. Around office developments "public" art buildings and landscaped garden "microparks" are designed into the parking structures to allow office workers to move from car to office or shop without being exposed to the dangers of the street. The public spaces that remain are militarized, from "bum-proof" bus shelter benches to automatic sprinklers in the parks to stop people sleeping there. White middle class areas are surrounded by walls and private security. During the riots, the residents of these enclaves either fled or armed themselves and nervously waited.

We see, then, that in the States, but especially in L.A., architecture is not merely a question of aesthetics, it is used along with the police to separate the included and the excluded sections of capitalist society. But this phenomenon is by no means unique to America. Across the advanced capitalist countries we see attempts to redevelop away urban areas that have been sites of contestation. In Paris, for example, we have seen, under the flag of "culture", the Pompidou centre built on a old working class area, as a celebration of the defeat of the '68 movement. Here in Britain the whole of Docklands was taken over by a private development corporation to redevelop the area - for a while yuppie flats sprang up at ridiculous prices and the long-standing residents felt besieged in their estates by armies of private security guards. Still, we saw how that ended... Now in Germany, the urban areas previously marginalized by the Wall, such as Kreuzberg and the Potzdamer Platz, have become battlegrounds over who's needs the new Berlin will satisfy.

Of course, such observations and criticisms of the "bad edge of postmodernity", if they fail to see the antagonism to the process and allow themselves to be captivated by capital's dialectic, by its creation of our dystopia, could fall into mirroring the postmodernists' celebration of it. There is no need for pessimism - what the rebellion showed was that capital has not killed the crowd. Space is still contested. Just as Haussman's plans did not stop the Paris Commune, L.A. redevelopment did not stop the 1992 rebellion.

5. Gangs

"In June 1988 the police easily won Police Commission approval for the issuing of flesh-ripping hollow-point ammunition: precisely the same `dum-dum' bullets banned in warfare by the Geneva Conventions." (Mike Davis, 1990, City of Quartz, p. 290.)

We cannot deny the role gangs played in the uprising. The systematic nature of the rioting is directly linked to their participation and most importantly to the truce on internal fighting they called before the uprising. Gang members often took the lead which the rest of the proletariat followed. The militancy of the gangs - their hatred of the police - flows from the unprecedented repression the youth of South Central have experienced: a level of state repression on a par with that dished out to rebellious natives by colonial forces such as that suffered by Palestinians in the Occupied Territories. Under the guise of gang-busting and dealing with the "crack menace", the LAPD have launched massive "swamp" operations; they have formed files on much of the youth of South Central and murdered lots of proletarians.

As Mike Davis put it in 1988, "the contemporary Gang scare has become an imaginary class relationship, a terrain of pseudo-knowledge and fantasy projection, a talisman." The "gang threat" has been used as an excuse to criminalise the youth of South Central L.A. We should not deny the existence of the problems of crack use and inter-gang violence, but we need to see that, what has actually been a massive case of working class on working class violence, a sorry example of internalised aggression resulting from a position of frustrated needs, has been interpreted as a "lawless threat" to justify more of the repression and oppression that created the situation in the first place. To understand recent gang warfare and the role of gangs in the rebellion we must look at the history of the gang phenomenon.

In Los Angeles, black street gangs emerged in the late 1940s primarily as a response to white racist attacks in schools and on the streets. When Nation of Islam and other black nationalist groups formed in the late 50s, Chief Parker of the LAPD conflated the two phenomena as a combined black menace. It was a self-fulfilling prophecy, for the repression launched against the gangs and black militants had the effect of radicalizing the gangs. This politicization reached a peak in the Watts rebellion, when, as in '92, gang members made a truce and were instrumental in the black working class success in holding off the police for four days. The truce formed in the heat of the rebellion lasted for most of the rest of the 60s. Many gang members joined the Black Panther Party or formed other radical political groupings. There was a general feeling that the gangs had "joined the Revolution".

The repression of the movement involved the FBI's COINTELPRO program and the LAPD's own red squad. The Panthers were shot on the streets and on the campuses both directly by the police and by their agents, their headquarters in L.A. were besieged by LAPD SWAT teams, and dissension was sown in their ranks. Although the Panthers' politics were flawed, they were an organic expression of the black proletariat's experience of American capitalism. The systematic nature of their repression shows just how dangerous they were perceived to be.